In August 1861, a couple of weeks after the Union’s disastrous defeat at Bull Run, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase traveled from Washington to New York in search of money. Bull Run had destroyed hopes of a swift end to the fighting, and the war was already costing more than $1 million per day. (The federal government’s total annual expenditure during the 1850s had averaged less than $60 million.) Chase had come to see the representatives of the Associated Banks, the nation’s leading financiers, who were attentive to the perils of the moment. They agreed to his request for an immediate $50 million, with the possibility of another $100 million in due course. But they couldn’t approve the secretary’s demand that this gigantic sum be paid in gold. Didn’t Chase understand that a bank simply couldn’t empty its vaults and remain in business?

Chase didn’t like bankers and didn’t know a lot about banking: he’d been a lawyer and an antislavery campaigner in Ohio before winning a US Senate seat in 1849. (Chase Bank was named in his honor four years after his death, but he had no connection with the firm.) Chase had tried and failed to win the Republican presidential nomination in the summer of 1860; the following January he accepted Lincoln’s offer of a cabinet post, but he could never shake the feeling that he would be better suited to the White House than the Treasury. Chase’s confidence and self-regard assumed their full stature when the bankers pushed back against his demand for gold. If the Associated Banks refused his terms, he declared, “I will go back to Washington, and issue notes for circulation; for it is certain that the war must go on until the rebellion is put down, if we have to put out paper until it takes a thousand dollars to buy a breakfast.”

The relationship between government and money has changed so fundamentally since the summer of 1861 that the contemporary version of this meeting would be quite different. Today’s treasury secretary would likely have direct experience of banking before taking office. In a modern financial crisis, the government would probably be bailing the banks out rather than vice versa. A twenty-first-century secretary would come to the meeting wielding the mighty dollar, a fiat currency backed by the confidence of investors within and beyond the United States rather than by gold. And they would be able to draw on the powers of the Federal Reserve, created in 1913, which can conjure money into being on an epic scale—most recently during the great crash of 2007–2008 and the Covid shutdown of 2020. In short, the idea of a government official approaching a banker and asking for gold—then making threats about $1,000 breakfasts—seems fantastically quaint given the complexity and muscle of the modern US financial system.

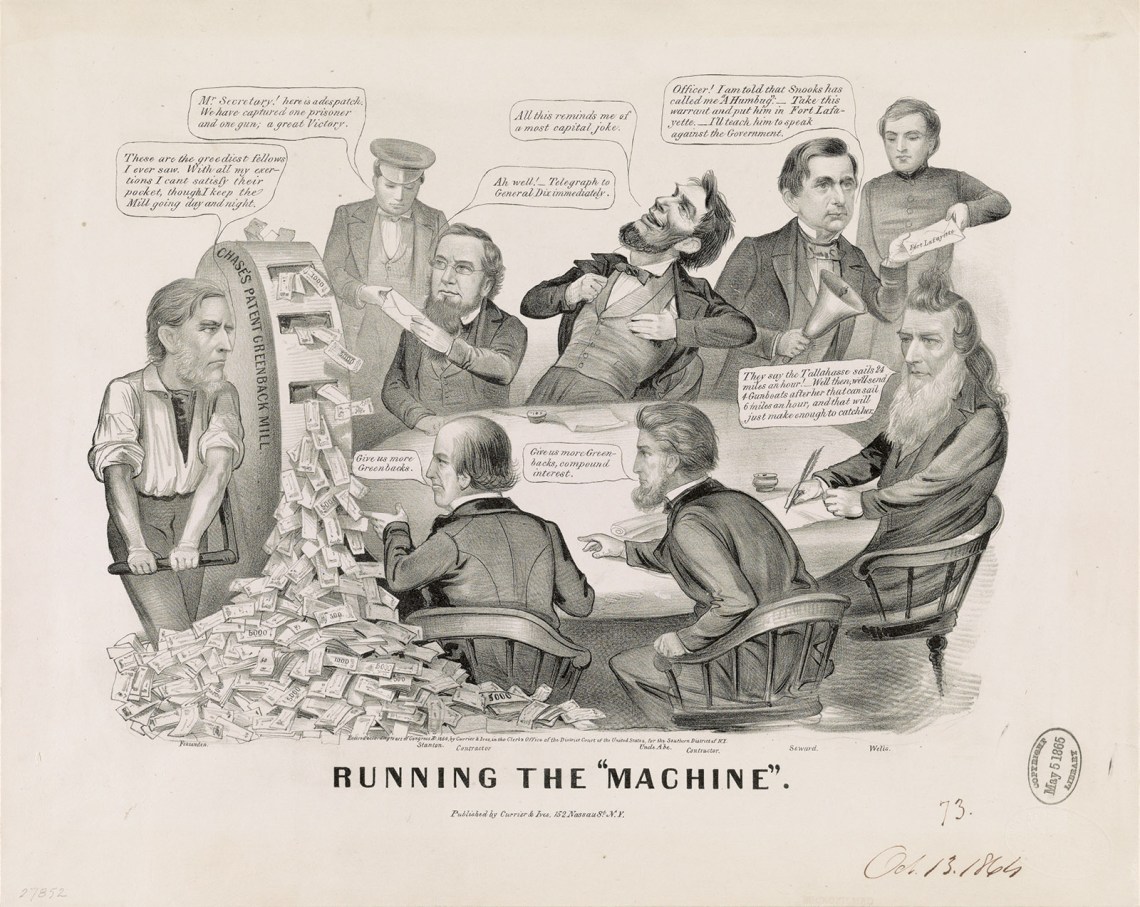

Roger Lowenstein’s Ways and Means and David K. Thomson’s Bonds of War remind us that the Civil War energized the nation’s transformation from a modest and decentralized economic actor into the global juggernaut of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. During the war years, banks were reorganized as national rather than state institutions, Congress introduced the first federal income tax, billions of dollars of government bonds were sold to an unprecedentedly diverse range of buyers, and the Treasury printed $450 million of “greenbacks”—the first paper currency issued by the American government since the Revolution.

These innovations undoubtedly helped the United States win the Civil War, but did they increase economic opportunity? One of the many ironies of nineteenth-century history is that the Republicans who saved the Union and destroyed slavery in the 1860s oversaw some of the biggest financial scandals of the following decades. They also ran interference for corporate and financial interests that tyrannized labor before the century was out. Both books grapple with the question of whether this unedifying outcome was a betrayal of the Civil War years or a consequence of the tools and precedents that the war had supplied to America’s political and financial elites.

From the earliest moments of the republic, political elites argued about the extent of the government’s involvement in the economy. During the 1790s Alexander Hamilton championed an interventionist approach that would settle Revolutionary War debts, assist nascent industries and businesses, and establish a national bank along the lines of the Bank of England. Hamilton’s detractors—including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison—warned that his prescriptions would concentrate economic power and squander the republic’s greatest advantage over Europe: its vast reserve of western land, with the potential to support industrious farmers rather than an industrial proletariat.

As these arguments played out from the 1790s to the Civil War, a few trends became apparent. A Bank of the United States was chartered for twenty years in 1791 and again in 1816, but its supporters struggled on each occasion to persuade Jeffersonians (and, later, Jacksonians) that it was truly working in the nation’s interest. Andrew Jackson waged war on the Second Bank in the 1830s, insisting that it served its private stockholders (who supplied more than four fifths of its capital) rather than the humble American farmer. After Jackson vetoed the renewal of its charter, the bank downsized its operations and became a state-chartered institution (under the ungainly name of the Bank of the United States of Pennsylvania) before going bankrupt in 1841.

Advertisement

States had been issuing bank charters since the 1780s, and by 1820 more than three hundred private banks had been established across the nation. These banks issued notes against their reserves, and those notes circulated widely. During its years of operation, the Bank of the United States attempted to monitor and regulate these institutions, principally by requiring any state banks that appeared to be running hot to redeem notes for specie. Not even a prudent and activist Bank of the United States could eliminate risk in this decentralized banking system. In ordinary commercial transactions, notes issued by state-chartered banks were discounted to reflect the uncertainty over whether their issuing bank was still in business. (The farther away from their place of origin, the higher the discount.) The dollar functioned as a national currency before the Civil War, but within a complex system of state-based private banks, light (if any) government oversight, and nerve-shredding latency.

The federal budget, funded by customs duties and land sales, remained relatively small before 1860. Hamilton’s vision of a government that could expand easily in a time of war had just about held up through the War of 1812, which the Jeffersonians fought on the cheap through privateers rather than an expanded military. The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) was a more expensive proposition, though the federal government easily sold bonds to defray the $70 million cost of military operations. In the first half of the 1850s, with the Treasury swollen by customs revenues and the mineral wealth of California, those bonds were gradually redeemed. Had it not been for the Panic of 1857, the United States might have entered the 1860s with no federal debt whatever.

In the event, the nation owed around $65 million at the time of Abraham Lincoln’s election—a sum roughly equivalent to one year’s federal expenditure. By the time the war was over, the United States would owe nearly $3 billion, and its annual expenditure would be close to half that sum. Lowenstein and Thomson cite the same, probably apocryphal, quote from a “Confederate leader” at the war’s end: “The Yankees did not whip us in the field. We were whipped in the Treasury Department.” Although this remark seems too good to be true, it’s difficult to dispute that the Union’s ability to mobilize money was crucial to defeating the South.

At first glance, the battle between the Confederacy and the United States looks extremely one-sided. The Union had nearly two and a half times the population of the Confederacy, three times the acreage in improved farmland, and four times the bank capital. The value of goods manufactured in New York alone was equivalent to four times the total across the entire Confederacy. The largest single concentration of wealth in the South was in human beings: Lowenstein estimates the value of the enslaved population at $2.7 billion in 1861. The threat to this wealth from Lincoln’s election motivated the formation of the Confederacy. But the South had two advantages. First, the Confederate government had access to cotton, which was hugely in demand in Europe and might underwrite loans and bond sales. Second, Confederate officials didn’t need to conquer the North, but simply to exhaust its resolve—or its finances.

The Confederacy did a poor job of leveraging its first advantage. Instead of shipping cotton to Europe quickly, Jefferson Davis’s government impounded the crop to pressure Britain and France into offering diplomatic recognition. This gave the US Navy time to plan a blockade of Southern ports. Things could have been very different. The Confederate politician Judah P. Benjamin told his fellow cabinet members in March 1861 that the South should simply buy and ship cotton en masse and stockpile it in Britain. It could then be sold gradually over the course of the war, giving the Confederacy a hedge against blockade or invasion. By the time Davis realized the necessity of cotton exports and abandoned his embargo, the noose envisaged by Benjamin had been tightly fixed around Confederate shipping.

The fiasco over cotton didn’t doom the South to defeat. Lowenstein acknowledges that the Confederate economy was perpetually dysfunctional: the government struggled to squeeze taxes and loans from a population in rebellion against a distant and purportedly oppressive authority, and with the Union blockade decimating tariff incomes, the Confederate Treasury was forced to print money. Salmon Chase’s $1,000 breakfast very nearly became a reality in the South. And yet the Confederacy was still able to market bonds (secured by the promise of cotton) to European investors well into 1864. British politicians like Viscount Palmerston and William Gladstone made speeches offering hope to beleaguered Confederates; The New York Times even accused Gladstone in 1865 of investing in Confederate bonds. Chase, meanwhile, struggled to press his advantage. There was plenty of money in the United States, but finding a way to channel it to the federal government was not simple. With the Union going nowhere on the battlefield by the end of 1861, and the war’s costs ballooning to $2 million a day in the first weeks of 1862, the pressure for some kind of compromise with the Confederacy began to build.

Advertisement

This was an exceptionally dangerous moment for the republic. As the Ohio senator John Sherman (who later became treasury secretary) recalled in his memoir, “It was apparent that a radical change in existing laws…must be made” or “the destruction of the Union would be unavoidable, notwithstanding the immense resources of the country which had then hardly been touched.” Chase and the congressional Republicans crafted three mechanisms for tapping into these immense resources, each radical both for the war effort and in the long arc of American economic history.

First, Congress passed the nation’s first federal income tax, which became larger and more progressive as the war went on. Second, it passed the Legal Tender Act, which allowed the federal government to print up to $150 million of notes without the promise that they would be redeemable against gold. For Chase—who in his younger days had sympathized with Andrew Jackson’s hostility toward banks and paper money—this was a hard pill to swallow. But these notes, which became known as greenbacks thanks to their distinctive color, were the forerunner of modern American currency. Greenbacks were printed in denominations as low as five dollars, which allowed the government to settle its debts to contractors and even individual soldiers. In turn, the notes circulated freely among Americans, who trusted that their government’s power might temporarily substitute for the security of gold or silver.

Third, the Treasury embarked on an unprecedented series of bond issues, hoping to persuade investors big and small, foreign and domestic, to bet on the future of the Union. These bonds eventually financed more than 60 percent of the North’s military expenses—well over $2 billion before the war’s end. But in 1862, with the Union’s military fortunes wavering, the bonds were hard to sell. In the final months of that year the federal government was once more running out of money, so Chase approached a little-known Philadelphia banker for help.

Jay Cooke was not a self-effacing man. “Like Moses and Washington and Lincoln and Grant,” he wrote in his 1894 memoir, “I have been—I firmly believe—God’s chosen instrument especially in the financial work of saving the Union.” Cooke became easily the most famous financier of the 1860s, and then the most infamous of the decade that followed. He’d become a banker in the 1840s—his father was a lawyer and US congressman—and made a modest fortune selling government bonds during the Mexican-American War. After the Panic of 1857, Cooke had had enough: he retired at the age of thirty-six, still holding a “fair fortune” despite the recent crash. He returned to banking in 1861, not from a sense of patriotism but to teach his son the trade. Cooke was a little different from the “money men” of New York. For one thing, he was based out of Philadelphia, which gave him some distance from the herd instincts of Wall Street. He was also a pioneer in the mass marketing of financial products. David Thomson’s Bonds of War gives us the fullest picture yet of his accomplishments.

Cooke began trading in Civil War bonds in 1861, as one of many investment bankers who bought government paper and resold it to individual investors. Chase had known Cooke’s brother—a newspaper editor in Ohio—before the war, but the banker and the treasury secretary forged a friendship only after the fighting had started. By 1862 they had become so close that Chase sent his daughters to stay with Cooke in Philadelphia during a smallpox outbreak in Washington. When Chase complained about the slow sale of bonds in the fall of that year, Cooke asked for the exclusive right to market the entire issue. Chase said yes, and over the next year Cooke sold more than half a billion dollars’ worth at a commission of 0.375 percent. Cooke’s boasts about being the Moses of the Union begin to make sense when set against these figures.

Lowenstein describes a “troubling informality” in the business conducted by Chase and Cooke, and before long their dealings came under scrutiny from politicians, media, and rival financiers. But Lowenstein and Thomson mostly focus on Cooke’s achievements in marketing government debt to an amazingly diverse array of people. Cooke managed this through a nationwide network of sales agents, an unprecedented advertising blitz, and a message of what Thomson calls “patriotic self-interest.” Cooke presented bonds as a way for ordinary Americans to participate in the war effort, offering denominations small enough to lure investors of modest means. The bonds, according to Cooke’s many promotional flyers, were equally appealing to “the surplus funds of capitalists, as well as the earnings of the industrial classes.”

Although the record of bond sales in the National Archives is incomplete, Thomson’s impressive research follows Cooke’s agents across the Union and even into the Confederacy as Lincoln’s armies began to claw back rebel territory. The wealthy were the biggest buyers, but they were not the only target for Cooke’s marketing drive: cobblers, boardinghouse keepers, soldiers, farmers, and laborers all feature in Thomson’s story. Women bought bonds in significant quantities. So did immigrants, with Cooke running German-language advertisements in several cities. By 1865 newspapers were reporting that the crowds in Cooke’s sales offices were composed “of all classes, and all degrees, and of all colors.” Clearly the everyman bondholder was not just a promotional wheeze.

Thomson also offers a fascinating snapshot of the European trade in American bonds. Historians (including Lowenstein) usually portray the Union’s effort to secure overseas investment as anemic. Lincoln dispatched a representative to London in the summer of 1861 to inquire discreetly about financing but was rebuffed. Meanwhile, the Confederacy succeeded in floating its own bonds in Paris, secured by cotton rather than gold. (As late as 1864, those bonds were, incredibly, trading closer to par in Europe than the Union’s bonds.) Thomson takes us to parts of Europe that historians have previously overlooked—Amsterdam and Frankfurt, especially—to uncover a lively secondary market in Union bonds. While his subtitle—“How Civil War Financial Agents Sold the World on the Union”—may overstate the case, Bonds of War reveals the Union cause as a much more attractive prospect to European investors than we have previously imagined.

The idea of an investment banker as the Civil War’s unsung hero may be hard to swallow. But before assessing Thomson’s claim that Jay Cooke “made the war a people’s contest,” it’s worth putting this historical moment into a broader setting.

Before 1861 government officials and bankers had routinely colluded to protect slavery, or even to use the proceeds of slave trading to secure the government’s finances. In the 1710s Britain transferred a huge portion of its national debt to the South Sea Company, which had acquired the lucrative right to trade enslaved people to Spanish America. A century later, the Second Bank of the United States helped drive the slavery boom in the emerging cotton belt. In the 1830s, when Britain finally abolished Caribbean slavery, its government borrowed £20 million to compensate planters for the loss of the human beings they had enslaved. This debt, to some of the wealthiest families in Britain, was paid off by British taxpayers only in 2015.

By contrast, the Civil War’s unprecedented financial mobilization had a radical directness: taxes, bonds, and greenbacks facilitated the destruction of slavery without compensation or compromise. The British approach to abolition had been to preserve enslavers’ wealth by expanding the national debt; the Union approach was to destroy that fictive $2.7 billion of white southern wealth and to liberate four million human beings who had been brutally commodified.

Lowenstein and Thomson make even wider claims for the economic radicalism of the Civil War. Republicans sincerely believed that the interests of labor and capital could be reconciled, insists Lowenstein, and that enlightened management of the economy could produce a prosperous and egalitarian society. Thomson presents Cooke’s bond issues as a sign not only of “patriotic self-interest” but of the emergence of the “everyday investor” in American economic life. The equation of Civil War bonds and a Robinhood account is one that Thomson wisely postpones until the final paragraph of his book, but at various moments he channels Cooke’s enthusiasm for the supposed democratization of the markets. Both authors are so upbeat about the 1860s that they are obliged to supply a final chapter in which the economic and social crises of the rest of the nineteenth century are briefly acknowledged. Karl Marx, who had closely followed the Civil War from London, offered a bracing assessment of its financial consequences in the first volume of Capital:

The American Civil War brought in its train a colossal national debt, and, with it, pressure of taxes, the rise of the vilest financial aristocracy, the squandering of a huge part of the public land on speculative companies for the exploitation of railways, mines, &c, in brief, the most rapid centralization of capital.

Marx’s disdain for the postwar trajectory of the American economy did not dent his admiration for Lincoln and the cause of the Union. He argued that the southern slave system had to be destroyed before the proletariat in Europe (dependent on slave-produced cotton) or in the northern states could overthrow capital. While the second phase of this plan did not materialize, Marx’s steadfast belief that the Civil War represented an economic revolution of global significance should not be dismissed.

The crowning achievement of the Republican Party, and of Lincoln and Chase in particular, was to bet everything on a war with the Confederacy without compromising on the need for abolition. But the Republicans’ broader economic ideology, and their faith in an underlying sympathy between labor and capital, fostered a politics of wishful thinking in the war’s aftermath. Republicans refused to transfer the enslavers’ vast landholdings to African Americans, who emerged from the war with nothing but freedom. The federal government declined to pump funds into the development of the postwar South, leaving Black sharecroppers subject to new regimes of economic and racial exploitation on the lands that had formerly anchored the slave system. Reconstruction, in W.E.B. Du Bois’s stinging phrase, left “a North hesitating between democracy with black voters and plutocracy with white supremacy.”

Even in the American West, the events of the postbellum era diverted from the Civil War script. Lowenstein rhapsodizes about the centrality of the West in Lincoln’s political imagination: it was to be the repository of future immigrants, the vast store of land to be worked by ordinary people, and the staging ground for railroads and other projects that would unite the nation. That the war years brought the passage of the Homestead Act and other federal legislation to inaugurate this vision was not a coincidence. Before secession, the West had been a battleground (literally) for northern and southern visions of the American future. After 1861, free of the drag of their southern antagonists, northern and western representatives in Congress pioneered the Republican developmental project. They were fully aware that this project was principally for white people: African Americans would stay in the South, or even leave the United States, and a prosperous West would depend on the extinguishment of indigenous rights and titles in the vast interior.

A brutal war for empire against Native Americans was waged during the Reconstruction years, but the Shangri-La of the trans-Mississippi West never quite materialized for working people. Many struggled to mobilize the capital needed to sustain their homestead claims; others, especially new immigrants, failed to escape the rapidly industrializing cities where they made landfall in the United States. The spectacular success of Cooke inspired a wave of corporate bond issues in the late 1860s and early 1870s, but the Republican Congress shelved the war’s other financial innovations. The progressive federal income tax, with its potential to raise revenue for investment and intervention, was swiftly abolished. New banking legislation, intended to bring state-chartered banks into a national system, included a surrender to New York, which allowed banks in the rest of the country to transfer their assets to Wall Street and supercharge speculative financial activity. Along with the speedy withdrawal of greenbacks, these measures helped dry up credit for middling and poorer Americans, especially in rural and western areas. Lincoln had centered farming and the West in his vision of American opportunity, but then the Republican Party became the party of big business, reviled by the agricultural classes it had previously idealized.

In her classic study The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies During the Civil War (1997), Heather Cox Richardson insisted that “the Republicans’ tragic weakness was not cupidity, but self-righteous optimism.” This may be overgenerous: as the financial scandals of the 1870s revealed, there was plenty of cupidity to accompany Republican naiveté. Cooke, along with hundreds of members of Congress, knew full well the opportunities for material advantage that the cozy relationship between business and politics now supplied. Cooke found himself at the center of one of the ensuing scandals, as his overinvestment in railroad bonds brought down his entire financial empire in 1873 (nearly capsizing the US economy in the process). The Civil War hadn’t begun as a war against slavery, but when it became one, the Republican leadership in the White House and Congress bet every dollar they could find on the promise of Union and emancipation. The sheer brilliance of this effort, morally and politically, made it easier for contemporaries to overlook the fact that the nation’s economic power could increase inequality at least as easily as it could secure freedom.