Paris in November. The rain was unrelenting, people huddled in cafés, and umbrellas knocked heads in the cramped streets. Scooters, bikes, and buses zoomed by, spattering muddy water with little regard for pedestrians. Everything felt taxing—even the metro was a mess. The only people engaged with life at a normal speed were those with dogs. “Courageous citizens,” Etel Adnan writes of them. “The people and the animals get wet, but there are unavoidable duties to perform, and they follow the rule.”

This might be true of many places, but it took reading Adnan on Paris to make my peace with it. I had arrived from always-sunny Cairo some weeks earlier, along with my large and active dog, and was somehow ill-prepared for even the rain, let alone the hassle and duty of negotiating it. I began reading Adnan’s Paris, When It’s Naked, and it was, it turned out, a timeless field guide to the city. Early in it she writes:

And you will never die of thirst, in this city, as in African deserts; your skin will never dry out, your complexion will remain pleasant. Although you’ll never have the pink cheeks of English princesses, unless the Common Market really works. For the time being, try to find some little joint which has a good inexpensive Bordeaux sold as house wine, because rain makes your pocket and your throat feel dry. And then, look at Paris, do it in your imagination if your eyes can’t find it, and see what a solid mass of a city it is, what a fugue in its composition, what an epic story in its stones, what an evanescent spirit in its rain.

The Lebanese-born painter, poet, and essayist passed away at her home in Paris on November 14, 2021, at the age of ninety-six. She once said that she wasn’t sure about destiny, attracted though she was to the idea of it, but she seemed to believe at least in symmetry (“There is something called timing in life”), and I imagine she would have thought it made perfect sense that I read her Paris book soon after my arrival and into the month of her death. The question “How and when would I die?” seemed to occupy her:

Let’s be direct: you think of death. And what is death? Disappearance, I should say. A magician’s trick: here’s the handkerchief, here it isn’t! No. It’s something else. It’s inbuilt in life. But that doesn’t say what it is, it being the end of life. Death is not a fact. It’s a judgement passed on fact, accompanied by pain, or, rather, by fear. Fear of what? Fear of death. I sit in my café and keep reflecting, pushing here and there.

In Time, a book of poems, she writes, “I say that I’m not afraid/of dying because I haven’t/yet had the experience/of death.” Yet she repeatedly put to paper her sense of it, or at least her general apprehension about losing time:

Death moves in

like a soft

wind

between

layers

of dread

Born in Beirut in 1925, when Lebanon was still a French colony, Adnan was the only child of a Greek Orthodox mother from Smyrna (now Izmir) and a Syrian father from Damascus who had been a high-ranking officer in the Ottoman army and a governor of Smyrna. She grew up speaking Greek and Turkish at home and studying French in school. A quiet child by her own description, she spent her days observing flowers, flies, and the family dog; as a teenager she had an appreciation for the smell of Beirut’s orange trees and immersed herself in what music and poetry she could find. At twenty-four, after working in a local press office and concurrently, for an intense few months, attending the École des Lettres (“This is where and when I convinced myself that poetry is the purpose of life”), she left on a scholarship to study philosophy at the Sorbonne.

At her French convent school in Beirut, she was taught to “consider France the center of the world,” and so ending up there was inevitable. It was at the Louvre that she saw paintings for the first time (in Beirut, carpets were the art that hung on walls), an experience she described as impressing her “beyond what you could dream of.” In 1955 Adnan went to Berkeley, then Harvard, and eventually took a position teaching the philosophy of art at the Dominican University of California in San Rafael, where she again discovered painting—her own this time. (The story goes that the head of the art department asked how she could teach the philosophy of art if she didn’t make art herself, and invited her to do so with a box of pastels.)

Advertisement

Adnan’s father had died by the time she left Lebanon, and she was never able to find common ground with her mother. She had wanted to be an architect, which her mother disparaged as a man’s job. The tension between them was constant, but it hadn’t made leaving Beirut any easier: her mother was devastated by her departure, a guilt that Adnan said she lived with forever. And yet her formative years with her parents seem to explain much of what came to define her life. “I was living with two people who had been broken, defeated, very young,” she said in an interview. “My mother had lost her home city, and my father his army and with it his whole career and life.”

Although she often told friends and interviewers that she never thought of the past and lived only in the present, Adnan was nonetheless preoccupied with Smyrna—if not as an actual city, I imagine, then as an experience of loss for her parents, and what that loss had done to diminish them. It was perhaps also the place of imagination, of who her parents might have been before they had her, the people she late in life said she wished she had been able to get to know as friends.

In the late 1990s Adnan met the Lebanese artist and filmmaker Joana Hadjithomas, whose grandfather had also been haunted by his exile from his childhood home of Smyrna. The two immediately hit it off and together they kindled a dream of visiting the city. They talked about a hypothetical trip for several years, but Adnan could no longer travel by plane due to a heart condition. Instead they made a film, ISMYRNA (2016), which is set in Paris and tells the story of a voyage to Smyrna through images and conversations between them. In the film Adnan says:

The only thing left is oral transmission. If you suppress it, there is nothing left. My grandfather said, “Since there are no letters, no archives, no photographs…there is nothing concerning that famous grandfather, except what his son recounted.” So recounting for us practically meant survival.

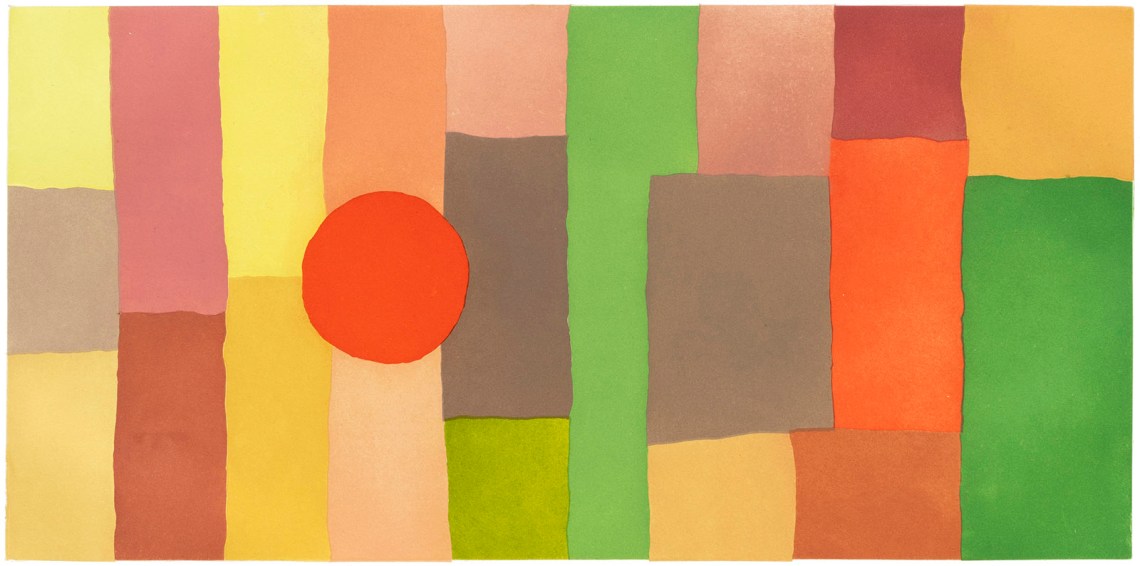

Adnan had internalized the experience of her parents: the defeat, the breakage, the lack of photographs, letters, thoughts. She lived her life maximally—writing, painting, speaking, drawing, whatever, it seemed, came to mind. Her paintings (small, abstract, bright) were most often completed in a single sitting (“because I’m compulsive”). Texts (I’ve heard) flowed out of her in one shot—unedited. Leporellos—notebooks folded accordion-style—became a favorite, thanks to a friend in San Francisco who gave her a mostly empty Japanese one. Reality and fiction were interchangeable, taking the form of complete stories as well as fragmentary texts, letters, prose. Poetry was a constant.

Textiles came later, perhaps out of a subconscious desire to revive the form that had existed in the Lebanese homes of her childhood. (When asked why she began making tapestries, she answered that she didn’t know.) She had thoughts, questions, about everything: “As earth doesn’t expand, power does, and may get out of hand.” “Why did we invent sky deities?” “And what do police say when they realize that suicidal women could be beautiful?” “Do senses precede the soul?” “What happens in a cat’s brain when a cat decides between jumping and not jumping? Does his whole body think?” “Are the rockets shooting for the moon killing invisible animals along the way?”

Adnan was in constant physical motion, too. In Of Cities and Women (Letters to Fawwaz), she writes to her close friend the Lebanese historian and writer Fawwaz Traboulsi over several months from Barcelona, Aix-en-Provence, Skopelos, Athens, London, Spain again, Amsterdam, Paris, Berlin, and Beirut. Although the book is cast as fiction, everyone who was close to her said she wrote of what she knew and where she was:

Paris, late September; I’m home again, after a trip that was complicated by a stop in Salonica. I am ready to mail you my letter from here, but before doing so, I must tell you one more thing….

I have lost the memory of the voice of my parents. I went to Greece hoping to hear the Greek spoken by my mother. I listened closely, and it seemed that no one spoke the way she did. I was telling myself that perhaps the Greek spoken in Smyrna was different: more musical, more passionate (it seemed to me) than the one I was hearing, which seemed too rapid, too neutral. In any case, I was unable to find the voice I am seeking.

It was this restlessness and sense of urgency to see and document and create in every form that earned Adnan her cultlike status, first in Lebanon among poets and artists, and later as an artist in the wider world. Her first novel, Sitt Marie Rose, which she wrote in one month, was based on the true story of a schoolteacher who was abducted and killed by Christian militiamen in 1976 during the Lebanese Civil War. It was published in France in 1978 and banned in Lebanon. Told from the perspective of five characters, all of them partially recounting their thoughts on Marie-Rose, it laid out the complex situation of the Lebanese war across class, religious, and economic divides, using lyrical fragments of journalism, news items, conversation, and monologue:

Advertisement

On the thirteenth of April 1975 Hatred erupts. Several hundred years of frustration re-emerge to be expressed anew. Sunday noon a bus full of Palestinians returning to their camp passes a church where the head of the Phalangist party and other Christians are celebrating the mass. That morning a Phalangist was killed in front of that church. A laid trap or simple chance, no one knows, but militiamen stop the bus, make its occupants get off, and shoot them one after the other. The news crosses the city like an electric shock. A silence falls over the whole afternoon. Everyone senses the impending doom. At night, explosions shake the city. Machine gun bursts are heard at closer and closer intervals.

Significantly, Adnan had an opinion about almost every political event that occurred in her lifetime. Her lifelong partner, the sculptor Simone Fattal, said that “Etel spends all her night reading the newspaper,” recapping everything to her in the morning over breakfast. About the first high-resolution lunar images in the early 1960s, she wrote in Journey to Mount Tamalpais:

I will always remember the day Ranger 8 hit the moon. It was a Saturday, in February. It sent back the first close-ups of the craters and of a face which was pocked, rubbery, like burning milk breaking up in bubbles, and stretching its skin….

On the same television program appeared Red China’s first nuclear explosion….

Ranger 9 took off from Cape Kennedy and from the television set….

And if you like numbers, I will tell you that here on earth it was February 14th, and it was spring: flowers were all around and a warm breeze was mixing my fever with the clouds.

On the Vietnam War, from a newspaper article in 1972:

Every evening at 6 o’clock, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and for one hour, the local news—which is on a continental scale—and international news are broadcast on American television. The main show of the day covers all events with deliberately dramatic style and a hundred million Americans sit in the dark to watch an ever familiar, but never repeated, spectacle.

In this way, and for ten years, the Vietnam War has seeped into the American psyche: a strange war that nobody sees, it takes place on foreign land, a ghost that haunts each family but that never manifests.

On the Gulf War, in Master of the Eclipse:

While drinking coffee I am in the midst of the Gulf War: a movie is passing in front of my eyes but the images are not in black and white, they are the color of my skin. They tell me that Iraq is being crushed under bombs and warn me to be careful, not to show too much emotion, to keep my worries under a lid when they are of no interest to most people. This recurring need for dissimulation creates a kind of shield, a second self so to speak, that censors thoughts, or sometimes erases them altogether.

Adnan started writing when she was around twenty and never stopped. (She referred to her paintings as writing, too, and vice versa, and she painted flat, on a desk.) Her observations—literal, profound, provincial, philosophical—span everything from A to Z (she even has a book by that name, one of her most linear, in its focus on the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979): “One being escaped the total fate of Arab women: Oum Kalsoum.” “Women and exile are linked. The Vauvenargues Buffet, an enormous canvas painted by Picasso in the last decade of his life, is thus exhibited in a room adjoining the Sainte-Victoire exhibition.” “Thinking wouldn’t function without memory, for even the present is memory aware of itself.” “Pain is neither masculine or feminine but rather androgynous.”

Outer space was an ongoing fascination (she composed an eleven-part poem and leporello to the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin) and became a continuous thread through her work. The root of her passion was as simple as “the impossible becoming possible,” with all that implied. This proved to be a lifelong gift—a sense of awe toward almost everything, including the cosmos:

When I was five years old, my father would point to the moon. And he used to tell me: “Do you see the moon? We will never go there.”…And then we saw the astronauts and they related extraordinary things, the Russians and the Americans. Komarov, the Russian, said he saw 17 sunrises in one day, in one terrestrial day. And it was something mind blowing, really. It was a big adventure that topped the ’60s. When, in the ’60s, the world looked like a continuous miracle. And that was an incredible thing. We left the earth with them.

Decades later, in The Cost for Love We Are Not Willing to Pay, she saw a moral price to our leaving earth:

More and more people behave as if they ignore Nature, dislike it, or even despise it. We wouldn’t have ecological catastrophe in which we live if it were otherwise. They absolutely cannot understand Native American Chief Joseph’s response to American settlers when they tried to use Indians to plow the land: “How can I split my mother’s belly with a plough?”—and he meant it not metaphorically, but literally. After all, Earth is mother. It sustains life. We come from it: religions say it their way; science says it too, as well as common sense. So we do not love our first, our original, mother. We quit her. We left her behind. We went to the moon.

Although there were many fans of her philosophical poems and ruminations, including her thoughts on the Muslim philosopher Ibn Arabi, Adnan was really at her best in writing about war and its impact on everyday life, including exile. She captured with astonishing perception what it means to live in a place where everything is under strain and the sense of time is all in the waiting—for catastrophe most likely, or at least some tenor of change. “War and revolution make a country important until it then falls into the turmoil of constancy and disappears from importance,” she once said.

Beirut was Adnan’s case study long after she left it, but this turmoil of constancy she wrote of may well be applicable to any country in which the United States has intervened (Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, Palestine—she writes about them all) as well, of course, as the Arab world at large. In her book-length prose poem The Arab Apocalypse, which in her kaleidoscopic style tackles the general predicament of history and humanity, and the specific plight of the Palestinian refugee camp of Tel al-Zaatar under siege, Adnan uses symbols where words no longer suffice. “Prayer beads,” she called them, filling in for what could not be said. Whether these symbols worked or not (this is debatable) didn’t detract from what she was trying to say, gesturally with the form and literally with the words she found for the poem:

When the living rot on the bodies of the dead

When the combatants’ teeth become knives

When words lose their meaning and become arsenic

When the aggressors’ nails become claws

When old friends hurry to join the carnage

When the victors’ eyes become live shells

When clergymen pick up the hammer and crucify

When officials open the door to the enemy

When the mountain peoples’ feet weigh like elephants

When roses grow only in cemeteries

When they eat the Palestinian’s liver before he’s even dead

When the sun itself has no other purpose than being a shroudthe human tide moves on…

It is in Adnan’s simplest work—most direct, most grounded, most straightforward—that her writing is at its most penetrating. In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country, a slim book collecting seven texts, she takes this more earthbound approach in several directions, with sharp observations that she revisits over time:

WEATHER

In Beirut there is one season and a half. Often, the air is still. I get up in the morning and breathe heavily. The winter is damp. My bones ache. I have a neighbor who spits blood when at last it rains….VITAL DATA

The most interesting things in Beirut are the absent ones. The absence of an opera house, of a football field, of a bridge, of a subway, and, I was going to say, of the people and of the government. And, of course, the absence of absence of garbage….PLACE

I left this place by running all the way to California. An exile, which lasted for years. I came back on a stretcher and felt here a stranger, exiled from my former exile. I am always away from something and somewhere. My senses left me one by one to have a life of their own. If you meet me in the street, don’t be sure it is me. My center is not in the solar system.

And from the end of the book, in a piece entitled “To Be in a Time of War,” a searing essayistic poem written during the Iraq War, while she was in California:

To do as if things mattered. To look calm, polite, when Gaza is under siege and when a blackish tide slowly engulfs the Palestinians. How not to die of rage? To project on the screen World War I, then World War II, while expecting the Third one. To scare the innocent, by following the Israeli way of spreading terror. To make a phone call to Paris. To tell Walid that things are all right. To lie. To admit that the weather is noncommittal, beautifully. To feel indifference toward a spring suddenly heating up. To choose which shirt to wear. To fill one’s mind with the apprehension of the Sunday paper there, at the door.

It was also in this book that Adnan wrote of language, which was both her exile and refuge. Her childhood in Lebanon had been so fractured that there was no single audience, no way of communicating fluently, freely. It depended on who you were—your class, status, age, family history, whether you spoke Greek, French, English, Turkish, or Arabic. Adnan wrote in French until the Algerian War of Independence, at which point, repelled by the massacre of Algerians at the hands of French forces, she switched to English—or rather American, she told an interviewer:

I say American because it has an energy, a history, a connotation all of its own…. In French, if you take liberty with the language, people correct you…. And that doesn’t happen to me in the United States…. You create your language, you have a freedom with your language,…so that’s extremely endearing.

America alleviated many of Adnan’s sorrows, but for someone who claimed to live only in the present, she had her fair share of regrets. She often mentioned Arabic as the written medium she wished she had, but it seemed too late, in a life so full, to learn to write in it as fluidly as she did in English or oils or French. Instead she turned to experiments in form. And to a mountain: Mount Tamalpais, just north of San Francisco, which was the resolution of her exile, if leaving exile means shaking off what one longed for. “It saved my life,” she said of the mountain. “As soon as I saw it I felt at home. It became the…axis around which I turned. Sometimes a person does that to you.” Of California she said, “I was happy.” It was, in the end, the place that gave her Arabic, through the calligraphic Arabic poems she came to paint by sight, and the mountain that she painted repeatedly until her death.

And this is what is most striking about her paintings—this Arabic of hers—the lightness they convey. This mountain, this form, this freedom, was the counterbalance to everything Adnan had lived and all the horrors she had documented. Even as they carry titles such as Le Poids du monde (The Weight of the World), her paintings—fast, heartfelt, joyful—were the resolution of a life fully lived.

It was these tiny abstract canvases that also catapulted Adnan in the last decade of her life to an elevated fame—her work was shown extensively, including at Documenta 13, the Serpentine Gallery in London, the Museums of Modern Art in San Francisco and New York, and, just before her death, the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Although it never changed her (it was too late, she said, to even have a use for the money), the art-world stardom folded her into the contemporary art canon and, by turn, helped resituate art from the Levant and the wider Arab region. That celebrity also gave rise to the repeated question of why Etel—of who she actually was: a queer Arab woman, exhaustively knowledgeable, dizzyingly productive, almost a century old, who offered no apologies, no explanations, no coming out, no deference, no compromises, and simply a model of how one could exist on sheer will.

Two evenings after Adnan’s death, the Lebanese artist Lamia Joreige knocked on my office door in Paris, where we were both on a residency. The two had been close, and Joreige had recently completed a film based on one of Adnan’s poems, Sun and Sea. It had been an ongoing conversation between the two: Adnan had read the poem aloud to Joreige a decade earlier, inviting her to turn it into a visual work. It had taken years—mostly of hesitation—and Joreige had finally shown the film to Adnan a few weeks earlier in Brittany, overlooking the sea, on what became Adnan’s last visit there.

Joreige shook her head in disbelief that she had made it in time, as well of course that her friend was gone: “Last time I saw her, she said she was tired, ready, but with Etel you expected her to somehow be here forever.” I had all of Adnan’s books laid out on the table, some open, some closed, others in piles. Joreige got up and paced my office for a while, picking up one of the books and flipping through it. At random, she read:

The morning after

my death

we will sit in cafés

but I will not

be there

I will not be.

This Issue

June 8, 2023

Getting Sacagawea Right

The Price of Crypto