This book will be denounced in Beijing. Ha Jin’s The Woman Back from Moscow is a novel based on the life of Sun Weishi, an adopted daughter of Chinese premier Zhou Enlai, whose brilliant mind and intensive study in Moscow of the Stanislavski acting method brought her to the pinnacle of China’s theatrical world during the Mao years. Her beauty and effervescent personality attracted powerful men—not only Zhou, who doted on her, but also Lin Biao, the Chinese Communist Party’s leading general, who divorced his wife in order to propose marriage to her (unsuccessfully), and Mao, who apparently raped her during a long rail trip. She had several other suitors and eventually married the film star Jin Shan.

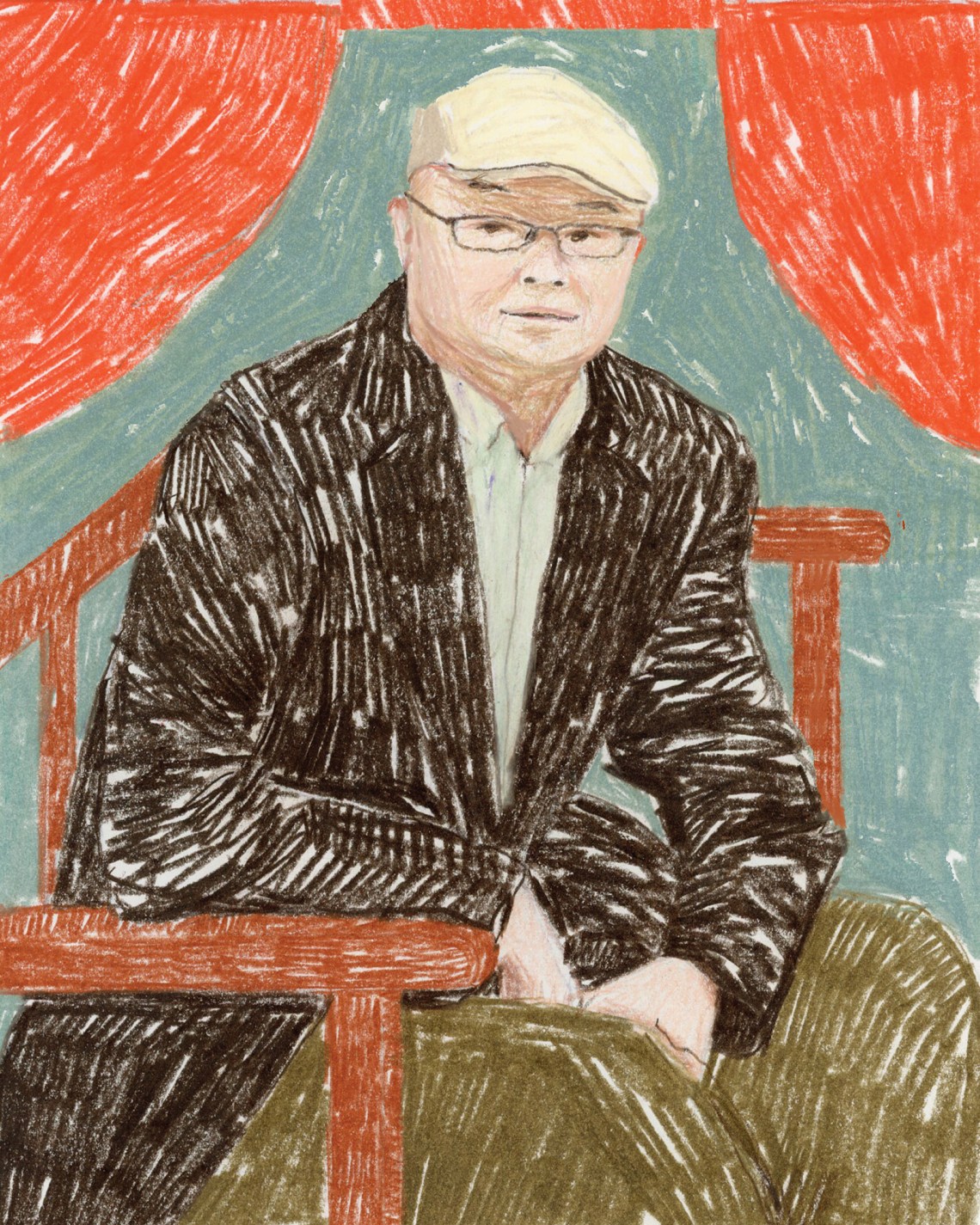

Ha Jin, a former soldier in the Chinese army who came to the US in 1985 at age twenty-nine to do graduate study, has written ten novels in English as well as poetry, short stories, and essays. In The Woman Back from Moscow, he conveys in supple prose what Beijing inevitably will regard as too much truth about the history of the CCP. Perhaps anticipating trouble, Other Press offers a publisher’s note at the book’s beginning:

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

In an author’s note at the book’s end, Ha Jin lists five works of nonfiction that were his main sources. Although he imagines dialogue and invents some connective tissue, he writes, “Most of the events and details in this novel were factual…. Reality is often more fantastic than fiction, so I did my best to remain faithful to Sun Weishi’s life story.” He calls her Sun Yomei, a name she used in personal correspondence, because the name Weishi “is hard to pronounce in English and might upset the cadence of sentences.”

Scandal is popular everywhere, of course, but in Communist China historical truth-telling carries special weight, because it questions the legitimacy of the regime. Although the CCP’s “red families” (offspring of the original Mao-era revolutionaries) heavily influence elite politics, they do not enjoy a formal right to rule of the kind that, in imperial times, was passed from father to son. Nor does legitimacy derive from elections, because the CCP does not allow them. Legitimacy depends crucially on the historical record of how the rulers have performed. Some observers, including Cui Weiping, a prominent Chinese public intellectual, have argued that history has taken on an almost religious significance in Chinese politics. Religions project ideals into the future and offer followers the hope of reaching them. China’s history-religion projects ideals onto the past and cites them as the reasons why a regime should continue. But a serious problem arises for this history-religion. The future has not yet happened, so religious promises cannot be falsified. The past has happened, so it can be.

It thus becomes a matter of utmost importance that the appearance of political virtue be preserved in accounts of events such as the Communists’ Long March to Yan’an in the mid-1930s, their establishment there of an idyllic community, their founding of a “people’s” republic in 1949, and much more. Of course there must be no mention of mass political executions or a huge famine. A whitewashed version of history becomes a kind of religious idol. It is placed beyond the public’s questioning and can be tweaked only when a leader needs support for a current policy.

Guarding official history becomes the métier of a group of state-sponsored “historians” who construct versions of the past and are not bothered by any discrepancies between their accounts and what actually happened. “It does not even enter their thinking,” says Cui Weiping. They and their superiors measure the quality of their work not by its degree of truth but by its likely effectiveness in selling the history-religion. This is why Beijing’s red royalty will see Ha Jin’s book rather as a convention of manicured cats might see an approaching bulldog. What he writes is fiction, but it is far closer to truth-telling than what the regime calls history.

Talk in China about elite politics has long made use of stage metaphors that originally come from popular opera. A leader gaining power “ascends the stage,” in losing it “leaves the stage,” and while on it plays roles. Actual life is covered up. “Mao” is a fabricated Mao, “Lin Biao” a fabricated Lin Biao. Ha Jin’s novel removes the masks. He presents human beings enmeshed in thoughts and emotions that other human beings will recognize.

The culture we glimpse in the novel is the special culture of the Communist superelite, which differs greatly from the way most ordinary Chinese live. For example, socialist ideology notwithstanding, members of the elite keep servants. From the dusty caves of Yan’an in the late 1930s to the red-hot “class struggle” of the late 1960s in Beijing, there are always maids to peel pears, orderlies to deliver lunch boxes, and guards to watch doorways, and when a child arrives the family goes out and hires a nanny. Ha Jin does not spotlight this aspect of life. I am doing that, plucking details from a narration within which they are unobtrusive, which adds to their credibility. We learn that Mao’s wife Jiang Qing enjoys a villa, a yacht, and a “flock of servants” in Hangzhou only because these facts happen to appear as Ha Jin is relating a story about her resentment of a rival.

Advertisement

The sufferings of the elite are of a special kind, different from the sufferings of “the masses.” Sun Yomei and her colleagues know about the attack in 1951 on the film The Life of Wu Xun, which Mao, in an apparent effort to control the film industry, instructs his underlings to denounce as a “model of reconciliation with feudalistic and reactionary forces.” His words are, to be sure, a harsh blow. But during the same years (1949–1953) putative “landlords” were being executed by the millions in a land reform campaign. Yomei and her artist colleagues make no mention of that. They likely are unaware of it. They also do not remark upon the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957, in which hundreds of thousands of intellectuals were killed, jailed, or persecuted, or the Mao-induced famine of 1959–1961 that took at least 30 million lives, except when such events tangentially affect a person in their lives. They are ethical people; we trust that they would be concerned by such matters if they were aware of them.

They live in a cocoon, but the culture inside is hardly protective. It is tense and bereft of trust. Familial affection is present, but it gives way to politics whenever necessary. President Liu Shaoqi is willing to derail the marriages of two of his children, who have non-Chinese partners, because of “revolutionary needs.” Zhou Enlai clearly cares for his adopted daughter. He coaches her in how to survive: “Just be careful about what you say in your letters. Always assume that some other eyes will read your letters before they reach me.” But during the Cultural Revolution, when Zhou is faced with the dilemma of whether to sacrifice Yomei in order to protect himself from Jiang Qing, he signs a warrant for her detention that leads to her torture and death in prison. An aunt of Yomei’s, observing Zhou’s maintenance of a suave exterior, calls him a “smiling snake.”

Zhou is no anomaly. He lives in an environment where, in the end, people can trust only themselves. The distinguished Australian Sinologist Simon Leys once observed that comparisons of the CCP elite to the mafia are in a sense unfair to the mafia, in which a certain loyalty to “brothers” does play a part. Losers of political battles at the top of the CCP generally are not relegated to comfortable retirements—they go to prison or worse. Zhou did not wish to seal Yomei’s fate; he was forced to when it became clear that it was either him or her.

Political power so infuses personal relations that the question “How might I use this person?” is almost always in the background. As Mao awakes in his railroad car, lying next to Yomei, whom he has raped during the night, he lights a cigarette, blows “two tusks of smoke out of the edges of his mouth,” and says, “I could tell you were not a virgin…. Please join my staff. I need your help and will be considerate to you.” Shocked and in tears, Yomei bolts from the car, but not before Mao adds, “Even though you don’t want to work for me, keep in mind that I’ll be happy to help you when you need me.”

Many years later, she does need him. Red Guards are torturing her brother Sun Yang, who has written a laudatory biography of Zhu Deh, Mao’s rival in the claim to be the founder of the People’s Liberation Army. Yomei appeals in person to Mao to intervene for her brother. He listens and says that “we should look into” the matter. In fact he does no investigating, but neither he nor Yomei finds it extraordinary that a rape victim is asking her rapist for a favor.

This is within the culture. The “scar literature” that followed Mao’s death in the late 1970s offers many credible accounts of how victims had to defer to the very people who had once harmed them. This problem was not just in elite culture; it reached as deep into society as Party rule did. The writer Zheng Yi records the case of a woman whose preschool son was killed because his father had been a “class enemy.” Three men tied the boy by a rope to the tailgate of a truck and dragged him until he was dead. Fifteen years later the three murderers visited the mother’s home, accompanied by a Party official, to perform a ritual “apology.” She was obliged to pour tea for them.*

Advertisement

During Yomei’s final days—she died in prison in 1968—police grill her on her personal connections. It is their job to gather intelligence that can be useful in future political combat. Yomei is annoyed at one point with their persistent questions about sex. They wonder whether Zhou’s affection for his adopted daughter was in part sexual. To find evidence of this would neither raise nor lower Yomei’s political standing but would be immensely useful to Jiang Qing in her bitter rivalry with Zhou. Yomei asks her tormentors, “Why are you so interested in what happened inside the top leaders’ pants?”

For reasons that are unclear to me, under China’s Communist regime sexual misbehavior came to be considered a strong indicator of depravity. In imperial times, a man’s wealth could be measured by how many women (both wives and concubines) he accumulated and how many children they produced. Sexual prowess was admired. Dalliance outside the home was not exactly favored, but it was seen more as a profligate use of time—like chatting in teahouses or listening to singsong—than a moral transgression. In the Communist years, however, extramarital sex came to be seen as an unambiguous sign of foul character and was often used as a weapon in political struggle.

In 2016 Xu Zhang-run, a distinguished professor of law at Tsinghua University, began publishing essays that criticized Xi Jinping’s national policies in fundamental ways. Xu’s essays were erudite, broadly conceived, and written in an elegant semiclassical Chinese. Xi needed to fight back, but how? He was no literary match for Xu, so his weapons were limited to firing the professor from his post, depriving him of his pension, blacklisting him, and detaining him. And what else? Charging him with visiting prostitutes in Sichuan. The accusation was sufficiently aggressive that its falsity did not seem to matter.

Accusations of sexual excess could be potent weapons against the powerful as well as their victims. In the mid-1990s, after Mao’s personal physician Li Zhisui published his book The Private Life of Chairman Mao, Chinese people focused quickly on its revelations of Mao’s lifelong appetite for young women. Slower and more sober readings of the lengthy book showed in detail how Mao treated people heartlessly and caused the unspeakable suffering of millions. But what grabbed public attention was his rampant lust.

Was there no sign of Maoist ideals in Yomei’s milieu—of serving the people or building a new socialist China? In Ha Jin’s telling, such ideas rarely enter the thinking of top leaders. Jiang Qing wants to create a “new” Chinese opera, but her goals are personal fame and power, not benefit to society. Mao never mentions to Yomei any rationales for collectivizing agriculture, which his regime was pursuing in the 1950s, but when she shows him a Soviet film of an atomic bomb explosion he is smitten by the “typhoon of fire” and becomes obsessed with getting a bomb for himself.

And yet there were people who did embrace the new ideals and did devote their lives to them. The main theme of Ha Jin’s book is what happened to these people, and Yomei is his main example. Sent to Moscow in 1939 with Zhou Enlai, who needs medical treatment there, Yomei stays, learns Russian, studies theater, and becomes deeply enamored of Stanislavskian principles: actors must internalize the characters they play—their thoughts, feelings, and fears, both onstage and off—and must focus intently on the drama they are participating in whether or not they have speaking roles. She finds that the best way to pursue this approach is through directing, not acting, and after she returns to China in 1950 has great success as a director and eventually begins to write her own plays.

But she soon encounters a problem that only grows larger as her work continues. She directs Pavel Korchagin, a stage adaptation of Nikolai Ostrovsky’s classic 1936 Soviet novel How the Steel Was Tempered. The art flows from within her, the critical reception is enthusiastic, and the success leaves her euphoric. Then she hears Mao’s encomium, in which he states she has “won honor for China and for our Party.” This shocks and disappoints her. She had not felt a political motivation in staging the play and finds Mao’s assertion of state sovereignty over her work inappropriate and awkward.

Years later she arrives at the view that “any extraordinary talent that emerged in arts would get noticed by the powers that be and would be harnessed to serve a cause or a political purpose.” In such circumstances, pursuit of creativity is futile. Worse, it could be dangerous. Innovation could cause a person to stand out from a group, whereas “in this country, it was always safer to remain common and average.”

I was reminded of an exchange I had with the Chinese writer Cao Guanlong in June 1980. Cao worked in a bicycle factory in Shanghai. When he asked me if American bikes were different from Chinese ones, I commented that most of ours had gears. I felt apprehensive that my words might embarrass him on behalf of his country and was surprised to hear his quick response:

We know how to install gears. I can do it. My friends can, too. But we don’t dare. Anyone who added gears would be stepping out of line, upsetting the uniformity. The leaders don’t like that. So we don’t do it. Not worth it.

During the Cultural Revolution Yomei moves to an oil field in remote Heilongjiang Province, where she lives among ordinary workers and learns of their lives and ordeals, especially those of the women. She writes a play called The Rising Sun that becomes a major success in Beijing and other cities. It is an excellent example of what Mao, ever since his famous Yan’an talks in 1942, has been demanding that Chinese writers do: go among the workers, farmers, and soldiers, “directly experience” their lives, and bring their struggles and triumphs into art. In the end, though, the political authorities reject Yomei’s work as “bourgeois and reactionary.” At the cost of her life she learns that what Mao has actually wanted from artists all along is not the autonomous pursuit of ideals but political fealty. An artist’s job is to support the Party. Her or his work is to be poured into Party molds and presented as Party products.

In an art class at a primary school in May 1973, during my first trip to China, I saw a young boy drawing a picture of an airplane crashing in flames. The student sitting next to him was drawing the same thing. Then I saw that all the students in the class—thirty or so—were drawing the same scene in the same way. The teacher had provided a model. The drawing showed the fate of Lin Biao, who in September 1971, it was said, had attempted a coup against Mao and fled to the Soviet Union, but died when his plane crashed on the way. The youngsters’ drawings were an example of how artistic effort from below fills molds prescribed from above. This was the system that stifled Yomei and ultimately destroyed her.

Yomei’s experience in the theater exemplifies a broad pattern in the fate of “new socialist art” in the 1950s. Writers and artists of many kinds supported the new regime and were eager to promote its ideals. If this meant changing their work, that was all right—it was a welcome challenge. China’s most popular performing art at the time was the comedic dialogue form known as xiangsheng. Long disparaged as low-class, xiangsheng performers were keen for the laurel of “socialist worker” and ready to work to deserve it. The regime’s instructions to them were to transform their intrinsically satiric art into one that praised the new society. But that was a puzzle: How could satire be used to praise? One could satirize class enemies, but that approach quickly grew dreary. One could satirize men who believed that “the new woman” could not drive trucks, but problems arose when audiences didn’t get the joke or laughed at the wrong things.

Despite the challenges, by 1956 a number of xiangsheng experiments had succeeded, and it appeared that a new socialist art indeed was at hand. But as with Yomei and the theater, the regime was not seeking autonomous efforts at anything. It wanted control. Independence of any kind was a threat. In 1957 He Chi, the most brilliant xiangsheng innovator to that point, was labeled a “rightist” and sent to a labor camp for twenty-two years. Others in the xiangsheng world noticed, and the experiments ended.

These examples from art illustrate a condition of life in Communist Chinese society that, although it is omnipresent and substantial, foreigners seldom notice. From the beginnings of the Communist regime until the present, there have always been popular thoughts, feelings, and initiatives that have been distinct from political labels and prescriptions. A concept like “ordinary life values” deserves a much larger scope in analyses of China than it normally gets. In the 1950s, when factories, schools, hospitals, and other institutions were converted into Party-led “work units,” people did not ask, “How can I contribute most to the collective?” but “How can I get the most for my family from the new system?” Today a farmer getting out of bed in the plains of Gansu Province will be thinking not about “the thoughts of Xi Jinping in the new era” but about things like the day’s weather and food, clothing, medicine, and shelter for his or her family. If a political thought does occur to the farmer, it will likely be about a local bully, not about the “cult” of Falun Gong or the traitorous Dalai Lama.

This distinction between unofficial and official life holds from the bottom of society to the top. The actual life of the red elite that Ha Jin depicts could hardly differ more from its officially projected images of giving speeches, doing inspection tours, and in other ways focusing on “service to the people.” The questions “What best fits the system?” and “What best serves my interests?” are asked in parallel by people at all levels, and they seldom have the same answers. In his memoirs the dissident physicist Fang Lizhi recalls how Teng Teng, vice-chair of China’s State Education Commission in July 1989, summoned American ambassador James Lilley to berate him about how the US was allowing Chinese students who had spoken out against the Tiananmen massacre to remain in the US indefinitely. An hour after returning to the embassy, Lilley got a telephone call from Teng Teng’s secretary asking him to give special attention to Teng’s wife and children, who were seeking that same “indefinite residence” status in the US. There are plenty of other examples like this. The “split consciousness” of Chinese people in recent times has been widely noted.

Increasing repression under Xi, who came to power in 2012, has made it difficult for Chinese writers to present unapproved history. A few try, though, and with admirable success. Ian Johnson’s Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future (2023) shows how a dozen or so writers and filmmakers, in loose association and using rudimentary tools, have been uncovering evidence of labor camps, famines, massacres, and other inglorious historical events that the government claims to be nonexistent. Johnson’s “underground historians” work as if with hand chisels in salt mines, digging out, with great effort and at great risk, empirical results that have unchallengeable solidity.

Ha Jin is a comrade in their mission but uses different tools and reaps a different kind of harvest. Replacing the hand chisel with a deft pen fueled by reading, imagination, and empathy, he reveals mental life. He and Johnson write of history that lies “beyond the seam,” as it were, and for Westerners this offers rare value. Most books by Western experts on China, including a few recent ones, are written as if there were no unofficial China to speak of.

People living inside China already know about the border between official and ordinary life, but they still could gain much from reading both these books. We should hope that good translations will appear. Ha Jin’s accounts of actual life at the top would come as revelations to many, especially the young. A centuries-old Chinese literary genre called yanyi—“historical fiction”—survived into the Mao years in oral storytelling and underground “hand-copied volumes.” These works recounted adventures, both true and imagined, of Mao, Zhou, Lin Biao, and other top Communists. Skulduggery abounds and the halos are gone, but the characters themselves are flat. There is no view into their inner lives—as there richly is in Ha Jin’s novel. A reader in China today might find his accounts explosive. Oddly, we might say that the most extraordinary achievement of the novel is its brilliantly credible evocation of the ordinary.

Of course the regime will ban any translation. But still it would reach many people. Today perhaps 80 million or more Internet users in China use virtual private networks to jump the government’s firewall—and that doesn’t count tens of millions of overseas Chinese.

This Issue

December 7, 2023

No Endgame in Gaza

Invasion, Day by Day

Gut Instincts

-

*

See Liu Binyan, “An Unnatural Disaster,” The New York Review, April 8, 1993. ↩