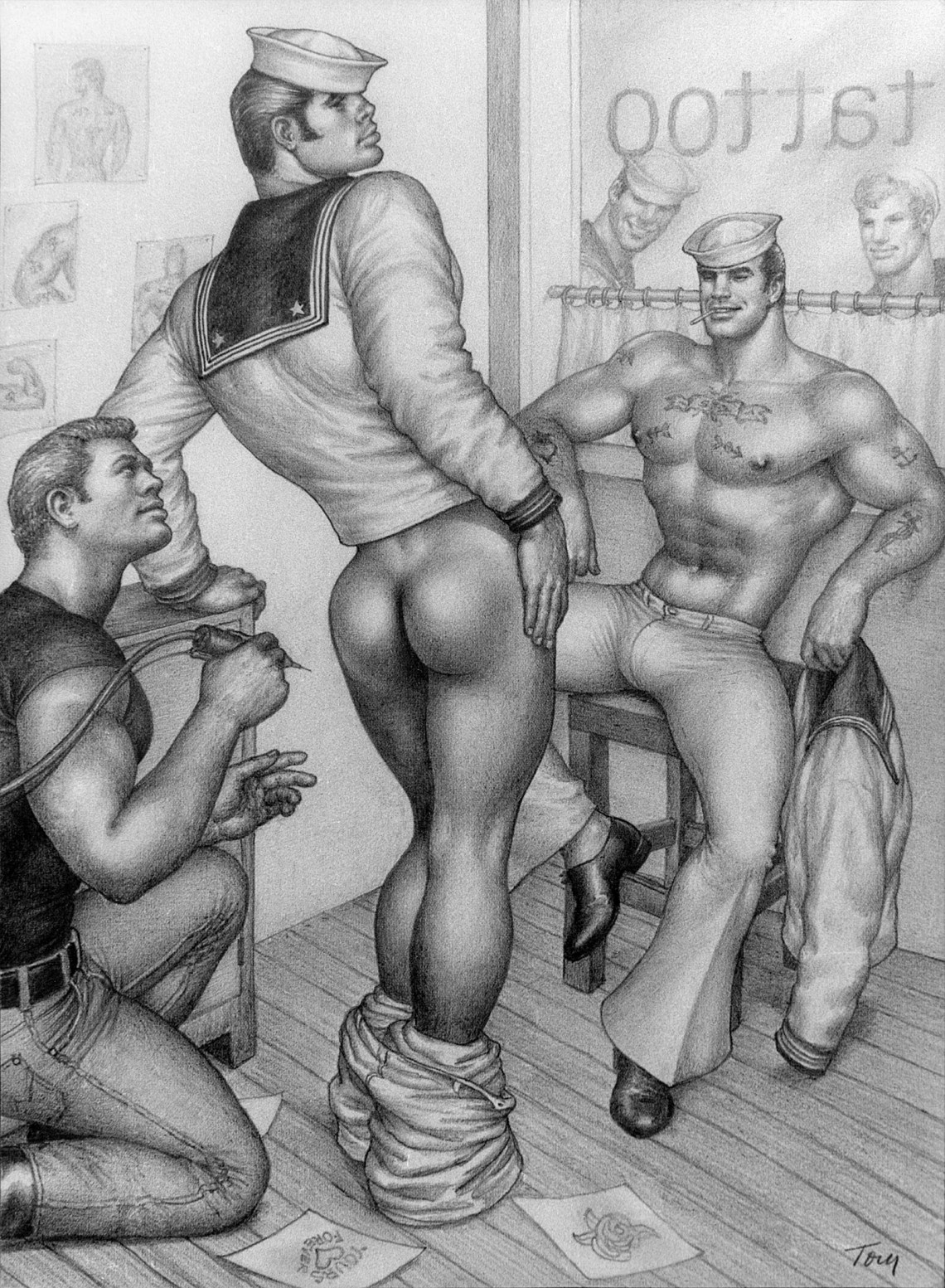

His pants are pulled down over his feet like a ruched satin shade. His hips are slung to one side in classic contrapposto, showing off the bounciest bubble butt you ever saw. His tiny waist is just glimpsed beneath the bottom of a sailor’s white shirt, which covers an improbably broad back that curves in a long “S” from neck to pelvis. His head, perched in profile as he looks over his right shoulder, has features of exaggerated, cartoonish masculinity: short straight nose, full pouting lips, strong jaw, pronounced chin, angular sideburns. His cap slides down over his forehead with an attitude of arrogant nonchalance as he revels in the pleasures of being beautiful and being seen. It’s so hypermasculine that it bends toward high femme, the pose and the voluptuousness recalling the Venus Callipyge—“Venus of the beautiful buttocks”—a Roman marble statue of the love goddess lifting her dress and allowing mortals to marvel at otherworldly perfection.

This he-man Venus stands at the center of a tattoo parlor, flanked by the tattooer kneeling like a worshiper, looking up, needle in hand. On his other side a sailor lounges, stripped to the waist and heavily but delicately muscled, with small symbols inked on his smooth chest and arms. He smiles, watching, cigarette dangling from his mouth. Two more sailors peer in the window above a low curtain, merrily gawking at what we, viewers of the drawing, cannot: the sailor’s dick, as proudly displayed for them as his ass is to us. The scenario is a machine for desire that acknowledges and incorporates our position as voyeurs mirroring those two out on the street looking in. We are welcomed into a homosocial and homosexual world where the glories of what we can see spur us to imagine what we cannot: the play between the two defines eroticism in a pictorial field.

The drawing is a classic Tom of Finland from the 1960s, and it was instrumental in forging the visual lexicon of modern gay identity. Like most of his work from the period, this image appeared in Bob Mizer’s pioneering Physique Pictorial, as the back cover of the September 1967 issue, in the days when pornographers walked a tightrope of obscenity law (no fully nude images appeared in the magazine until 1969). Under the guise of “art,” these drawings could get away with far more suggestive bulges without technically violating the restrictions. Repression produces its own aesthetic.

While the original 1967 graphite drawing is twice the size of the magazine page, it only measures 12 x 8 7/8 inches. It is now owned by Jack Shear, a photographer and the executive director of the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. When I curated a selection of Shear’s collection at the Drawing Center in New York City in 2021, I included this drawing, along with another more explicit Tom of Finland piece, hung next to Vija Celmins’s immaculate Galaxy (1974), which depicts a scatter of starlight, to see how the shine of Tom of Finland’s black leather would look beside Celmins’s glittering deep space.

Shear told me that he’s loved Tom of Finland’s drawings ever since he encountered them in Physique Pictorial as a teenager in the 1960s, and he later acquired several. “When you look at the drawings themselves you see what a great draftsman and storyteller he was in the tradition of old master drawings,” Shear explained. “It’s about quality.” At the Drawing Center they appeared right at home amid visually rigorous artworks no less driven by sexual obsession by Ingres, Balthus, and Robert Gober. Which is to say, their inclusion proved less a provocation than a confirmation of Tom of Finland’s transformation from midcentury gay pornography to twenty-first-century art.

That mainstreaming happened slowly at first, beginning on the outskirts of the gay and erotic art worlds at the end of the last century and becoming increasingly visible over the last decade, from the MOCA Los Angeles exhibition “Bob Mizer and Tom of Finland” in 2013 to Tom of Finland’s inclusion in exhibitions at major museums (such as the Met’s “Camp: Notes on Fashion” in 2019 and the Centre Pompidou’s “Over the Rainbow” in 2023). The estate is now represented by the hip blue-chip David Kordansky Gallery, which recently mounted shows in Los Angeles and New York. This rise in his reputation culminated in “Tom of Finland: Bold Journey,” a major retrospective in 2023 at Kiasma, the national contemporary art museum of Finland, which embraced its native son as “one of the most recognized Finnish artists in the world.”

In a larger sense this reevaluation can be understood alongside the reemergence of figurative painting as a dominant force in contemporary art, the development of sexually explicit “queer figuration,” and the breakdown of art historical and institutional hierarchies, which have so long excluded minority artists and popular culture. It also reflects the evolving position of queerness—a catchall term for highly variegated nonnormative sexual identities—within public life and the increased visibility of sexuality in the larger culture. Hard-core pornography, blurring into the mainstream, has never been more accessible. As a culture we are warring about politics, about bodies, about gender, about sex, and flexing at those intersections stands Tom of Finland, who has never looked more like an old master.

Advertisement

The details of his career are recounted in F. Valentine Hooven III’s Tom of Finland: The Official Life and Work of a Gay Hero, a deluxe expansion of his heavily illustrated 1992 biography, which was written in collaboration with the artist and appeared a year after his death, with his quotes printed throughout in red ink, like the words of Christ in a red-letter Bible. Tom of Finland was born Touko Laaksonen in 1920 in the rural village of Kaarina, near Finland’s southwestern coast; his parents were schoolteachers. When he was a teenager, making what he called “dirty drawings” became his secret erotic life.

After the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939, the nineteen-year-old Laaksonen was called to basic training and eventually put in charge of an antiaircraft crew. He remembered being disappointed by the loose-fitting Finnish uniforms, especially when contrasted with those of the Nazi soldiers, who arrived during Finland’s military alignment with Germany against the Soviets. Laaksonen began having anonymous public sex with Wehrmacht soldiers. “The whole Nazi philosophy, the racism and all that, is hateful to me, but of course I drew them anyway,” he later said. “They had the sexiest uniforms!” Hooven gingerly notes, “Many years later, Tom’s honesty in portraying his response to the powerful imagery of Nazism got him into trouble.” What his engagement with Nazi aesthetics means for our understanding of his art and its influence on contemporary queer identity remains a tangled question.

After the war, in his mid-twenties, Laaksonen returned to school, studying music during the day at the Sibelius Academy and graphic design at night. Tall and elegant, dressed as a dandy, he worked in advertising and played piano in cocktail lounges. Despite the criminalization of homosexuality, there was a nascent gay social life in Helsinki. Laaksonen disliked its “effeminacy.” “I tried to dress and behave the way I thought I had to when I was with them. But it was no good,” he recalled. “I was young and did want to be liked—but it just felt so wrong to me that eventually I gave it up.” He retreated into a macho all-male dreamworld in his drawings, which he showed furtively to friends and men he picked up cruising; often he gave them away. The earliest extant works from this time look more like fashion plates, colorful gouaches of cheerful businessmen in oversize popped collars and tailored pants admiring one another’s erections.

Mizer, the entrepreneurial cheerleader of gay erotica, started Physique Pictorial in 1951. The magazine was a sort of mail-order catalog displaying “athletic photographs” from a variety of studios, from which additional (and more explicit) photos could be purchased discreetly by mail. The male models, all outfitted with a thong-like posing strap, were usually photographed with goofy props like a lasso or a Corinthian column, in much the same way that laurel wreaths provided classical cover for Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden’s soft-core photos of shepherd boys at the turn of the century. There were also reproductions of physique art, most prominently paintings by George Quaintance, whose baroque erotic fantasias involved Spartan warriors, Aztec priests, and ever mythical cowboys. Beefcake images from Mizer’s own photographic studio, the Athletic Model Guild, set a high standard, and his publication swiftly coalesced into a community, with how-to injunctions to “TAKE YOUR OWN PHYSIQUE PHOTOGRAPHS” and requests for amateur work:

NEW ART TALENT SOUGHT! The editors of Physique Pictorial are certain that among the thousands of artists patronizing the studios advertising in its book, a great deal of outstanding talent must exist. We should like to see photographs (which will be returned if self-addressed stamped envelope is included) of Physique paintings which you feel might be of general interest.

Laaksonen mailed in his drawings, signing them simply “Tom.” The first to appear was on the cover of the spring 1957 issue: a smiling, shirtless lumberjack, in high fisherman boots rolled down to the ankle, tight jeans, and leather belt and knife at the waist, balances on a log floating down a river hedged by a perfunctory forest, with an almost identical figure paddling a bit behind him. By the winter more appeared under the moniker “Tom of Finland.”

Soon Tom of Finland emerged as Physique Pictorial’s most popular artist. In addition to hale and hearty outdoorsmen, he developed a repertory of bikers, policemen, soldiers, and sailors, fixating on the details of their thick gauntleted gloves, leather jackets and caps, calf-high buckled boots, skin-tight ripped shirts, and bursting chaps and jeans. Over time these archetypes, with all their slight variations, were synthesized into a single ideal, dubbed “Tom’s Men.” Instantly recognizable, they were characterized by the merger of explicit and often brutal sex with wholesome delight. Even in the more elaborate S-M scenes, in which groups of leather-clad men whip, spank, and humiliate their bound submissives, there is a sense of joy telegraphed by the ecstasy of their grimaces. This was by design, he explained:

Advertisement

In those days, a gay man was made to feel nothing but shame about his feelings and his sexuality. I wanted my drawings to counteract that, to show gay men being happy and positive about who they were…. I knew—right from the start—that my men were going to be proud and happy men!

In this sense Tom of Finland’s imagery was perfectly positioned in the run-up to Stonewall and the modern gay rights movement. It refused the clichés of homosexuals as sissy inverts and paved the way for the macho Castro clones of the 1970s. Reproductions proliferated in magazines and flyers and were heavily bootlegged, passing between friends and becoming standard decor in gay bars. The scholar Andy Campbell has recently argued that it is through this printed ephemera, rather than the original drawings, that the cultural impact of his work should be measured. Tom’s Men, born of his own desires, inspired living people to model themselves after the drawings, as if to make his fantasies into reality. Half a century later, in nightclubs and back rooms around the world, there are still men whose appearance is attuned to Tom of Finland’s rigorous example.

Roland Barthes distinguishes pornography from erotic art, describing it as a form made for a singular purpose:

Like a shop window which shows only one illuminated piece of jewelry, it is completely constituted by the presentation of only one thing: sex. No secondary, untimely object ever manages to half conceal, delay, or distract….

A proof a contrario: Mapplethorpe shifts his close-ups of genitalia from the pornographic to the erotic by photographing the fabric of underwear at very close range: the photograph is no longer unary, since I am interested in the texture of the material.1

In his description of the surface of the fabric against the body in Mapplethorpe’s photograph, Barthes identifies a similar eroticism found in Tom of Finland’s drawings, less in the body itself than in the body tightly sheathed, revealed and concealed simultaneously. Tom of Finland echoes Barthes when he says:

I almost never draw a completely naked man. He has to have at least a pair of boots or something on. To me, a fully dressed man is more erotic than a naked one. A naked man is, of course, beautiful, but dress him in black leather or a uniform—ah, then he is more than beautiful, then he is sexy!

The specificity of the uniform locates the figures within a drama of authority and hierarchical power play, and over and over those positions are subverted, destabilized, and rendered fluid. A highway patrolman might pull over a biker, might forcibly restrain and gleefully sodomize him, but in the next drawing the roles have reversed. Everyone is having a good time. Several sequences follow an outfit being partially stolen and worn by someone else, a transgression that incites sexual reprisal.

As Tom of Finland’s images were cresting in popularity in the mid-1970s, Susan Sontag asked in “Fascinating Fascism”:

In the sex shops, the baths, the leather bars, the brothels, people are dragging out their gear. But why? Why has Nazi Germany, which was a sexually repressive society, become erotic? How could a regime which persecuted homosexuals become a gay turn-on?2

The essay grapples with the attempt to rehabilitate the career of the Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl and the presence of fascist-inflected imagery in the homoerotic novels of Yukio Mishima and in Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963). Sontag doesn’t mention Tom of Finland, who at the time was still considered a mere pornographer, but she does turn her attention to the eroticization of Nazi paraphernalia, especially in gay S-M scenes, and ends with characteristic style: “The color is black, the material is leather, the seduction is beauty, the justification is honesty, the aim is ecstasy, the fantasy is death.” Her observation that within the emergent gay imagination there flickers something that looks like fascism—in its turbo-charged aestheticism, in its worship of the male body, even in the camp of its fetishism—continued to haunt discussions of the leather scene, and Tom of Finland in particular, for decades.

In 1988 Nayland Blake wrote the first serious appraisal of Tom of Finland for OUT/LOOK : National Lesbian and Gay Quarterly. He begins by arguing for the serious study of pornography:

When the history of gay images and representations is written, it will contain a large section on our pornographers. In a milieu that has produced a new connoisseurship of sexual acts, what we arouse ourselves with speaks eloquently about who we are.3

After surveying the visual elements and narrative logic of Tom of Finland’s work, Blake turns to consider “Tom the Fascist.” Speaking as an older man, the artist “expresses misgivings” about the drawings that featured SS officers brandishing swastika armbands and Nazi eagle caps, which he says he’s made efforts to withdraw from circulation. He later substituted his own logo of a winged phallus for their insignia. “People saw them in a political way because they had Nazis in them. They thought I was a Nazi,” he tells Blake. “I would not do them today because I do not want people to see them that way—they are my fantasies.”

Aside from the willful naiveté that his imagery was free of ideology, the comment pushes deeper into the heart of the question Sontag raised in “Fascinating Fascism”: What, exactly, does it mean to indulge in these fantasies, for gay men in particular? There is something suspicious in whips and chains, and in muscles that proclaim health, discipline, and purity—the ideals of gym culture seemingly come right out of Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938)—especially when seen in opposition to the more “queer” (as distinct from “gay”) imagery of glamorous drag and androgynous mess, which emerged simultaneously and was epitomized by Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963), Candy Darling and Holly Woodlawn in the Warhol circle, or the singer Sylvester, of the Cockettes, in San Francisco. A decade later, having experienced both the performance art and the leather scene of late-1980s San Francisco, Blake writes:

After the experience of Nazi Germany, it is impossible to claim that its symbols are neutral. However, it is equally wrong to say that once symbols acquire a meaning, that that meaning is fixed forever. The meaning of phrases and images does shift depending on who uses them. While Tom’s drawings utilize a style of representation popular under fascism, it would be a mistake to say that even those that contain Nazi imagery are fascist in intent or effect.

Blake was part of a new generation of politicized queer artists, along with Richard Hawkins, Tony Greene, and Lyle Ashton Harris in Los Angeles, who were simultaneously attracted to Tom of Finland and thinking critically in their own artwork about that attraction. By shifting the analysis from the intentions of the artist and his particular biography to the way these images functioned in people’s lives, one can see how they were recoded with new meaning and became complex symbols of an underground community organized around desire, in which transgression was celebrated (in ways that extend the twentieth-century avant-garde’s celebration of the Marquis de Sade). In their promiscuous movement through postcards, posters, and prints, these drawings became vehicles through which different kinds of queer people, many of whom did not in any way physically resemble Tom’s Men, recognized aspects of themselves and their own sexualities and were able to locate one another. Blake’s essay, written for a radical leftist magazine, acknowledges the troubling dimensions of Tom of Finland’s work while confirming his status as foundational within the history of queer representation.

By contrast, the recent high-profile Tom of Finland exhibitions have sidestepped the question of fascist aesthetics entirely, with “Made in Germany” (Galerie Judin, Berlin 2020), “Highway Patrol, Greasy Rider, and Other Selected Works” (David Kordansky, New York 2023), and “Bold Journey” making no reference to the existence of Nazi imagery or its lingering presence in the tailored military uniforms. What we get instead is a discursive parade of “sexual liberation,” “personal freedom,” and “gay pride.” I’ve become increasingly uneasy about this uncritical exaltation of Tom of Finland—the august retrospectives; his images printed on T-shirts and swimwear or featured in collaborations with clothing designers like JW Anderson, Comme des Garçons, and Rufskin—which seems to have one ultimate message, reducible to GAY = GOOD. What if we decide that Tom of Finland actually is bad: politically suspect, deeply fucked up? Would we be in a position to think with more subtlety about the intersections of patriarchal white supremacy and the historical project of “gay liberation”? Could we more precisely chart how body fascism and political ideology reinforce or resist each other? Or, in our need for purity, must we pretend that this aesthetic did not exert appeal for those seeking new forms of sexual community—particularly people who explicitly opposed a fascist or racist project, even while seeming to appropriate fascist props?

Kobena Mercer brilliantly interrogated his own “ambivalent structures of feeling” as a Black gay man in the 1980s through his confrontation with Robert Mapplethorpe’s sexualized images of Black male nudes. In 1986 he wrote a convincing analysis of the relentless logic of Mapplethorpe’s photographs as the product of a white male imagination and the “camera codes” that literally objectify the subjects into objets d’art:

There is a subtle slippage between representer and represented, as the shiny, polished, sheen of black skin becomes consubstantial with the luxurious allure of the high-quality photographic print.4

Once Mapplethorpe became a political lighting rod, with his death from AIDS followed by the cancellation of his retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery in 1989, Mercer reconsidered. Not wanting Black critique to be put into the service of right-wing censorship, this time he located his own sexual desire within the images, toggling among the positions of artist, model, and desirous viewer, and refusing stable positions:

The difficult and troublesome question raised by Mapplethorpe’s black male nudes—do they reinforce or undermine racist myths about black sexuality?—is strictly unanswerable, since his aesthetic strategy makes an unequivocal yes/no response impossible. This is because the image throws the question back to the spectator, for whom its undecidability is experienced precisely as the unsettling shock effect.5

Mercer suggests that Mapplethorpe’s photographs, seen from the perspective of urban gay male culture besieged by AIDS and the right-wing assault, might be read not only as “racist fantasies” but as a potentially “deconstructive strategy which begins to lay bare the psychic and social relations of ambivalence at play in cultural representations of race and sexuality,” depending on who is speaking, where, and to whom. Desire is impolitic, structured by our deepest social taboos; it is inherited and largely unconscious, built out of race, gender, and class in kaleidoscopic interaction. Operations of power will be eroticized, its forms fetishized, whether we admit it or not. An argument can be made for the practice of S-M itself as an extremely nuanced strategy for navigating these internalized structures so that they can be confronted, played with, undone—or at least brought into consciousness so they might be properly examined. In attending to the realities of desire, acknowledging that we can want things that are bad for us or painful or even harmful, Mercer’s essay arrives at no simple conclusion.

The invocation of Mapplethorpe’s work in both Barthes’s and Mercer’s accounts is not incidental. Mapplethorpe was deeply affected by Tom of Finland’s images, which friends remember him seeking out in the 1960s. When they met in the late 1970s, the young photographer helped arrange the artist’s first solo exhibition at a New York art gallery (rather than the back room of a bookstore or boot shop) in the 1980s. Mapplethorpe himself later acquired original drawings. With the icy perfection of his aesthetic, he was the controversial crossover who translated pornographic Tom of Finland subject matter into the highest spheres of contemporary art. It is in no small part thanks to Mapplethorpe that Tom of Finland’s drawings are recuperable as art today. The two share many things, including the similar racial content Mercer describes; once Tom of Finland began to spend time in the US, he increasingly drew pictures of Black men engaged in all kinds of interracial entanglements, many of which cross into blatant racial stereotype. While the positions flip, scenarios of masters and slaves pervade. Along with the specter of fascism, the logic of whiteness is left untouched in the recent rounds of art world publicity.

A refreshing article by the curator Alvin Li in the Kiasma catalog, “Boys Will Be Boys?,” notes the generational anachronism of these “gay” images in relation to current queer politics, which, among other things, encompasses gender-nonconforming body positivity:

When asked what they think of Tom’s oeuvre, my contemporaries’ responses are uniformly marked by a certain ambivalence. One described Tom’s images as “homonormative,” despite feeling like there’s also “some nuance there,” due to an “(over)performance of homomasculinity.” Another, a more feisty queer, completely dismisses the type of masculinity that Tom has so masterfully invented, describing it as something to be “resisted,” or better yet, ignored.

Ignoring it, however, will not make it go away. Queer artists and writers over the past half-century have grappled with these questions. The Canadian punk lesbian G.B. Jones’s series of “Tom Girls” drawings from the early 1990s recasts Tom of Finland scenes with tough femme dykes. In one, a woman is left bare-assed, spanked, and lashed to a tree, with “I am a fascist pig” written on her jeans tied around her ankles. “It was meant as both a tribute and a critique, a way of exchanging ideas,” Jones explains.6 Which is to say, Jones’s work is not a rejection of Tom of Finland imagery but an attempted rescue, a way of keeping him close, of moving forward.

Over the past sixty years Tom of Finland’s work has functioned in people’s lives as a source of arousal, identification, and socialization, and in ways that exceed, and often refute, their potentially fascist or racist implications. These images have not mobilized neo-Nazi militias but instead have coalesced extremely diverse kinds of bodies around kinky queer sex and fetish scenes, united in boundary-blurring sexual pleasure. In the Threesome catalog, Brontez Purnell describes his expectations of his residency at the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles:

I thought since it was Tom of Finland I would walk in the house and a ton of Aryan dudes were going to be fisting each other. But in actuality it was a plethora of queers, femme, masc, non-binary, black, white, old, twinks, etc., that all condensed into this singular space—a seemingly disparate group of tight-knit outsiders carrying the banner still of the queer alternative.

The queer alternative looks different today than it did in 1957 or 1977, with wider but still limited horizons, as it attempts to seek greater inclusiveness among diversely raced, classed, and gendered bodies. Queer people are, and always have been, astonishingly inventive and creative appropriators, alchemists of signification. But if, in order to function as contemporary art, Tom of Finland’s work has to become one-dimensionally correct, then the price is too high; it denies our humanity in all its complexity. If the choice is either unqualified celebration or total cancellation, we cease to think. And in that case, who cares if it’s art or not?

This Issue

May 9, 2024

‘Who Shall Describe Beauty?’

Israel: The Way Out

-

1

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (Hill and Wang, 1981), pp. 41–42. ↩

-

2

The New York Review, February 6, 1975. ↩

-

3

“Tom of Finland: An Appreciation,” OUT/LOOK, Fall 1988, p. 37. ↩

-

4

“Imaging the Black Man’s Sex” (1986), reprinted in Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies (Routledge, 1994), p. 184. ↩

-

5

“Skin Head Sex Thing: Racial Difference and the Homoerotic Imaginary” (1989), reprinted in Welcome to the Jungle, p. 192. ↩

-

6

Alex Denney, “The Artist Who Recreated Tom of Finland’s Drawings for Women,” anothermanmag.com, October 11, 2017. ↩