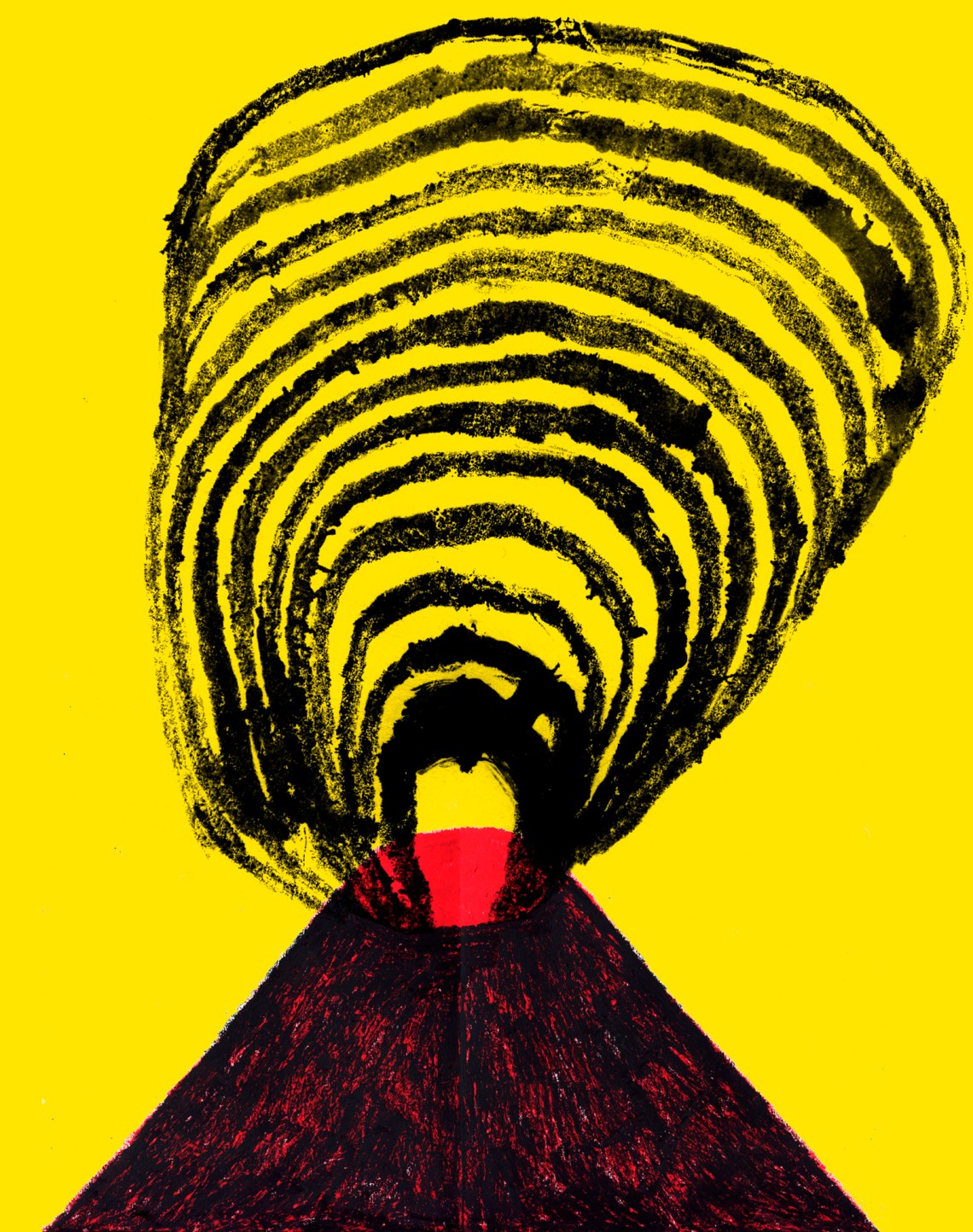

Is there anything as terrifyingly majestic as an erupting volcano? The ground shakes, fountains of incandescent lava spurt skyward, and roiling clouds, alive with lightning, grow with alarming speed. Volcanoes are so much larger than anything human, and they care nothing for us, as revealed by the body casts of Pompeii and Herculaneum, in which the death agonies of some of their victims are frozen forever.

In Mountains of Fire, Clive Oppenheimer, a professor of volcanology at the University of Cambridge, recounts a life spent studying volcanoes up close. He is an extraordinary individual who somehow finds serenity in the chaos at a volcano’s crater and admits to feelings of loss when he must descend back toward civilization. Many of the volcanoes studied by Oppenheimer lie in the remotest reaches of our planet: he is one of the few foreigners ever to be allowed access to North Korea’s sacred Mount Paektu, and he has traversed the war-torn and hostile Danakil Depression, near the border between Ethiopia and Eritrea, with its myriad vents and calderas; Oppenheimer has also ascended Antarctica’s Mount Erebus a dozen times. His book is a tale of gripping adventure, undertaken in the constant shadow of death by volcanic mishap, appalling weather, lawlessness, or warfare.

Oppenheimer’s specialty is the analysis of volcanic gases. When he began his career in the 1990s, the instruments he used were so rudimentary that it was necessary to get very close to volcanic vents to take observations. He recalls having to work within fifty meters of craters on Stromboli, off Sicily’s northern coast, as bombs of molten lava pelted the ground around him and asphyxiating gases shot from nearby crevices. The area is considered so dangerous that today nobody is allowed anywhere near it. Perhaps in an attempt to deter others from the rash ways of his youth, he writes, “It’s an understatement to say that this fieldwork was imprudent.” His measurements, gained at such risk, sadly proved to be of little value.

Mountains of Fire is far more than Oppenheimer’s tale of heroic scientific exploration, for it weaves his personal accounts with a splendid history of volcanology. Before scientific volcanology arose, these fearsome structures were explained by the imagination. In his 1665 book Mundus Subterraneus, the German scholar Athanasius Kircher alleges that the oceans enter the earth’s crust in a giant whirlpool off the coast of Norway, mingle with fire to fuel volcanoes, then exit through a great fundament near the South Pole. In more recent times scientists have established that volcanoes erupt when molten rock (or magma) that has pooled in an underground chamber reaches the surface, releasing lava (as magma is called after it breaches) and gases. Sometimes volcanic vents become blocked; if water enters the magma chamber, the pressure from the resulting buildup of steam leads to explosive eruptions.

This Issue

March 7, 2024

Circuit Breakers

‘She Talk Her Mind’