Are novelists required to like humans? It’s fair to say, on the evidence of her published writing, that Sara Baume is not a people person. Her first novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither (2015), tells the story of Ray, a self-proclaimed misfit who goes on the run in rural Ireland with One Eye, his adopted dog. Ray was bullied as a schoolboy—“I didn’t really believe I was of the same species” as other children, he says—and his father cruelly neglected him. Now, at fifty-seven, he finds a kindred spirit in hairy, malodorous One Eye, who is prone to aggression. Men step out of the way when Ray passes on the street. Supermarket cashiers take a bathroom break when they see him waiting in the queue. “When I drive past a children’s playground, some au-pair nearly always makes a mental note of my registration number.”

Ray doesn’t suggest how he reads an au pair’s mental notes as he drives past, but perhaps that offhand “some au-pair” tells us what we need to know. For Ray, other human beings tend to present as categories or herds. He despises ordinary people and the ordinary things they do: those who barbecue in cool weather; parents who avoid kids’ books that are merely “ever-so-slightly racist”; shopkeepers who attempt chitchat.

He is borderline obsessed with a group of local kids, “the summer boys,” who play soccer on the beach near his house on warm evenings. Ray stays inside when these boys are around; he reviles them with bewildering force. He hates their low-cost identikit homes: “The housing estate houses are as young as the boys and just as indistinguishable from one another.” He also derides the boys’ mothers; when he sees one on the street he identifies her as such “from the way she has the face of a potato and the hair of a film star.” Ray’s disgust and fear are founded in the distress of his early life, and the novel gradually reveals its dismal consequences for him. Yet his vision of these women has a different sadness. We are shown little of them beyond the fact that they try to be something other than ugly, and fail.

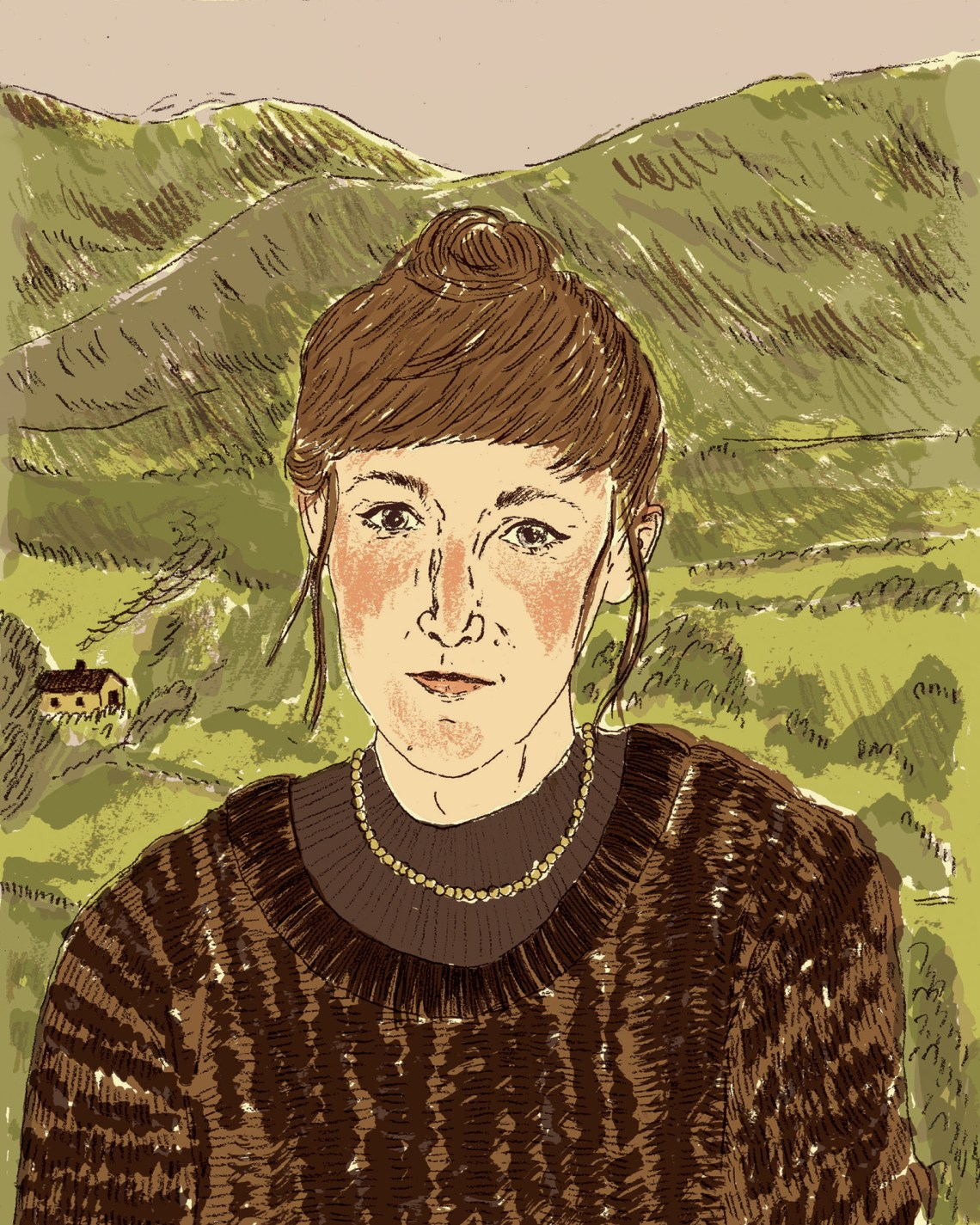

Baume’s second novel, A Line Made by Walking (2017), is the story of a twentysomething artist, Frankie, who has a breakdown after moving from Dublin to her dead grandmother’s rural bungalow. Baume works as both a conceptual artist and a novelist and has spoken about how this book draws on her own past. She has said that all her novels steer close to nonfiction—she describes them as exaggerations of her own experiences, “writing in extremity of my life.”

For a tale of mental collapse, A Line Made by Walking is surprisingly jaunty, full of droll escapades and comic neighbors. Frankie, who narrates the book, is intermittently floored by despair, but between these episodes she shouts at nuns on the television (“BOLLOCKS TO GOD!”), undertakes an art project assembling images of roadkill, and digs a deep hole on the beach with her bare hands—“I stand in my hole and pretend to be a dwarf.” She receives visitors, takes day trips, or rests at home in the company of the bungalow’s curios, including a foot-shaped pebble and a ceramic hippo.

Unlike Ray, Frankie has supportive parents and friends, but she is otherwise suspicious of people, and troubling in her tendency to belittle or humiliate anybody who is not extraordinarily generous to her. Perhaps this inability to dignify lives other than her own is a symptom of her distress. She is rude to her doctor, “a black woman in a purple shirt.” Frankie corrects her English and makes a comment about “your country.” Later she has misgivings about the interaction, not so much regretting her behavior as worrying about the consequences for herself. (Will she be classified as a racist in the doctor’s notes, and is she indeed a racist?) She launches a tirade at a group of (in her mother’s words) “mentally handicapped people, or whatever it is you’re supposed to say now.” A large woman seen briefly on a train cannot quite achieve the status of character: for Frankie, this woman’s fat “prevails over every other potentially defining feature.” Her presence in the novel is the springboard for a meditation on Frankie’s feelings. The fatter you are, Frankie informs us, the harder it is to lose weight. A pearl of wisdom is on its way: the worse things are, the harder it is to set them right. “But this applies to every aspect of life. How can it be that the very fat people didn’t know?”

On the same train a trolley attendant hands Frankie a stirrer for her coffee even though she did not ask for sugar or milk. And this is no isolated incident: the same thing has happened before, with other trolley attendants. Frankie, the artist, considers amassing stirrers as a conceptual work, a comment on how “people don’t listen, don’t think.”

Advertisement

You know the feeling—sometimes called l’esprit de l’escalier—that comes when you think of a brilliant riposte long after the conversation is over? At times I feel this is what I’m reading when I read highly autobiographical fiction—novels that are written to showcase just these lines as they persist in the author’s mind. Peripheral characters who differ from or disagree with the narrator (whose life shares various features with the author’s) are shown to be unappealing or ignorant, and the small irritations of daily life, all those coffee sticks we never asked for, are discharged in a plot that is determined to establish fault.

A Line Made by Walking, like Spill Simmer Falter Wither, is a tissue of such small, aggravated interactions. They make up the main substance of the novels, though they are rarely instrumental to plot or character development in any conventional way. This isn’t unique to Baume, or even to autobiographical fiction. It’s one of the many things that a novel can do—novelists are only human, and there are worse ways to settle scores than to write a grumpy book. On rare occasions an author like Thomas Bernhard or Rachel Cusk will really let rip and make something original out of their grievances. But most books lack their focused intensity, and a story can stunt itself when it is unable to be interested in its own population. It comes as a stroke of inspiration, then, that Baume’s new novel is about two people who choose to make a radical break from society, avoiding interaction with other humans whenever they possibly can.

Seven Steeples tells the story of Bell, a woman, and Sigh, a man, who move with two dogs, Pip and Voss, to an isolated cottage at the foot of a mountain in Ireland. Again, the novel is based on autobiography—Baume’s move, with her partner and dogs, to a cottage in rural Ireland. The “extremity” is this: over the novel’s seven-year span, Bell and Sigh gradually cut off contact with the human world. Where the book does encounter other human characters, they must be endured. (Members of the public are variously described as a blight or a pestilence, or simply “loathed.”)

Overall, though, this book is gentler than its predecessors, in part because it just doesn’t see other people that much. It turns instead to something it calls the “eye” of the mountain, using a detached third-person perspective that’s able to see into everything in the area, “through bracken, brick, wood, cement and steel.” The steeples of seven churches are said to be visible from the summit, and the book as a whole accounts for this space—a zone that extends, in a plain sense, across streets and fields to the sea. So what kind of novel does a mountain write?

Occasionally its narrative extends beyond anything a person could perceive, recounting the death of a wild mouse alone in a woodland, or describing events on a local road when nobody is driving or walking there:

The mountain witnessed

the stump-legged horse jump its wall to shit on the road, and every piece of hardware that fell and rolled. It witnessed the Lucozade bottles and takeaway boxes cast from car windows after dark, the gloves lost by careless, warm-handed walkers.

Most of the story, though, offers an exquisitely detailed report of the environment as it is experienced by Bell and Sigh. We witness the toast crumbs that gather on the surface of the butter, the “pin-leafed” foliage of wild thyme, “a diamante of fish skin” that is caught after dinner in the curls of hair on Voss’s back, a “cantankerous robin” in the garden hedge. We meet the sofa—secondhand and upholstered with a stained fabric bearing Latin aphorisms.

There is much to say about the material world of the cottage—notably, its dirt. The indoor atmosphere is composed of “sticky dust, shedded fur and old smoke.” Dog-bowl grime is a “russet-coloured mucus.” A grease mark at hand height on an interior door is “the combined palm-marks of several years’ worth of slamming.” The splits between floorboards have acquired a crust whose components are itemized. Several passages tell the story of an old blue bath mat that was inherited with the house and hangs on a washing line in the garden. Bell and Sigh never think to take it down and so it becomes “a small section of the steadfast panorama.” It is possible that the blue bath mat “might not have popped out of the sea and the sky, but soaked them up instead.”

Advertisement

The mountain’s narrative is given to flights of fancy like this, and its language is rich—dinner is never cooked, it is “mixed, blitzed, coddled and braised into secondary and tertiary colours.” As we come to know the household and its daily activities, we see that this slightly fey tone is appropriate. Bell and Sigh walk with their dogs, cook, and perform “daily ceremonies.” They create a shrine with origami doves and periwinkle shells surrounding a plastic figurine of Elrond, the elf king in Lord of the Rings. They meditate on an astonishing potato. They make shopping lists, also itemized on the page: “Tahini, floss, scrubbers, pumpkin seeds, curry powder, matches, cloves.”

Seven Steeples is a peculiar and distinctive book: the adventures of two people and two dogs who go feral on a mountain and sometimes shop for tahini. I like that about it. Baume does her own thing. Perhaps this is why she is such a likable writer, despite her unforgiving narrators—she receives admiring reviews and endorsements, and her writing has won or been nominated for many literary prizes. In all her novels, but especially Seven Steeples, I had the feeling that she knows exactly what it is she needs the book to do. Each novel has its own conception, while partaking of a shared Baumeish atmosphere. A doggy, dirty house, a clapped-out car, a meal of tinned vegetables dumped in a crusty frying pan, a whole lot of alliteration. A universe whose bleak nastiness is tempered by its silly sense of humor. Baume’s protagonists lurch through minor and major catastrophes, glaring at other humans with a hatred so baseless and often so bonkers that it’s hard to take it to heart.

One of the brilliant particularities of Seven Steeples is its intelligent and satisfying portrayal of time. The novel is told over seven years in seven chapters. It also passes through a single cycle of seasons from January to January. So Bell and Sigh’s early years at the cottage, at the beginning of the book, are seen in winter. In the middle of the book they have been there for a few years, and the scenes describe the house and countryside in summer. By the end we have reached the seventh year of their residence and returned to winter. This structure has an accretive quality, contributing to a folded experience of time that holds together the incremental and the sweeping, the linear and the cyclic, the exciting and the repetitive.

The novel also has a formal design on the page, more generic but striking nonetheless. It is told in paragraphs surrounded by white space, so that each page has a few floating islands of text. At the end of many of these paragraphs, sentences are stepped or broken across the page, with long white spaces midline. This lends the book an experimental look, although it doesn’t undertake any formal experiment: this is a playful mode that refers to modernist innovation but is settled in its ways—a genre in its own right, with its own particular terms of engagement in the twenty-first-century novel. I thought of the English novelists Maddie Mortimer, Max Porter, and Rebecca Watson, among other writers who do something similar: words float and slide across the page, or lines are unexpectedly broken. Squint and it looks as though novelistic conventions are disintegrating before you; there has been talk of a “new modernism” among some of Baume’s contemporaries, including Claire-Louise Bennett and Eimear McBride, because of their use of fractured forms and wordplay. This isn’t The Waste Land, though—the fragmentation of language appears, here at least, as an exuberant means of expression.

In Seven Steeples the line breaks portray something. The spaces make pictures—of a lapse of time or a physical space. The length of the body:

the level of her belly, his belly her feet, his feet.

The moments, between Voss’s barks, in which Voss is listening, or the space Pip jumps across between two mats on the floor:

from rug-island to rug-island

without ever touching the lino.

When you leaf through Seven Steeples it looks similar to novels by Porter and Mortimer in particular, and when you read it more carefully, it has a similar verbosity—that exuberance again, an attitude to language that is joyful and (Bell and Sigh would like this) a bit puppyish. These books rearrange their lines of prose without any drive or consequence beyond the immediate scene and subject.

It’s a way of writing that has separated itself from the force that compelled similar modernist forms in the twentieth century, especially in Ireland—a pressure to break down the English language and its English institutions. (Angela Carter described James Joyce’s wordplay as a “magisterial project”: “Buggering the English language, the ultimate revenge of the colonialised.”) Baume’s playful approach to the line, by contrast, is an emphatic presentation of the area of linoleum between two rug-islands. But that’s right for this book, which is earnestly concerned with particulars. I think this earnestness, more than the fun, is the novel’s grace: its narrative is concerned in a literal way with the floor, the dog hair, the pumpkin seeds, and the russet material coating the dog bowl. Baume is interested in dailiness, personal habits, and ephemera, as she has described in her previous book, handiwork (2020), an essay on her own life and practice.

This must be why the departure from human society, which seems significant at the outset of Seven Steeples, comes to feel like no big deal in the long run. As the gap between Bell-and-Sigh and the rest of humanity grows, its significance shrinks. They visit town less frequently, change phone numbers, and lose the TV connection. They wonder in a desultory way about “the bits and pieces of family they had left behind” and then settle the matter, “as had become their habit, by doing nothing.”

You could say that the novel is liberated from emotional entanglement. Bell and Sigh have minor housekeeping disagreements, but they don’t really argue and they don’t have sex. (It’s not seen or heard in the cottage, anyway, even as we watch the little sipping motions they make as they sleep, and listen in to the “gurgles, squishes and pops” of their digestive systems.) During the day they pick ticks out of the dogs’ fur and at night they lie awake, thinking about ticks.

At the end, the book gestures to some more significant event that may be happening in the outside world, but it feels noncommittal, remaining vague and undefined. (When I put “seven steeples” into a search engine the autocomplete function suggested “seven steeples ending explained.”) For Bell and Sigh the world is full, and calmed. Ubi amor, ibi dolor, as the wise old sofa says.

If Baume isn’t very concerned with the love and pain of the world that Bell and Sigh depart from, it’s because she is intent on where they arrive: all that dailiness, examined with extraordinary care. The novel reads as an outpouring of description—at first. As an experience of slowed-down attention, this alone is worth a reader’s time. Beyond that, focus at this resolution is unusual. Anybody who has ever read a book on how to write fiction knows that a bath mat belongs in a story only if it indicates some telling detail about the protagonist or if it’s to be used as a murder weapon. This approach to narrative is not universal but it is familiar. We might observe that it is an ethos of annihilation—it eradicates the intrinsic value of everything beyond the main characters, so it’s a nice fit for a species bent on the destruction of everything outside ourselves. We might equally observe that as an approach to storytelling, it has led to some very good books. The bath mat in Seven Steeples declines all such narrative functions. It doesn’t affect the plot, nor does it tell us anything urgent about Bell or Sigh. So what is it doing?

Over the course of Seven Steeples, we come to see that this circling attention to objects, animals, and surroundings cannot be read as descriptive. Things are happening here. The robin is not a plot device, a symbol, or a start of movement glimpsed in the background: he is his own subject, an angry guy. One day he will have to confront death. What will happen then to the territory he has defended with such hostility? The book stitches together miniature sequences on the robin, the potatoes, Bell and Sigh’s van, among much else. Even the crumbs on the butter have to go somewhere. In this the novel recalls the attentive depersonalization of the nouveau roman of Alain Robbe-Grillet and others, though Baume’s sequences use technical description less as a means of exposition. Rather, she examines how constellations of matter form, break, and regroup. She gives us an awareness that robins, bath mats, and household crud exist in our world, and events happen to them. Consequences, even meaning, feel within reach.

In summer, Bell and Sigh avoid the crowded beach during the day to swim in the quiet bay in the evening. Seaweed and cold water press against their bodies and make them feel alive: “They did it as a means of remembering their surroundings; of being reminded that they were each made out of surroundings.” The novel leaves me wondering what the surroundings make. Misanthropy is a condition of its vision, which implies that it is not so easy to care about the robin’s story while tolerating the blight and pestilence of people. As with Frankie’s breakdown high jinks, I had the sense that Seven Steeples averts its gaze from some of the more difficult experiences and relationships of the world it so devotedly describes.

Even a novelist who chooses not to depict feeling isn’t necessarily giving up on the hope of creating a felt experience. But love and pain, conventional subjects for the novel, are also a matter of the surroundings (perhaps more instrumental than ever now, in an anthropogenic geological epoch, as human needs and wants are changing everything, everywhere), and they’re powerful. So it feels like a lot to lose. I hope that new stories like Seven Steeples will teach their readers to be moved by a robin, seaweed, or the fall of a bath mat—enough to want to know what happens next.