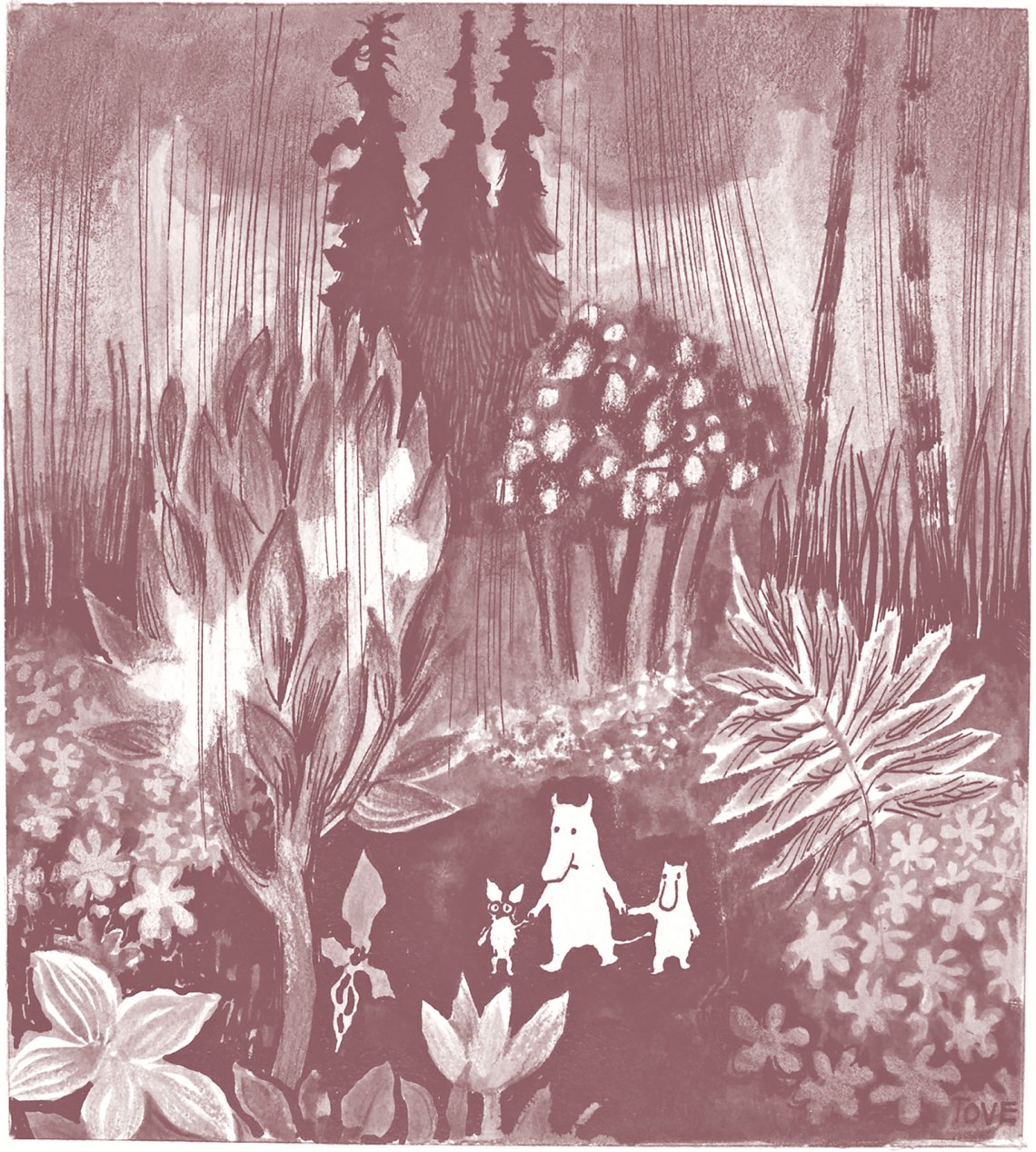

Scandinoir was born in November 1939, when the Soviet Army invaded Finland and the Finnish artist and writer Tove Jansson wrote a story in which a mother and child find themselves in a wood: “Once upon a time a Moomintroll was walking with his mother through a very strange forest.” When the story was published in 1945 as Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (The Moomins and the Great Flood), this opening was revised so that the creatures are no longer walking, and the events begin in darkness:

It must have been late in the afternoon one day at the end of August when Moomintroll and his mother arrived at the deepest part of the great forest.

It was completely quiet, and so dim between the trees that it was as though twilight had already fallen. Here and there giant flowers grew, glowing with a peculiar light like flickering lamps, and furthest in among the shadows moved tiny dots of cold green.

“Life is just waiting now,” Jansson said of the war years. “One isn’t really living, one just exists.”

The Moomins, when we first meet them, are similarly suspended, half-awake, half-asleep, motionless in the middle of things. The simple-seeming sentences carry a good deal of freight. We know, for example, the quality of the dark, the density of the silence, the month of the year, and the hour of the day, but the most important information is elided. Where have Moomintroll and his mother arrived from? Children, Jansson believed, are “spellbound by what is unspoken,” and children’s books “should have a path…where the writer stops and the child goes on. A threat or a delight that can never be explained. A face never completely revealed.”

Late August, Jansson observed in Finn Family Moomintroll, is a time of year when “there was expectation and a certain sadness in the air…. Moomintroll had always liked those last weeks of summer most, but he didn’t really know why.” Jansson was born in August, but August was also, she said, “the border between summer and autumn,” just as twilight was “the border between day and night”; the border was “longing,” and to be on the border was “to be on the way.” Jansson herself lived on the border: she was half-Swedish and half-Finnish, half-artist and half-author, a lover first of men and then of women. Half her year was spent in her overloaded Helsinki studio and the other half on the simple and isolated island in the Gulf of Finland where she tried to disappear.

A border can be breached, and the horror of the Winter War, as the 1939 attack was called—when 300,000 Finns were made homeless and the country responded with the kind of ferocity currently shown by Ukraine—provides the warp and weft of the first Moomin book. Moominmamma and her son are searching for somewhere to hibernate, but they are also searching for Moominpappa, who has disappeared. He is either lost, or dead, or now “mostly invisible” like the deaf and mute Hattifatteners, fungus-like creatures with whom he has wandered off. Seeing two eyes staring at him from behind a tree, Moomintroll stiffens with fear, but the eyes belong to “really a very little creature” who is equally scared. “What sort of thing are you?” asks the little creature, a cross between a rat and A.A. Milne’s Roo. At this point in his evolution, Moomintroll looks less like the hippo-shaped thing he will grow into than Edward Lear’s Dong with the Luminous Nose.

We might ask the same question of The Moomins and the Great Flood, a book of forty-eight pages with anguished illustrations in sepia watercolor and scratchy black ink. (Jansson was unable, during the war, to think in color.) What sort of thing was this? She called it a “fairy tale,” which is not quite right. “Poe calls his things ‘tales,’” said D.H. Lawrence, much as Pound called Lawrence’s tales “somethings.” Jansson’s “thing” was neither a long tale nor a short tale but a small tale—a tale concerned with the security, when under threat, of smallness.

Written in Swedish and published in Sweden in an abbreviated version (a Finnish translation did not appear until 1991), the book went unnoticed, selling only 219 copies in 1946. Being unnoticed, however, is what Moomintrolls prefer. “I hope we’re so small that we won’t be noticed if something dangerous should come along,” says Moominmamma. “We are so small that we wouldn’t be noticed,” Moomintroll reassures the little creature, who in the second book in the series, Comet in Moominland (1946), is given the name Sniff. It is easy to forget how small the Moomintrolls actually are: the illustrations show them dwarfed by the glowing tulip they carry as a torch and the lily pad they use for a boat.

Advertisement

In Sculptor’s Daughter (1968), her collection of autobiographical somethings, Jansson returns to the safety of smallness. “Maybe nothing is so important provided that it is small enough,” she writes in the story “Flotsam and Jetsam.” “You make yourself very small,” she says in “The Stone,” “shut your eyes tight and say a big word over and over again until you’re safe.” In “Jeremiah” she recalls playing hide-and-seek with a visiting geologist: “He had to take a long time to find me and to discover how terribly tiny I was. I tried to make myself smaller and smaller so that he would be delighted.” The best way of all to be safe, she explains in “The Dark,” is “to sit high up in a tree, that is if one isn’t still inside one’s Mummy’s tummy.” Moominmamma’s tummy, which is flat in the illustrations for The Great Flood, grows larger and rounder in the later books, its safety emphasized by a fresh white apron.

Together with the little creature and Tulippa, a blue-haired girl who lives in a flower, Moominmamma and Moomintroll cross a swamp containing a Great Serpent, ride an escalator to a sky-garden kept by a kindly old man, get caught in a biblical deluge, and rescue Moominpappa from high up in a tree he has climbed to escape the rising water. Because his newly built house has floated, ark-like, into a lush vale, the reunited family can begin anew: Jansson’s intention was to give her readers a happy ending. “Now we shall never be separated again,” says a tearful Moominmamma. By the eighth book, Moominpappa at Sea (1965), when the family discover they can live neither with nor without one another, her promise has become a curse. Jansson, similarly bound to the Moomins for life, was also longing to separate. “I could vomit over Moomintroll,” she wrote in her notebook in the late 1950s. But the more she hated her creation, the better the books became.

Tove Jansson had lived with the Moomins since childhood, when her maternal uncle scared her with tales about the “Moo-oo-min trolls” behind the stove who would blow on her neck if she stole from the larder. Having initially imagined them as “house ghosts,” Tove drew her first Moomintroll—the “ugliest thing” she could think of—on the bathroom wall, in order to illustrate a point about Immanuel Kant; next to it she scrawled “Freedom is the best thing,” from the Swedish medieval poem “Song of Freedom,” and underneath she wrote “Snork,” the original name for the Moomintrolls. In other early illustrations Moomins have black rather than white fur; by her early twenties, when she had become a cartoonist, a Moomin-shaped thing served as what she called her “angry signature character.” The Moomin anger, once their defining feature, has vanished in The Great Flood, where their most striking feature is fear.

The Moomins and the Great Flood is an origin story whose own origin lies in other stories, specifically those told to Jansson by her mother, Signe Hammarsten, known as Ham. “Mummy’s stories are often about Moses—in the bulrushes and later,” Jansson wrote in Sculptor’s Daughter,

about Isaac and about people who are homesick for their own country or get lost and then find their way again; about Eve and the Serpent in Paradise and great storms that die away in the end. Most of the people are homesick anyway, and a little lonely, and they hide themselves in their hair and are turned into flowers.

Visually, The Great Flood seems to be set inside a picture by John Bauer, the Swedish painter and illustrator whose trolls and muted palettes were revered by Jansson’s generation. Bauer was the only artist, said Ham, who knew how to draw a forest. To show its immensity, “you don’t include the tops of the trees or any sky. Just very thick tree-trunks growing absolutely straight”; the color of the moss, trunks, and branches should be “between grey and brown and green, but very little green. If you want you can add a princess.”

The wood in The Great Flood is also Dante’s, and the plot itself is borrowed from In Search of the Castaways by Jules Verne. The blue-haired girl is born of Pinocchio, Thumbelina, and Alice in Wonderland (later illustrated by Jansson for Åke Runnquist’s Swedish translation in 1966), while the “mostly invisible” Hattifatteners descend from Edward Lear’s Jumblies, who went to sea in a sieve (they did). In later books Jansson will play with elements from Shakespeare, Defoe, Coleridge, Kipling, Conrad, Lawrence, Poe, Woolf, and Beckett; Moominpappa at Sea, for example, is a reworking of Robinson Crusoe, Typhoon, The Tempest, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” To the Lighthouse, Poe’s unfinished story “The Light-House,” and Lawrence’s masterpiece, “The Man Who Loved Islands.” Small books bearing great burdens, the Moomins contain the whole arsenal of Western literature, and so it is strange that they are associated with an entirely homespun Finnish whimsy.

Advertisement

Tove Jansson, born in Helsinki in 1914, was conceived in Paris, where her mother was studying painting and her father sculpture. An artist’s place of conception is not always worth mentioning, but Jansson, who was inordinately interested in her mummy’s tummy, returned to Paris in her early twenties to follow in her parents’ footsteps. Her father, Victor Jansson (“Faffan”), who came home from the war in 1918 a broken man, was a Finnish sculptor from the Swedish-speaking minority, and Ham, the daughter of a Swedish clergyman, became a well-known draftswoman and caricaturist. Part-bohemian, part-patriarch, Faffan believed in Finland, family, and the importance of art. “Home and studio were one,” writes Boel Westin in her adoring biography, Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words, “with no clear distinction between work and family life.” The home, filled with plaster dust, clay, paintings, and floor-to-ceiling books, was like “a box with endless secret compartments,” and because there was no room for a bed, Tove slept on a shelf.

In the summer the family decamped to a cabin in the Pellinge archipelago, where Faffan’s melancholy disappeared only when he took his children out in a storm. “Damn it!” shouts the father in Jansson’s autobiographical story “The Bays”:

Can you imagine what’s happened! The water has risen nearly two feet in the boathouse! The clay looks like porridge. It’s a damned nuisance, but there’s nothing to be done about it…I’ve no time for tea now. I’ll be back later.

“I want to be a wild thing, not an artist,” Tove confessed in a childhood diary. She became both, her ambivalence toward her family fueling her art. Faffan’s sculptures could not support them and so, to his humiliation, Ham became the breadwinner and Tove stepped in to help when she was fourteen, collaborating with her mother on stories for the Swedish-language magazine Garm and standing in for her when Ham’s own mother was dying. Having wanted to paint, Tove became instead an “Indian ink machine,” producing cartoons, comic strips, caricatures, book covers, and illustrated poems and stories. “Am I to let mother slave alone?” she asked her diary when she started at Stockholm Technical School in 1931. “Nothing could be more hateful to me than causing you unnecessary financial worries,” she wrote to her parents two years later.

During the war, when Faffan fervently supported Germany, Jansson drew satires of Hitler and Stalin for the cover of Garm. “Faffan and I have said we hate each other,” she told her friend Eva Konikoff. “It’s hell to be still living at home here.” In Family (1942), the oil painting that she considered her first significant canvas, the Janssons are frozen in their own thoughts. Tove, tense in a black coat and hat as if waiting to go out, is imprisoned between Ham and Faffan, who are looking in different directions; in the foreground her younger brothers, Lars and Per Olov—in his soldier’s uniform—are lost in a game of chess. It is a portrait of a woman who can never leave home because family will always come first. “Every still-life, every landscape, every canvas is a self-portrait!!” she wrote to Eva.

Her lovers were initially men, including the Communist philosopher Atos Wirtanen, who shared her politics, but in her thirties she moved to what she called “the spook side.” Jansson’s lesbianism, known to her friends, was never acknowledged by her parents: “Ham said nothing. She never says anything. I think she knows. But she doesn’t want to mention it. I can accept that this is right and more elegant. But it feels lonely.” Homosexuality was illegal in Finland until 1971, and Jansson made herself as small as possible so as not to be noticed. “We are so few!” she told Eva.

The Comet Hunt (1946, published in English in 1951 as Comet in Moominland), which sold 246 copies in its first year, is a response to the Soviet bombing of Helsinki and the American bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story begins several weeks after the family reunion, with the Moomins settling into their house in the valley: Moominpappa is building a bridge, Moomintroll is putting up a swing, and Sniff—now an honorary Moomin—is following the forest paths. As in the Jansson household, work and play in Moominvalley are indistinguishable. The creatures who seemed, in The Great Flood, to be sleepwalking through the forest are now fully awake and fixed in their roles.

New characters include a cackling silk-monkey; a muskrat who preaches the Uselessness of Everything; the Snork Maiden, who likes looking at herself in the mirror; Snufkin, a pipe-smoking tramp—inspired by Wirtanen—with a mouth organ; and two gloomy Hemulens, one of whom is interested only in collecting butterflies, the other only in collecting stamps. A Hemulen, physically similar to a Moomin, does not understand play. Obsessed with details and law and order, they work as park rangers, policemen, and matrons of orphanages; unless they are in uniform, Hemulens wear long dresses that they hate to remove.

Moominvalley is not, like the world Alice finds through the looking glass, nonsensical or inside out. It is a rational place whose strangeness is neither exaggerated nor explained, because everyone’s philosophies, compulsions, obsessions, paranoias, and neuroses make sense to them and to everyone else. It reminds me of Grasmere Vale, the verdant paradise where Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy, relived their own lost childhood.

When a comet is seen “diving headlong” toward the Earth, the Moomins and their friends wait in a cave for the world to end, scheduled for the seventh of October at 8:42 PM:

There was a rush of air as if a million rockets were being let off at once, and the earth shook. The Hemulen fell on his face among the stamps, Sniff yelled at the top of his voice, and Snufkin pulled his hat even farther over his nose for protection.

In the final chapter, when there appears to be no escape from extinction, the fireball flicks its tail over the valley and hurtles onward, “over the edge of the world. If it had come a tiny bit nearer to the earth I am quite sure that none of us would be here now.” It is an astonishingly daring story: the only time I have felt a similar terror was watching Lars von Trier’s Melancholia in 2011.

The first two Moomin books are apocalyptic and the next three are comedies. “Before the war,” Jansson explained, “I used to think the purpose of life was to act as justly as possible; after the war I thought the purpose of life was to be as happy as possible.” Finn Family Moomintroll (1948), the first of the books to be translated into English (in 1950), was a celebration of Jansson’s first lesbian relationship, with the theater director Vivica Bandler: “O, to be a newly-woken Moomintroll dancing in the glass-green waves while the sun is rising.” The black-and-white illustrations look like etchings or Japanese floating-world prints, but the world they describe is technicolor.

Tove and Vivica appear as the inseparable twins Thingumy and Bob, who speak a language no one understands, sleep together in a drawer, and carry a suitcase whose secret contents turn out to be a ruby compounded of many colors: “At first it was quite pale, and then suddenly a pink glow would flow over it like the sunrise on a snow-capped mountain—and then again crimson flames shot out of its heart.” The sexual coding is there for anyone who wants to see it. Moomintroll, who rarely has the words to describe what he is thinking, looks at the jewel “so long it seemed that time grew weary, and his thoughts were very big.”

In The Exploits of Moominpappa (1950; revised in 1968 as The Memoirs of Moominpappa), Jansson satirized Faffan’s self-importance. “You are a young poet nobody understands,” a hedgehog tells Moominpappa, “so naturally it would be really good to understand you.” Moominpappa’s bildungsroman is a work of plagiarism, lifted from David Copperfield, Joseph Conrad’s Youth, Cellini’s Life, and “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” If Coleridge had a “smack of Hamlet,” Moominpappa has a smack of Coleridge, whose “painted boat upon a painted ocean” becomes Moominpappa’s Oshun Oxtra, a “ghost ship” caught in a “little toy gale.” “The sun was gone,” Moominpappa reads aloud from his latest chapter:

The horizon was gone. All was different, strange, and inimical. Hissing specks of white foam from the waves were flying past us, and beyond the railing everything was black, inconceivable chaos. Suddenly I understood with blinding insight that I didn’t know anything about sea or about ships…I was alone and totally deserted, and it was of no help to be in the midst of an unquestionably Highly Dramatic happening.

The Memoirs conclude with Moominmamma and her handbag floating to the shore on a spray of foam, like Aphrodite on her scallop shell. “When people read this book,” says Moomintroll as his father looks up from the page in proud silence, “they are going to believe that you are famous.”

In September 1954 the London Evening News began publishing the daily comic strips that established Jansson’s fame (reissued in 2014 and 2019 in two volumes by Drawn and Quarterly). The Evening News (with a circulation of 12 million) was the world’s biggest daily newspaper; by 1956 the strips were being syndicated in twenty other countries; at their peak they appeared in 120 daily papers. Jansson hoped the income would buy her time for painting, but the pressure to produce copy became a constant “toothache.” The cartoons, in which the Moomins grapple like Jacques Tati characters with the bewilderments of hotels, winter sports, and unwanted guests, are funnier than the books, but they also serve a therapeutic purpose. By focusing less on plot than on what she called “psychological moments”—the experience of loneliness, unrequited love, insecurity, fear, separation, jealousy, and grief—Jansson was seen by her readers as someone who understood their inner lives.

She described the Moomin books as abreactions, a Freudian term for emotional release, but returning to them after a gap of fifty years it strikes me that they also explore the psychotherapist Donald Winnicott’s radical views of the child, the family, and society. Winnicott’s theory of creativity as play, and of play as an expression of the “true self,” is the Moomin philosophy, while Moominvalley is what Winnicott called a maternal “holding environment.” While Winnicott may not have read Jansson, Jansson—who by the mid-1950s had become Finland’s therapist and by the 1960s was undergoing therapy herself—appears deeply conversant with Winnicott.

By the mid-1950s, Finnish homes were turning into a version of Moominvalley. Department stores in Helsinki stocked Moomin-themed aprons, skirts, curtain fabrics, wallpaper, crockery, and pens as well as Moomins modeled in marzipan, ceramic, and leather. Artistic control was maintained, down to the finest detail, by Jansson herself, who turned down the idea of Moomin sanitary towels. “Every time I think I glimpse a ray of hope,” Jansson said of her new life as a coordinator of Moomin merchandise, “a new avalanche of things needing attention descends to block the light.” While Japanese people embraced the Moomintrolls, Americans remained largely immune, possibly because Jansson refused the Bobbs-Merrill Company’s request for exclusive rights to the word “Moomin” and the offer of a deal with Disney. Last year, however, Barnes and Noble partnered with Moomin Characters Oy Ltd. to promote the brand in their shops, so Moomin mugs, Moomin notebooks, and Moomin “house goods” are now available at a store near you.

Having hoped they might be small enough to go unnoticed, the Moomins had become huge. Why did Jansson allow the commercialization of her psychologically subtle and profoundly personal work? How could she bear for her wisdom to be marketed as self-help? Why did she not get a secretary to help reply to the two thousand fan letters she received every year from people “I don’t know and don’t like”? (“Hi my name is Olavi. You write well but last time you didn’t make a happy ending. Why do you do this?”) Nothing in Westin’s biography explains the complexity of Jansson’s character or her ambivalent relation to fame, but Moominsummer Madness (1954), a spin on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, appeared in the midst of this Moominmania. Once again flooded out of their home, the Moomins take refuge in a floating theater where Moominpappa tries his hand at a blank verse tragedy called “The Lion’s Brides, or Blood Will Out.” Having never seen a theater before, they learn that it is a place “where people show what they could be, and what they long to be even though they can’t be, and how they are.”

It was Jansson’s life partner, Tuulikki Pietilä, who suggested that the seventh book, Moominland Midwinter (1957), should explore “what it is like when things get difficult.” This is the first of Jansson’s two great tragedies. Waking from his hibernation three months early, Moomintroll cannot get back to sleep. Moominmamma turns away when he tries to wake her, and the house is buried beneath an avalanche of snow that blocks the light.

As profound a study of depression as Charlotte Brontë’s Villette, Jansson’s “winter’s tale” is also about living on the spook side. Tuulikki appears as the practical Too-ticky, who—with a party of other “winter people,” including invisible shrews and an “ancestor” who is (literally) in the closet—takes over the boathouse every year while the Moomins are asleep.

“Have you read ‘The Man Who Loved Islands’?” Jansson wrote to Tuulikki in 1963. “How about the woman who fell in love with an island?” In the D.H. Lawrence story, a misanthrope named Cathcart moves from island to island, but none is small enough or empty enough for him. Eventually, as the sole inhabitant of a remote rock, he climbs to the top of a hill. “He pretended to imagine he saw the wink of a sail. Because he knew too well there would never again be a sail on that stark sea.”

In 1947 Jansson and her brother Lars bought the island of Bredskär, hoping to spend time there alone. When it became overrun by family she and Tuulikki built, in 1963, a house on the “angry little skerry” of Klovharu, which could be circumnavigated in four and a half minutes. Here she was pursued by boatloads of fans: “Seventeen strangers came from E. to have coffee, drinks and soft drinks and talk and ‘look at me,’” she wrote in her diary. “Kiss my arse…. Threw stones. Angry.”

The last two Moomin books, written on Klovharu, are absurdist dramas. In Moominpappa at Sea (1965), Moominpappa—feeling himself a failed artist—moves the family, together with the anarchic Little My (the “wild thing” Jansson wanted to be), to an island that is “completely silent and terribly, terribly old.”

It was virtually deserted. There was a lighthouse, but the light had gone out. There was a fisherman living there on the headland, but he kept silent. To this island Moominpappa brought his family, wanting to guard and protect them.

Sniff, Snufkin, the Snork Maiden, and the Moomins’ other friends have vanished, together with the Moomin pleasure principle. The once happily extended family is now a tight nuclear unit, fuming in silent rage. Climbing into the mural of Moominvalley that she has painted on the wall, Moominmamma spies on her husband and children. “Well, that really is the last word in madness,” says Little My, whose arch commentary keeps up the narrative tempo. Moomintroll becomes fixated on a seahorse he can’t tell apart from her twin, both of whom mock him as a mamma’s boy. Little My suggests they should all express their feelings but, like the family in Jansson’s 1942 painting, they are yoked in silence. Moominpappa does nothing, as his family falls to pieces, to guard and protect them.

The island, shrinking with unhappiness, watches its inhabitants, and the sea mocks them. If he could only understand the ocean, Moominpappa reasons, then “everything would fall into place.” Like Lear, he howls at the elements; like Canute, he tries to control the waves; he rolls impossibly large rocks to make a breakwater that is instantly destroyed. By the final chapter there is no sign that the Moomins will ever return to Moominvalley. Jansson confessed she had “abreacted hugely through this book.”

As the popularity of the Moomins increased, their visibility in the books decreased, and they eventually disappeared altogether. The events, or rather nonevents, of the final tale, Moominvalley in November (1970)—written as Ham was dying—take place in Moominvalley while the family is on its island. Various creatures, including Snufkin, a Hemulen, and an orphan named Toft, invite themselves to stay with the Moomins only to find that they have left the valley without saying good-bye. After waiting in vain for their hosts to return, the visitors leave. Only Toft, who has yearned all his life for the love of Moominmamma and feels “deceived” by her departure, continues to wait, and it is with his waiting that the book concludes.

The fans who gathered in groups to read Moominvalley in November felt similarly “angry, disappointed, cheated” by the Godot-like finale to the series. But there is a narrative consistency to the Moomin books, whose subject throughout is homesickness and which open and close with the self-absorption of a melancholic father.

Freed, at fifty-six, of her Frankenstein’s monster, Jansson wrote The Summer Book (1972), which she called her favorite. Critics agree that it is her masterpiece, and I admire it for its loose-limbed ferocity. It is set on a tiny island over a series of summers. A frail artist and her granddaughter, Sophia—whose remote father is rarely seen—play, squabble, explore the forest, and cowrite A Study of Angleworms That Have Come Apart. “When are you going to die?” Sophia asks her grandmother. “Soon,” the old woman replies. “But that’s not the least concern of yours.” Later, the grandmother finds a note under her door that reads:

I hate you. With warm personal wishes,

Sophia.

This Issue

January 18, 2024

Bodies That Flow

Tools to End the Poverty Pandemic