1.

Crime measurement, like crime-fighting, has been a shaky business for years. In the 1950s and 1960s, it was customary for municipal officials in Chicago, Philadelphia, New Orleans, and New York, among other cities, to grossly underreport their crime statistics. And the habit was hard to break; increased honesty, after all, could easily be mistaken for increased crime. It could be, and, according to Above the Law, David Burnham’s illuminating study of the US Department of Justice, eventually it was. With the advent of 911 emergency telephone systems, in the late Sixties and the Seventies, the act of reporting became easier for the public and the act of suppressing statistics harder for the police—and crime soared. While some of the growth was undoubtedly real, some, Burnham suggests, was not.

Even now, about half the victims of crime don’t bother to report it, and the police, too, retain some discretion about what gets counted, and how. In New York City, where the crime rate is said to have dropped by more than 40 percent over the last three years—“the New York Miracle,” it has been called—there have been sporadic disclosures of precinct or borough-level police commanders leaning on subordinates to downgrade robberies to larcenies or felonious to simple assaults. But suspicions of large-scale error or fraud run aground on the fact that murders and shootings, which have dropped the most (by about 50 percent each), are, of all crimes, the least manipulable. The annual tally of murders in New York City declined from 1,927, in 1993, to 986, in 1996; of shootings, from 5,862 to 2,930.

This is a miracle that can’t be dismissed. How, then, to explain it? The administration of Mayor Rudy Giuliani will brook no doubt that it’s the work of City Hall and the Police Department, with an assist from the district attorneys and the courts. But even as police leaders and consultants travel around the country preaching the new science of crime reduction to cities seeking miracles of their own, many of the people who make their livings studying these matters have felt impelled to look for another explanation, less flattering to law enforcement.

When the downward trend first began, in the early Nineties, criminologists pointed out that the number of males between fifteen and nineteen—now roughly the most crime-prone ages—had decreased by 20 percent during the previous two decades. That figure, however, soon leveled off and began slowly climbing again, yet crime continued to fall.

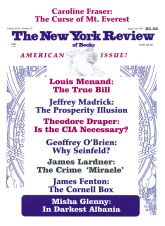

This Issue

August 14, 1997

-

1

David Burnham, Above the Law: Secret Deals, Political Fixes, and Other Misadventures of the U.S. Department of Justice (Scribner, 1996), Chapter 4, “The Numbers Game.” Burnham points out that when the Justice Department began its victimization surveys in the mid-Seventies, they showed crime holding steady, even as police/FBI crime statistics continued to suggest dramatic increases.

↩ -

2

These are New York City Police Department statistics. The shooting figures refer, more precisely, to the number of victims.

↩ -

3

Demographic statistics cited in Citizens Crime Commission, “Reducing Gun Crime in New York City: A Research and Policy Report,” pp. 42-43.

↩ -

4

See James Lardner, “Painting the Elephant,” The New Yorker, June 25, 1984.

↩ -

5

See David Remnick’s article on Maple in The New Yorker, February 24, 1997.

↩ -

6

The 1972 figure was 1.1 billion subway rides; the 1991 figure was 995 million. Last year, it was back up to 1.1 billion.

↩ -

7

Raymond Harding, interview with me.

↩ -

8

Adam Nagourney, “Poll Finds Optimism in New York, But Race and Class Affect Views,” The New York Times, March 12, 1997, p. 1.

↩