In 1959 the guitarist Chuck Berry plucked a young girl off the streets of Ciudad Juárez, the Mexican town across the border from El Paso, Texas. Janice Escalanti was fourteen and had been making money as a sex worker. Berry later claimed that he had pitied Escalanti and wanted to help her, offering her a job as a hatcheck assistant at the nightclub he had recently opened in his hometown of St. Louis. Had it ended there, everybody involved would have been saved a lot of trouble. Instead, Berry, by now a rich and successful musician, had become infatuated with Escalanti. If she wanted to take the job, he told her, she needed to leave town with him and his musicians that same night, and after five more one-night gigs, they would all return together to St. Louis.

Berry fixed it so that Escalanti and he shared hotel rooms. They slept together, then Escalanti was perturbed to see Berry bring two other girls back to their hotel one evening and disappear with them into another room. Once they reached St. Louis and Escalanti started working at Berry’s Club Bandstand, the hatcheck counter didn’t suit her, so she started mingling with the customers. Fights ensued, she got fired, and Berry dragged her to the Greyhound bus station, where he tried to put her on a coach back to El Paso. But later that night she turned up again at the club. More angry words followed, and a few days before Christmas Escalanti and Berry found themselves on the sidewalk in front of Club Bandstand, in the early hours of the morning, under arrest and explaining themselves to a police officer.

RJ Smith ends chapter 10 of his new biography of Berry on a cliff-hanger, with Berry and Escalanti on their way to the police station, then opens his next chapter with a disclaimer. “The work and life under examination in the last years of the 1950s,” he writes, “present a challenge to the biographer, and possibly to the reader.” But Berry’s moral transgressions don’t come as a complete surprise. Rock and jazz biographies are packed with tales of on-the-road licentiousness. Berry had his fair share of such encounters. (His wife is noticeably absent from the book.) Following a show earlier in 1959 for an officers’ club at a former army barracks in the South, a young girl was seen running from Berry’s dressing room in distress. A year before that, Berry was arrested in Virginia by an off-duty police officer after he was caught peering over the partition of a women’s bathroom.

Once Escalanti enters the story, we understand that his bad behavior had become habitual. Berry ended up serving twenty months in prison for violating the Mann Act, which outlawed the transportation of women over state lines “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” But he failed to learn from the experience and continued his pattern of appalling and exploitative treatment of women, leading to lawsuits, arrests, and scandals in the 1980s and 1990s.

Berry died in 2017 with his reputation paradoxically in the ascendant and in the sewer. In death he was hailed as not merely a rock-and-roll pioneer. No, Berry was the king of rock and roll, the man who had left 1950s popular music all shook up with a procession of hit records like “Maybellene,” “Too Much Monkey Business,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” and “Johnny B. Goode.” Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Elvis Presley had all needed to take the measure of Berry before they could create their own styles. After he died, that legacy needed to be weighed against his escalating patterns of abusive and criminal behavior.

Born Charles Berry in 1926—“Chuck” was used by mistake in 1955 after he recorded “Maybellene,” his first hit, and the nickname stuck—he became the source of so many fresh ideas because everything that American popular music had been, from Louis Armstrong to Muddy Waters, was transformed when it flowed through him. He absorbed the lessons of the electric guitarist Charlie Christian, whose crisp, sparkling swing guitar style in the small groups of Benny Goodman anticipated the rhythmic labyrinths of bebop. Berry discerned from the saxophonist Louis Jordan’s band Tympany Five—the best-selling American popular music group of the time—that boogie-woogie, hitherto a piano style, could be made to work on guitar. He worshiped Jordan’s guitarist, Carl Hogan, and loved the rhythmic push and pull that resulted as the regular groove of boogie-woogie crisscrossed the syncopated swing feel of the drummer. Berry’s guitar intro to “Johnny B. Goode” reprises a Hogan lick from 1946—a grateful hat-tip a decade on.

Berry picked up his first lessons in the blues from “Confessin’ the Blues” by the Jay McShann Orchestra—sung by Walter Brown—which he committed to memory from repeated listening on a jukebox; the blues singer and guitarist T-Bone Walker was another crucial early influence. Berry found the honeyed tone of Nat King Cole’s voice and the precision of his diction entrancing—not an obvious point of connection perhaps, but he went as far as to describe Cole as his “first inspiration”; later he channeled Cole whenever he wanted to sound unruffled and suave. The Black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, who was much loved by Berry’s parents, shaped his feel for words and lyrics. As Berry began his recording career, Black musicians around him, like John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters, were unapologetic blues artists, but what exactly was the music that Berry played?

Advertisement

Smith skillfully and cannily calibrates his subject’s instinct for crossing the line: the musical possibilities created when Berry dismissed often arbitrary aesthetic boundaries are contrasted with the disastrous consequences, and harm caused, when he believed that sexual morality and decency didn’t apply to him. “Maybellene”—recorded at the legendary Chess Studios in Chicago—was a prime example of musical transgression, a song that gleefully upended expectations and attained popularity among both Black and white audiences. Berry, with his producer Phil Chess, had organized the single with near-scientific meticulousness to achieve that very goal, creating a number that “was neither Black like an Ike Turner record nor white like a Hank Williams one.” The song opened with a rhythmic strut that rolled out of hillbilly country music. Then it rocked with a rhythmic itch that borrowed from boogie-woogie. Berry’s guitar playing proudly displayed his roots in jazz and blues, one mode of thinking refracted through the other. “Maybellene” offered a sound that had not existed.

A Black recording artist embracing country music, Smith explains, was untested, and concerns were raised at Chess that “Maybellene” might be too rural to impress a hard-bitten urban audience in Chicago. But Smith shows that Berry found the music he wanted to create as far back as his schooldays. As a ten-year-old on his lunch break, he enjoyed hanging out at the local sandwich shop, as much for the jukebox as for the food. Music by Count Basie (“One O’Clock Jump”), Tommy Dorsey (“Boogie Woogie”), and Glenn Miller (“In the Mood”) captured his imagination, a random selection of records with one factor in common—they contain riffs repeated over basic blues and boogie-woogie forms.

Berry’s dream of creating music that could spread his youthful vision—of “diverse bodies filling a floor in sync with a beat”—beyond St. Louis was born during those lunch breaks. What Smith calls “the low-end hum of a piano player’s left hand” had a Proustian effect, reconnecting Berry with everything he considered important in life: with the delirious energy of boogie, with that alluring smell of onions frying on the sandwich-shop grill, with the dance of attractive bodies moving in time to the music, with his intuition that this music hinted at a grander world.

Smith, who asserts that the multiethnic audience Berry developed “would increasingly tilt white as he conquered America,” investigates where he gained the confidence to think he could question—even transcend—the racial boundaries that so many were determined to maintain. Again, the seeds of this self-belief were planted in his earliest years. Berry was raised in a Black neighborhood of St. Louis known as the Ville, which had existed since before the Civil War. The people living there considered themselves separate from the poorer Black areas of the city. Grace Bumbry, Tina Turner, Bobby McFerrin, and Lester Bowie also grew up in the Ville; Miles Davis was raised nearby.

The church, the dominant influence on the lives of many of his peers, passed Berry by entirely. Boogie had entered his soul and there was simply no space left for religion. He made a conscious decision not to let sin weigh him down, and the church came to symbolize restriction, judgment, and guilt from which he was determined to be free. His desire for the opposite sex, like his appetite for the giddy high of music, overrode any etiquette he felt was being imposed by society. A moment of erotic awakening had occurred as a toddler, when a white nurse, who was caring for him during a bout of pneumonia, playfully spanked him, which he found exciting. Later he encountered a white couple making love outdoors in the grass, and their suggestion of a ménage à trois progressed as far as Berry rubbing the woman’s feet—which was accompanied by a stern lecture from the woman about how white women were strictly off-limits; Black boys, she warned him, had been murdered for less. Music, sex, and race became powerfully connected in his mind—and decades later Berry’s taste for voyeurism landed him in serious trouble.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, at Sumner High School in St. Louis, only one teacher—Julia Davis—managed to overcome Berry’s reluctance to engage. Davis cared about her pupils’ well-being and also made sure to incorporate African American history into her teaching. She recognized that Berry wasn’t wasting time in the music room; he was learning the basics of playing saxophone, piano, and drums, an education she was eager to encourage. Davis told him that making a living as a musician was possible. Using a borrowed guitar, Berry started to imitate blues pieces he had heard on the jukebox, finding the chord patterns on the guitar through trial and error after a school friend showed him some basic finger positions.

The journey Berry made from his school days—via road trips out of St. Louis—toward improving his abilities on the guitar, then playing amateur gigs and recording “Maybellene,” was remarkably fast. (Though one of those road trips ended with his serving three years in a reformatory after robbing three shops in Kansas City at gunpoint—albeit, he claimed, with a broken weapon.) Berry approached Muddy Waters during a gig in Chicago to ask for advice about making a record. Waters was, at that time, Chess Records’ “moneymaker,” Smith says, and his suggestion to go see Leonard Chess (Phil’s brother) the next morning was the only encouragement Berry needed.

Smith excels at disentangling the details of Berry’s relationship to both songwriting and his instrument. In 2002 Berry found himself in court, not defending himself against allegations of sex crimes but as part of a financial dispute that required him to clarify his songwriting process. The lawyers who questioned him that day managed to extract more information than any music journalist ever had. He didn’t “write” songs so much as generate new material out of ones that already existed. “Maybellene” had been written over an old hillbilly tune, “Ida Red.” A song by Big Joe Turner, “Wee Baby Blues,” which his group was playing every night in the mid-1950s, gradually took on a new identity as “Wee Wee Hours.” Berry never brought a completed song to a recording session; songs reached their final form only once they were committed to record. He likened the process of collaboration with his musicians, especially his brilliant pianist Johnnie Johnson, to kicking around ideas to see where they landed—each musician’s instrumental style shaping and molding the material.

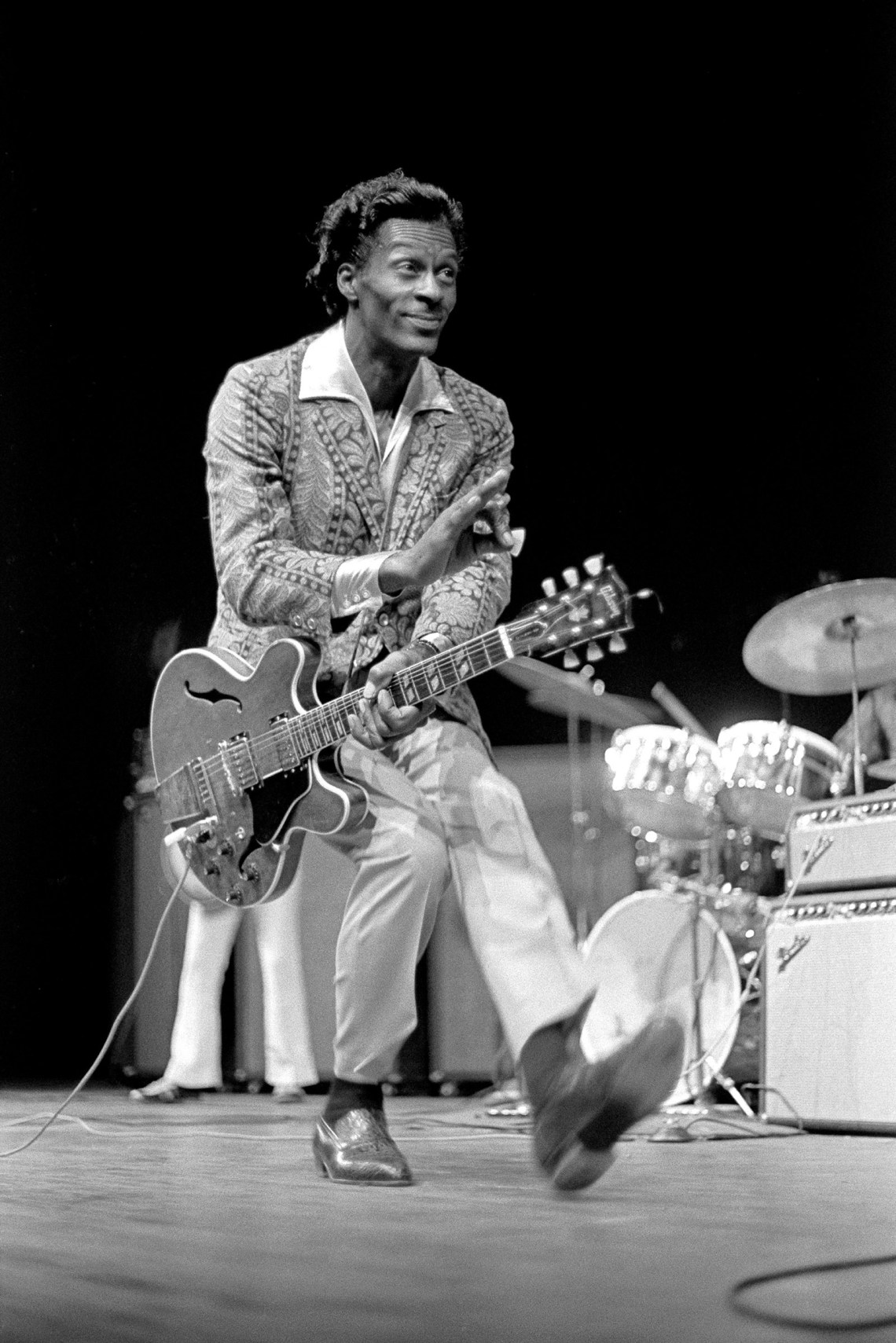

Berry learned his craft on an electric guitar, Smith notes, whereas many guitarists of earlier generations had tailored their acoustic instincts to the electric instrument—a painful process. And Berry didn’t just learn on an electric instrument; his whole aptitude for sound was actively shaped by its resonant bounce and throb. To watch him perform was to witness a musician saturate himself in sound. Carl Sally, who played saxophone with him in 1956, tells Smith about how the platform moved with the vibrations of the speakers, how his sound was powerful enough to enter your body. Berry stalked the stage during shows to locate spots where the sound of his guitar might vibrate most freely. He swirled and twisted the instrument around his body as he soloed; then there was his signature duckwalk, when he would crouch down and waddle across the stage, in rigid lockstep with the groove. “He discovered that playing the guitar had a physical component,” Smith writes. “Moving around with the instrument changed the sound, changed the feeling, and changed the mood of the room.” Smith leaves only one intriguing piece of information unexplained: Berry, who couldn’t read conventional music notation, developed a system of his own based on arithmetic, but Smith makes no attempt to describe it.

Berry’s fearlessness when it came to traversing racial boundaries while touring, mixing with white fans (including white women), sometimes left other musicians feeling vulnerable. He began constructing a mythology around himself, with the aim of putting distance between the musician he had become and his earlier years. When he joined the American Federation of Musicians in 1952 he signed up as “Charles Berryn.” (Smith speculates that he liked that it sounded like “baron.”) After he became successful, but before he was so famous that he couldn’t hide the truth, he started telling journalists that he had been born in San Jose, California. Berry generally held interviewers in contempt. He enjoyed teasing them and throwing them off the scent.

Many Berry songs, similarly, were about identity. “Roll Over Beethoven”—in the second verse, the title words are followed by the line “Tell Tchaikovsky the news”—was not so much about Beethoven’s music but about what Beethoven (and Tchaikovsky) had come to symbolize as a cultural marker to white, middle-class America. Smith describes how the song spilled out of Berry’s feelings about his idol Nat King Cole, who, having suffered the indignity of being physically attacked onstage in Alabama, could not quite bring himself to affirm publicly that he was more than an entertainer whose role was simply “putting a smile on people’s faces.”

Berry believed that life in America had moved beyond such an awkward, one-sided compromise. Although Black entertainers maintained distance from their white audiences for their own physical safety, that hadn’t helped Cole. Having Beethoven roll over was code for a cultural shift that Berry felt he was helping to start. A later song, “Back in the USA,” was written after he toured Australia, where he was disturbed to learn that Aboriginal people were denied full citizenship in their own homeland. Yes, America was a problem, but Berry believed wholeheartedly in his country, and that barriers existed to be knocked down.

The message of his music became clear with the opening of Berry Park, an idealistic amusement park and music venue in St. Louis that had various iterations during the late 1950s and 1960s. Anyone of any race could pay twenty-five cents to jump into his guitar-shaped outdoor swimming pool, making an important statement in an area with a miserable history of forbidding Blacks and whites from swimming together.

Berry’s comeback following the Janice Escalanti affair was slow and, at first, halting. His playing lost its sparkle after his confinement, which began in early 1962. He also emerged into a very different rock-and-roll landscape than the one he had known. In the interim, groups like the Kinks, the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles had appeared, covering his songs and enjoying immense commercial success in doing so, while talking up the depth of his influence in interviews.

Berry’s tendency to let his behavior undermine his achievements, musical and social, is dismaying. It’s rare to read a music biography with such a pitiful and prolonged end. His only number 1 single—the cringeworthy “My Ding-a-Ling” (1972), an update of a facile novelty record sung originally by Dave Bartholomew twenty years earlier—showed the danger of departing from the path he knew. In the lyric, Berry fiddles with bells hanging off a string (his “ding-a-ling”) until the big reveal: he is actually playing with a part of his own anatomy. It might have handed him a hit, but his musicians loathed playing the song and wondered why he was bothering with such cheap laughs.

From the 1970s until his death, Berry largely stuck to the material and blueprints that had made him a star. The desire of audiences to hear this touchstone of rock and roll’s golden era proved insatiable, and he maintained a hectic touring schedule, always working with local musicians to cut touring costs and demanding payment of exorbitant amounts in cash before he’d walk onstage. The music Berry played was labeled “legacy rock,” although live recordings capture the improvisational vitality of these late-period performances; the songs were fixed in history, but Berry’s insistently alert guitar playing couldn’t help but keep the music fresh and spontaneous.

More scandals emerged. He was invited to the White House in 1979 to perform for Jimmy Carter, despite having been charged with tax evasion a few days earlier. (He served four months after declining to pay the fine and back taxes.) His violence against women and sexual misconduct escalated alarmingly. In 1988 he was sued for $5 million by a woman—not named by Smith but reported to be the singer Marilyn O’Brien Boteler—who accused him of punching her in the mouth during an argument in a New York hotel the year before; Berry failed to appear in court and later agreed to pay her a much-reduced amount.

In 1990 he faced public ridicule when High Society magazine acquired nude photos of him in the company of various women, published under the tease “The Only Magazine with the Balls to Show Chuck’s Berries!” Pornographic material, some of which involved underage girls, was uncovered during a subsequent raid on his home, after police received a tip, unproven in the end, that he was carrying large quantities of cocaine. Charges surrounding the underage material were eventually dropped, but the investigations led to other appalling revelations. Videos, which Smith suggests were stolen from Berry’s house, emerged showing him urinating on prostitutes, and the discovery of hidden camera footage led nearly two hundred women to sue him for filming them in the bathroom of a restaurant he owned in Wentzville.

A photograph taken at Berry’s memorial service in April 2017—only months before the abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein became public—shows a group of protesters clutching signs that read, “Your idol is someone else’s abuser” and “Chuck Berry assaults 60 women y’all silent.” This is treacherous terrain for any biographer. Smith responds to the inevitable question—why give Berry’s music our respect when he behaved with such cruel and casual disregard?—by invoking William Burroughs (“a gun fanatic who shot his second wife”) and T.S. Eliot (“a profound anti-Semite”) as examples of two other artists from St. Louis whose work enriched lives even if we might find aspects of their personal conduct distasteful.

We know already that people are enormously complex and contradictory, and that those who create beautiful things can also lead chaotic and destructive lives. Smith mourns that Berry turned his legacy into “something so complicated,” but in reality his behavior makes it difficult to elevate him to the status of a great musician. Yet Berry’s music is something to be celebrated—and let us not forget the courage and persistence with which he swatted away racial hatred. In a 2008 interview Berry declared, “I don’t get so much [racism] now, because of the fame,” although a couple years earlier he had complained that he was “denied his equal civil rights because of the US’s racially motivated criminal prosecution.” Smith suggests that, although Berry did “bad things to people who trusted him,” ultimately he was “victimized by racist forces” who “didn’t like his kind” and treated him more severely than if he’d been white. The great strength of Smith’s book lies in the detail of its evidence, which lays out his subject’s profound musical achievements and personal failings—and invites readers to reach their own conclusions.