Sometime around 1520 Ferdinand Columbus, second son of the famous Christopher, wrote to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (Charles I of Spain), requesting money for a universal library—a place, Ferdinand explained, where “all the books will be gathered, in every language, and concerning all the sciences and the arts that can be found both in Christian and in non-Christian nations.” Attached to the court since childhood, Ferdinand had accompanied his father on his calamitous fourth voyage as a teenager, but then devoted himself to a life of scholarship and diplomacy. Crisscrossing Europe on missions for the crown, he amassed more than 15,000 books and 3,200 prints, the most complete repository of verbal and visual information in Europe.

The five hundred livres that Charles V eventually coughed up aside, this extraordinary venture was made possible by Ferdinand’s own fortune, which is to say by the New World holdings granted to his father, which is to say by colonial crimes of the first order—theft, slavery, genocide. Ferdinand himself seems to have been a thoughtful man, and it is easy to be moved by the sublimity of his aspirations. It is also easy to condemn the atrocities and cultural obliteration on which they depended. What’s difficult is holding both in your mind at the same time.

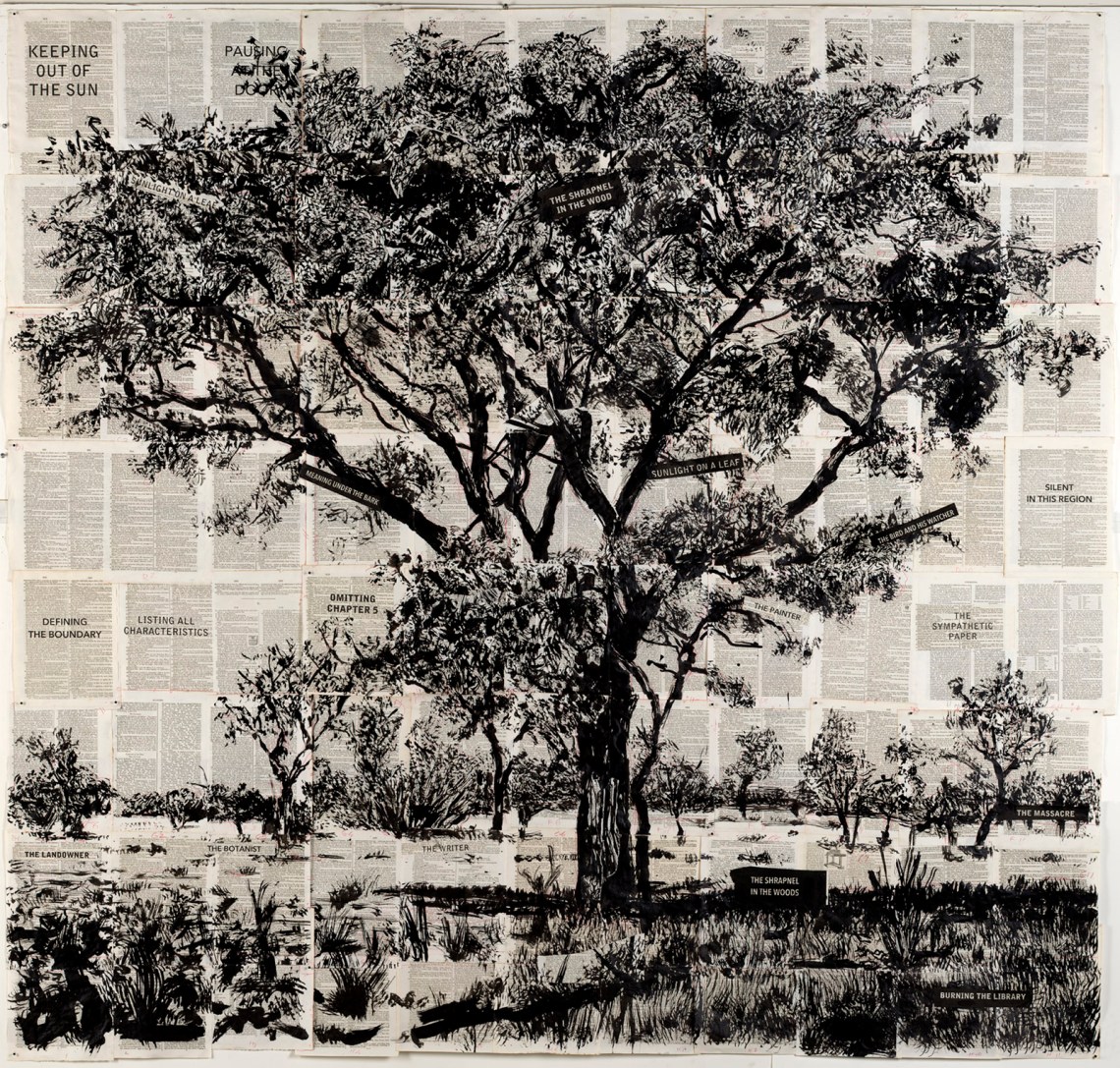

This is the essential quandary William Kentridge has spent his career voicing through art: How do we reckon with both the radiant promise of knowledge and its effects as an engine of subjugation and destruction? Is there a border where the desire to know becomes the will to control, or do they slide down the slippery slope hand in hand? Kentridge, who was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1955, the son of anti-apartheid lawyers, came of age within a vividly brutal example of pseudoscientific thinking run amok. The lessons he took from it were both historically specific and philosophically broad—chief among them: Nothing is as simple as it looks.

The South African literary scholar Stephen Clingman opens his text for the recent Kentridge retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts in London with images of his thirteen-foot-tall sculpture World on Its Hind Legs (2009). Seen head on, it looks like a giant ink drawing of a globe perched on a pair of inverted radio masts. Step to the side, however, and the amiable, cartoonish globe reveals itself as a concatenation of black metal jutting into space with the confident aggression of a Mark di Suvero sculpture or a guy manspreading on a subway seat. Both views are real; it just depends on where you stand.

Such eye-grabbing theatrics and tangible metaphors have made Kentridge one of the twenty-first century’s most visible artists. In addition to being represented in just about every relevant museum you can think of, he has delivered the Norton Lectures at Harvard, produced operas for the Met, and designed espresso cups for Illy. In the past year he has been the subject of two major retrospectives—one at the RA and another, “William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows,” at the Broad in Los Angeles and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; his large-scale music/theater works have been presented in Los Angeles, Paris, Johannesburg, Madrid, and Vienna; Steidl in Germany has published a catalogue raisonné of his early prints and posters (weighing in at a hefty ten pounds); Seagull Books in Kolkata has released an artist’s book of found phrases he collects in his studio; and Marian Goodman Gallery recently hosted the New York premiere of his new multichannel video installation, Oh to Believe in Another World.