James Weldon Johnson was critical of dialect because it had only two stops: pathos and humor. Mark Twain may have listened to how the black people around him spoke, and the case has been made passionately that he gave his black characters credit for thinking at a time when dialect was used mostly to confirm the inferiority of black people, but even if not racist, dialect is still racialized speech. It contains the problem of having to overcome the assumption that racial distinctions will be demeaning for black people.

The only character who speaks in dialect in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s Civil War novel, The Fanatics (1901), is the “negro” bell ringer in the Ohio town that hates black people almost as much as it does the rebels. Dunbar could not drink away the self-doubt he had because white critics preferred his poems in dialect to those in what was once called standard English. One language for the master, another for the slave, George Washington Cable said. Charles Chesnutt tried in his work to present a realistic picture of the South at the turn of the twentieth century and was exasperated by the huge market for the literature of Uncle Remus–style folksiness. Chesnutt argued that there was no such thing as “Negro dialect”; it was just white writers trying to come up with phonetic spellings of what black talk sounded like to them.

In the folk realism of Porgy (1925) by the white South Carolina writer DuBose Heyward, black people do all the talking, and in a dialect that supposedly reflects that of the Gullah people of the Carolina coastal region. The dialect is not easy, and Heyward’s intention may have been to make the thoughts expressed poetic, because the story itself is finally about something that cannot be explained.

Julia Peterkin, Heyward’s contemporary, portrayed isolated Carolina black communities in her fiction, as if showing blacks in an autonomous setting without the dangers of racial politics would present them in their best light. Peterkin is preoccupied with the Gullah dialect and customs: the birth suppers, the quilt-making parties. However, though her black characters have folk wisdom about how to read a landscape and listen to bird calls for signs, they have no conventional sense of morality. Her characters supplement Christianity with Conjure, and a womanizing preacher in Peterkin’s Black April (1927) is tricked into marrying a girl he didn’t know was his daughter. In Peterkin’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Scarlet Sister Mary (1928), the black woman protagonist has eleven children by seven different men.

Zora Neale Hurston perhaps conceived of her heroine in Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) in part as a rebuke to Peterkin. Although Hurston mentions, in a letter written in 1935, that she had lunch with Peterkin and got on well with her, she minded the success that white writers had with black folk material. The black novelist George Wylie Henderson was seen as a follower of Peterkin’s. He has plenty of black folkways in his Ollie Miss (1935), and at the same time he tries to protect his black woman protagonist from stereotype by cordoning her off, not letting her talk much, making her as strong as a man in the field and gloomily taciturn, unwilling to share with others how sad her love is. But in Their Eyes Were Watching God, Hurston offers the story of an independent black woman capable of romantic love and of talking about it.

Hurston’s biographers tell us that early on in her career she had difficulty separating the folklore she collected from the fiction she was writing. Hurston wasn’t troubled by dialect. It was not to her the most important thing about the idiom of the Negro. She valued the flowing, poetical style of blacks and their cultural tendency to think in images, as she called it. Moreover, where portraits of black peasant life in the South tended to focus on impervious settings, on unchanged cultures from which the shape of the past could be inferred, Hurston enlarged the scope of folklore. For her, folklore, “the boiled-down juice of human living,” was movable, renewable. Some of her black critics complained that her portraits of all-black communities were a form of pastoral, but the outside world impinges on Hurston’s black community in her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934), when mass migration kills off the agricultural economy and empties the black church. Everybody has gone North.

What first distinguishes Richard Wright’s work from Harlem Renaissance writing has to do with his attitude toward urban living. Novels about Harlem migration tend to emphasize the sheer exuberance of being there. The voice of the displaced black person immediately after World War I in Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem (1928) is still countrified: “‘Doom, mah granny,’ retorted Zeddy. ‘Ef that theah black ole cow come fooling near me tonight, I’ll show her who’s wearing the pants.’” In Wright’s first novel, Lawd Today!, begun in 1931 but unpublished in his lifetime, the talk of a black urban culture that Wright captures is far from dialect. Black speech is intimate, yet virile. Any hankerings for the South are curtailed by memories of lynching. Wright’s casually brutal Chicago migrants prefer films with urban rather than rural stories. The idiocy of rural life, Marx said.

Advertisement

Wright’s first published book, Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), a collection of stories set in the South, is full of white violence and has no black ritual, no black music. He was after a kind of naturalistic detachment, not entertainment. The paranoid black psychological interior would become Wright’s domain. He needed speed in order to convey the feeling of being always hunted, of having to be always vigilant. Wright’s dialogue in his southern stories has no dialect punctuation that might make words sound or look quaint, no apostrophes to slow things down.

Moreover, like Hurston, Wright expanded his definition of folklore. It was in everything, it was everywhere, down to “the swapping of sex experiences on street corners from boy to boy in the deepest vernacular,” he notes in his essay “Blueprint for Negro Writing” (1937). He identified folklore as the “most indigenous and complete expression” of black life. It gave black communities the sense of a common life. Wright recognized it as the culture from which he sprang—and the terror from which he fled.

In Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), a phantom black woman, a voice from the slave past, tells the narrator that freedom “ain’t nothing but knowing how to say what I got up in my head.” The sense of Harlem in Ellison’s novel comes not from any description of place. Instead, Ellison, the antinaturalist, makes an allegory of what had been previously shown through the hard-won realism on which the truth of what was then called the black experience depended. Language had been used to describe the reality of black people, but Ellison concluded that language itself was reality, urging his novel to travel through a variety of black idioms as it goes from the South to the North.

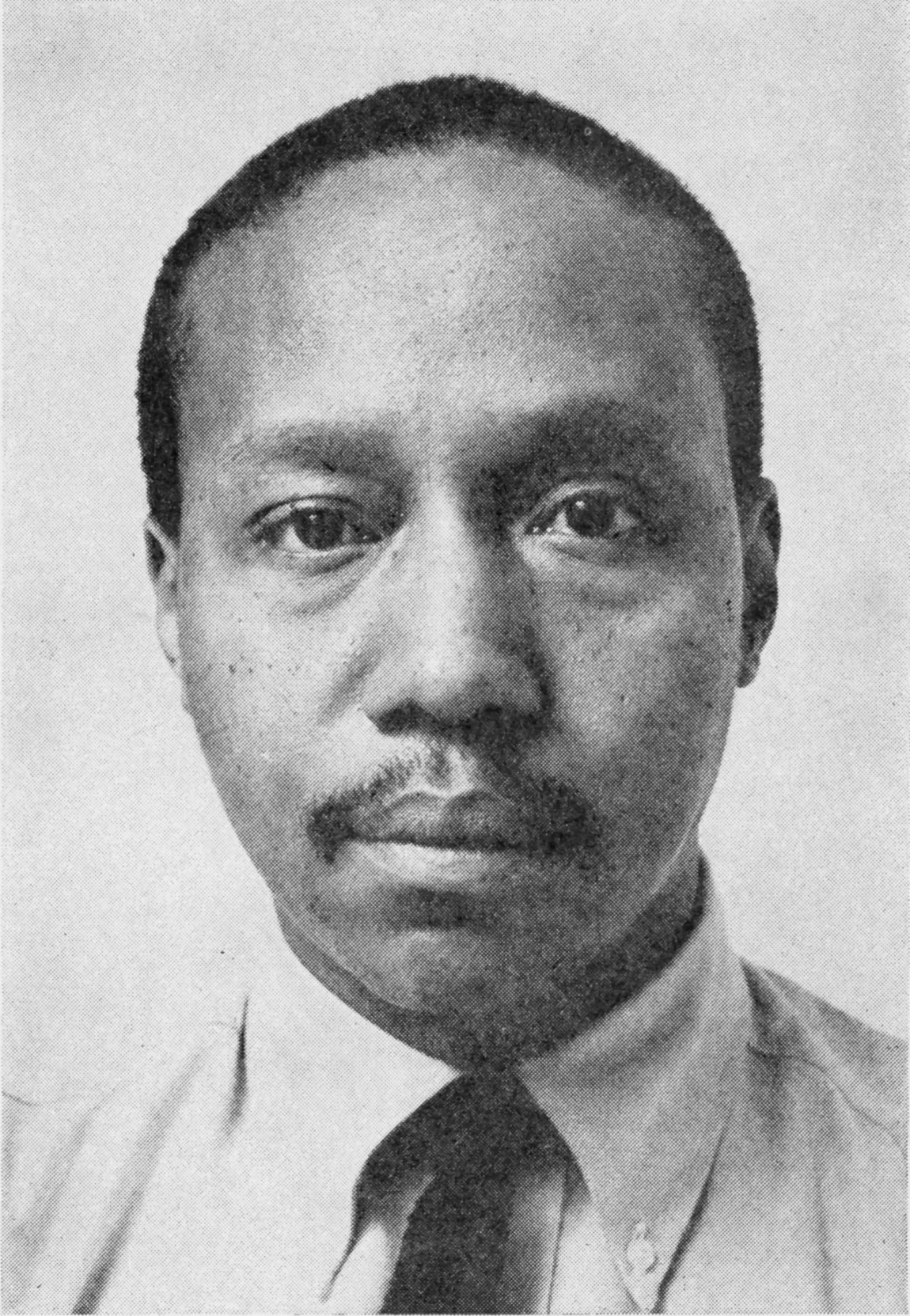

Black talk is again on the move in Lover Man, a newly reissued collection of melancholy stories by Alston Anderson originally published in 1959. Alston Anderson is one of those lost names of twentieth-century African American literature. In our present cultural mood of generous reexamination, the hunt is on for the forgotten, the overlooked, the could have been, and there among them is Anderson.

Born in 1924 in the Panama Canal Zone to Jamaican parents, he moved to North Carolina when he was fourteen. He served in the US Army and after World War II enrolled in North Carolina College, before making his way to Columbia and then to the Sorbonne, a drifter of the GI Bill generation. It took Anderson a while to get Lover Man together—a much-praised literary takeoff. However, his was the brief flight of a self-destructive soul, and before long his name had sunk in the darkness.

Because of the historical truth behind the authority of the autobiographical voice in twentieth-century African American literature, one critical bias held that the black condition was an unfair advantage as dramatic material. Hidden resentment led to interpretations of black fiction as more transcription of experience than literary invention, especially fiction written in the first person. And it was all about one thing, racial oppression. Ellison’s intentions were complex, but one aspect of his achievement in Invisible Man was the assertion of the first person as an overt literary strategy for the black writer. The first person was other things besides testimony, witness; it could be the instrument of a trickster, the writer.

While Ellison’s presence is on every page of Invisible Man, Anderson in Lover Man heads in the other direction, as if already in pursuit of his own disappearance. Each story is told in the first person (except one that is all dialogue). Aaron Jessup, whom we meet as a boy in “The Checker Board” and at different points in his growing up, is not the narrator of every story. Two of the collection’s narrators are women. Yet the fifteen stories are linked by family ties and community: someone who is mentioned or a secondary character in one story may be the focus of another. The stories are rendered largely as dialogue, with minimal first-person interiority. Sometimes a narrator is addressing a particular person, telling someone a lie, a tall tale. “I used on Miss Florence Tactiful Approach Number One For Ugly Women,” says the narrator of “Signifying,” who may be Aaron’s older brother, seen in previous stories dancing or building a shelf.

Advertisement

Anderson begins somewhere in the Black Belt, in the 1930s of people having to chop wood for the kitchen stove. His style is straightforward, but the simplicity is deceptive, the calm surface at odds with the depths sending up their clues. When the mother cries out the father’s name in the morning at the end of “The Checker Board,” the question is whether Aaron’s father is having sex with Aaron’s mother, or is absent, or has been found dead of natural causes, or was killed by Aaron’s brother, who has already left the house. Tragedies are absorbed in a line, as when Aaron ends “The Dozens” by saying he has not played the Dozens—an insult contest—since he helplessly watched Mutton Head, his best friend, drown in quicksand.

The settings of the early stories are usually “the town” or “my town,” and it’s seldom specified where the bus pulling in came from. In “A Sound of Screaming,” one of the longer stories, an older man takes a nineteen-year-old girl from their unnamed hometown to Kapalachee, Alabama, where he is paying for her backstreet abortion. Neither the woman abortionist nor her house is as sinister as he thought they would be. He leaves them, finds wine, tries not to think of anything, but can’t help picturing what is going on back at that house. When they get on the bus to return to their town, he knows that “the girl,” “that girl,” can’t go home, and he brings her to his place:

Her hair moving against the pillow made a sound like a whist broom when clothes are being brushed. She was crying. I wished right then that I could go through what she was going through: that I could do it for her then with her. But I didn’t say it. A man can’t say a thing like that to a woman and sound like anything but a damn fool, I thought.

As tender as his understanding is, he wants her ordeal to be over, to get back to their good times. “James, don’t. Oh, James, darling.” He is Aaron’s father, and the girl, Maybelle, is Aaron’s “play mother” from an earlier story.

At one point, the girl asks him to tell her something “funny.” He recites a toast about a crapshooter, Sam the Man. “He was a killer from way back./He’d fall into town sharper’n a tack.” A toast—poetry of a black subculture in which the hustler is a hero. The stanzas in “A Sound of Screaming” are Anderson’s, and in several stories, such as the gripping “Big Boy,” about a senseless, fatal razor fight between strangers—“chewing gum and grinning like a brass monkey”—Anderson inserts examples or passages of folklore as performance, barbershop entertainment. Big Boy “even knowed” and rattles off in his “high-pitched, faggity voice” “The Signifying Monkey,” the urtext of trickster ballads in black culture.

James Turner is the narrator of “Big Boy,” and James Turner is the man the woman in “Suzie Q.” is looking for. “That woman won’t built, Daddy, she was constructed.” The narrator doesn’t know James Turner, but he ends up wanting to find Turner himself in order to give back the woman he lost his job over. He took to shoplifting and got six months on the rock piles. The short piece, like others in the collection, has the atmosphere of a riff, a tale:

I opened up with an uppercut and missed. I followed up with a right and a left and two fast rights and when her defences was down I feinted and jabbed, feinted and jabbed, feinted and feinted and feinted and jabbed until wow!

Anderson, Chester Himes, and other black writers who had a disposition to sexual satire because of the tradition of male lies, were saying that primitivism and the fear of being labeled “primitive” were over. In another short tale, “Think,” James Turner fails to get a woman to play strip poker with him and a friend. “I wouldn’t give a damn ef you knowed him since Eartha Kitt was poor,” she says.

“Schooldays in North Carolina,” the longest story, has Aaron attending a segregated boarding school in the late 1930s. Founded by a white abolitionist, the school is in the white section of town, with a statue of a Confederate on a pedestal in the main square, like the small Alabama town he comes from, he says. For four years he and his roommate play the radio, talk about girls, and drink Pepsi Colas after lights out. Or Aaron dreams of being a bandleader at the Apollo or a chauffeur in Hollywood, where the movie star he opens the door for would say, “Oh Aaron, Aaron, Aaron my dearest love.” Throughout his school career, he has been courting the prettiest girl in the dining room, “prettier than Maybelle.” But his coming-of-age story has an unexpected anticlimax: upon graduation Aaron can’t express his feelings to his roommate about their friendship, and when at last he is about to be rewarded with his girlfriend’s body, he chokes.

The stories move away from the South, and in those set in an outside world the connections of the narrators to the Jessups are not stated. A man calling himself Jones remembers the “easy summer” of 1943 in “Blueplate Special.” He was working at a restaurant in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, and learning the patience needed to wait on white people, to lay the food on them real nice and keep things cozy: “To hell with it, man, you dig? I went up to Harlem and got high, and for the rest of the summer laid up in bed and played crazy. Then I got drafted.” In “Comrade,” a war story set in Würzburg in the spring of 1945, Frank talks about the poker games and the tensions on the base because he befriends a German family. When his new comrade calls to his wife, “Ich habe einen Neger mit mir,” he explains that the word so disliked by black Americans is a mispronunciation of a German word by English sailors in the seventeenth century, adding that Frank must not be offended. “‘I’ll think about it,’ I said.”

Anderson’s frame is invisible. Time passes in the way his characters talk, in the music they listen to, from victrola to jukebox, from Jimmie Lunceford to Charlie Parker. Black music is the chief repository of black idiom, Ellison argued. Hipster slang comes through town with the new music. In “Dance of the Infidels,” the bebop style of jazz lures Benevolence Delany to New York’s Pennsylvania Station after he meets Ronnie from “The Apple” in his small town:

I still couldn’t figure him out. He looked like he was in a world all his own.

“You blow?” he said.

“Blow?”

“Yeah. You play anything?”

“No. No, I don’t play nothing. You?”

“I blow box.”

“You blow what?”

“Piano.”

He sounded irritant because I couldn’t understand everything he said.

Ronnie introduces Benevolence to marijuana, Minton’s Playhouse, the Savoy Ballroom, and the poolroom where he cops heroin. Benevolence does not get high, but he observes in detail the mechanics of shooting up:

The man held the flame to the bottom of the spoon and moved it around so that it heated even. Then he threw the match away and took a hypodermic needle out of his jacket. He sucked all the melted liquid up with the needle, then handed it to Ronnie. Ronnie took it. You could hear him breathing hard.

Benevolence remembers being told in the army that one mustn’t let a man on dope pass out. He gets Ronnie back to his place, sitting with him until he is sure he’s OK: “I’m awright, Sugar.” They shake hands and Benevolence is very satisfied with Harlem.

The absence of judgment in “Dance of the Infidels” is striking. The narrator of James Baldwin’s short story “Sonny’s Blues,” first published in Partisan Review in 1957, pretends to be an algebra teacher while sounding like a mournful essay by James Baldwin on the ghetto conditions that produce heroin addicts like his brother: “He smelled funky.” He looks down on his brother’s ambition to play jazz: “Now. Who’s this Parker character?” Baldwin has given his narrator his own mediating voice, one that reassures a square audience, as if they’d read an exposé on a problem.

Lover Man ends on stories set “back home,” in a tobacco store, or listening to James Turner reminisce about his reunion with Old Man Maypeck, a character who recurs in several of the stories and is “crazier than a bow-legged coon,” with his memories of “Old Master” and the “Big War,” and his unchanging disapproval of Aaron’s father for leaving his mother. In the title story, James Turner and Old Man Maypeck are on their way to church to hear none other than James Jessup’s farewell sermon as deacon, a penitent lover who prays to look at “a chicken as a chicken and not as Sunday’s dinner.” It is in the nature of a curtain call for Anderson’s cast of characters, the return to origins as denouement.

Writers are not dialectologists. The sound of Anderson’s Deep South is a work of the imagination. He came from the Canal Zone to the Upper South, not the Black Belt, but his ear, like Hurston’s, can be faultless. An Anderson story can be in the form of a lie, and then within that lie he has a character tell a lie. Folklore as language is a collective experience, a symbol of identity, a dialect maintained by common experiences. Yet although most of Anderson’s stories are set in the South, Lover Man has considerable interest as a portrait of black postwar migration from the lusty, incestuous-feeling, small-town South to the war-changed streets of Harlem, where there is bebop and heroin and a boxer answering the door in his underwear who is maybe also rough trade.

The music of migration defined the aesthetic of the black hipster of the 1940s and 1950s. The zoot-suited figures who show up at the end of Invisible Man correspond to Anderson’s coming of age. They are the hepcats whom Claude Brown memorialized and Malcolm X had been, not marginal, but unabsorbed, nonconformist. It was an attitude. Hipsterism was for some an escape from the idea of a single authentic blackness. Clarence Major, in his Dictionary of Afro-American Slang (1970), warned that as disarming as black slang was, beneath the charm of the mode of speech lay unhappiness. People who use a code language have need of secrecy. The first person takes on the loneliness of the jazz solo.

In his sensitive afterword to Lover Man, Kinohi Nishikawa tells us that although Anderson was praised by white critics for his “perfect ear,” his “warm heart,” and the liveliness of his characters, some black critics thought his folk portraits retrograde, insufficiently political. Learning how to avoid or to appease white people is shown to be a part of a black youth’s education in Anderson’s stories. In that, they reconcile Wright’s and Hurston’s ideas of the South as both threat and home. After Brown v. Board of Education, black youth were under increasing attack. The folk feeling that some white critics found reassuring was being pushed aside by more aggressive stances. It wasn’t urban impatience rebuking southern black patience; the divide was now generational more than geographic. Henry Dumas, ten years Anderson’s junior, killed by New York City police in 1968, has in his eerie, posthumously published stories, Ark of Bones (1974), a much more retributive sense of folk culture.

Yet in the late 1950s folk wisdom was still taken as an innocence; it was undervalued in some quarters because it was seen as peculiar to black American culture, not necessarily a psychological fit with the goals of social integration. The black idiom was distant, if not hidden, from the larger society. Langston Hughes regarded the beat of Negro music and Negro speech as a private, emotional shorthand that evolved and changed in order to stay ahead of mainstream usage, of white adoption. A similar feeling runs through Amiri Baraka’s (LeRoi Jones’s) Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963), in which black culture is an avant-garde consciously shielding itself from white commercialization and contamination. Elsewhere, wise darkies were viewed as obsolete, relics of the dying order. But they survived the militant moment that had dismissed them.

It was the generation led by Toni Morrison in the 1970s that made folk culture central to the black literary experience. A black oral tradition was an alternative to the Western literary tradition, and Morrison started off by formulating a conception of the black novel as an “aural” work. Folk culture became vernacular culture; Negro dialect was elevated into Black English. Henry Louis Gates Jr. is a scholar who did not forget Anderson, citing in The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism (1988) his story “Signifying” as “a masterpiece of the genre” and “one of the most delicately wrought representations of Signifyin(g) as theme, as depicted oral ritual, but also as structuring principle.” Vernacular culture was no longer underground communication. The supposedly low was at last recognized as mainstream.

The triumph of the vernacular took a long time. After all, Negroes are telling ghost stories in Washington Irving’s Knickerbocker New York. Yet even if Anderson’s treatment of his folk material disappointed some, his storytelling gifts were undeniable. The critical success of Lover Man got him included in anthologies such as L.M. Schulman’s Come Out the Wilderness (1965), one that puts him in the select company of Wright, Baldwin, Ann Petry, Owen Dodson, and William Melvin Kelley as representatives of familiar and new voices in postwar black American literature. What happened? Nishikawa is puzzled. He finds clues in Anderson’s disastrous temperament and in his being angrily out of sync with the civil rights era.

Nishikawa traces Anderson’s steps as fully as he can. Though not a US citizen, he enlisted in 1943 and was sent to Germany and Iran, and was later in Paris studying German metaphysics. There he began to write and met Mordecai Richler, who may have pointed him toward Majorca. The White Goddess was the backpack book of its day, and Anderson turned up there in the early 1950s, perhaps in search of Robert Graves. “After the first shock of novelty, the villagers’ reaction was ‘How lucky we are! A black man!’ In Majorca negroes bring luck,” Graves wrote of the tall, soft-spoken stranger in the village.

Anderson traveled back and forth between Majorca and New York in the 1950s. Together with Terry Southern, he interviewed Nelson Algren for The Paris Review in 1955. In 1949 Algren had published The Man with the Golden Arm, in part about morphine addiction, which he explained in the interview was almost an afterthought. Anderson was at Yaddo in 1955 at the same time as Baldwin, but Nishikawa notes that his behavior offended the director, Elizabeth Ames. He refused to pay his phone bill, informing Ames that he couldn’t risk his writing life for the sake of a job just to take care of bills. When he asked for another fellowship, she demurred.

In 1955 Anderson, whether bragging or begging, wrote to Graves from New York that he’d been hanging out with juiceheads and hopheads on the waterfront and had changed his address six times. Graves came to the rescue, or at least wrote the foreword to Lover Man. What happened? The life of apricots and yogurt was easier, and Anderson must have been back on Majorca in 1962, because he and Graves had a falling out then. Graves complained of Anderson using sexually explicit language with his wife, and also of what he called Anderson’s “drinking and doping.”

For another thing, Anderson’s first novel happened. All God’s Children (1965) is a mess, a notebook of inchoate ideas about the Civil War. Anderson attempts to historicize black speech, but his ear is gone. His first-person narrator, October Pruitt, invokes “negro voices” and the “niggersmell.” Anderson’s picture of plantation life does not even bother to be realistic. The plot in turn seems improbable: October’s passionate love affair with the Old Master’s daughter, who is happily married off in the next chapter. In the course of things, October escapes North but returns South, is kidnapped, sold downriver, escapes, fights for the Union, is wounded, survives, forms an alliance with the Old Master’s heir—his childhood pal—after the war, and they run things together, until October is lynched.

Anderson inserts comic tales and folk voices, but his novel is not satire. His intention was perhaps to say that his hero was always a free man, the maker of his own destiny, an epiphany of Frederick Douglass’s: that even in bondage he could never be a slave in fact. In Anderson’s book the point is somehow obscure, abstract. The mood of the time was reflected more in Margaret Walker’s folk-filled but forward-looking Civil War novel Jubilee (1966). She said in an essay that she felt she began the novel when she heard her grandmother’s stories as a little girl.

Nishikawa observes that a novel about an enslaved man who escapes to freedom but chooses to return to bondage left people “scratching their heads.” Anderson’s bad luck is that for a black writer, to be a contrarian is usually a shrewd career move or survival tactic: George Schuyler or Zora Neale Hurston trying to make themselves matter by going against the grain on black issues. But what Anderson’s novel reveals in its disorganization is his inability to concentrate, to make one page connect with another, he who once commanded subtle code.

Nishikawa says that around the time All God’s Children was published, Anderson wrote to Graves about a suicide attempt. A letter to The New York Times in 1965 supporting William F. Buckley Jr. against James Baldwin was the last thing Anderson published. His final letter to Graves was written in 1966, after which Nishikawa can find no more documentation concerning his life. He disappeared, his whereabouts unknown before his death in New York City in 2008.*

“Lover Man.” A song written in 1941 by Jimmy Davis, Roger Ramirez, and James Sherman, famously associated with Billie Holiday, who, when she recorded “Lover Man” in 1944, was already with the man who would get her hooked on heroin. When Charlie Parker recorded his version of the song in 1946, he was so high his producer had to hold him up while he played. Anderson published Lover Man in 1959, the year Billie Holiday died. Lover Man O where can you be?

This Issue

July 20, 2023

The Trouble with Truth

None-Too-Gay Divorcées

-

*

Patrick Hill, “Robert Graves and the Mystery of Alston Anderson,” charlesmarlow.com, January 24, 2016; and Lawrence Downes, “The Three Burials of Alston Anderson,” The New York Times, June 12, 2011. See also Simon Gough, The White Goddess: An Encounter (Norwich: Galley Beggar, 2012); and Miranda Seymour, Robert Graves: Life on the Edge (Henry Holt, 1995). ↩