Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “Averroës’ Search” begins one afternoon in twelfth-century Andalusia, in the shady Cordovan home of Ibn Rushd, later known in Europe as Averroës. The philosopher is at an impasse in his commentary on Aristotle’s Poetics: two words, “tragedy” and “comedy,” are everywhere in the Greek but opaque to the Arab, who has no notion of dramaturgy. At a dinner party that evening, the subject of poetry comes up again: a guest argues that the Bedouin verse of pre-Islamic times, the foundation of Arabic literature, is obsolete for poets living in sophisticated cities like Córdoba. When the sixth-century poet Zuhayr compared destiny to a blind camel, the metaphor was arresting; now it seems absurd.

The philosopher disagrees. He argues, in perfectly Aristotelian fashion, that poetry deals in universals: its purpose isn’t to amaze but to invent figures understandable by everyone. (Borges’s sly implication seems to be that the powerful yet clumsy camel, against whom all human struggle is doomed, points toward an Arabic translation of “tragedy,” even if Ibn Rushd doesn’t realize it.) Because of poetry’s universalism, the philosopher continues, the passage of time enriches it rather than making it out of date. Recalling Zuhayr’s verse now, we not only think of his metaphor but compare our struggles with his: “The figure had two terms; today, it has four.” Ibn Rushd finishes with an anecdote. During a stay in North Africa, “tortured by memories of Córdoba,” he was consoled by a line of poetry composed by the caliph ‘Abd al-Rahman, who addressed a tree in his royal garden while thinking of home in Damascus: “Thou too art, oh palm!,/On this foreign soil…”

Ibn Rushd’s dinner companions would have known all about ‘Abd al-Rahman. A member of the Umayyad family, which ruled the second Islamic caliphate from Damascus between 661 and 750, he escaped the slaughter of his kin by the rival Abbasids and fled west. In 756 he proclaimed Umayyad rule over the Iberian Peninsula—al-Andalus, in Arabic—which his descendants would govern from Córdoba for nearly three centuries. Many things in the new capital harked back to ‘Abd al-Rahman’s native Syria: his estate of al-Rusafa, with its transplanted palms, bore the same name as a royal compound near Damascus; the prayer niche of his great mosque faced south, like those of Syria, though of course Mecca lies east of Córdoba. “A remarkable gift, the gift bestowed by poetry,” Ibn Rushd reflects in Borges’s story. “Words written by a king homesick for the Orient served to comfort me when I was far away in Africa, homesick for Spain.”

In Arab literary history, the memory of al-Andalus survives like the transplanted palm of ‘Abd al-Rahman. The passage of time has enriched its meanings—making it into a kind of universal patrimony—even as the era of Muslim rule recedes into the distance. This process of memorialization began while Arabs still ruled much of the peninsula. For poets, the caliphal seat of Córdoba, sacked in the early eleventh century, became a site for melancholy reflections on past glories and the inscrutable workings of destiny. “O people of al-Andalus,” exclaims the eleventh-century Valencian Ibn Khafaja, in lines that have been quoted many times since, “How God showered you/with water, shade, rivers, and trees!/The Garden of Paradise is nowhere if not in your land.”

Al-Andalus has also fascinated modern Arab writers, for slightly different reasons. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many nationalists began looking to the past, especially the precolonial past, for examples of Arab achievement and power. Muslim Spain provided an obvious model: a lost homeland (in Arabic, al-watan) that might console and inspire in the face of foreign rule. In this view, Ferdinand and Isabella’s Reconquista was the early harbinger of a long history of occupation and exile.

The Egyptian Ahmad Shawqi, known as the “the prince of poets,” was expelled to Spain in 1914. In Cairo he had served as court poet to the khedive Abbas II, deposed by the British at the outbreak of World War I for his Ottoman sympathies. Shawqi spent the next six years in Spain, where vestiges of Arab al-Andalus reminded him vividly of home. In his famous “Poem Rhyming on the Letter Sin,” Shawqi wandered among the ruins of Córdoba, seeing everything through the fractured lens of exile: the magnificent Andalusian past, the empty palaces and mosques of the present, the heartrendingly absent Egyptian watan. In the poem’s final lines, he promised that his children “would take these ruins as sermons,” for “if you cannot turn toward the past, you will never find consolation.” For Shawqi, as for many Arab thinkers, al-Andalus is a site of memory and desire, evoking nostalgia for a long-vanished history that nevertheless seems to offer important lessons for the present.

Advertisement

Eric Calderwood’s On Earth or in Poems is, he writes, a study of the “cultural afterlife” of Muslim rule in Spain. He is especially interested in its afterlife among modern Arab intellectuals. Almost every political and cultural movement in the Arab world has engaged with al-Andalus in some fashion, and Calderwood’s book is a tangle of case studies: Arabists, the Berber identity movement, feminists, Palestinians, contemporary musicians. (He doesn’t explain why he chose these groups and not, for example, Islamists or Arab secularists, who have their own views on the subject.) Through their poems and pamphlets, films and songs, each group produced what Calderwood calls a “myth” of al-Andalus. He’s less interested in the accuracy of these myths than in their political uses. As he puts it, “Modern-day claims about al-Andalus are often as much (or more) about addressing the needs of the present as they are about understanding the past.”

For historians, the history of al-Andalus begins in 711, when Umayyad armies commanded by Tariq ibn Ziyad conquered most of Iberia from the Visigothic kings. (Ibn Ziyad is the namesake of Gibraltar, from the Arabic Jabal Tariq, “Tariq’s mountain.”) Some forty-five years later, ‘Abd al-Rahman established his new capital in Córdoba. It soon became a center of civilization to rival Baghdad, with innumerable libraries, opulent palaces and mosques, extensive aqueducts, hundreds of public baths, and markets with goods from India, China, and Northern Europe, all defended by one of the most powerful navies in the world. Jews, Christians, and Muslims contributed to making Córdoba “the homeland of wisdom,” as a later Arab encomiast called it, “the home of right reasoning, the garden of the fruits of ideas.”

Umayyad rule lasted until the early eleventh century, when warring army factions splintered the caliphate into independent city-states. The era of so-called petty kingdoms was a moment of political discord but cultural flourishing, most conspicuously in the works of Ibn Hazm, author of the elegant love treatise The Ring of the Dove (1022), as well as the Hebrew verse of Shmu’el HaNagid, the Jewish vizier of Granada. The peninsula was essentially reunified in 1086 under the banners of the Almoravids, a Berber dynasty from North Africa, followed in turn by the Almohads, who also had their capital in Marrakech. The Almohads were the patrons and then persecutors of Ibn Rushd and have often been portrayed—like the earlier Almoravids—as fanatics, in part because they banned the philosopher’s works and ordered them burned in public. By the middle of the thirteenth century, the Reconquista had reduced Muslim rule to the rump state of Granada, which succumbed to the armies of Aragon and Castile in the fateful year of 1492.

Modern thinkers have pulled at separate though often overlapping strands of this dense historical weave. Arab nationalists focused on the perils of factionalism and the strength that comes through unity. For secular liberals, the Andalusian experiment proved the benefits of cultural openness, unfettered inquiry, and religious tolerance. For many Palestinians—as for many Jews—it was a cautionary tale about the loss of homeland and the sorrows of exile. Calderwood compares these collective memories to a Swiss Army knife, “a varied kit of tools ready to address all sorts of problems and needs.” He looks askance at the search for “an ontology of al-Andalus”—in layman’s terms, a study of what it was—and calls instead for a “phenomenology,” which would show instead “how al-Andalus has manifested in diverse times and places.”

The most popular tool in this interpretive kit, which a host of thinkers have used to understand al-Andalus, is the concept of convivencia, or coexistence. Many English-language readers encountered this idea in the scholar María Rosa Menocal’s The Ornament of the World (2002), a lyrical portrait of what she calls medieval Spain’s “culture of tolerance.” In Menocal’s frankly idealizing—and widely read—account, which draws largely on literary and philosophical sources, Andalusian Muslims, Jews, and Christians created a society of “eclectic syncretism,” tragically undone by religious puritans: first the Almoravids and Almohads, then the armies of Ferdinand and Isabella. Menocal finished her book just before the September 11 attacks, and her excavation of “the unknown depths of cultural tolerance and symbiosis in our heritage” was especially timely at a moment when headlines warned of a looming clash of civilizations.

The idea of convivencia, though often associated with Andalusia, is not Andalusian: its roots lie in the much more recent past. The word was first used in the peculiar—and conveniently vague—sense of religious and ethnic coexistence by the Spanish historian and literary critic Américo Castro in his book España en su historia (1948). Borrowing the term from philology, where it denoted the struggle for supremacy among vernacular variants of a word, Castro gave it an existentialist turn, using it to characterize the daily interaction between Christian, Muslim, and Jewish “castes,” which he took to be the basis of Spanish identity. Castro’s argument provoked vehement responses from historians for whom the Catholic and Castilian elements of Spanish identity were paramount, and in time the debate over convivencia was assimilated into a Franco-era version of the culture wars, pitting Catholic nationalists against Republican liberals.

Advertisement

Castro’s notion of religious coexistence dovetailed with the claims of an important school of nineteenth-century Jewish thought. Heinrich Graetz, a founder of modern Jewish historiography, turned Enlightenment ideals of toleration against European Christians, contrasting the “fanatical oppression of Christianity” with the situation of Jews in Muslim cultures, where “the sons of Judah were free to raise their heads, and did not need to look out with fear and humiliation.” Though they didn’t use the term convivencia, Graetz and his colleagues were if anything more full-throated in their praise of a Jewish golden age under Muslim rule. In an ironic twist, the tendency of modern Arab historians has been to emphasize this tradition of Islamic toleration—with the implication that only Zionism is to blame for the region’s woes—while many Israeli historians have worked to disprove the notion of harmonious coexistence in Andalusia.

In an earlier book, Colonial al-Andalus (2018), Calderwood relates another set of ironies in the modern history of convivencia. Early in the twentieth century a group of Spanish intellectuals, including the writer and politician Blas Infante, agitated for Andalusian political autonomy. Opposed to the exclusivity of Spanish Falangism (as well as Catalan nationalism), Infante described Andalusian society as a racial and cultural mixture whose vitality stemmed from miscegenation. “The Arab invasion nourished Andalusians, principally with Arab and Berber blood,” Infante wrote in a passage of Ideal Andaluz (1915), turning the Spanish obsession with limpieza de sangre, or purity of blood, on its head. “The Semitic ancestry that is thrown in our face as a stigma…is our greatest claim to glory.” In contrast to Spanish intellectuals who looked north for the wellsprings of civilization, Infante characterized Europe as a barbarous colonizer. He called Andalusians “Euro-Africans, Euro-Orientals, universalist men.”

Infante was murdered by fascists at the start of Spain’s civil war, but Calderwood carefully traces the surprising survival of his ideas in Francoist ideology. Infante’s turn toward Africa was born of the conviction that Spain and Morocco belonged to a single historical region—Andalusia—that ought to be reunited. In 1931 he asked that the Spanish Protectorate in northern Morocco, a slice of coastal territory governed by Spain since 1912, be ceded to Andalusian authority. This idea of Spanish–Moroccan unity became a cornerstone of Franco’s own colonial policy, which justified Spanish rule of northern Morocco on the basis of a common Andalusian past. Franco used this myth to help recruit 80,000 Moroccan soldiers to his side of the civil war, while also supporting the Moroccan nationalist movement in its struggle for independence and even organizing a steamship to carry Muslim pilgrims from Morocco to Saudi Arabia.

In a final irony, convivencia has become part of official Moroccan identity. The country’s constitution declares the importance of its Andalusian past and affirms “the Moroccan people’s attachment to the values of openness, moderation, tolerance, and dialogue.” Although Morocco gained independence in an era of anticolonial insurgency, the twists and turns of convivencia show how, in Calderwood’s phrase, “a Spanish way of talking about Morocco became a Moroccan way of talking about Morocco.”

Some of these ironies are perhaps more muted than Calderwood suggests. Spanish and Moroccan nationalists had a common enemy in France, and their alliance was determined by political interests—and possibly a shared antipathy to atheism, another theme of Franco’s propaganda—more than any shared commitment to Andalusia. Moroccan nationalism emphasizes precisely those moments of the medieval past—the Berber regimes of the Almoravids and Almohads—that Spanish writers including Infante have typically disdained. Pursuing the vagaries of Andalusia’s afterlife in political rhetoric, one eventually wonders whether this is truly a history of ironic reversals or merely cynical manipulations. What if Andalusia isn’t so much a tool kit as an empty vessel? What if it can mean anything we want it to?

In his new book, Calderwood worries over this possibility. He acknowledges that Berber intellectuals, feminists, and Palestinian poets took very different lessons from the ruins of al-Andalus. But he argues that “extreme plasticity” is part of Andalusia’s power, its ability “to mold and adapt to different places and times.” His scholarly aim is “to tolerate contradiction”: “Al-Andalus means many different things to many different people, and the ethical challenge is to keep all of these disparate meanings in mind without having one dominate the others.” Open-mindedness might be the best option once questions of historical truth—that is, the “ontology of al-Andalus”—have been set aside. But Calderwood doesn’t actually think that all interpretations of al-Andalus are equally good.

His first chapter is a critique of what he calls “Arab al-Andalus,” “the most enduring and resilient of the competing visions of al-Andalus” in the book. This isn’t the collective memory of a discrete political tendency but the myth propagated by mainstream Arab culture as a whole. Calderwood finds examples of this tradition in a trilogy of early-twentieth-century historical novels about Andalusia by the Lebanese writer Jurji Zaydan, which he compares to a popular Syrian television series on the same subject, produced in the early Aughts. Calderwood argues that the Arabist version of al-Andalus is exclusivist in racial terms—the heroes of the histories are Arabs, while the villains are often Berbers—as well as geographic ones: at the origin of Andalusian history is Umayyad Damascus, not Almoravid Marrakech.

This is the only instance of critique in a book that otherwise celebrates Andalusia’s infinite adaptability. But the terms of Calderwood’s argument are remarkably vague. In what sense are these two works, however popular, representative of “Arab” collective memory? The cultural Arabism of Zaydan is historically and ideologically distinct from the Syrian Baathism that seems to inform the television show, but Calderwood says nothing about Arabism or Baathism or their relations. He writes that historical claims about al-Andalus are addressed to “the needs of the present,” but does not specify which current needs and actors—the Levantine elite? the Syrian regime?—are served by these Arabist narratives.

Calderwood wants to challenge the convention of linking Andalusia with convivencia; coexistence wasn’t the only way modern Arabs thought about the legacy of Muslim rule. Yet the liberal principles of tolerance and inclusion are Calderwood’s own political yardsticks. It is the exclusionary nature of the “Arab” myth—its denial of Berber contributions to Andalusian history—that he objects to. Blas Infante imagined a republic of endlessly hyphenated identities: Euro-Orientals, Euro-Africans, and others. His slogan was: “In Andalusia, there are no foreigners.” Tolerance for all is a very high bar, however. In his first book, Calderwood shows how Infante’s own andalucismo fell short. In the last chapter of his new book, he wonders whether a group of contemporary musicians might meet the standard.

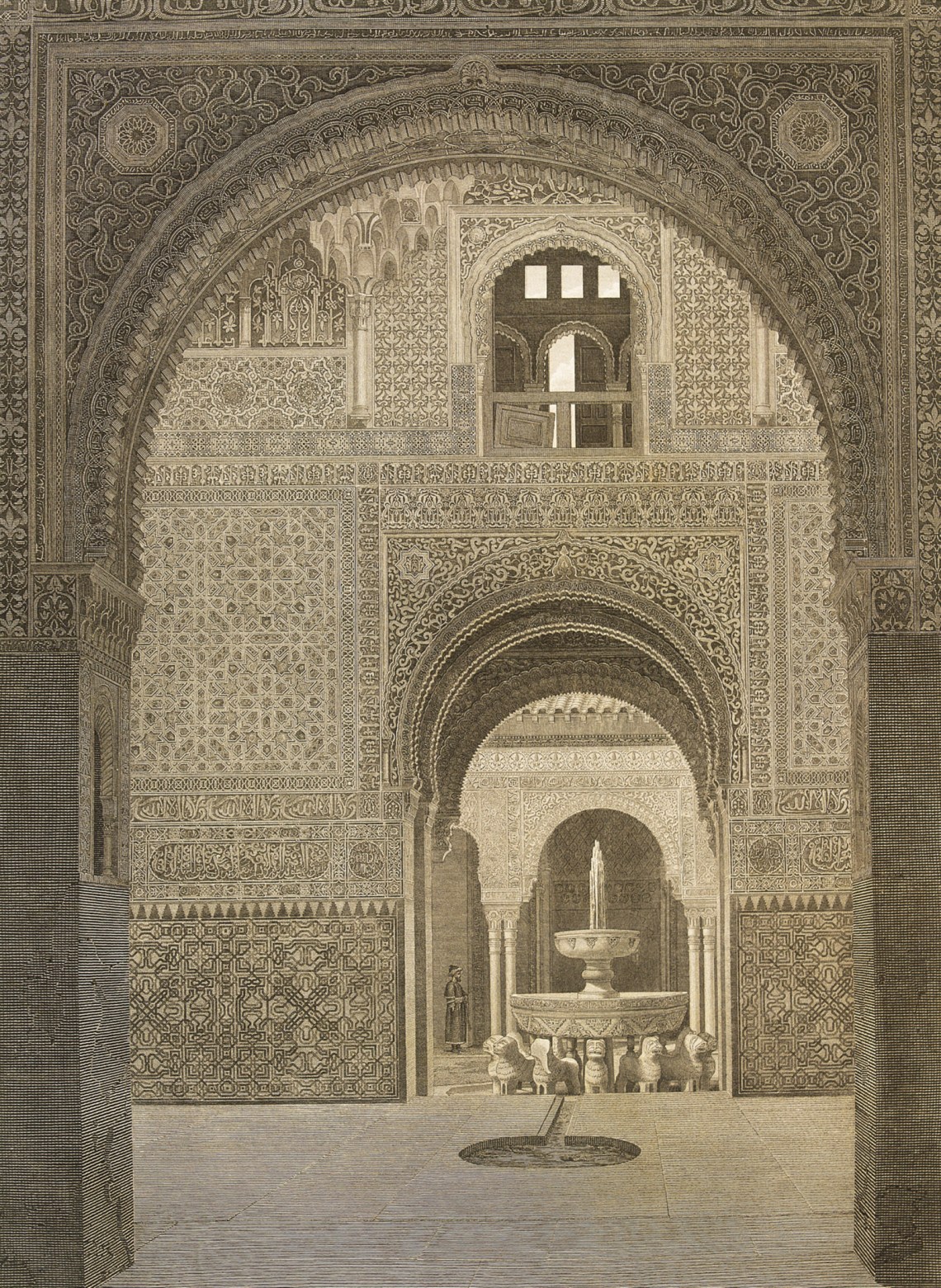

The chapter initially seems out of place. It is the only one that doesn’t explicitly concern a political group. But in fact Calderwood’s musicians are best understood as modern liberals. Reprising elements of his work on andalucismo, he shows how Spanish and Moroccan artists have collaborated to invent a hybrid musical tradition that claims medieval roots. This is the tradition of Federico García Lorca’s reflections on the cante jondo, as well as Infante’s writing on flamenco music. “Can ideas that once served colonialism be rehabilitated today in the service of productive intercultural dialogue?” Calderwood asks, and his answer seems to be yes. The musicians’ commitment to exchange, harmony, and fusion makes them exemplary of a new convivencia. His argument culminates in an “intersectional analysis” of songs by Khaled, a Spanish rapper of Moroccan descent who sings in several languages and fuses flamenco with trap. “¡Al-Andalus es mi raza!” Khaled affirms in one track—“Al-Andalus is my race!”—signaling his solidarity with the downtrodden on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar. In the music video for “Volando Recto” (Flying Straight), Granada’s Alhambra makes an appearance.

Gangsta rap, a genre of turf wars and swaggering self-praise, is a funny place to look for convivencia. In a line from “Volando Recto” that Calderwood doesn’t quote, Khaled taunts his rivals: “I’m gonna fuck you in the ass and I’m no faggot.” On another track, “La Bendición,” celebrating the mean streets he comes from, Khaled sings, “Gypsy, Latino, Maghrebi—no one’s a Christian here.” The connotations of “Christian” (Khaled uses the Arabic nasrani) might be debated, but the sentiment isn’t exactly intersectional. This isn’t a criticism of Khaled’s artistry, obviously, but it is hard to see why the rapper’s version of al-Andalus, with its various inclusions and exclusions, is more palatable than the “Arab” version Calderwood criticizes. The liberal principle of tolerance for all, as with Infante’s original formulation, seems fuzzily utopian and inconsistently applied.

The greatest meditation on al-Andalus by a modern Arab thinker is the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s lyrical suite “Eleven Planets at the End of the Andalusian Scene.” Calderwood, who takes the title of his book from a line in the poem, rightly calls it “the zenith” of Palestinian writing on al-Andalus. Darwish’s title refers to the Quranic story of Joseph, one of the poet’s favorites, who tells his father of a dream vision in which he sees the eleven planets, along with the sun and the moon, bowing down before him. In Darwish’s poem, which comes in eleven parts, Joseph’s vision of future glory is transformed into a set of oracles from the past. A chorus of speakers from the final days of Arab al-Andalus parade through the text, singing of the cycles of history and tallying up their losses.

Darwish published his poem in 1992, a year after Palestinians and Israelis convened in Madrid to begin the negotiations that culminated in the Oslo Accords. The Israeli prime minister, Yitzhak Shamir, opened his remarks to the conference by recalling the five-hundredth anniversary of the Jewish expulsion, and he quoted the Jewish-Spanish poet Yehuda Halevi on the yearning for Zion: “My heart is in the East, while I am in the uttermost West.” Darwish was suspicious of those nostalgias, as well as the negotiations. In a poem on the Palestinian exodus from Beirut in 1982, he wrote of the Arab regimes’ lip service to the Palestinian cause, “Atop every minaret/there’s a snake charmer and a rapist/preaching al-Andalus.” In the Madrid peace talks, Darwish saw history repeating itself. The Arabs were being expelled again and their leaders were signing the terms of capitulation.

But Darwish’s poem is the opposite of bitter or hectoring. Its power lies in its disquieting aloofness, as if the poem’s vision of historical gyres, of “conquest and counterconquest,” granted its speakers an almost inhuman equanimity. A cataclysm is coming, but in the opening section of the poem, voiced by a collective—possibly the soon-to-be-expelled inhabitants of Granada—the mood is spookily calm:

On the last evening on this earth, we sever our days

from our trees, and count the ribs we will carry along

and the ribs we will leave behind, right here…on the last evening

we bid nothing farewell, we don’t find the time to end who we are…

everything remains the same…

our tea is hot and green so drink it, our pistachio fresh so eat it,

and our beds are cedar green, so surrender to sleepiness

after this long siege, sleep on our dreams’ feathers,

the sheets are ready, the perfume by the door is ready…

(translated by Fady Joudah)

Perhaps the logical extreme of convivencia is to welcome the enemy into one’s home. But to hear only an exhausted fatalism in Darwish’s poem is to miss the stubbornness of “we bid nothing farewell,” or “everything remains the same.” Conquerors come and go, we might say, but the conquered leave their traces too. In that sense, they never really leave. As Edward Said wrote about “Eleven Planets” and its uncannily posthumous tone, the poem isn’t so much about the time of ending “but what happens after the ending, what it is like to live past one’s time and place.”

Darwish often expressed his ambition to become a “Trojan” poet. History may be written by the winners, but as Darwish told one interviewer, “there’s more inspiration and human richness in defeat than in victory. There is great poetry in the experience of loss.” Calderwood writes that “Eleven Planets” is not a poem that weeps over a vanished homeland, but one that looks to possible futures—Andalusian as well as Palestinian. This is how Darwish himself tended to talk about “Eleven Planets.” But that reading skips past what is most unsettling about the poem, which is its determination to view things solely from the perspective of defeat, as if history were an accumulating series of expulsions. For Darwish, adopting this point of view—while maintaining a sense of composure and dignity—allowed him to stand with other vanquished peoples and exiles, from the inhabitants of Troy to the Arabs of Granada to the Palestinians of 1948. Consolation, if there is any to be found in this grim vision, comes from the poetic universals of loss, not the passing particulars of victory.