Earlier this year Aubrey Plaza, of White Lotus and Parks and Recreation fame, appeared in a commercial seemingly tailor-made for her deadpan, discomfiting comedic style. She was shown walking through the woods, dressed in an appropriately outdoorsy ensemble of plaid shirt, vest, and jeans tucked into sassy, shearling-style boots. “You know me as an actress,” she said, gazing coolly into the camera. “But I’m also the co-founder of Wood Milk, the world’s first and only milk made from wood.” She recounted the company’s origin story: “Wood Milk started with a simple idea: I saw a tree, and I asked myself, Can I drink this?” The answer, she said, was yes, “if you make it into milk”—that is, something “squished into a slime that’s legal to sell.”

She took a long swig from a glass of her pulpy “slime” and emerged with a classic “Got Milk?” mustache. At last Plaza made the spoof plain. “Is wood milk real?” she asked. “Absolutely not. Only real milk is real.”

The hundred-second spot was produced by a dairy industry marketing operation called the Milk Processor Education Program, or, more jauntily, MilkPEP, the same group behind the Got Milk? campaign that became one of the most ubiquitous and influential advertisements in history. Like its predecessor, it seeks to make cow’s milk, an old-fashioned kitchen staple, feel hip and relevant again, this time by mocking the proliferating plant-derived milk alternatives that the dairy industry tried—and failed—to block from being called “milk.” Milk from oats, rice, soybeans, almonds, or cashews? Why, you might as well try to squeeze milk from a log!

But if MilkPEP had hoped that a few clever pitches might induce the under-thirty-five cohort to give “real” milk a try, the signs are not promising. The reaction on social media to Plaza’s “wood milk” routine was overwhelmingly negative. Her fans asked why she was shilling for Big Dairy. Didn’t she realize the tremendous harm the industry wreaks on the environment, public health, and animal welfare? The flood of outrage prompted Plaza to turn off the comments on her Instagram account.

Nor does anyone or anything seem capable of stemming the decline among all Americans in the consumption of cow’s milk, a trend that, surprisingly enough, started almost eight decades ago. According to the US Department of Agriculture, the peak milk year was 1945, when Americans drank an average of forty-five gallons apiece. By 2001 the nation’s per capita milk intake had been cut in half, to twenty-three gallons, and in 2021 the figure was down to just sixteen gallons of milk per person, or 5.6 ounces a day, which is barely enough to buoy a bowl of Cheerios.

Leading the ongoing drop-off are members of Generation Z: people born after 1996 drank 20 percent less cow’s milk last year than the national average. Among the eco-conscious, antipathy toward dairy milk is great enough that some high-end coffee shops feel no obligation to offer it at all. Not long ago, when I ordered a café au lait in downtown Washington, I was told my lait choices were oat, soy, or almond. “I’ll take regular whole milk,” I said. “Sorry, we don’t have that,” the barista replied. “OK, then, 2 percent,” I said. “We don’t have that either,” the barista said. “Skim milk?” “No.” “Half-and-half?” “No.” “What is this, the cheese shop in Monty Python?” I asked irritably, referring to the classic 1972 skit about a fancy cheese shop that has no cheeses in stock, which likely predated the barista’s birth by at least a quarter of a century. “Perhaps you’d like your café au lait black,” the barista said.

I should confess that I have always loved milk. I grew up drinking cow’s milk in a household where running out of it was considered an emergency on par with reaching the last square of toilet paper. In recent years I have tried to be a good citizen by purchasing only organic milk squeezed from the udders of 100 percent grass-fed cows, but the thought of giving up dairy milk entirely feels too extreme and frankly depressing. Were all those years of believing in the healthfulness, simplicity, and purity of fresh, sweet cow’s milk a farce? Doesn’t milk do a body good, at least the bony parts?

In Spoiled, a sharply written, wide-ranging, and instructive look at the history of dairy milk, Anne Mendelson, a culinary scholar, makes the case that, yes, all those years of lacto-genuflection were something of a farce. Fresh cow’s milk, she argues, should never have attained the status of kitchen essential or universal beverage in the first place. It is tricky to produce and difficult to store. It is heavy, bulky, and expensive to transport. It spoils easily. Moreover, the majority of the world’s population can’t digest it past childhood.

Advertisement

The much-ballyhooed genetic trait that allows some individuals to break down milk sugars throughout life—and thus avoid the bloating, belching, diarrhea, nausea, and other symptoms of lactose intolerance—turns out to be relatively rare, found in maybe a third of the population. But there is a notable exception. Among people of Northwestern European ancestry, three quarters or more are able to digest lactose. And because Northwestern Europeans happened to assume as much cultural, economic, and scientific power as they did in the modern era, the ability to guzzle fresh milk with little or no distress was deemed the species norm—a basic part of being human.

From the fundamental misconception of our shared capacity to digest milk arose the conviction among a roster of influential doctors, public health officials, educators, and marketers that if we can drink milk, we should drink milk, indeed we must drink milk. Children and teenagers needed milk—three or more glasses a day. Soldiers needed milk, for endurance, strength, and a taste of home. Nursing mothers needed milk; how else could they make milk of their own? Retirees needed milk—those brittle bones! Before long the government was helping to build the necessary infrastructure for large-scale distribution and enacting policies that would lure people into the dairy business. But the new dairy farmers soon learned a sobering truth. For milk to be an indispensable staple, found in every kitchen, lunchroom, and canteen across the land, it had to be cheap.

“Commercially produced drinking-milk has always been bound up with impossible dreams,” Mendelson writes.

Hailed in the late nineteenth century as an unprecedented moneymaking opportunity for farmers, it no sooner started flowing from country to city on something like an industrial scale than it faced unrelenting downward pressures on retail prices.

This pressure “turned dairying into financial ruin for numberless farmers in the twentieth century and continues to do so today.” Yet for all the retrenchment and bankruptcies, the milk business in the US remains huge, valued at about $40 billion a year, and like the tobacco industry it is ever seeking new markets, including a big push to transform China into a nation of milk drinkers, despite the high prevalence there of lactose intolerance.

Mammalian milk is a product of stupefying complexity, at least as biochemically elaborate and dynamic as blood. It contains the many hundreds of fats, proteins, sugars, vitamins, and minerals that young animals need, some of them dissolved in milk’s watery base, others packaged into tiny globules that disperse light in every direction and so make milk appear white. The ratios of those ingredients differ markedly from one mammal to another, reflecting each species’ particular demands. “For the young of herd animals that evolved to range across grassy terrain ahead of predators, it is vital to reach something close to adult size and stamina between spring and the end of the grass season,” Mendelson writes. “Their mother’s milk logically enough contains large amounts of protein.” The milk of marine mammals like seals and walruses is extremely fatty, to help build a pup’s insulating blubber, while the milk of armadillos is chalky with calcium, an element essential to the formation of the animal’s body armor.

Human milk is comparatively low in protein, middling in milkfats, and high in milk sugars, a mix that researchers believe is ideally suited to an infant with a slow-growing body and rapidly developing brain. Much about milk chemistry remains a mystery, however, and scientists have yet to design the perfect substitute for human milk. Infants can’t digest the high concentrations of proteins and minerals in cow’s milk until they are about one year old (drinking it sooner can result in intestinal bleeding and malnourishment). Today’s infant formulas are yeomanly constructs of casein and whey proteins extracted from cow’s milk or plant proteins taken from soybeans; vegetable, fish, or egg oils to provide the fats; carbohydrates from milk sugars and sometimes corn syrup; vitamins and minerals, of course; and often a tincture of mother’s guilt, from the person who knows “breast is best” but has to work or sleep or otherwise can’t do it so please leave her alone.

Mendelson points out that once a newborn has latched on to breast or teat, the link between a nursing mother and her offspring becomes a tightly closed operation. “No mammal’s milk is designed to enter the outside world,” she writes. “The complementary gateways formed by the mother’s nipple and the suckling infant’s mouth allow the living fluid to travel straight from mammary system to digestive system with no detours.” As a result, the baby consumes a liquid meal with components intact and a minimum of microbial activity. But should the milk be “diverted into an external environment”—say, a metal bucket—“its intricate structure instantly comes up against foreign agents.”

Advertisement

Ambient bacteria are particularly drawn to milk sugars, and that attraction, Mendelson argues, has played an important part in the history of dairy. Lactose is a double sugar, and its intertwined strands of galactose and glucose must be cleaved apart before a mammal can put the sugars to use. In young mammals, a liver enzyme called lactase performs the severance, but that enzyme gradually shuts down after weaning. If it did not, adult animals might compete with helpless young for access to the maternal milk bank.

There is no limit to the enzymatic genius of bacteria, however, and Mendelson writes that “from the first prehistoric days of dairying in the Near East and western Asia,” where domestication began, one group of microbes, the lactic acid bacteria, proved humanity’s “invisible allies.” The bacteria cut a bargain with aspiring dairy farmers: you give us a pail of fresh cow, goat, or sheep milk, we’ll break down the lactose you can’t digest and claim most of its sugary energy, and in return we’ll leave you with a flocculated pudding of milkfats, proteins, casein, curds, and whey that is not only nutritious and calorically dense but laced with enough lactic acid—the byproduct of fermentation—to help keep other, more dangerous pathogens at bay. True, fermented milk products like yogurt, kefir, and koumiss, having lost most of their sugars to bacterial appetites, taste sour rather than sweet, but so, too, does another product of fermentation—wine.

Sheep, goats, and horses had their place among early milking communities, but cows eventually became the preferred dairy animal. Not only did their large size translate into comparatively generous quantities of milk, but as Neolithic pastoralists gradually made their way into Central and Northern Europe, their cattle carried an innate protection against cold weather: the heat generated by the cows’ ruminant stomach. Moreover, because cows, unlike sheep and most goats, sometimes give birth and lactate out of season, a farmer with even a small herd might end up with a milk spigot for much of the year.

Another trait that traveled northward arose in the dairy farmers themselves: the genetic “quirk,” as Mendelson calls it, of lactase persistence—a version of the milk-digesting enzyme that remains more or less active for life. This polymorphism is thought to have arisen somewhere in eastern Central Europe, perhaps as recently as 2300 BC or even later. The genetic variant was not unique. “A handful of similar polymorphisms involving lactase persistence exist elsewhere in the Old World,” she writes, including among people who prefer fermented milk to fresh. What distinguished the Northern European variant was its appearance in a population that eventually set the scientific and nutritional agenda for the rest of the world.

The vogue for fresh milk began not with farmers, who rarely romanticized the products of difficult agrarian labor, but among the elites. The seventeenth-century diarist Samuel Pepys extolled the taste of “new milk,” which he and his wife would drink by the tankard while eating tarts with fresh curds. Pepys’s records also reveal a degree of lactose intolerance. In July 1666 he wrote that after “drinking a great deale of milke,” he began to “breake abundance of wind behind” and “was in mighty pain all night long,” alternately defecating and vomiting. But was it the milk, Pepys wondered, or the pints of beer that preceded it?

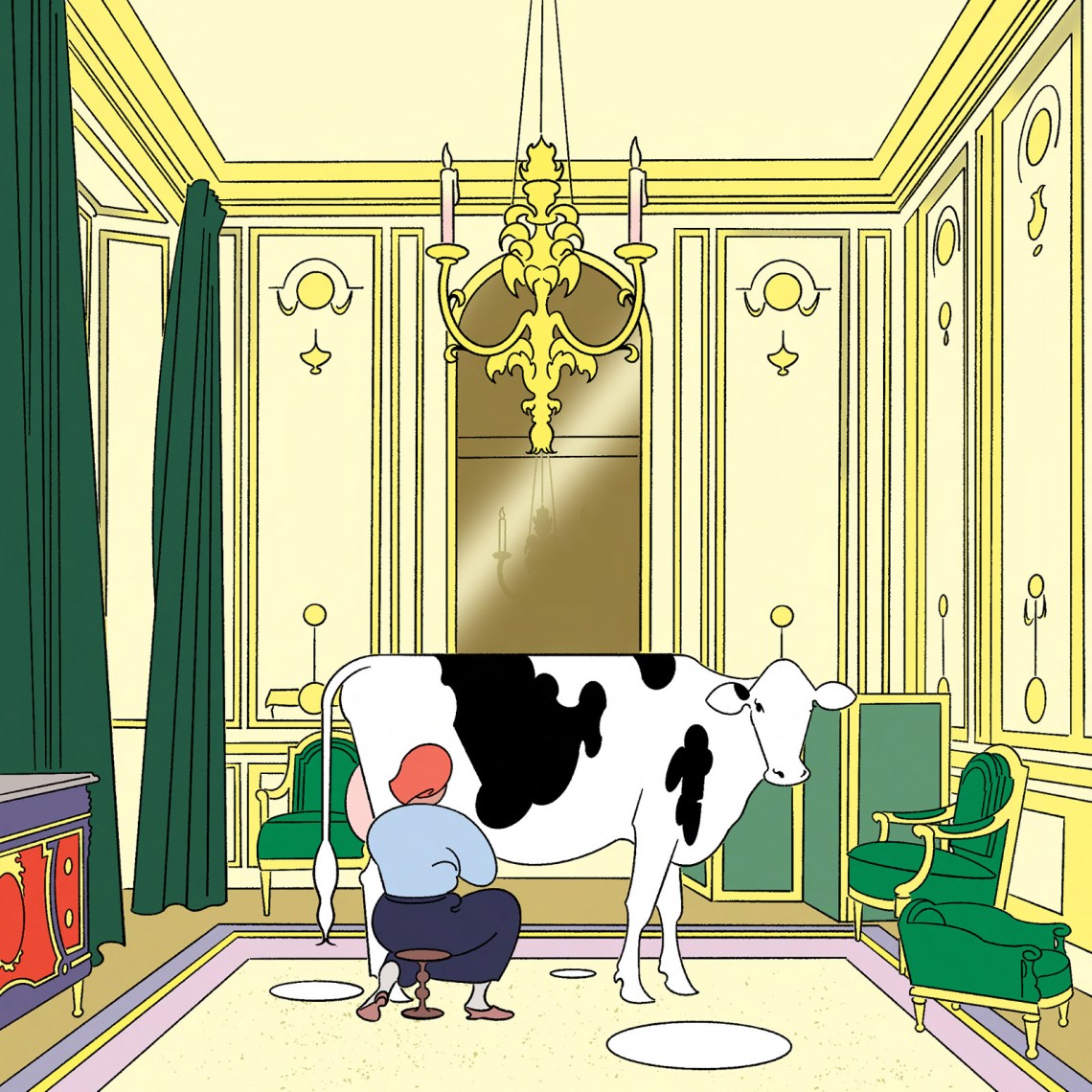

“The occasional digestive contretemps notwithstanding,” Mendelson writes, the desire for fresh milk intensified in eighteenth-century Europe, “with an upper-crust (and sometimes royal) fan club leading the way.” Marie Antoinette ordered the construction of her own “elegantly appointed” dairy, with cows and milkmaids housed in airy palaces of tile and marble. The English nobility added “ornamental dairies” or “pleasure dairies” to their estates. (Later, rich North Americans, including the Astor family of New York, did the same.) Drinking milk was now associated with wealth and privilege. The next step was to win the imprimatur of the health care profession.

It was not a hard sell. The burgeoning popularity of fresh cow’s milk happened to coincide with the Romantic-era cult of the child and the budding discipline of pediatrics. For doctors who cared for children, nothing seemed more natural than to recommend milk as a nutritional mainstay from weaning through adolescence and beyond. Cow’s milk attained “a uniquely exalted status as a life-giving proxy for mother’s milk,” Mendelson says, “a concept not closely related to any nutritional reality.” Moreover, doctors were suspicious of acidic foods and insisted that “milk should reach tender juvenile systems only while perfectly ‘sweet’ and uncorrupted.”

The medical injunction in favor of sweet milk and lots of it proved the opposite of salubrious. As the distance between cows and consumers widened, and in the absence of any protocols to protect public health, the boom in the milk trade spurred the spread of disease. Farmers and farmhands racing to get their fragile product to market before it spoiled ended up introducing into the milk pathogens responsible for diphtheria, typhoid fever, scarlet fever, and the like—microorganisms that the lactic acid of fermentation might well have helped suppress. Dairies that arose in the nineteenth century in cities like New York and London to serve the local working class were more pestilent still. Cows were fed swill from nearby breweries, and workers bearing milk pails sloshed freely through the muck.

By the turn of the twentieth century, researchers were well aware that contaminated cow’s milk was a significant source of childhood death and disease, and the push for purification began. Though Louis Pasteur invented his eponymous heating process in the 1860s to deactivate unwanted microbes in wine, pasteurization would soon be more familiarly associated with dairy. Among the most zealous apostles of milk pasteurization was Nathan Straus, “the co-owner of Macy’s department store and a man with a taste for righteous causes.” Straus believed that all children deserved a year-round supply of sweet milk, and he saw pasteurization, in which milk is heated but not boiled, as the key to sanitizing the beverage without destroying its palatability. He opened depots that sold pasteurized milk, first in New York City, then branching out to dozens of cities nationwide. He gathered statistics showing a steady drop in infant deaths among New York City’s poor after his first milk depot was founded on the East River in 1893.

There were critics of milk pasteurization and of Straus’s claims. Some argued that the heating process destroyed or diminished many of milk’s nutrients. Others considered pasteurization camouflage for filthy handling practices and said it didn’t always work as advertised, but instead left some of the most dangerous milk microbes. Critics insisted that a far more effective public health measure would be to enforce strict cleanliness procedures and subject milk samples to frequent microbial counts. Pasteurization proponents eventually prevailed, in part by declaring, as Straus did, that of course they always started with clean milk collected under hygienic conditions; pasteurization simply provided the good husbandry seal of approval to salve public fears.

Big cities began mandating milk pasteurization. In New York City, the rate of pasteurization jumped from 5 percent in 1903 to 88 percent in 1916. Smaller cities soon followed suit, the rate of milk-borne disease outbreaks declined, and nothing could slow “the breakneck expansion of the drinking-milk industry.” Straus was hailed as a hero, a saint. In Mendelson’s view, that’s like applauding a man for no longer beating his wife:

Straus and milk pasteurization saved vast numbers of lives that wouldn’t have been endangered in the first place if a long succession of influential authorities hadn’t decreed that fresh cow’s milk was an unquestionable necessity for children.

Over the years, technology and the pitiless demands of the market have shaped every feature of a dairy cow’s unenviable life. Where once there were multiple breeds to choose from and admire—“dainty” Jerseys, “refined” Guernseys, “strapping” Holsteins, Ayrshires, Brown Swiss—the Holstein cow now reigns supreme. “Many people today have never seen even a cartoon image of a dairy cow without the characteristic Holstein black and white markings,” Mendelson writes. The reason is simple: Holsteins give the most milk, and through selective breeding and calculated feeding, their initial advantage has been magnified to staggering proportions. In 1950 the average cow in the United States produced 5,314 pounds of milk per year. By 2019 that annual output had more than quadrupled, to 23,400 pounds.

The most lactationally prolific cows teeter on the edge of negative energy balance, in which they burn more calories making milk than they can take in by eating—a potentially hazardous state that can lead to sepsis, liver damage, and death. Their bulging udders are prone to painful mastitis. Bulls have been eliminated from the scene, cows are inseminated artificially, and their calves are taken from them at an earlier stage than are the offspring of beef cows. In accordance with former secretary of agriculture Sonny Perdue’s blunt observation to reporters at the World Dairy Expo in Wisconsin in 2019 that “in America, the big get bigger and the small go out,” dairy farms have been forced to consolidate into ever-larger operations of 5,000 cows or more, with some foreseeing herds of 25,000 to 30,000 animals. Even organic dairy farms that target the niche market of well-to-do do-gooders are having trouble staying solvent, and many are trading independence for an alliance with big organic players.

Milk, too, has been relentlessly refashioned to streamline production and fit market demands, real or imagined. It has been homogenized: heated and pumped through a fine sieve to break the milkfats into tiny particles that disperse uniformly through the watery medium—good-bye to the storybook sight of cream floating atop liquid in a newly delivered bottle of milk, hello standardized injections of milkfats to precisely distinguish “whole” milk from low-fat from one percent from skim. As the presumed dietary centerpiece of childhood, milk has been fortified with vitamins to help prevent childhood scourges like rickets and blindness. For the lactose intolerant, there is lactose-free milk. For those who have trouble digesting the “A1” component of milk’s casein proteins, there is a designer milk called A2. And for those who would prefer yogurt to milk, the dairy and food industries are happy to oblige, giving us Greek yogurt, French yogurt, Icelandic yogurt, Australian yogurt, frozen yogurt, drinkable yogurt, probiotic yogurt, and yogurt that tastes like a slice of Boston cream pie.

All the while, many of the putative nutritional benefits of drinking milk by the quartful remain unproven. Does milk help keep bones from thinning and splintering with age? A 2012 summary of epidemiological data from sixty-three countries showed that hip fractures are highest in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Austria—nations with long histories of milk drinking and large percentages of people with lactase persistence into adulthood. Another study found that Norwegians born in Norway had a fivefold greater risk of hip fractures than did people living in Norway who had been born in Central and Southeast Asia, where milk drinking is uncommon.

A meta-analysis published in 2022, which analyzed twenty studies covering more than half a million participants worldwide, concluded that “higher milk consumption is not associated with fracture risk reduction and should not be recommended for fracture prevention.” Still other studies have shown modest benefits to bone health from eating dairy, especially for men—who, wouldn’t you know it, have comparatively denser bones to begin with. In sum, our understanding of bone metabolism and the dynamic between calcium intake and calcium absorption remains sketchy at best, and assumptions that milk invariably strengthens bones, Mendelson says, “clearly need some adjustment.”

Plant milk substitutes are not without problems. Almonds and rice are notoriously water-intensive crops, and millions of acres of Amazonian rainforest have been cleared to grow soybeans. Mendelson observes that the need for any sort of “chilled semi-flavorless white liquid” to pour over cereal or into a cup of coffee is a matter of habit, the result of our long-held addiction to milk, and when consumers demand that such plant milk be as cheap as dairy milk, the impact on the environment worsens accordingly. Nevertheless, by virtually every metric—land use, water use, greenhouse gas emissions, and the growth of choking algal blooms—the footprint of dairy milk out-Yetis the plant pretenders.

Today there are about 9.4 million dairy cows in this country, generating more than 25 billion gallons of milk per year. If much of this staggering output is the consequence of a misguided belief in the virtue and necessity of lifelong milk consumption, and if our kids don’t want to drink milk, and if many immigrant communities don’t want to drink milk, and if adults generally would prefer a seltzer, beer, or oat-milk latte, then a reckoning is surely in store to wipe the mustache off our face.