In 1987 Maya Angelou delivered a poetry performance to a packed theater in Lewisham, South London. The theme of the evening was love—“romantic love, agape love, sensual love, familial love, and self-love”—but also what she called “love for what might seem to be unlovable.”

Angelou was thinking of how some people felt toward their Black forebears who had suffered degradation, who had been forced to make a show of their subservience just to survive. “You all know that Black Americans for centuries were obliged to laugh when they weren’t tickled and to scratch when they didn’t itch,” she told the audience. “And those gestures have come down to us as Uncle Tomming.”

“I don’t know about any of you,” she continued, “but I wouldn’t be here this evening had those people not been successful in the humiliating employment of those humiliating ploys.”

Admiring those who resisted is easier, that is, than admiring those who submitted. But what if we understand their displays of compliance and docility as acts of love for those who have yet to come? Angelou said that evening:

When any human being is willing to allow herself or himself to be seen at the most debased level, most demeaned, most dehumanized level—thinking that by doing so he or she can ensure the survival of yet another human being, that is love. Albeit bitter, brutal, painful, that too is love.

This more demanding, less obvious, at times counterintuitive emotion both for and from those who, at first sight, may appear pitiful and pathetic can provide the potential for intergenerational dialogue, if not always devotion. This is particularly true in times of social upheaval, when the opportunities denied to one generation suddenly become available to the next. Those who came before sacrifice a great deal, including their dignity, in the hope that those who come after might have a better life. It is only when the young recognize what the privations of their elders have done for them—and the elders recognize that the young have the right to chart their own path—that the kind of intergenerational love to which Angelou referred can grow.

Sometimes that potential lies buried too deep under bitterness, shame, brutality, and trauma to ever be realized. In place of love, a pattern of rivalry and miscommunication festers, whereby elders resent the success and freedom they feel they enabled but could not themselves enjoy, while their offspring regard the past as a backward place where the indignities their ancestors experienced are evidence not of sacrifice but of pusillanimity.

This dialectic exists in all kinds of literature, from Chinua Achebe’s African Trilogy, in which each generation seeks to distance itself from the practices and traditions of the last, to Tom Segev’s The Seventh Million, which documents early Israeli attitudes toward Holocaust survivors and Jewish refugees from Europe. But it is particularly prevalent in books by migrant and minority writers; I think of Andrea Levy’s Every Light in the House Burnin’, Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, or Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones. For in recent times, it is in Black, brown, and migrant experiences that one is most likely to find parents providing opportunities for their children that they themselves did not enjoy, in the hope that their children’s lives bear as little resemblance to their own as possible.

This question of how love, aspiration, and identity is transmitted across generations and continents, of what is lost, what is distorted, and what can be salvaged and repurposed, is the central thread that runs through Colin Grant’s I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be. Grant’s parents immigrated to Britain from Jamaica in the late 1950s. He and his six siblings grew up on the Farley Hill housing estate in Luton, a medium-sized town thirty-five miles from London but culturally light-years away.

The book is structured as eight extended, overlapping vignettes from different moments in Grant’s life. They focus on people who have influenced him, most but not all of whom are from his family. The majority of them are difficult, oppositional, embittered—or all three. Grant’s family makes for interesting reading not just because it is so combative and fractious but because it dedicates so much time and energy to being so.

“Members of our family did not succumb to cancer, heart or renal failure like ‘reasonable’ people,” writes Grant, a frequent critic in these pages.

The most common form of death was murder. They died having been knifed by their own brother over an argument over washing up, or after drinking from a cocktail spiked with tiny bits of glass ground down by a vengeful lover. At least one had been shot by her husband in a dispute over an affair.

Within this melee, Grant appears less as a neutral observer than as a nonviolent combatant. When a close friendship with Charlie, a white fellow student, teeters between the platonic and the romantic only to collapse under the weight of sexual misunderstanding, Grant explodes: “What do you want from me?… A black trophy, an ornament? Add to your bona fides? Charlie? Yeah she’s right on, she’s cool. Only hangs out with black guys.” After a particularly irritating exchange with his father, he momentarily contemplates “pushing a fist into my father’s face [and] pounding it until it was a bloody mess.”

Advertisement

All this makes Grant a reliable and perspicacious, if at times irascible, guide to the characters around him. He draws them with anthropological knowing and emotional intelligence. As a narrator, he enjoys a critical distance from his subjects, straddling many worlds—professional, racial, socioeconomic, cultural—but not really embedded in any. He finds himself at best marginalized and at worst besieged.

We see Grant as a smart Black working-class boy. His father, Clinton Grant—better known as Bageye, for the large bags he has under his eyes—enrolls him in private school, explaining to the headmaster that he “didn’t want his son to suffer the shameful experiences and lack of opportunities he’d endured as a child,” and that he’ll find the money somehow. He then pays the school fees from the proceeds of small-time drug dealing. We see Grant as a medical school dropout and a journalist at the BBC, where he is constantly in trouble for displaying “aggressive” behavior. Each conflict confirms, in different ways, the strained relationships he has with most institutions he finds himself in.

At times this can be very painful. When Grant is made head boy at his private school, tradition dictates that his mother, Ethlyn, be guest of honor at the high table for the dinner and dance. She arrives in her Sunday best with Anne, an Irish friend from work. “This, after all, was at some level what she had dreamed and worked for,” writes Grant, “grabbing all the overtime at the factory she could get: a son making his way in high society; you couldn’t get higher than the high table.”

Tradition also demands that the previous head boy’s father, Mr. Jenkins, lead the dancing by inviting the new head boy’s mother to accompany him in the first waltz. But when the moment comes, Jenkins hesitates. Grant recalls, “He glanced briefly at the working-class black woman across from him, whom he was to partner; his face was flushed with uncertainty.” No hand was proffered; the tradition was not honored. Ethlyn danced with Anne instead.

Grant goes on to enroll in medical school, much to his family’s delight. Five years later, he quits, feeling he is ill-suited to the profession. When he tells his uncle Castus, a “ribald philosopher” who “acted, when solicited, as a mentor,” Castus thinks he has lost his mind: “You know how many black man would want what you have? Medicine, man! Medicine! You think I woulda walk away? You mad!” Grant’s impractical decision, Castus insists, is an indulgence that nullifies all the work people like him put in so that Grant’s generation could take advantage of the opportunities that had been denied to them. In this particular exchange lies the meaning of the book’s title. “I’m black so you can do all of those white things,” says Castus. “I’m black so you don’t have to be. It’s a full-time occupation.” Grant later joins the BBC World Service, where he becomes embroiled in a series of racially loaded confrontations with colleagues.

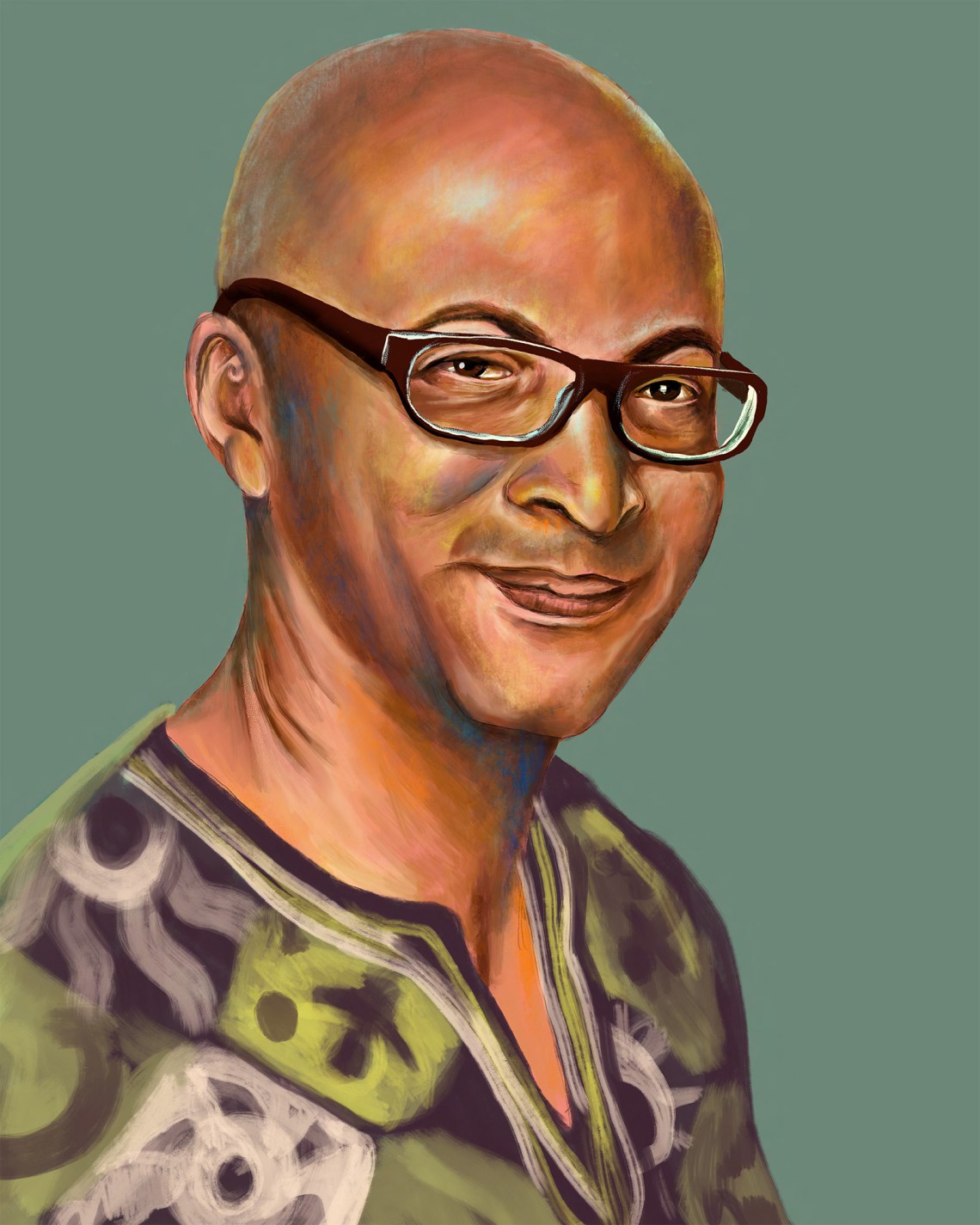

I have met Grant several times; he hardly seems like a candidate for serial office disputes. Soft-spoken and deliberate in his manner, Grant may show signs of irascibility in his prose, but there is no indication of impetuosity or malevolence in his behavior.

His time at the BBC reveals a culture of brittle, middle-class, white gentility that implodes on impact with the slightest nonwhite critique, let alone challenge. Asked for his views about creating an open-plan office, Grant says, jokingly, “that [he] didn’t like open-plan offices, because it made [him] think of plantation life, with the overseer in the big house looking over the slaves toiling in the cotton fields.” Everybody laughed, he recalls, apart from the new manager, who called him into a small office and fumed: “How dare you accuse me of wanting to be a slave owner!”

A week later, he was invited to a disciplinary hearing on the grounds that he had exhibited “a pattern of behaviour which might be regarded as aggressive [and] can be perceived as hostile, in terms of your tone of voice or body language.” In fact, Grant claims to hold “the record for the most disciplinary hearings ever brought against a BBC employee (four).” That in all four instances the allegations were found “not proven” says far more about the BBC than it does about him.

Advertisement

As a working-class person graduating into middle-class institutions, and as a Black person navigating white cultural landscapes, Grant finds himself in a constant state of arrival but never quite belonging. The farther he travels from his council estate and migrant roots, into a more elevated world of pinstripes and private clubs, the greater the challenge of finding his bearings. This is an issue less of authenticity than of learning the dialects and codes for each new social stratum he occupies. “I hadn’t stopped to consider that the BBC was still a microcosm of British society,” he says. “And that there were people inside this liberal institution who would continue to view me, a black man, with suspicion.”

The tension between Grant and Uncle Castus illustrates the classic dilemma of those on either side of a seismic generational divide, exacerbated here by immigration and social mobility. The sacrifices the elder generation made for its children do not signal an end to its humiliations, only a new venue for them. Contrary to Castus’s insistence, Grant actually still does have to be Black. And being Black still has consequences.

There is a cruel lesson here for the minority immigrant whose children will not be able to pass when they climb the class ladder: no amount of personal sacrifice by the parent or social elevation for the children can protect them from racism’s vile tentacles. You cannot earn, learn, behave, perform, or charm your way free of it. The parent’s investment is one of graft and humiliation. And the best return they can get is children who are better equipped to withstand it.

While each of Grant’s chapters focuses on a character and a moment, there is one person who haunts the memoir throughout: Bageye. Bageye is in many ways the nucleus not only of this book, but of most of Grant’s autobiographical work. (This is Grant’s sixth book; his third, Bageye at the Wheel, is about his father.) He is the epicenter of Grant’s childhood anxieties.

Grant evokes an atmosphere of petulant menace emanating from his father, which still troubles him. “My father was always a difficult man to read,” he writes. He depicts Bageye as a feckless gambler and domestic tyrant, a man “in a continual foul mood that was never ameliorated, in our presence at least, and possessing an unnerving combustibility.”

Bageye was violent and abusive. He threw Grant’s mother, Ethlyn, down the stairs, broke a flowerpot over her head, and tossed a pan of boiling water at her. As a child, Grant feared him. In later life, that fear curdled into resentment and loathing. But as the book progresses, Grant recognizes that Bageye has assumed an outsize role in his adult imagination that cannot be squared with the man he encounters many years later. Gradually we see him come to terms with his father not as a metaphor but as a man.

Grant lost contact with Bageye in his midteens, after his mother kicked his father out of the house. He didn’t see Bageye again for thirty-two years, estranged by his father’s abuse. He reestablished contact because he needed Bageye to sign off on the manuscript of Bageye at the Wheel for legal reasons. His father, by then in his eighties, was not difficult to find. Grant just called the West Indian pub, the Chequers, in his hometown of Luton, where Bageye had been a regular. He was still there.

By this time Grant had moved on, first to London and then to the seaside town of Brighton, where he built a family of his own. The Bageye he meets is a diminished, if still embittered, version of his former self. He instills more pity than fear.

“What do you do,” asks Grant,

when your father, whom you’ve built up as a monster, turns out to have been a straw man, a fragile figure, a candidate for compassion, a terroriser who subsequently appears to be—how can I say this delicately—pathetic?

Grant doesn’t go on to convey much compassion. But the reader does gradually begin to see Bageye, through his son’s eyes, as a complex kind of monster, with human flaws and relatively few options.

Perhaps the first step in Angelou’s appeal to show “love for what might seem unlovable,” then, is to fathom how those elders who appear at best remote and at worst ruined expressed their love and handled their hardships. Grant describes the many times Bageye was stopped by police while on his drug runs. He would see his father put on a show of excessive deference and self-mockery, inflating the man who pulled him over, then prostrating himself before him: “The bobby on the beat became ‘Detective Inspector, Sir’ or ‘Chief Constable, Sir’—all said with a theatrical flair and an exaggeratedly respectful bow.” The policeman would wave them on, but the younger Grant would be left feeling humiliated. “It seemed embarrassing to see my father yet again subjugated in front of a white man,” he writes. “But when I asked him what it all meant, he said, ‘Sometimes you have to play fool fi ketch wise.’” In other words, the smartest thing to do, sometimes, is make them think you’re stupid.

This is what his father went through to get his son the best education he could. Indeed, Bageye’s ambitions for his children at times seem inversely proportional to the low regard in which he held himself. When Grant’s sister uses a phrase Bageye thinks uncouth, he asks her, “Why you have to talk so? Why? Tell me why. Why I send you go private school, work double shift, all for you to end up speak like me? Me, who don’t even pass worms.”

An economic migrant does not just possess ambition—he or she embodies it. Migrants move in order to better themselves; they migrate with the future in mind. But for all that might be gained on the journey, much is also lost. Tales of postcolonial migration are full of examples of downward mobility, as the middle-class voyagers from the colonies find themselves reduced to semiskilled, low-status workers in the metropole.

Thinking of his father in the Chequers in Luton, Grant wonders, “Why, after venturing four thousand miles from their cinnamon-scented islands, had these pioneers settled for a regular seat at a West Indian pub with Guinness on tap…?” The answer, uncomfortable as it may be, is that this was the price they paid both for their own ambition and to get their children through the system.

This decline in status is most evident in Ethlyn. She grew up in Jamaica light-skinned and privileged, in a home with domestic help. She traded this in 1959, aged twenty-six, for the housing estate in Farley Hill and for shift work in the mother country. The trade was neither conscious nor deliberate. Ethlyn had originally planned to go to New York. An aunt in Harlem was to be her sponsor. But the trip was “vengefully cancelled” following a family feud. England was the consolation prize.

The England projected to the colonies was the land of Shakespeare and the mother of parliaments, not council houses and shift work. When Ethlyn left, Jamaica was still a colony, and island life was in many ways conservative and parochial. She recalls how, when she reached adolescence, her father took her into the dining room, tapped the sandalwood table, and declared of any future suitor, “Nothing darker than that. I don’t want you bringing anyone to this house darker than that.” By the time she left she already had a two-year-old child by Bageye, a merchant seaman she had met in Jamaica and who arrived in England shortly before her.

In the late 1980s, as part of a BBC radio documentary, Grant takes her back to Jamaica for the first time since her departure for England. There he sees her confidence return. “Listening to the ease with which Ethlyn talked was remarkable,” he writes. In Luton she would hand over the receiver rather than deal with English people who could not or would not make out her accent. “Now she spoke freely.”

The son witnesses his mother flourish and flirt her way around Jamaica, infused with a renewed, joyful sense of self. He sees her cry in the departure lounge before boarding the plane back to England and asks if she is not looking forward to her return. “To be honest…no,” she says. “There’s not much fond memories of England, we’ve got to be honest with ourselves, you know. Not much happiness, really; real happiness.”

Today, with a prime minister and home secretary of Asian descent and a foreign secretary and trade secretary of African descent, Britain likes to celebrate its multicultural achievements, as though they emerged, fully-formed, from a tradition of decency and fair play. In fact, they are the consequence of significant sacrifice from those, like Bageye and Ethlyn, who could least afford it. Grant shows not only where the burden fell to get us where we are, and how far there is still to go, but how much love was lost along the way.