This essay is adapted from a talk presented as the Robert B. Silvers Lecture at the New York Public Library earlier this year.

I chose this title because I have been driven these days to speaking in more direct terms than I am accustomed to. And I think you may understand and share the sense of urgency I feel about this moment in our country. We don’t have the luxury of niceties and illusions. We are being driven to face hard truths about our republic, about our political system, about our neighbors, our safety, our understanding of who we are, about our past and our future. We are, as a country, in a moment of existential crisis, a battle for our identity. As I have said often over the past two years, there is no guarantee that we will make it out of this crisis as a democracy.

I am writing a book called Is This America? The title is what the great voting rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer asked when she appeared before the Credentials Committee at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Mrs. Hamer had been a sharecropper her entire life. When she tried to register to vote, the owner of the plantation where she and her husband worked threw them out. Later the local police beat her and other women returning from a voting rights meeting, leaving her permanently disabled.

She detailed that beating in her testimony. But her central demand was that the committee seat the organization she represented, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which grassroots activists, Black and white, had formed earlier that year in protest against the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party. The delegates of the MFDP argued that they should be considered the state’s legitimate representatives, since their party had followed all the rules and did not violate the Constitution by prohibiting Black people from serving as delegates.

Mrs. Hamer’s testimony was riveting. A simple Black woman in a cotton dress, she spoke a truth about this country that could not be denied:

Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?

This former sharecropper from Ruleville, Mississippi, knew something about America that all of those people on the Credentials Committee either did not know or purported not to know. Her question was a challenge and a demand that they see America through her eyes.

Today we are confronted by that same challenge. My experience over three decades representing those who live at the margins of our society has taught me that the people who know the most about our democracy are the ones who encounter it in its weakest places, where it fails. There are moments when we see America through their eyes—when we cannot look away. For nine minutes we all saw what seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier saw through the lens of her iPhone on a street in Minneapolis when we watched the excruciating video of the torture and murder of George Floyd. And what we saw put tens of millions of Americans in touch with a powerful truth, challenging the view of our country around the world and compelling us to confront the fundamental weaknesses of our democracy.

Seeing what happened to Floyd and the cruel inhumanity of the police officer who killed him—the certainty of impunity on Derek Chauvin’s face—made all those people certain, if only briefly, that American policing had to change. For many of us it created a sense that the changes for which we have been working needed to happen fast.

I feel a particular sense of urgency because I am not just interested in how we endure or survive this moment. Nor am I interested in a return to the former days—the days when we had a Black president, or the 1990s, or whatever period people have decided was this country’s Shangri-la. Those periods were only marginally better than the current moment, certainly in public discourse and tone. But the deeply embedded structural infirmities were the same. I have been a civil rights lawyer for thirty years and I have never been out of work. Mass incarceration, racism, wealth inequality, educational inequity, segregation, police brutality and misconduct, media bias: all these ills have long been with us.

But to say this is not to deny that something monumental has happened to our country over the past ten years. Indeed, a fundamental shift has taken place. Even as I speak, tens of millions of Americans are fully prepared to elect again as president a man of such degraded moral character, a man so void of a spirit of public service, a man so fundamentally inclined toward theft, mendacity, cruelty, and criminality that we can scarcely absorb the breadth of his transgressions. His supporters embrace him with religious zeal.

Advertisement

We have seen the very notion of truth eroded and tens of millions of our fellow countrypeople come to live in a world of alternative facts, conspiracy theories, fearmongering, and race-baiting—a world in which cruelty is normalized. We have seen—even after George Floyd’s murder—Tyre Nichols beaten to death by five police officers as he called for his mother and entreated that he just wanted “to go home.” We have seen in a short time the language, presence, and participation of Nazis and avowed white supremacists tolerated in public discourse. When did we lose our consensus on Nazis?

Efforts to undermine public education—first organized in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) by white parents resisting sending their children to schools with Black children—have taken a turn. Using manufactured cultural concerns about transgender people and “woke ideology,” conservative extremists are working to dismantle public education by transferring the billions of dollars that we invest in our public school system into vouchers that parents can use to send their children to private and religious schools.

Learning itself is under attack, as right-wing groups take over school boards to control what books students can read and what subjects teachers can teach. In the name of “parents’ rights,” extremists have engaged in an all-out assault on inclusivity, diversity, and equality in schools, creating an atmosphere of fear and degradation among teachers. These activists are ultimately seeking to end secular education on behalf of a version of Christianity that rejects science and treats the United States—a country formed thousands of years after the life of Christ and thousands of miles away from the place of his birth and ministry—as the only true place of God’s favor. It is a version of Christianity that tolerates, indeed encourages, hatred and dehumanization of LGBTQ people while exalting the lives of fetuses, whom its adherents call “preborn” people.

Our political system is being dismantled. The voter suppression against which I have fought since my first days as an assistant counsel at the Legal Defense Fund in the late 1980s, which remained rampant in the South, has metastasized in the decade since the Supreme Court’s disastrous decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). Now voter ID laws, burdens on absentee voting, purges of the rolls, and other restrictions have been imposed in Montana, Wisconsin, and Iowa. The new voter suppression laws seek to make electoral participation harder not only for Black, Latino, and Native American people but also for disabled voters and college students. In April a major GOP lawyer who worked on Donald Trump’s legal team and heads a right-wing think tank’s ludicrously named “election integrity network” insisted that conservatives have to work to remove polling sites from college campuses because they make it too easy for students to register and vote. Gerrymandering, meanwhile, is hastening the end of representative democracy in states across the country, unconstrained by the preclearance requirements that the Court struck down in Shelby County.

Having been allowed to gerrymander their way into supermajorities, Republican-controlled legislatures have started dispensing with the relative niceties of voter suppression and passing laws that remove power from Democratic elected state officials. You may be most familiar with Republican efforts to remove powers from progressive prosecutors in states around the country. In June the circuit attorney for St. Louis, Kim Gardner, resigned after members of the Missouri legislature, some of whom don’t even represent St. Louis, advanced legislation that would strip her of the power to prosecute violent crimes. Three months later Republicans in Georgia sought to remove power from Fani Willis, of Fulton County, to keep her from prosecuting Donald Trump for election interference. They were stopped by the state’s Republican governor, who refused to bow to the demands of the extremist voices in his party. Meanwhile, in Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis suspended Monique Worrell, an elected Democratic state attorney.*

In March Senator Mitch McConnell took a serious fall in Washington, D.C. Since then he has had several alarming public incidents in which he has appeared unable to move or speak. Five years ago the country would have been buzzing with speculation and anticipation. That’s because in most states the governor is authorized to select a replacement to finish the term of a senator who dies or steps down before their term is up. That new senator must then run to be elected to a full term. But there has been relatively little speculation about what might happen if McConnell needs to leave office, because two years ago, after he reportedly had some serious health issues, he pressed the Republican-controlled Kentucky legislature to pass a law depriving the state’s governor—a popular Democrat named Andy Beshear—of the power to appoint someone of his choice to fill a departing senator’s unexpired term. The legislature did so. Under the new law, the governor has to choose a nominee of the same party as the departing senator, from a list of potential nominees provided by the state-level executive committee of the outgoing senator’s party.

Advertisement

In other words, even if Democrats win elections at the state level, a legislature controlled by a Republican supermajority can simply strip the winner of the powers of office, leaving them with an emptied toolbox to advance the agenda for which voters elected them. The unchecked spread of this new tactic—which is made possible only by gerrymandered electoral maps—will result in a system in which elections no longer matter. It is among the phenomena that threaten most seriously to hasten the end of democracy.

And to top it off, our Supreme Court, now firmly in the hands of right-wing justices, has decided to run the table, turning back long-standing precedent and striking down rights and guarantees upon which we have come to rely. Recent revelations suggest that the Court is in an ethics scandal serious enough to call the integrity of its decision-making into question. We have learned that Harlan Crow—a wealthy and powerful Republican funder of conservative causes, including several that have come before the Court—has a long history of dispensing favors to Justice Clarence Thomas, paying for his lavish vacations and private air travel; for his mother’s home, where as of April she still lived without paying rent; and for his grandnephew’s private school tuition. Fifty years ago similar revelations would have forced a justice to resign. In 1969 Justice Abe Fortas stepped down in light of revelations that he had done work for a foundation and accepted a sum of money that pales in comparison to the sums in question now. But that was when ethics, integrity, and shame still influenced how people behaved as public servants.

Then there is Trump. He did not create racism, but he unleashed a particularly virulent brand of it, giving millions of Americans permission to be their worst selves. By exhorting crowds at his campaign rallies against Hillary Clinton to shout “Lock her up!” and promising attendees that he would pay their legal fees if they would “knock the crap out” of protesters, he normalized calls to violence in public spaces. What perhaps stuns many of us is how many Americans were looking for the release he provided: how many of our fellow countrymen and countrywomen appear to delight in the heady freedom of open racism and the intoxication of indulging misogyny, attacking gay and trans people, and breaking our hard-won social contracts. Hate crimes reached a peak in 2021. Anti-Asian violence, open antisemitism, and the steady murders of trans women, in particular, have become daily news.

Our media is largely not up to the task of dealing with the challenges we face. In pursuit of dollars and clicks, too many outlets have abdicated the essential part they play during times of democratic crisis. Even the most respected mainstream publications and news programs seem unwilling to understand how easily they have been manipulated into following red herrings since Trump appeared on the scene.

We have suffered a crisis of the spirit. Nearly three thousand people were lost on September 11, and there is not a year when we do not commemorate the anniversary with solemn services, moments of silence, and new articles or films about the dead or the survivors. But more than 1.1 million Americans have died from the Covid-19 pandemic in just three years, and we’ve scarcely taken a moment to weep together for the orphaned children, the babies left without memories of parents, the elderly who died alone, the families who waited in hallways and in the streets outside hospitals hoping to reunite with loved ones they would never see again. We have been left to mourn and cope in our own ways, with no shared worldview to unite us in collective, national grief.

We have become inundated with and inured to violence, held hostage to a uniquely American combination of white supremacy, untreated mental illness, misogyny, money in politics, and a gun culture that has come to take on the attributes of near-religious fervor. We have lived through Uvalde and Buffalo and El Paso and Tree of Life. Gun violence has saturated places like Baltimore, where I live, with young people shot in broad daylight, sometimes outside their schools. We have watched the massacre of our children—little children, high school students, college students, young adults—and have decided that we are powerless to stop it. And in those places where the population and its elected leaders have roused themselves to rein in unlimited gun access, the Supreme Court has frustrated those efforts, delivering interpretations of the Second Amendment that suggest its framers meant it to be a national suicide pact.

In 1962 James Baldwin wrote an essay about the responsibility of writers in what he called “the endeavor to remake America.” “Not everything that is faced can be changed,” he concluded, “but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” Perhaps many of us are so exhausted by the strain of the past seven or so years that we would prefer not to spend a great deal of time thinking about the full implications of what we have seen. Our democracy is mortally wounded, and many of us are in denial about the prognosis. Next year’s elections will be as consequential as any in our lifetimes. But the poor health of our democracy is not just a matter of presidential politics. Whatever the outcome in 2024, we have a great deal of work to do.

The good news is that if we make it out of this moment with the rudiments of our democracy still in place, we will be facing an opportunity that we have not had in decades: a chance to build a truly healthy democracy. Precisely because so much of what we have come to expect of our country is unraveling, because the underbelly of our democracy has been exposed, because the compromises we had come to accept no longer work, we have an opportunity to build a new America. It is an opportunity we could easily squander if we fail to see that the starkness of this moment allows us, indeed compels us, to demand more than a reversion to the old ways that left us with a profoundly unhealthy, vulnerable democracy.

This period has produced the most honest and raw conversations I have ever heard about racism and police violence. I spent decades trying to convince people that voter suppression exists. I endured countless awful conversations with movers and shakers and captains of industry who insisted that racism was over: Couldn’t I see that we elected a Black president? Now its persistence is impossible to deny.

The sudden widespread loss of the right to bodily autonomy is no longer a concept in a dystopian novel. In 2021 we watched Texas pass a law that banned abortion after six weeks and provided monetary awards to ordinary people and their lawyers for reporting anyone who helped a woman obtain an abortion. We watched the Supreme Court allow that law to go into effect and leave millions of women unable to exercise a constitutional right for nine months while the justices deliberated and wrote an opinion in another case—Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization—that struck down the right to abortion altogether. The result has been that millions of us around the country realize that our very lives and our dignity as women are at stake. We have come together to challenge state laws and provide mutual aid to women seeking abortions.

It is as though facing these kinds of threats has crystallized the stakes of our inaction. We have been reminded that the appeasements, compromises, and accommodations we have accepted have helped bring us to this point. We will only save this country, repair the damage, and create a new, resilient democracy with bold and uncompromising demands. How do we do that? Let me offer four thoughts that are guiding me as I prepare to return to the front.

First, recognize that we have been here before. This country has died and been made over at least twice. The first time was with the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments: the Thirteenth, which ended slavery; the Fourteenth, which created birthright citizenship; and the Fifteenth, which prohibited racial discrimination in voting. The Fourteenth Amendment alone was a revelation. It was created to ensure citizenship for Black people, but in the process it promised something that existed nowhere else in the Western world: if you came to this country and had a child here, your child would be a citizen from the moment they were born. It established that anyone is entitled to due process and equal protection under the law. And it included powerful enforcement clauses. Any state that interfered with the voting rights of men, “except for participation in rebellion, or other crime,” one section stipulates, would have its “basis of representation…reduced in the proportion” to the number of people it had disenfranchised.

These three amendments were designed to create a new nation. When we talk about the framers, we talk about Hamilton and Madison and Jefferson and Washington, but we should also talk about the framers of the new America after the Civil War: John Bingham and Charles Sumner and Frederick Douglass and many others who envisioned a nation in which equality and justice would be the standard. The authors of these new amendments were explicit about who would have the power to protect the rights they promised. All three Reconstruction Amendments contain almost identical provisions to the effect that “Congress shall have power” to enforce their guarantees “by appropriate legislation.” That’s how we ended up with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. These amendments, taken together, amounted to an opportunity to reset the country.

That opportunity was stolen by white supremacist violence; by the Supreme Court, which turned its back on the Reconstruction Amendments in rulings including US v. Cruikshank (1876), the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896); and by Congress, which for over sixty years after Plessy sat on its hands, passed none of the civil rights laws the Reconstruction Amendments authorized it to, and remained mute when the Supreme Court stripped power from the civil rights statutes it had passed immediately after the Civil War. Congress awakened again only in the second half of the twentieth century, under pressure from a growing civil rights movement.

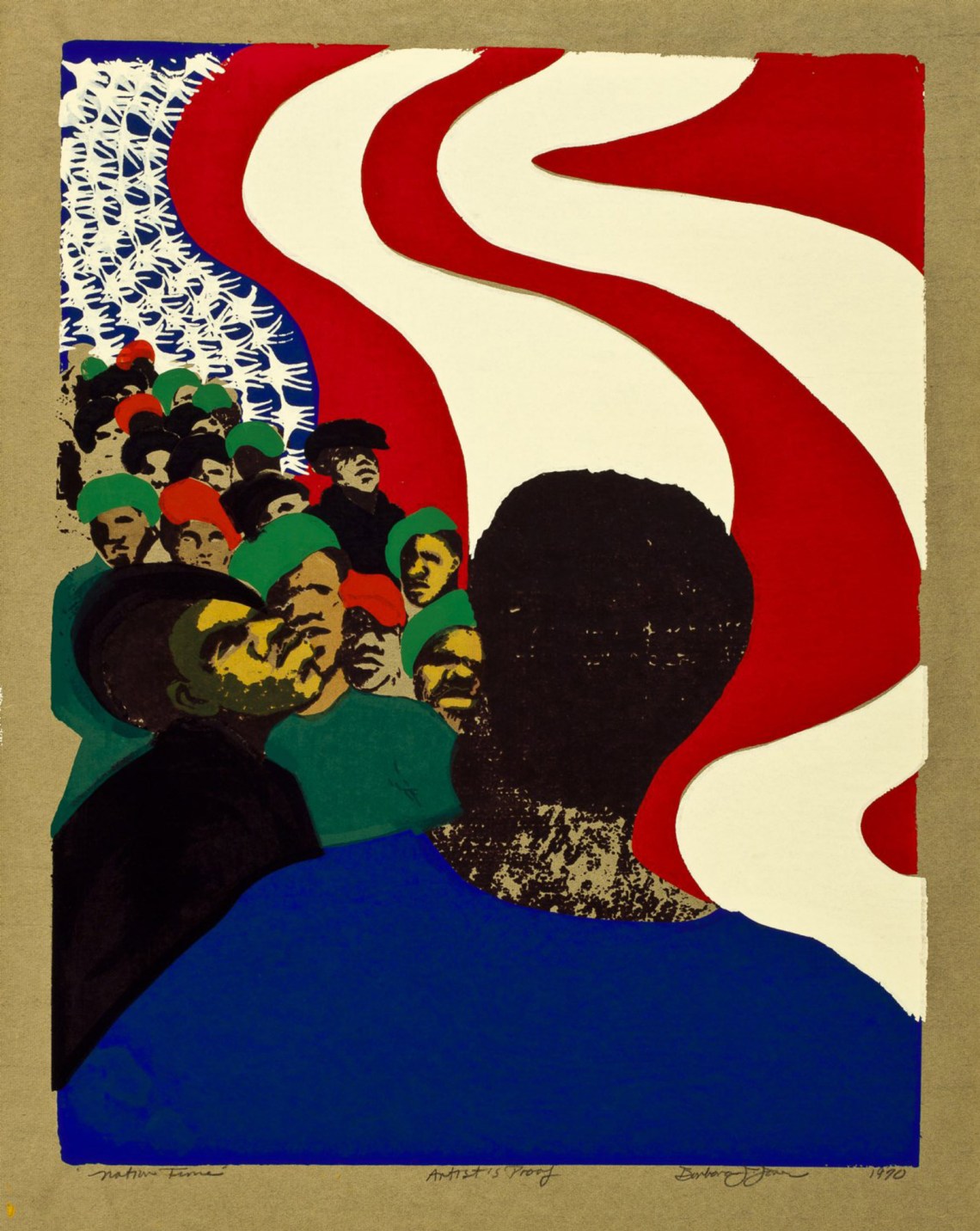

This was the second time our country was recreated. The people responsible were not principally the legislators who drafted or passed civil rights statutes. They were ordinary people who pressured the courts, Congress, and the president to act. Their names were Thurgood Marshall, Charles Hamilton Houston, Pauli Murray, Constance Baker Motley, John Lewis, Bob Moses, Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael, Mickey Schwerner, James Reeb, Rosa Parks. These were people who still lived as second-class citizens in this country, the very people to whom America had broken its promises. And yet they executed a vision of what it could look like if we lived up to the ideals of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.

Their actions are responsible for the lives many of us have been privileged to live. I’m not talking just about Black people. I’m talking about everyone. Their litigation and activism laid the foundation to allow women to do what women have been able to do, to allow you to marry whom you wish to marry, or have access to jobs across wide sectors of the economy. The elimination of those barriers opened up educational opportunities, intimate partner relationships, and broader civic interaction to a wide swath of white, Latino, and Asian American men as well, who were also subject to arbitrary rules and prohibitions designed to perpetuate bias and stereotypes.

The second thought guiding me is that we have to diagnose the sources of the challenges we’re facing. It’s fashionable for those of us working for equality, inclusion, and democracy to lament that we haven’t been strategic enough. But perhaps we are being too hard on ourselves. I have come to believe that we are facing such strong opposition precisely because we have won so much.

In the decades following the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, and the women’s movement, we have effectively reset the cultural, social, and political life of this country from the patriarchal and white supremacist standards that dominated American life in the early 1950s. Now we are seeing the backlash. Why are they banning The Diary of Anne Frank and books about Rosa Parks? (Yes!) Because they understand that empathy is one of the strongest, most consequential tools in a democracy. We all bore witness to that fact when millions of people took to the streets in the middle of a pandemic after seeing the torture and murder of George Floyd. That video generated the largest civil rights demonstrations in this country’s history. The protests were multiracial. They occurred in all fifty states and then around the world. That display of power, that burgeoning swell of solidarity, also generated the fear that has motivated recent efforts to ban books and undermine protests—including a Florida law that would grant immunity to motorists who drive into crowds of protesters.

The recent upsurge in voter suppression bills is likewise a response to the resilience that voters showed in 2020, especially Black voters, who cast the last ballot in the presidential primary in Harris County, Texas, at 1 AM and stood on line in Fulton County, Georgia, for nine hours to vote early in the general election. Georgia’s Republicans soon after passed a law criminalizing the provision of refreshments to people standing on line to vote. (It was subsequently narrowed by a federal judge.) It is critical for us to understand that this wave of repression is a response to our demonstrations of power. We must not prematurely abandon the actions that have so frightened our opponents. This is not the time to give up empathy or solidarity, to stop voting or marching or organizing.

Third, we need to embrace better sources of information. When I left law school I worked for a year as a fellow at the ACLU’s Reproductive Rights Project. One of the cases that I worked on was Rust v. Sullivan, in which we challenged a law created by the Reagan administration forbidding federally funded family planning clinics from counseling their patients on abortion. We called it the gag rule. The team of brilliant women lawyers who were handling litigation for the project took our challenge to the Supreme Court, where we lost.

My job was to help prepare our complaint by visiting family planning clinics to gather information and get affidavits from staff and patients about the gag rule’s potential effect on the integrity of the care they would give or receive. I visited clinics throughout New York and New Jersey, where I listened to mostly young women explain how they used Planned Parenthood, how much they relied on its clinics and doctors for reliable information, and how important it was to their health. I knew this myself, because at the time I utilized a Planned Parenthood clinic in Lower Manhattan for reproductive care. Indeed, the doctor who showed tremendous courage in agreeing to become the plaintiff in our case, a brilliant and committed Black man named Irving Rust, worked at the clinic I used.

We understood then that restrictions on abortion rights would come soonest to poor women, and disproportionately Black and Latina women—first with the Hyde Amendment, which barred the use of federal funds to pay for abortions, and then with the gag rule. But at the time many of us warned that these restrictions would not be limited to poor women and women of color, that those communities were merely the staging ground for broader restrictions. I recall many “experts” pushing back. The right to privacy, they insisted, had by then become inviolable, deeply ensconced, connected to so many other rights. And yet here we are. Are we listening to the right voices, the ones telling us where our democracy is weak?

Finally, we need to pursue power, and when we have power we need to be prepared to make transformative change. I hope we’ll see this in the coming years. We must be prepared to leave behind traditions and policies that have not served us as a democracy, whether that means reforming long-standing rules that inhibit effective representation in the Senate, or adding seats to the Supreme Court, or reimagining public safety to address police brutality and racism, or adopting a guaranteed national income, or pursuing new models of public education.

Progressive people often seem averse to the pursuit of power. It is as though we think “power” is a bad word. We think it unseemly. We worry, perhaps appropriately, about how power can corrupt and harm. But that is what happens when people abuse their power. It is not power’s natural tendency. We must believe enough in our own integrity to trust ourselves with power. “Power without love is reckless and abusive,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, and

love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.

We must pursue power to implement the demands of justice, and the justice that we seek must correct that which stands against love. I pray, encourage, and entreat you to join me and so many others who are committed to this struggle. I know that we can win, but only if we truly engage the fight.

This Issue

December 21, 2023

A Bitter Season in the West Bank

A New Language of Modern Art

-

*

For a longer discussion of these and other cases, see my “The Republican Plan to Make Voting Irrelevant,” Slate, March 24, 2023. ↩