The arrivals lounge at Harare International Airport in Zimbabwe once provided a sinister foretaste of life under the Robert Mugabe dictatorship. In every corner lurked agents of Mugabe’s Central Intelligence Organization, his domestic spying agency, on the lookout for Western journalists, human rights workers, democracy activists, and other perceived enemies of the regime. It was here that Tendai Biti, the outspoken secretary-general of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), the country’s main opposition party, was arrested by security agents in June 2008 upon his return from a trip to South Africa and charged with treason, which carries a death sentence. (After international protests, he was released on bail two weeks later.)

Correspondents trying to slip into the country on tourist visas could expect to find themselves interrogated here by CIO operatives; then they would either be detained or put back on planes for Johannesburg. Most elected to enter the country through the backwater airport of Bulawayo, an opposition stronghold, or overland from Victoria Falls. “If you come through Harare,” one Zimbabwean colleague told me last year, “chances are good you’ll be sent back—or go to jail.”

Thus I was pleasantly surprised when I arrived in Harare on a South African Airways flight from Johannesburg in late August, six months after Mugabe had been forced to cede partial power to Morgan Tsvangirai, the MDC leader. The CIO seemed to have disappeared: the atmosphere was as laid back as that of a small-town airport in the United States. A friendly immigration official issued me a tourist visa on the spot for the usual $30, no questions asked, then winked as I gathered my documents and headed toward baggage claim. “Welcome to the new Zimbabwe,” he told me.

Last year at this time Zimbabwe looked very different. In March 2008, Morgan Tsvangirai defeated the deeply unpopular Mugabe by a majority vote in the presidential election, promising —it seemed—an end to a brutal, twenty-eight-year dictatorship that had brought the country economic ruin and international isolation. Mugabe refused to recognize the result and forced Tsvangirai into a runoff, then unleashed his security forces and pro-government militias on a campaign of torture and murder. At least seventy MDC activists were killed, several hundred disappeared, and 25,000 people fled their homes. Then South African president Thabo Mbeki and other regional leaders stood by, refusing to intervene or even to condemn Mugabe’s tactics. Tsvangirai withdrew from the runoff on June 22, 2008, calling it a “violent sham.” Five days later, Mugabe, running unopposed, declared himself the winner.

Mugabe’s victory, however, was not absolute. The continued implosion of Zimbabwe’s currency, combined with a spreading cholera epidemic, global revulsion at the ruling party’s violence, and growing impatience from the Southern African Development Community (SADC)—the regional group of nations led at the time by Mbeki—forced the dictator to enter talks with the opposition leaders last fall. After tortuous negotiations and several walkouts by the MDC, the two sides in September signed the Global Political Agreement, preparing the way for a “unity government”: Tsvangirai became Zimbabwe’s prime minister; Mugabe retained the presidency. The MDC received sixteen of thirty-one ministries—including the Ministry of Finance, giving the party some power over the country’s wrecked economy.

In the months since then, top officials in Mugabe’s ZANU-PF (Zimbabwe African National Union–Popular Front), who once enjoyed absolute power, have been forced into awkward proximity with their former enemies—talking with them at cabinet meetings, having meals with them, even sharing suites in cabinet retreats in the Zim-babwean bush. Still, as Human Rights Watch recently reported, Mugabe retains much control, even if ministries are officially under the authority of the MDC.

MDC officials, including Tsvangirai, argue that such grudging and partial cooperation is evidence that Zimbabwe is slowly building democratic institutions, establishing the rule of law, and laying the groundwork for a new constitution and free and fair elections next time around. “I see it as a process, and I believe the process is on track,” I was told by David Coltart, a constitutional lawyer, MDC member of Zimbabwe’s Senate, and the newly appointed minister of education. Coltart has reopened thousands of schools that had been abandoned during the Mugabe dictatorship because their teachers went unpaid. Coltart concedes, however, that the current $155 monthly teacher’s salary is barely enough for basic essentials, and members of the Zimbabwe Teachers Association, the largest of three unions, went on strike in early September to protest living in “abject poverty and perpetual debt.”

Nor does everybody share Coltart’s optimism. In a huge series of concessions by the MDC that many within Tsvangirai’s own circle opposed, the ZANU-PF still has control over the army, the police, the courts, the jails, and the Ministry of Information, which regulates the press. Thus Mugabe’s henchmen have kept their hands on levers of coercive power, including the ability to harass and detain their enemies. “Mugabe was beaten in an election, he came back through violence, and…I think he is having the last laugh,” I was told by Farai Maguwu, a human rights activist in Mutare, in eastern Zimbabwe. Indeed, there is ample evidence that the MDC has been outmaneuvered by Mugabe and his cronies, and that the former dictator, rather than being diminished, has walked away from the deal with his power and his privileges largely intact, and his legitimacy—to some degree—restored.

Advertisement

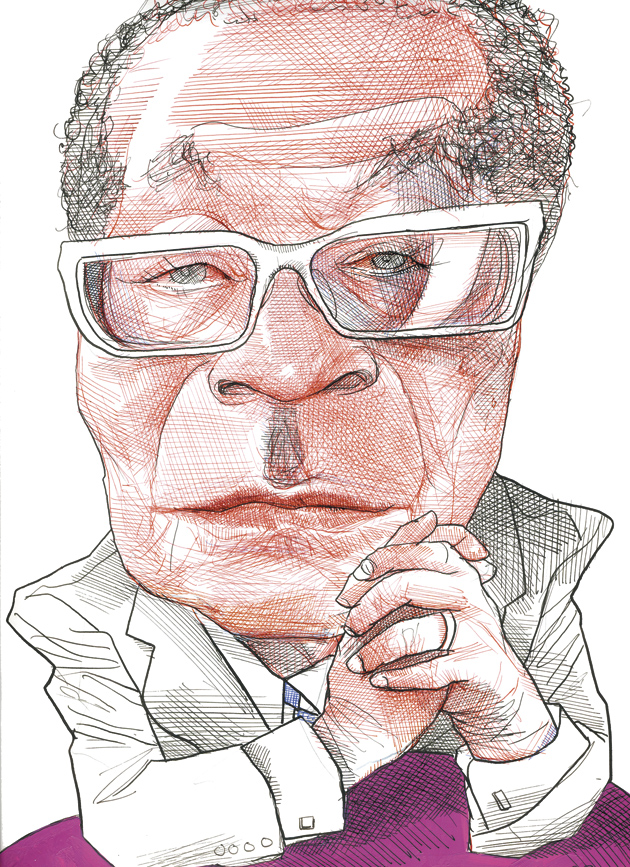

Tendai Biti, the MDC leader and new finance minister, exemplifies the cautious optimism—or, critics would say, naiveté—of the MDC today. Biti works out of a corner office on the fifth floor of a dilapidated high-rise on Samora Machel Avenue, the main thoroughfare in Harare. A tall, burly figure with a booming voice, Biti was once one of Mugabe’s fiercest opponents; he called Zimbabwe under the dictator “a predator state characterized by tolerance for violence.” Last fall, Biti urged his MDC colleagues not to enter into a power-sharing deal, arguing that Tsvangirai, as the clear winner of the March 2008 election, should form a new government without Mugabe. He was ignored. “I cried when the national council of the MDC took the decision to participate [in the unity government],” he told me. “I wanted to resign. And Morgan spoke to me, and I decided to stay.” Since then, Biti has become a supporter of the alliance.

Biti has rolled back some of Mugabe’s most pernicious economic policies. His biggest target has been the national reserve bank, run by Gideon Gono, a Mugabe protégé. During his heyday, according to human rights workers, journalists, and MDC politicians, Gono ran the bank as a personal slush fund. He printed up trillions of Zimbabwean dollars, which he used to pay the security forces, purchase agricultural equipment for rural communities to bolster support for the ZANU-PF, distribute loans to party insiders, allegedly buy diamonds in newly discovered fields in southeast Zimbabwe (which he then smuggled out of the country for hefty personal enrichment), and trade for hard currency at official government rates, which diverged wildly from black market rates. Gono’s money policy fueled a hyperinflationary spiral: in March 2008, the Zimbabwean dollar was valued at 25 million to the US dollar; two months later, it had fallen to one billion to the dollar. Factories stopped producing goods. Long lines of people stretched around city blocks in front of ATM machines, waiting hours to withdraw the equivalent of US $3—the maximum allowed by law.

In April, Biti abolished the Zimbabwean dollar and made the US dollar legal tender. (The US dollar was already widely used in Zimbabwe, though unofficially.) The move brought the inflation rate to near zero, revived the stock market, put goods back on supermarket shelves and gasoline in the pumps, and allowed commercial enterprises to establish budgets and return to business. Last spring ministries began to pay their employees in US dollars, which has drawn thousands of teachers, doctors, and other civil servants back to work—though many on the new government salaries are still scraping by.

Biti couldn’t help the millions of Zimbabwean citizens whose pension funds and savings accounts had been wiped out by hyperinflation. One sixty-year-old Zimbabwean colleague told me that he had recently cashed out his 75-trillion-Zimbwabwean-dollar pension fund—and received three US cents. And the shortage of US bills in circulation has forced some people in rural areas to barter for goods—paying in grams of gold, crops, or even animals. (The Associated Press carried a story about a woman in a rural area who boarded a bus to Harare and offered the driver a trussed, live chicken in lieu of bus fare.) But overall, he argues, dollarization has restored a measure of normality to Zimbabwean society.

Other Zimbabweans I spoke to supported this view. In Mutare, a town near the border with Mozambique, I met Ched Nyamanhindi, a young researcher for the Center for Research and Development, a human rights advocacy group. Nyamanhindi used to have to travel across the border to Mozambique two or three times a week to buy essentials like food and gas, because shops in Zimbabwe had been stripped bare. But now, he told me, “You have money, you can budget, you can plan, you can walk into a supermarket and buy food for your family. There’s no more running across the border to buy goods. Zimbabwe food products, like cooking oil, rice, sugar, salt, mealy meal, are coming back to the markets.”

Some people, however, seem determined to turn back the clock. Gono, who was appointed—and can only be fired—by Mugabe, recently announced plans to bring the Zimbabwean dollar back into circulation. Biti says it will never happen: “I don’t have the authority to get rid of him,” he told me. “But he can’t do anything without our consent.” In July, a package arrived at Biti’s home in Harare containing a nine-millimeter bullet and a message to “sort out your will.” Biti was shaken, though he vowed to continue his reforms.

Advertisement

Mugabe’s security forces continue to carry out acts of brutality. The worst such case took place in Chiadzwa, a vast field of alluvial diamonds that was discovered in 2006. Immediately after the discovery, diamond panners from across Zimbabwe—and other parts of Africa—descended on the area, some of them becoming rich overnight. Following the 2008 elections, Mugabe and the generals decided to crack down. In Operation Hakudzokwi, or “you won’t come back,” two helicopter gunships and hundreds of ground troops attacked the panners and, over a two-month period, killed several hundred of them, according to human rights groups, then cordoned off the fields with military checkpoints. “They shot the miners and left their bodies to rot in the field for days,” the human rights activist Farai Maguwu said, as we stood in front of what he said was a mass grave at a Mutare cemetery. It contained the bodies, Maguwu told me, of eighty poor diamond panners, shot down by an army brigade last November.

Today, the troops augment their paltry incomes by smuggling the diamonds across the border to Mozambique and selling them to Lebanese buyers. The MDC has demanded that Mugabe withdraw the army and turn the fields over to a reputable mining company, in order to bring transparency to the hunt for diamonds. But nothing has yet happened, and the smuggling goes on. Biti admitted that the fields—under the authority of the army and the ZANU-PF-controlled Ministry of Mines—were beyond the reach of his authority and that the government is now losing any profit from the diamonds. “We are getting zero,” he said.

In other areas as well, the MDC remains powerless. Mugabe’s police have arrested more than a dozen MDC parliamentarians—including ten seized in late August in a mass arrest during a meeting at the Ministry of Finance—on a variety of charges ranging from disturbing the peace to abducting a twelve-year-old girl. In July, the police jailed an MDC deputy minister on charges of stealing a Nokia cell phone allegedly owned by Joseph Chinotimba, leader of the Zimbabwe war veterans—who have seized thousands of white-owned farms, often at gunpoint, in a radical land-reform program initiated by Mugabe in 2000.

Meanwhile, the land reform falls under the authority of provincial governors, all of them Mugabe appointees, and of the ZANU-PF-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs. Seizures of white-owned farms continue, though by now there are only a few hundred left. (Biti told me that he wanted to stop the seizures, but that the government would not return land that had already been confiscated. “You can’t reverse the land-reform policies. You cannot have minority ownership of any resources in the country.”)

The Central Intelligence Organization—despite having been withdrawn from Harare’s airport for cosmetic reasons—is still a near-ubiquitous presence in the rest of the country. The Ministry of Information is still denying newspapers licenses, arresting journalists, and refusing to accredit others. Angus Shaw, the Associated Press bureau chief in Harare and a Zimbabwean citizen, has been working without accreditation for a decade, which can make him subject to detention at any time. Last month, he told me, he attempted to attend a press conference held by Morgan Tsvangirai—and was ordered to leave by a CIO agent lurking around the entrance. “He said, ‘if you don’t go now, your next destination will be the police station,'” said Shaw, who has been writing about the country for nearly forty years.

Such harassment and continuing lawlessness have made a mockery of the MDC’s participation in the unity government—and of Tsvangirai’s conciliatory statements toward Mugabe. (Tsvangirai recently told The Guardian that he had developed “some chemistry” with the man who had once put him on trial for treason and threatened to kill him.) “The MDC has sanitized and legitimized ZANU-PF, and they continue to do so,” said Derek Matyszak, a director of the Research and Advocacy Unit, a human rights organization in Harare. Mugabe loyalists, Matyszak says, are biding their time, “building up a war chest, and waiting for the next election.” Unless the government comes together, ratifies a new constitution, and establishes a new date for general elections, the next parliamentary and presidential vote will take place in 2013. At that point, he believes, the country could experience a new wave of violence and terror.

By 2013, there is also a good chance that Mugabe, who is eighty-five, will have faded from the scene. The succession battle continues to play out inside the ruling party, with attention focusing on two candidates, Joyce Mujuru, who is vice-president and also the wife of former armed forces commander Solomon Mujuru; and Emmerson Mnangagwa, currently the minister of defense. Both are members of Mugabe’s Shona tribe—the country’s dominant ethnic group—and both are considered to be hard-liners who stood firmly behind the campaign of intimidation and violence against MDC supporters and activists in the spring of 2008.

Neither of them, however, is believed to be a favorite of South African President Jacob Zuma, who has taken a more critical position toward Mugabe and his henchmen than his notoriously passive predecessor, Thabo Mbeki. Zuma is believed to be taking a close interest in the struggle within the ruling party to succeed Mugabe as president, though it remains unclear just how strongly he will throw his weight behind Morgan Tsvangirai. (On the other hand, Mugabe and his party, the ZANU-PF, are so widely unpopular in Zimbabwe now that Zuma would badly damage his credibility if he is seen to be meddling in internal ZANU-PF rivalries.)

This spring both Morgan Tsvangirai and Tendai Biti traveled across Western Europe and to Washington, seeking financial support for the unity government. Their efforts were largely unsuccessful. President Obama met with Tsvangirai at the White House in June and pledged $73 million to Zimbabwe, a relative pittance. He also refused to place the money directly into the hands of the government, channeling it instead through aid organizations and United Nations agencies. The funds will go to specific ministries, such as health and education, that are run by the MDC. Other Western leaders have refused to support the new government, despite cautious approval of Tsvangirai personally. In September, a European Union delegation traveled to Harare for its first talks with Mugabe in seven years, but refused to lift sanctions, citing continued lack of progress in human rights. “The default position among the donors is ‘sit back and do nothing,'” I was told in Harare by a Michigan State professor and native Zimbabwean who arrived in the country in August to conduct a research study for the World Bank. “Nobody wants to contribute funds that might end up propping up the old guard.” Western donors have established a set of benchmarks that the unity government must meet—including establishing the rule of law, respect for democracy and human rights, and commitment to free and fair elections—before the money begins flowing. A US diplomat told me that “the government hasn’t come close” to meeting them.

For their part, regional leaders, including Zuma, who pushed hard for the formation of a unity government last year, have eased off Mugabe in the last few months, glad that the sense of crisis has faded and apparently eager to return to business as usual. At a gathering of southern African heads of state in Kinshasa in early September, the leaders repeated a call for lifting sanctions against Mugabe and his cronies, citing improvements in human rights and the economy.

Biti and Tsvangirai were hoping to emerge from their trips with pledges that would allow Zimbabwe to pay off its loans from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. “I think the donors are being selfish,” Biti told me. “They are sulking. They are unhappy that Mugabe is a part of this inclusive government. They wanted proper and pure regime change. But when you are fighting a dictatorship, using nonviolent means, whatever you do is gradual.” Already, he said, “People can put on MDC T-shirts right now without violence, people can get on with their lives without any reprisals.” I asked Biti about Mugabe cronies who had benefited from ZANU-PF hegemony, and who were desperate to avoid the possibility of judgment in The Hague or some other court. “They are not powerful enough to derail this process,” he insisted. Like the Western donors, he said, “They can sulk and sulk, but we are going to do what we have to do to give our people a chance.” The trouble with such statements is that they are made under the still heavy shadow of Mugabe and his goons.

—September 23, 2009

This Issue

October 22, 2009