As the title suggests—particularly once you realize that its grandiosity is unironic—The World and All That It Holds is by some distance Aleksandar Hemon’s most ambitious work, with the main action spanning thirty-five years, two disintegrating empires, World Wars I and II, and the Russian and Chinese Revolutions. The problem is that his transparent desire to paint his masterpiece results too often in a self-conscious striving for effect and an unwavering commitment to solemnity. Anybody who comes to the book without having read his earlier ones might be surprised to hear that Hemon can be a playful, funny writer. Here, such comedy as there is proves largely inadvertent.

Granted, it’s not hard to see why Hemon might have wanted to strike out in a new direction. Since his first short story collection, The Question of Bruno (2000), his reputation has steadily and justifiably grown, with honors including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a MacArthur “genius” grant, and three titles shortlisted for a National Book Critics Circle Award. At the same time, the books themselves have shown an increasing impatience with their own subject matter, which has generally been versions of Hemon’s own admittedly extraordinary life and his attempts to make sense of it.

Hemon grew up in Sarajevo, Bosnia, when it was still part of Communist Yugoslavia. In 1992, aged twenty-seven, he was part of a journalistic exchange to the United States that was supposed to be temporary—but soon after he arrived, the Bosnian War began and his city was besieged by Serb forces for what turned out to be four years. Finding himself suddenly a refugee, Hemon settled in Chicago, working as a bike messenger, a sandwich maker, a canvasser for Greenpeace, and a seller of magazine subscriptions. He also learned English, first well enough to teach it as a second language, and then, more unusually, to publish short stories in The New Yorker that earned him comparisons to Nabokov.

Not that Hemon appeared especially keen to ingratiate himself with his new compatriots. The centerpiece of The Question of Bruno was the eighty-page “Blind Jozef Pronek and Dead Souls,” in which Pronek, a character with a biography very like his creator’s, is constantly struck by the obesity of Americans, their ignorance of geography (“Bosnia…That’s in Russia, right?”), and their unearned conviction about living in “the greatest country on earth.” Faced with all this, he discovers how easy it is for a refugee “to become someone else, a complete stranger to oneself.”

The collection also drew on Hemon’s life in Bosnia, where his great-grandparents moved from Galicia (the region that is now part of Ukraine) as the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell apart after World War I, bringing with them the beekeeping that has buzzed through all his work. Pronek then returned in Nowhere Man (2002), an overlapping group of stories in which he was seen by a series of different narrators at different stages of a life that again closely resembled Hemon’s, complete with Ukrainian ancestors, an early career in Sarajevo as a journalist, and a 1992 exchange program to the United States that leaves him exiled in Chicago.

Hemon’s first novel, The Lazarus Project (2008), looked initially like something of a departure. It opens in 1908 with the true story of the Jewish immigrant Lazarus Averbuch showing up at the home of Chicago’s police chief, George Shippy, who without much in the way of evidence decides that Averbuch is a murderous anarchist and shoots him dead. It is, however, not long before we’re back in the world of the Hemon alter ego. The aftermath of the killing is interspersed with the first-person narration of Vladimir Brik, a Bosnian-born American writer investigating the Averbuch case for a potential novel in which he’d draw on his personal experience of immigrant travails (“lousy jobs…the acquisition of language, the logistics of survival”) to animate the story. Brik also bags a lucrative scholarship similar to the “genius” grant Hemon received at about the same time and uses it, as Hemon did, to visit Eastern Europe with a photographer friend. Their first stop is Lviv, Ukraine, near the village where Brik’s beekeeping grandfather was born. Their last is Brik’s old hometown of Sarajevo, where “it occurred to me that…I would always be here, where my heart was.”

So what did Hemon do next? The answer was stick to his guns. Love and Obstacles (2009), which again took the form of overlapping stories, followed apparently the same unnamed narrator from his childhood in Sarajevo to survival in Chicago during the Bosnian War by such means as selling magazines door-to-door and on to a successful career as a writer who’d published a story called “Love and Obstacles” in The New Yorker. Along the way, we got a thirty-page tale about his Ukrainian-descended family’s love of beekeeping.

Advertisement

For my money, Love and Obstacles was Hemon’s most accomplished work up to that point: funny, rueful, and angry—often all at the same time. Yet despite the many pleasures it offered, you couldn’t help noticing how much of the material Hemon had covered before. And neither, it appears, could he. In one passage, the narrator is somewhat dismayed when, on an American book tour, he realizes “everyone was content to think that I was in constant, uninterrupted communication with the tormented soul of my homeland”; in another, he delivers to a fellow author his “usual, well-rehearsed story of displacement and writing in English”; in a third, he talks of “the image of the noble, worldly misfit who found his salvation in writing, the image I had so carefully and publicly established.”

When a filmmaker approaches the narrator to contribute to a documentary about “the Bosnian experience,” he nudges her “toward a short film in which I could play myself in various situations from my life—one of those brainy postmodern setups everybody likes so well because it has something to do with identity.” This mixture of self-satire, self-fatigue, and maybe even self-disgust is most starkly expressed when the narrator decides that “my story is boring.” On the other hand, he admits, “once you start inventing and soliloquizing, it is terribly hard to quit.” In short, Hemon seemed to sense with a distinct pang that all his books thus far could have had the same title as the one that Averbuch’s friend in The Lazarus Project dreamed of writing: The Adventures of a Clever Immigrant.

And, as we know from a recent interview, it was in 2010, the year after Love and Obstacles, that Hemon signed the contract for The World and All That It Holds. The immediate reason for the long delay in the book’s appearance was the death from a rare tumor of his one-year-old daughter, about which he wrote piercingly in an essay, “The Aquarium,” that appeared in The Book of My Lives (2013), a loose collection of autobiographical pieces confirming how heavily (if sometimes playfully) he had mined his life for his fiction. Six years later, he confirmed it all over again in My Parents: An Introduction/This Does Not Belong to You (2019), a pair of complementary memoirs published in one volume, which even its own jacket copy acknowledges is “grounded in stories lovingly polished by retelling.” Or, as Hemon rather wearily put it in the second memoir, “There are no more newly discovered memories, the repertoire is presently, eternally, woefully limited, and I’m looping through it.”

The first sign of a break for freedom came between the two autobiographical collections. The 2015 novel The Making of Zombie Wars is pretty much a flat-out comedy—if a dark one—in which Joshua Levin, a would-be screenwriter, isn’t a restless Bosnian-born exile but a contentedly American secular Jew. (Hemon himself is a gentile.) He does live in Chicago and teach English as a second language. And several of his pupils are from Bosnia, including the beautiful but married Ana, with whom he starts an affair that ends in the same type of cartoonish violence as does the Zombie Wars script he’s working on. He is also friends with a Bosnian named Bega, whom he knows from his screenwriting workshop and who at times seems like a send-up of the author. “Man is from Sarajevo. He was happy there. He was young…. War came. He is refugee now,” goes one of Bega’s movie ideas. “Yeah, yeah,” the workshop leader replies. “We heard that the last time. Got something beyond that?”

As the violence, jokes, and sex pile up, the result is definitely Hemon’s wildest book—and, I would say, his most entertaining, with much of the fun coming from the sense of a writer letting himself off the leash and relishing a newfound irresponsibility. (This January in an interview with The New York Times an apparently recovered Hemon sternly denounced Philip Roth, whose “steadfast commitment to the many privileges of male whiteness reliably repels me.” In The Making of Zombie Wars, Joshua reads Portnoy’s Complaint and, without any noticeable authorial dissent, finds it “unsparingly honest.”) Nevertheless—or maybe exactly for those reasons—you can see why even admiring reviewers called the novel a “surprising…rambunctious farce” and compared it to a “gross-out movie,” rather than greeting it the way the author’s friend David Mitchell has obligingly greeted The World and All That It Holds—as “Aleksandar Hemon’s masterpiece.”

Which brings us back to Hemon’s almost achingly responsible new book. Rafael Pinto is Jewish, too, and when the novel begins, in 1914, he is living in Sarajevo, where he works in a pharmacy inherited from his devout father. He’s also, as we soon learn, both gay and an opium addict, whose own experiences of God come mainly when he’s high on the shop’s laudanum—which by the second page he is. His ruminations on “the radiance of His majesty” are interrupted by the entry of a handsome Austrian soldier. Emboldened by the drugs, Pinto kisses him and follows him out into the street on what will turn out to be the most significant day in Sarajevo’s history.

Advertisement

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand has come up before in Hemon’s fiction. In “The Accordion,” from The Question of Bruno, the Hemon-like narrator (possibly Hemon) claims that his great-grandfather, “freshly arrived in Bosnia from Ukraine,” was holding an accordion with a missing key near the archduke when he was killed. Now, as Pinto joins the crowds in an attempt to find the handsome officer, the man holding the accordion with a missing key is back—and this time influences history by accidentally bumping aside another guy who was about to grab the assassin’s gun. As a result, “the shots rang, louder than a cannon salvo, and…the world exploded…into the before and after.”

And with that, so does Pinto’s life, as the book moves to Galicia in 1916, where he’s serving in the Austro-Hungarian army fighting the Russians—and already in love with Osman, a Muslim fellow soldier and Sarajevan, with whom he has joyous sex “in a trench, in the woods, on a haystack, in the barracks bathhouse.” Their love deepens as they become prisoners of war in Tashkent (in present-day Uzbekistan) until the Russian Revolution reaches them, their captors run away, and they escape into the city. Fortunately, Isak, the widowed doctor who takes them in, fully approves of their relationship, having been denied his own chance at gay happiness when the love of his life was beaten to death in a pogrom. “What is it that makes people do things like that?” Pinto asks after hearing the story, with the mixture of portentousness and banality that will characterize much of the book.

In an interview earlier this year, Hemon scrupulously acknowledged his “stage fright” at the “cultural appropriation” involved in imagining “a consciousness from 1914 by a queer man,” before he decided, “Fuck it. Let’s do it.” The trouble is that the initial nervousness doesn’t seem to have quite gone away, and he never really does fuck it, instead handling the relationship with a level of anxious piety that often curdles into sentimentality. At one point we hear that “Osman was already up and gone, leaving but an indentation in the reed mat on which they slept. Had he kissed him before he left, or was it part of a dream?” At another, “a pair of turtledoves in a tree branch above watched them, cooing, as in a poem.”

In the same interview, Hemon said, “I strive for complexity,” on the indisputable grounds that “everyone is complicated.” But, again, this is not a theory he wholeheartedly embraces in practice. Most obviously, it doesn’t appear to apply to Osman, with his “eyes…like mountain lakes on a sunny day,” his brilliance as a storyteller, and his all-around virtuousness that borders on the saintly. (He is, after all, “the kindest man in the world.”)

Or, in fact, a virtuousness that eventually crosses into the Christlike. For reasons that perhaps suit the plot more than the characterization, Osman apparently embraces heterosexuality long enough to impregnate Isak’s daughter Klara. While she’s in labor, the Bolsheviks are seen approaching the safe house—and bee farm—where Osman has taken her and where Pinto is assisting with the baby’s delivery. Osman volunteers to go back and intercept the Bolshevik posse despite Pinto’s fierce protests and (accurate) fear that if he does, they’ll never see each other again. So it is that Osman lays down his life to save his friends—but not before he has echoed Christ’s promise to the disciples by assuring Pinto, “I will always be with you.”

And like Christ, Osman is as good as his word. After Klara dies in childbirth, Pinto takes the baby, Rahela, with him on a six-year journey across the Taklamakan Desert toward China, during which he continues to hear Osman’s voice urging him on. Even in death, Osman doesn’t abandon his fondness for speaking in little nuggets of wisdom that bring to mind the character in E.M. Forster who “always delivered a platitude as if it was an epigram.” Back in happier times, Osman would make remarks to Pinto that a lesser man might have found a bit pretentious (“You have a soul, that’s the candle. The candle never burns itself out”), and some that an even lesser one might have considered worthy of the rejoinder “No shit, Sherlock” (“When death comes, that’s the end of life”). Posthumously, he offers such encouragement as “You’ll die when it’s time and you’ll know it’s time when it comes.”

Worse, this tendency infects the rest of the narrative. Even at times of genuine excitement, Hemon keeps pausing the action for grand-sounding pronouncements that don’t stand up to scrutiny. When Pinto escapes from the Tashkent prison, his tense journey to freedom is interrupted within the space of four sentences by both “Troubles dim your eyes, but liberty blinds you” and “The evil in this world is the leftover from the worlds destroyed.” (Would that first aphorism make any more or less sense if it were reversed: “Liberty dims your eyes, but troubles blind you”?) At another characteristic moment, Pinto and Rahela hide in a cave from a desert sandstorm—although it takes Hemon a while to tell us how they’re doing:

He who is in the dark can see what is in the light, whereas he who is in the light cannot see what is in the dark. Only the Holy One does see what is in the dark, because He sees everything, everywhere…. And if He ever bothered to actually look into this particular lightless cave, He would see Pinto and Rahela, now sleeping on his chest.

So they’re OK, then.

Indeed, that many of Hemon’s blasts of windy rhetoric are religious in nature makes for a handy comparison with The Making of Zombie Wars and offers further proof of his transition from winning mischievousness to off-putting solemnity. That novel had plenty of religious aphorisms as well, but they were invariably comic and irreverent: “I will walk with the Lord in the lands of living, and the rest of yous can go fuck yourselves”; “The Lord reviewed the whole of what he had done and, behold, he couldn’t remember a fucking thing.” In The World and All That It Holds, they’re not only delivered straight—if not always decipherably—but also repeated several times.

We’re told on three separate occasions, for example, that “For everything God created, He created its counterpart”; that “God has no needs and we are the needy ones”; and, most mystifying of all, that “Because you hear so many voices, do not imagine that there are many gods in heaven.” In The Book of My Lives, Hemon gently mocked his younger self for trying “to produce some lofty-seeming thoughts, coming up with hapless imitations instead.” Now he can unblushingly write—again three times in all, with one minor variation—“The worlds that preceded this one and were destroyed were like the sparks that scatter and die away when the blacksmith strikes the iron.”

Nobody who reads The World and All That It Holds is likely to complain about feeling shortchanged—and not just because it bristles with so many different languages.1 (This does create the desired effect of a jumble of nationalities, although the lack of translations might prove tricky for any readers a little rusty on, say, their Ladino, a variation of Spanish spoken by Sephardic Jews.) The novel is often successful as an adventure yarn, even if it would work better without the constant editorializing. To be sure, the geographical and historical settings are unfailingly vivid, proving the truth of the idea in one of Hemon’s earliest stories that “the verisimilitude of fiction is achieved by the exactness of the detail.” His sympathy with people caught up in history can be highly affecting, and there’s no denying the emotional punch of the book’s climax.

Adding to the narrative richness, meanwhile, is a large supporting cast, including a scene-stealing British spy—complete with a “stiff upper lip,” a “chin slightly upturned in perpetual contempt,” and a firm belief that Americans are “muttonheads”—who acts as a recurring deus ex machina.2 Pinto and Rahela reach Shanghai just in time for the Japanese invasion, and a memorable new villain turns up in the shape of a (muttonhead) American “committed to wishful thinking and arrogance.”

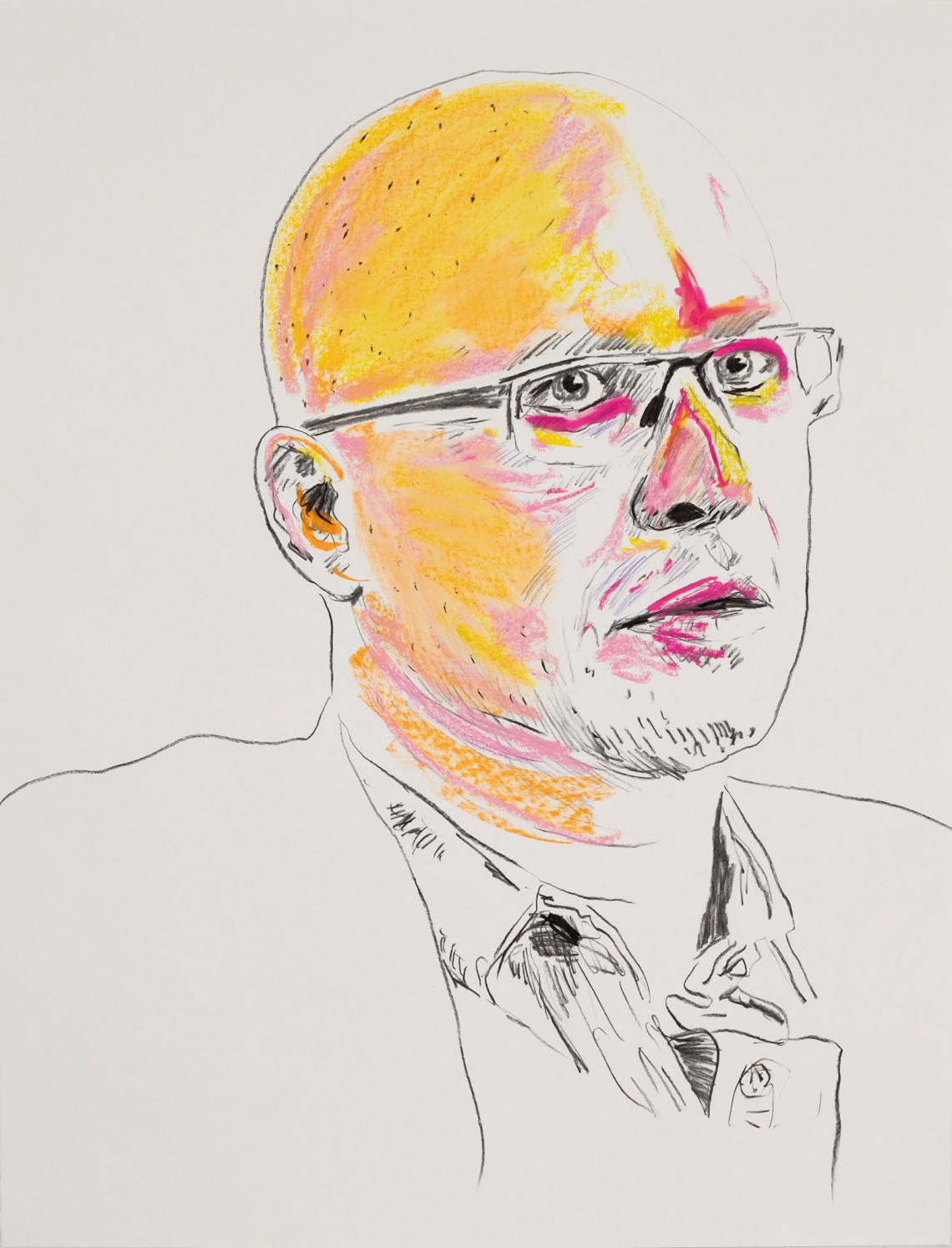

For good measure, if less happily, the book also provides the kind of coda that Hemon has used regularly since Nowhere Man, but that here smacks of “one of those brainy postmodern setups everybody likes so well.” The final chapter features the apparent self-portrait of a rookie Bosnian American writer at a 2001 literary festival in Jerusalem. There, the writer meets the now-elderly Rahela, who relates to him the basic outlines of her story, from which he’s seemingly created the novel we’ve just read. This serves to explain the “I” narrator-researcher who has shown up from time to time and whose presence, according to Hemon, is ethically necessary because in order to “write about someone who is not me…I have to acknowledge that I am imagining it”—a fact that we might have worked out for ourselves.