The Blaise Cendrars show at the Morgan may have been contained in a space about the size of a studio apartment, but it seemed much larger, because like its subject it pointed in so many different directions at once. Cendrars was a poet who was also involved, in various capacities, with painting, music, film, photography, and even advertising. As the curator, Sheelagh Bevan, wrote in a wall text, he “never aligned himself with a single school of art, though his career was intertwined with figures tied to Cubism, Orphism, Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism.” Cendrars was a lightning rod for all the artistic currents that blew through Paris between about 1912 and the mid-1920s. His experiences and travels made him seem larger than life in his own time, a kind of poetic Jack London, and he kept reinventing himself as the decades passed, dropping poetry for novels and then journalism, and then a series of what today might be called autofictions: memoirs laced with more than the usual amount of malarkey.

He was born Frédéric Sauser in 1887, in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, the center of the watchmaking industry. Switzerland tends to export its artists anyway, but the young Sauser became cosmopolitan early on. His father, an entrepreneur always just one sure idea away from success, moved the family to Naples with the notion of importing German beer to Italy; there may have been an earlier family sojourn in Alexandria as well.

Back in Switzerland after the inevitable bankruptcy a few years later, the teenager couldn’t adapt, cutting school regularly, so his father indentured him to a Russian watch dealer in St. Petersburg. He arrived at the height of the Russo-Japanese War, witnessed the effects of the failed revolution of 1905, and traveled to Moscow, to the great fair at Nizhniy Novgorod, and at least once on the Trans-Siberian Railway. In St. Petersburg he spent all his free time at the library. He later claimed he had written his first book there, The Legend of Novgorod, and had it translated into Russian in 1909 and issued in an edition of fourteen by a friendly librarian; no verifiable copy has ever turned up.

In any case, he was mainly reading French books. Around 1911 he decided to relocate to Paris and become a poet. There he found his way to a complex of hovel-studios in Montparnasse called La Ruche (the Hive), where he met Marc Chagall and Amedeo Modigliani, among others, but he couldn’t get a footing. (He would be chronically impoverished throughout his career.) After floundering in various European cities, in late 1911 he followed Félicie Poznanska, born in the Łódź ghetto, to New York, where she taught in the anarchist Ferrer School. For a while they lived on West 96th Street in a wooden house, and he made ends meet by playing piano in a Bowery nickelodeon.

There was nothing much happening in New York then, artistically speaking—even Alfred Stieglitz’s Little Galleries were all about bringing the news from Europe. But something about being in the city caused Sauser to change his name to Blaise Cendrars, allegedly from a line of Nietzsche: “And everything of mine turns to mere cinders/What I love and what I do.”

It also resulted in his first long poem, Les Paques à New York (Easter in New York), which he published at his own expense after returning to Paris in 1912—a reckoning with the Christian deity in rhymed but unmetered couplets that have the rough music of popular broadsides. (The 1926 edition was illustrated by the Belgian narrative woodcut artist Frans Masereel; poems and prints match perfectly in their high-contrast Expressionist drama.) In 1913 Guillaume Apollinaire, Cendrars’s main rival for the crown of modernity among Paris poets, published “Zone,” which is almost an answer song to Cendrars’s in both form and content, but it takes the conceit further, into a kaleidoscopic cinema of present and recollected images. Apollinaire can be said to have won that hand.

Like Apollinaire—“a poet among the painters”—Cendrars was thoroughly at home among visual artists. He wrote about Fernand Léger, Chagall, and Alexander Archipenko; Léger, Moïse Kisling, and Modigliani illustrated his books. He was especially close to Robert and Sonia Delaunay, with whom he shared a wholehearted love of Paris the modern and its heraldic beast, the Eiffel Tower.

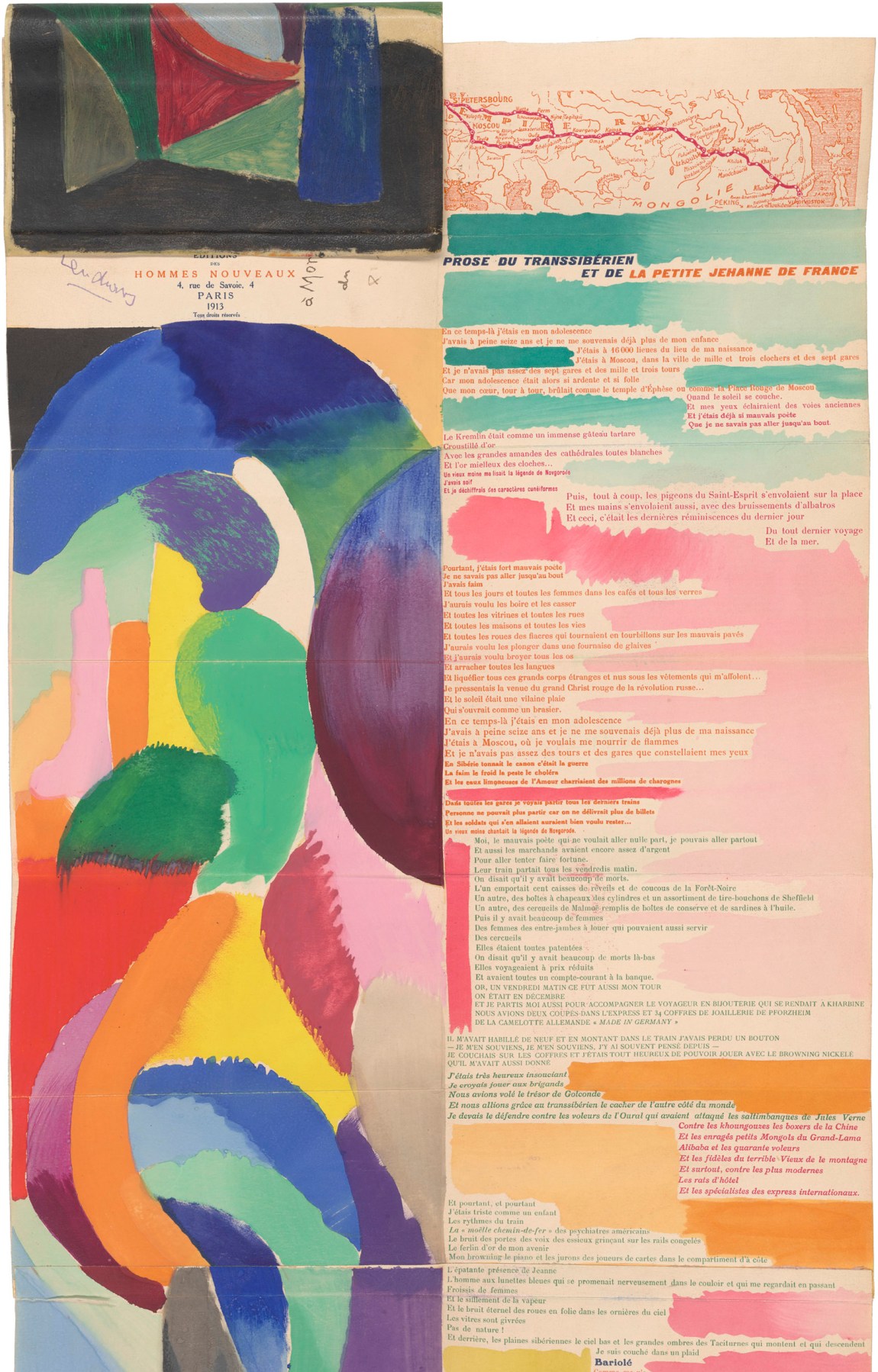

In 1913 Cendrars and Sonia (who was born in Odesa) collaborated on the spectacular Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France (Prose of the Trans-Siberian and of Little Jeanne of France)—an example of which, towering over the room at the Morgan, was the centerpiece of the show.

Advertisement

Cendrars’s long poem is printed as an accordion book on a sheet of paper nearly seven feet high, in a series of different colors and typefaces, with Delaunay’s painting, electric and undimmed by time, running down the left alongside the text. The planned print run of 150 would, if stacked vertically end to end, have reached the top of the Eiffel Tower. (Only about sixty were printed.) The poem tumbles along, as if bouncing on rails, recounting a journey from Moscow to Harbin with digressions and asides and cooing to his companion, little Jeanne, who may be a French sex worker adrift in the East, and who keeps asking Blaise if they’re really a long way from Montmartre:

Back then I was still quite young

I was barely sixteen but I’d already forgotten about where I was born

I was in Moscow wanting to wolf down flames

And there weren’t enough of those towers and stations sparkling in my eyes

In Siberia the artillery rumbled—it was war

Hunger cold plague cholera

And the muddy waters of the Amur carrying along millions of corpses

In every station I watched the last trains leave

That’s all: they weren’t selling any more tickets

And the soldiers would far rather have stayed…

An old monk was singing the legend of Novgorod.(translated by Ron Padgett)

Its sawtooth lines and cascading rhythms mark it not only as one of the signal poems of pre-war French modernism but also as a pioneering work of beatnik poetry. A progenitor of spontaneous bop prosody, Cendrars made a direct impact on proto-beats in Paris after World War II—Jean-Paul Clébert, Jacques Yonnet, Robert Giraud—and eventually on Ginsberg and Kerouac and the first and second iterations of the New York School; Ron Padgett published his definitive translation of Cendrars’s Complete Poems in 1992.

Cendrars always claimed that Prose du Transsibérien recounted his experiences with the Russian watch merchant, but there is no evidence he went very far on the train, certainly not to Harbin. However, recent scholarship has turned up evidence of the Trans-Siberian Express at the Paris Exposition of 1900, a restaurant Cendrars visited, with his parents, where dining in stationary railcars was accompanied by a panorama continuously rolling along outside the windows.

When war broke out in 1914 Cendrars rallied to the cause, calling on other expats to join him in the Foreign Legion. He lost his right arm—his writing arm—at the Navarin farm offensive in the Second Battle of Champagne in 1915, and thereafter wore his empty sleeve proudly. He taught himself to write with his left hand and was soon on again, publishing his account of his wartime experiences, J’ai tué (I Have Killed), in 1918 with illustrations by Léger; it was the first work of his published in translation in the US, by The Plowshare in Woodstock, New York, in 1919. Also in 1918 he published Le Panama, Ou les Aventures de Mes Sept Oncles (Panama, or The Adventures of My Seven Uncles) in another extraordinary format, its quarto pages intended to be folded in half again, so that it looks a lot like a Union Pacific timetable, rigorously imitating the railroad’s brilliant red, white, and blue design. Within, the poem’s sections are marked off by twenty-five maps of principal American rail routes, plus a boosterish advertisement for the coming city of Denver, Colorado.

Le Panama, very much in the spirit of the Transsibérien, is a galloping meditation and an effusion of place-names, studded with initial capitals like so many cubic zirconia, harnessing their suggestive power at a time when more than half the globe was terra incognita for most people anywhere:

The Milky Way around my neck

The two hemispheres on my eyes

At top speed

There are no more breakdowns

If I had time to save a little money I’d fly in the airplane races

I’ve reserved a seat on the first train through the tunnel beneath the English Channel

I’m the first flyer to cross the Atlantic in a monocoque

900 million(translated by Ron Padgett)

It was translated into English in 1931 by John Dos Passos, who borrowed from Cendrars the montage style he employed in his U.S.A. trilogy.

Cendrars in turn borrowed from the painters, having observed Picasso and Georges Braque in the act of inventing Cubism, and along with it their painterly use of collage. No slouch at analogic thinking, Cendrars adapted the concept to literature in a variety of ways. The poems in Kodak (1924; retitled Documentaires after a cease-and-desist from the Eastman Corporation), which sound remarkably like Cendrars’s voice, are mostly lifted from The Mysterious Doctor Cornelius, one of the voluminous pulp novels by Cendrars’s friend Gustave Le Rouge. Cendrars was trying to prove the richness of Le Rouge’s prose to its self-doubting author, who wrote compulsively and was often cheated by flim-flam publishers.

Advertisement

Cendrars, by all accounts a boon companion, maintained friendships among every sort of grouplet in Paris, not only the painters but also American writers (Dos Passos, Hemingway, Henry Miller); composers (Les Six—Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, and Germaine Taillefer—three of whom set his poems to music); graphic artists (the lapidary, ubiquitous A.M. Cassandre, whom Cendrars called a “film director” of the urban streetscape and who was responsible for the Dubonnet and Nicolas posters that defined the look of Paris streets in the 1920s and 1930s and that can be seen in photographs by André Kertesz and others); photographers (especially Brassaï and the young Robert Doisneau, with whom he would collaborate on the great La Banlieue de Paris in 1949); and filmmakers, in particular the visionary Abel Gance, with whom he worked on J’accuse (1919) and then La Roue (1923).

A selection of electrifying sequences from the latter played on a loop at the Morgan: an intense rapid montage of trains and rails and switches, traumatic memories of a climbing accident, hallucinations that look like Rayographs. Cendrars’s 1925 novel L’Or, based on the exploits of a fellow Swiss adventurer, was later adapted by Hollywood as Sutter’s Gold (directed by James Cruze, 1936) and simultaneously by the Nazi cinema in Munich as the unauthorized Emperor of California (directed by Luis Trenker, also 1936).

Despite the many lures of Paris, Cendrars couldn’t stop traveling. He went to Brazil three times in the 1920s, the trips paid for by a collector he met through the Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral, who supplied the illustrations for the resulting book of poems, Feuilles de route (Travel Notes, 1924). In “The Mumus,” one of the book’s many short poems (they really are travel notes), he describes a village near Dakar where his ship put in before crossing the Atlantic:

Oh these black women you meet around the black village at the shops where percale is measured out for trade

No other women in the world possess that distinctiveness that nobility that bearing that demeanor that carriage that elegance that nonchalance that refinement that neatness that hygiene that health that optimism that obliviousness that youthfulness that taste

(translated by Ron Padgett)

Cendrars fell deeply in love with Brazil. As Bevan notes in a wall text:

Cendrars indiscriminately applied his theories of art to indigenous languages and non-White peoples. In writings, he seemed to view Brazil’s industrial ambitions and the varied economic conditions of its multiracial citizens as the ultimate embodiment of contrast—a manifestation of modern life Cendrars had been seeking in art and language.

He saw Brazil as a nationwide example of montage, which in the 1920s was at the peak of its revolutionary promise. Montage—as defined around that time by Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin, among others—was the artistic manifestation of the dialectic, the acceptance of contradiction by means of radical but balanced contrast. It was the art of the new age, which artists were magically bringing into being before anyone had time to put up barricades. To extend that premise to an entire multiracial society was to imagine life and art merging seamlessly on the terrain of the daily, as if the revolution had already succeeded.

The exhibition’s chronology ends there, as Cendrars’s work becomes much less visual thereafter. The scene had changed; people were no longer young and kept more to themselves. He wrote a series of adventurous novels, which are like prose elaborations of his poems in their range and kinetics. The best is probably the horrifically titled Moravagine (1926), about a post-gothic monster along the lines of Lautréamont’s Maldoror, a complex exorcism of the evil Cendrars saw within himself.

In the 1930s, in France the age of the grands reportages, Cendrars investigated crime and Hollywood; he embedded himself with the British army in 1940. In 1943, isolated in Provence during the depths of World War II, he began the first of the four books published here as The Astonished Man (1945, translated 1970), Lice (1946, translated 1973), Planus (1948, translated 1972), and Sky (1949, translated 1992) (not all of them are currently in print), which form a kind of rambling memoir in four distinct parts—the first is about his youthful travels, the second about the war and losing his arm, and so on—all of it set to music, as it were, by the distinctive voice that runs through the whole of his work, rolling and tumbling unstoppably, ascending into rhapsodic flight or descending into monosyllables and ellipses, recording ambient detail or veering off into digressions of all sizes, confiding and joshing and evoking and prophesizing. Their premise is autobiographical, but they provide notoriously unreliable testimony and are the richer for it. (If you truly want the facts, his daughter Miriam Cendrars’s eight-hundred-page biography is the place to go.)

Cendrars’s work is shot through with youth and impulsiveness and uncorrupted enthusiasm and a hunger for experience, qualities he managed to preserve into old age, through two wars and assorted miseries, as he slowly became the face that first stared out at me from the cover of the Selected Writings published by New Directions in 1962, who didn’t look like a poet but looked like my uncle, a Dutch topiary gardener who was economically also my godfather: same squint, same drinker’s nose, same ironic grimace of a smile, same cigarette butt with inch-long ash permanently glued to lower lip, the face of authenticity and hijinks.