1.

Flying into LAX, you don’t bother to look for landmarks. The could-be-anywhere cluster of mirror-glass and postmodern-wallpaper towers in old downtown Los Angeles is not worth a first glance. The fine print of the Hollywood sign is often occluded by the yellowish lid of inert gases that hovers over the auto-emissions capital of the United States. The vast net of the sprawling city’s streets presents a sight of hypnotic power only when that grid is lit up in the dark.

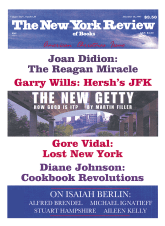

Now, however, there is something new to watch for on the L.A. horizon. You wonder whether it can be seen from the sky, and it can. The creamy, gleaming Getty Center stands out against the sere brown Santa Monica Mountains with all the impressive mass of a geological formation. In view of the kilotons of earth moved in its making and the stone used for its cladding, this architectural prodigy is indeed a man-made mountain.

As you head northwest on the San Diego Freeway from the airport to Brentwood, the Getty Center, perched high atop a distant hill, drifts in and out of sight. It brings to mind a latter-day Shangri-La—a flat-roofed, vaguely Streamline Moderne eyrie like the lamasery in the 1937 movie Lost Horizon. Just beyond the Sunset Boulevard overpass, the Getty at last heaves into full view on the steep promontory to the west of the roadway. Now you think of the Great Wall of China. The sheer cliff of buff-colored masonry looms over slopes planted with gnarled western oaks in serried ranks. Meant to signify architectural subjugation of this rugged terrain, that formal landscape effect is far too tame; it makes the Getty site look for a moment like a very fancy vineyard.

Exiting the freeway at Getty Center Drive, you switch back south on a local street, cross under the big road, and enter the Getty domain. The first order of business is for a guard to determine whether you belong there at all. Parking reservations must be made well in advance, because although there are 700 spaces for employees’ cars, there are only 850 for the general public. Unusual for L.A., the Getty has no valet parking, as the requirement to book ahead, restaurant-style, might lead one to expect. You can, however, arrive unannounced if you are willing to walk or rollerblade at least a few miles or if you come on a bike or motorcycle, take a taxi (a $10 fare from the nearest nexus of big hotels, in Beverly Hills), or ride what is known in some West Side L.A. circles as “the maids’ bus,” the public transportation line that runs along Sunset and is frequently used by the domestic help of Beverly Hills, Bel-Air, and Brentwood.

After being vetted by the Getty maître d’, you leave your car in the seven-level parking structure at the bottom of the hill, take an elevator up to the roof, and there board a small white airport-style tram that climbs three quarters of a mile up a curving, slightly raised track to the summit. Expectations run high, not only because this is one of the most complicated sequences by which a visitor arrives at any public building in America—getting into the White House is a breeze by comparison—but also because most people must plan for the experience with considerable forethought. You cannot walk into the Getty as impulsively as you might enter the National Gallery or British Museum in London, or the Frick or Metropolitan in New York. Tourists at the Getty might be reminded of the ascent to Hearst Castle, the megalomaniac publisher’s mountaintop estate several hundred miles to the northwest, though the Getty lacks free-range zebras.

But when the tram comes to a halt and you emerge at the long-awaited destination, hopes of mystery and magic fade away in the blazing sunlight. The first, punishing impression is one of blinding glare. The highly reflective surfaces of the broad entry plaza (paved in pale stone) and the six medium-rise, late-modern buildings that surround it (sheathed in a veneer of rough-cleft Roman travertine blocks, enameled-aluminum paneling, and vast expanses of glass) run the coloristic gamut from white to off-white to beige. Even when the sun is only halfway to its zenith, dark glasses become necessary equipment. The initial irony of this shrine to the visual arts is that after the exhausting act of getting there, you cannot see it without squinting.

The Getty Center is a multi-use complex made up of the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Conservation Institute, the Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, the Education Institute for the Arts, the Information Institute, and the Getty Grant Program, as well as offices for the Getty Trust, an auditorium, a restaurant pavilion, and a stone-ramparted helicopter landing pad. All of it was designed by Richard Meier, the New York architect whose successful thirty-five-year career has been built on his expertly handled variations on Purist themes first set forth by Le Corbusier seventy-five years ago. To those familiar with Meier’s sleek and self-assured style—modern academicism of a high order—the Getty scheme is a veritable compendium of all his major conceptions and minor motifs, an abridged version of his complete works.

Advertisement

We can see phantom reflections of Meier’s High Museum of Art of 1980-1983 in Atlanta both in the Getty Museum’s entry hall rotunda and in the circular exterior of the Research Institute, where visiting scholars will be working. The architect’s Atheneum of 1975-1979 in New Harmony, Indiana, is evoked in the piano-curve façades of several of the Getty structures, as well as in the miles and miles of white pipe-rail banisters that outline the many external stair towers throughout the complex. Corbusier was entranced by the utilitarian forms of ocean liner superstructures, and his nautical references sail on into history at Meier’s Getty.

There is no disgrace in recycling artistic ideas—whether one’s own or others’—and Meier has always aligned himself with the Mainstream Modern Master strategy of developing a successful formula and then sticking with it. That seemed to have worked best for him during the stylistic flailings of the postmodern moment of the 1980s, when his architecture took on an imperturbable quality that could pass for enduring value at a time of faddish change.

Indeed, none of his self-borrowings would matter much if the sum of the Getty Center’s very many parts added up to a satisfying whole. Although modern architecture dispensed with classical notions of harmony, even the most idiosyncratic building in the modern style can have an internal coherence. But the Getty does not. Nowhere on Meier’s more-or-less level 110-acre campus (the only buildable portion of the hilly 742-acre spread) is there a vista of calm and repose, except when one looks past the frenetically overdesigned buildings—with their restless forms and mixture of stone, metal, and glass—and out toward the dazzling views of the Pacific Ocean, the mountains, and the city that stretch in different directions. This, of course, will be perfectly all right with many visitors, who will come, ride the tram, take in the panoramas, grab a cappuccino, and leave without bothering to explore or even enter the museum, as often happens at the Pompidou Center in Paris.

The Getty Center has already been likened to many things: an acropolis, a Crusader castle, and, less flatteringly, a corporate headquarters, a medical center, or, as one L.A. architect put it, “a stack of Deco refrigerator doors.” The point shared by those diverse characterizations is that in some essential way the Getty does not look like what it is—a repository of art, where the treasures of the few can be shared by many. Though there is no current consensus on museum architecture, the tenor of this criticism-by-epithet suggests that for many the Getty simply does not work as an image for the values its officials say they want to promote.

The Getty’s aloof remove from the city that lies at its feet was not the responsibility of the architect. The $25-million site—spectacular, prestigious, and wholly unsuitable for easy public access—was decided upon by the Getty Trust before Meier was chosen. In The J. Paul Getty Museum and Its Collections, one of several celebratory publications marking the official opening on December 16, the museum’s director, John Walsh, and Deborah Gribbon, its associate director and chief curator, write that the location was intended to bring the institution, previously housed at J. Paul Getty’s hillside Malibu estate, “closer to the population of the city” and attract “a broadened audience.” The new Getty is indeed relatively nearer to more people than the Malibu site, and it is flanked by one of the most heavily traveled roads in California. But it is doubtful that many communities in the multiethnic city will see the museum as welcoming or its architecture as inviting, even with the intense “outreach” campaign it has been conducting in the weeks before the opening.

Among the members of the committee who selected the three finalists in 1984 (the ultimate choice was made by Getty officials) was Ada Louise Huxtable, former architecture critic of The New York Times and a longtime juror of the Pritzker Prize for Architecture, which Meier won several months before he was given the Getty commission. In an essay for Making Architecture: The Getty Center, the second volume of the official account of the project, Mrs. Huxtable shifts roles from critic to advocate as she rather defensively writes:

…There is no culture that has not placed its best buildings high, that has not directed its ambitions to the sky. The Center’s critics—they come with the territory and are present from the start—see only a monument at a time when monuments are out of favor; the wall visible from the freeway below is “exclusionary,” the elegance of the architecture “elitist,” and the Getty agenda of education, conservation, research, and scholarship in the arts “paternalistic.” The politically correct clichés of the moment come easily and will probably die hard. For many, however, this kind of building, in [the critic Colin] Davies’s astute definition, represents “a vigorous commitment to a program or principle” carried out in “top-drawer architecture.”

In addition to the historical misconception that all cultures have equated lofty purposes with elevated sites, Mrs. Huxtable’s belief that monuments are currently out of favor is also unpersuasive, especially in view of the very conspicuous one just opened in Spain only two months before the Getty. Much of the praise of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao has to do with how imaginatively he has recast the notion of architectural monumentality in ways the Getty and its advisers never dreamed of when they chose Meier.

Advertisement

Now that the Guggenheim Bilbao is seen by many critics as a masterwork of late-twentieth-century architecture, it is instructive to recall that designing the Getty Center was once widely regarded as the dream commission of our time. But the Big Rock Candy Mountain that was to sustain a career for years and guarantee lasting fame and fortune turned out to be, as Meier himself describes it, an endless bureaucratic boondoggle.

Meier’s tribulations are recorded in his fascinating memoir of the project, Building the Getty, a fitfully revealing document that is by turns a professional autobiography, an exercise in spin control, and postpartum score-settling. Though Meier comes across as a sore winner—and Getty officials must be mortified—the book does accurately portray the kinds of problems that even eminent architects face as a matter of course but that were in this case magnified by the scope of the project.

2.

The Getty’s architectural selection process was not, strictly speaking, a competition, in that it did not require the thirty-three invited participants to present prospective schemes. Instead, candidates were interviewed to determine their attitudes toward the project, and their previous buildings were assessed (and, in the case of the seven semifinalists, visited by the committee). One reason for this more speculative approach was that the officials of the J. Paul Getty Trust, beneficiary of the oil tycoon’s $700-million bequest (which grew to $1.7 billion when Texaco bought Getty Oil in 1983), had little idea of what they wanted. The old Getty Museum, an approximate replica of the ancient Roman Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum, completed in 1974 on the expatriate billionaire’s Malibu ranch, was a much-visited oddity but clearly inadequate for the leap into the international big leagues envisioned by Harold M. Williams, a former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission who was named in 1981 president and chief executive officer of the Getty Trust.

The broad spectrum of approaches the Getty considered ranged from the ascetic Minimalism of the Mexican master Luis Barragán and the flashy commercialism of the California firm Welton Becket to the postmodern Mannerism of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown and the high-tech engineering of Sir Norman Foster. Also among the first group of thirty-three, but not the semifinalists, was the L.A.-based Frank Gehry, who by 1984 already had a strong following in avant-garde art and architecture circles, if not the international superstar status he now enjoys.

The more conservative members of the committee must have considered Gehry’s exuberantly unconventional aesthetic to be antithetical to the sympathetic display of the Getty’s traditional holdings—primarily Old Master paintings and Grande Epoque French decorative arts. (The Getty’s Greek and Roman antiquities, it was eventually decided, were to remain at the Malibu villa, which is being remodeled by the architects Rodolfo Machado and Jorge Silvetti, and will reopen to the public in 2001.)

There are now good reasons to question why Meier was considered most suitable for the Getty job. For example, his contract with the Getty Trust stipulated that he not design one of his typical all-white schemes. Why, then, go to an architect who has done nothing but such work for decades? In the end, the exterior glare of the Getty Center as built is so strong that his slight modulation of tone, to off-white and beige, is of little consequence.

Even more pertinent is Meier’s sense of the relation between art and architecture. Unlike most other architects, Meier has long harbored aspirations to being a painter, sculptor, and collagist, occasionally exhibiting his works. Like many of his co-professionals, Meier apparently does not want works of art to give his buildings undue competition. In one of the most revealing passages in his book, he rails against the Getty’s decision to ask the artist Robert Irwin to design a garden for the Center. “What was most difficult for me in this whole affair,” he writes, “was that Irwin was being treated as an artist while I was being relegated to the secondary status of architect.”

Meier has always made much of his love for contemporary art—he has long been a friend of Frank Stella’s—but his feelings toward the traditional works in the Getty’s collection seem to have been quite another matter. In Building the Getty, Meier admits that when he went to Malibu to review the museum’s holdings, he found the collection to be “an eccentric and oddly disjunctive combination,” sentiments one can be certain he did not share with his potential employers.

During the 1980s, a decade of unprecedented museum-building activity, Meier began to specialize in that growing sector of practice. Before he received the Getty commission he had already been hired, between 1979 and 1982, to design the Frankfurt Museum of Decorative Arts, the High Museum in Atlanta, and an addition to the Des Moines Art Center. Those projects gave him the specific experience that clients want to be assured of before awarding a major project, the circular thinking being that only someone who has already designed a museum is qualified to design a museum.

In fact, Meier’s first two museums do not serve either paintings or the decorative arts very well. The picture galleries of the High Museum are treated as subsidiary spaces shunted off from the proportionally dominant, glass-paneled entry rotunda, which is flooded with daylight and unusable for the display of works that require careful conservation.

The Frankfurt Museum of Decorative Arts is a handsome building, which takes its cues from the riverside Biedermeier villa next to it, and it is well-integrated into an overall scheme for a group of small museums. But in Meier’s gleaming white galleries, the museum’s collection of traditional German furniture and household objects (walnut wardrobes, stoneware jugs, and the like) is diminished by the perfectionist, clinical setting, and looks dingy. It is quite likely that the alarming effect of this installation prompted the Getty Museum staff to push for the appointment of a traditional interior design specialist to prevent a similar outcome in Los Angeles.

Accordingly, in 1989 the eclectic, French-born, architecturally trained decorator Thierry Despont was hired to design the Getty Museum’s decorative arts galleries, which have a particularly fine collection of French furniture, and he subsequently moved on to choosing the background materials and colors for the picture and sculpture galleries as well. Meier was understandably angry, and indeed this misalliance was not unlike what might have occurred in the 1960s if the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth had brought in Stéphane Boudin, that period’s master of the French grand manner, to decorate the architecture of Louis Kahn. Despont does not have Boudin’s talents, and his rooms devoted to eighteenth-century interiors at the Getty are objectionable not only because they seem bizarrely at odds with Meier’s architectural setting but also because of their inherent vulgarity.

Despont’s hand, however, is not unwelcome in the picture galleries, where subtle background colors—ranging from light gray-green to rich brown—of fabric and paint generally show off the paintings to good advantage. Most successful of all are the tinted plaster finishes of the sculpture galleries. To cite once more the precedent of the Kimbell—the Getty’s closest analogue in its combination of a building by a major contemporary architect and an important collection of traditional artworks acquired in recent decades—there is no reason why Old Master art cannot be shown against walls that do not attempt to mimic those of European palaces.

And though Meier’s talents are not of the same order as Kahn’s, the painting and sculpture galleries work well for visitors in their layout and lighting, and in the way they are set up in a series of pavilions to allow frequent breaks from the long room-after-room march typical of many other museums. Some of the rooms are strangely proportioned—one vertiginous, 45-foot-high sculpture gallery dwarfs its contents, for example—but overall the museum is the best part of the Getty complex. Most of the rest feels uncomfortably like the command post of a multinational conglomerate.

Why, then, was Meier chosen in the first place? There is always an unspoken personal aspect to the selection of any architect, not surprising in an art form so dependent on personal and social relations. As the late architecture critic Reyner Banham, a member of the first Getty committee, wrote in an article that appeared shortly before Meier was named,

…the real, hidden agenda behind most architectural competitions is not so much to pick a design as to pick a designer…. In the two days of heavy interviewing and discussions, we came back to the personalities again and again.1

Or, as Banham put it even more pointedly in private conversation at the time, “It will come down to whom the Getty wants to eat with for the next ten years.” His implication was that among the three finalists, neither the proper but rather stiff Fumihiko Maki nor the cantankerous Sir James Stirling (who died in 1992) was likely to be seen as an ideal long-term dinner companion.

Then there was the apparently pivotal role of Nancy Englander, the Getty Trust official who was in charge of “program analysis” and served on the nine-member committee that chose Meier from among the three finalists. (She and Harold Williams were also the non-voting members of the earlier group that selected the semifinalists.) According to a former close associate of Meier’s, Ms. Englander, a friend of Meier’s, “exerted enormous influence” in the ultimate decision to hire him. She left her position at the Getty in 1986 and later married Williams.

Meier is an architect of unquestionable gifts, and yet over the course of his career he has chosen to husband his skills with such cautiousness that his consistency now seems mere predictability. Ostensibly careful not to put a foot wrong, he has taken a narrow path that led him to the Getty, but once he got there he was unable to find much by way of fresh inspiration.

From the Getty’s institutional point of view, the combination of dependability and the lack of surprise in Meier’s work proved ideal. The Getty foundation does many admirable things: it publishes an important series of scholarly art history books and sponsors the most advanced research in the restoration and preservation of art objects. It distributes previously inaccessible archival material through computer technology, including, for example, the complete papers of Frank Lloyd Wright. (Use of that archive in Arizona had long required payment of an hourly research fee, a practice that inhibited Wright studies for many years.) Among academicians in art history and the humanities, an offer to become a fellow at the Getty Research Institute, with its immense library, ample services, and the agreeable climate of Southern California, is regarded as the intellectual’s equivalent of winning the lottery.

But the Getty is also a bureaucracy, and it is quite likely that the prevailing opinion was that no one’s position at the Trust would be adversely affected if Meier were in charge. But he wasn’t, exactly. Many outside forces bore down on him during the planning and design phases of the project. They came from the Getty’s competing fiefdoms; from the Brentwood Homeowners’ Association, which exerted heavy political pressure on local zoning agencies to restrict the bulkiness of the buildings; and from the various consultants that the Getty Trust retained to oversee the complex operation (including a “work therapist”). It is little wonder that the Getty Center metamorphosed into Meier’s camel, the proverbial beast designed by a committee.

In Building the Getty, Meier recalls his initial dismay at being told he would have to meet at intervals with a Getty design advisory committee. “I slowly realized this was the way the Getty Trust liked to work. While it may have suggested a certain lack of confidence, one of its primary effects was to forestall criticism by outside specialists.”

With checks and balances in place to allow ample second-guessing about what Meier might do, Getty officials no doubt felt confident about the ultimate outcome. The architect, however, now seems plagued by second thoughts, which give his largely self-serving history of the project an unexpected poignance. “Looking back,” he writes, “I have to ask myself whether the Getty selection committee was under some misapprehension that I would perhaps be the most malleable of the finalists.”

3.

Apart from its architecture, the new building offers the first opportunity to assess the full extent and quality of the museum’s holdings. For during the same period in which the Center was designed and erected, the museum pursued one of the most ambitious art-buying programs in recent memory. Although important works were put on view in the old building soon after they were acquired, the opening of the new galleries provides the first occasion to consider how well the Getty’s many highly publicized purchases—including three of the ten most expensive pictures sold at auction during the boom of the 1980s—coalesce into a collection.

The first goal set forth by John Walsh and his curators in a 1984 report to the Getty Trust was to

Get the greatest and rarest objects. If nothing is more important to a museum than its collection, nothing is more important to its collection than the great object that gives measure to the rest. There are not many such works left, but it should be our top priority to secure them.

Despite the Getty’s vast resources, that aspiration apparently was not so easy to fulfill. In their somewhat apologetic introduction to the chapter on paintings in The J. Paul Getty Museum and its Collections, Walsh and Gribbon list the problems that even huge amounts of money seemed unable to resolve.

…Not only have the finest works been rare and expensive, but they have often been subject to the export controls of European countries. This effectively means no exports at all from Italy and Spain; great difficulty in France, Germany, and the Netherlands; and increasing trouble in Britain….

…The Italian Renaissance…is practically a mined-out vein….

It has been even more difficult to find paintings by the Netherlandish and German painters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries….

We had imagined it would be possible to buy major pictures by the greatest artists of eighteenth century France—Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard, Greuze, Chardin—but to our surprise, very few of these have been available.

Now that the Getty collection has at last been assembled with all its much-heralded highlights in place, one can say that despite several big exceptions among the Old Masters—including a powerful gold-ground Daddi triptych, Pontormo’s noble Halberdier, and Rembrandt’s meditative St. Bartholomew—the museum is strongest in nineteenth-century paintings, with three pictures by David that form one of the finest such ensembles outside France; a powerful Goya bullfight scene; a monumental Cézanne still life; and one of the landmarks of nineteenth-century art, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 by Ensor. Furthermore, the Getty’s extensive photography holdings are of very high quality, especially the collection assembled by the pioneering tastemaker Sam Wagstaff.

The Getty certainly matches the excellence of many other American museums, and it marks a tremendous advance for Los Angeles, if for no other reason than it gives the region an internationally important art collection open to the public. Less ambitious in scope, less abundantly endowed, and less imposingly housed than the Getty, the Norton Simon Museum (the old Pasadena Art Museum, which Simon rescued financially and renamed for himself in 1974, the year the Getty Museum in Malibu opened) nonetheless has a number of much-admired Old Master pictures in its collection. On occasion the Simon and the Getty have jointly bought important works—including Poussin’s celebrated Holy Family at Rest on the Flight from Egypt from the Duke of Devonshire’s collection—and the museums exhibit them on a rotating basis.

The Simon’s president, Jennifer Jones Simon (the former movie actress and widow of the museum’s namesake), was a member of the Getty board of directors from 1984 to 1991. Harold Williams, the Getty Trust’s president and CEO since 1981, was the longtime head of Hunt Foods, the basis of Norton Simon’s fortune. He also served on the Simon Museum board from 1979 to 1991. Exploratory talks held several years ago discussed the possibility of the Getty’s absorbing the Simon in its entirety, but nothing came of those discussions.

It says a great deal about the state of civic benefaction in late-twentieth-century America that communities as rich and populous as Los Angeles and Dallas-Fort Worth have had to depend on heavily endowed private foundations to provide their citizens with worthy collections covering the history of art. The Getty (unlike the Kimbell, which has somehow managed to keep its finances out of the headlines) can be quite touchy about how much it pays for things, and its spokesmen have tried to dispel the notion that the Getty’s financial power has adversely affected the art market. Why, then, has the museum been drawn, mothlike, to works that concentrate attention on how much they cost?

Most notorious is the Getty’s Irises by Van Gogh. At the time the picture was sold at Sotheby’s in New York in 1987—to Alan Bond, an Australian wheeler-dealer who was unable to complete the purchase—it fetched $53.9 million, then an all-time auction record for a work of art. The Getty bought the painting in 1990 through private negotiations for an undisclosed amount generally believed to be less than the price Bond had bid. Even if we assume that the price was considerably lower than the one Bond paid, the cost was still very high. The purchase suggests a departure from the more demanding kinds of works that the Getty has hitherto favored. In addition to its art-historical merits, Irises is a sure-fire crowd pleaser, and it seems likely to have been chosen for that very reason at a time when the Getty’s anxieties about its popular appeal began to mount.

4.

Concerns that all the money in the world still could not insure all would go well with the new Getty were apparent in an astonishingly candid interview recently given by Barry Munitz, chancellor of the California State University system and, before that, an executive in a Houston holding company specializing in mergers and acquisitions. In July he was chosen as the new president and CEO of the Getty Trust, to succeed Harold Williams, who retires in January.

According to Munitz,

There’s a void out there in arts and humanities education in a society that’s just so increasingly technical and decentralized and dehumanized. There’s a void that I’m convinced the Getty should try to fill…. The Getty by its strengths and its financial resources should be one player in healing this wound…, a large public institution whose mission is socio-economic mobility, urban outreach, global transformation.2

To underscore the fact that this dramatically reconceived and more socially active role for the Getty is not only his but is shared by his board of trustees, Munitz added,

Most people assume that [the Getty] doesn’t want that role. I do, and the board has said to me, “Come in and help us do this.”

A different allocation of assets is also on Munitz’s mind.

Many people in the art world have said that in the last fifteen years the Getty has become a very good museum, but because of the money spent on the new building, funds were consumed that could have been used to make it a great museum.

Now that the Getty’s architectural adventure is over, however, he foresees a different approach to spending.

Clearly we will continue a commitment to acquisition. In some ways it will even strengthen, but it may be in strategies not just for acquisition, but for contributions, for complex lending, for partnering with other major organizations. I don’t know if we have been, but in the future we will not just be out there tossing money around for the sake of building the collection.

It is unclear whether he would include in that latter category the Getty’s latest major purchase, made earlier this year just before his appointment, of a typically cool and cerebral Poussin landscape for $25.6 million when the Getty already had another very fine picture by this artist.

One familiar aftermath of museum-building projects is for an institution to complain, soon after completion, that its new facilities are still not large enough for its needs. The Getty is not immune to this reaction. According to Munitz,

Even with all the expansion, there really isn’t room for the large temporary exhibitions that people in Los Angeles aren’t getting anyplace else. And there clearly isn’t a lot of room to expand….

It clearly cannot be outside of our mission and it clearly cannot all be met on our site. Therefore we have to partner up with other exhibition spaces around the world, but particularly in Los Angeles—Exposition Park, for example. That museum complex, other exhibition spaces and public spaces around the city will have to be engaged and interacting with the Getty. And the technology, the out-reach, the digitalization, the school visits, the visits to schools, the websites, the videos, the CD-ROMs.

That final litany is already part of many other American museums’ efforts to expand their audience and income in response to devastating cuts in government and corporate funding for the arts. More surprising is the idea that the Getty feels it must take on the added role of Kunsthalle. In fact, although the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has a negligible permanent collection of paintings, it has originated a number of commendable exhibitions and maintains a very good record of bringing important traveling shows to the city. Its spacious changing exhibition galleries function quite well enough on those occasions. It could be that Munitz and his board fear that after one visit to their mountaintop, the average visitor will not be inclined to return without the incentive that a blockbuster special event supplies.

The Getty’s painstakingly considered, meticulously overseen, and exactingly executed new premises were planned with everything in mind, it seems, except growth and change. Locked into its physical and institutional eminence, the Getty now feels it must reassure the public that it is not as remote as it seems and will even, now and again, descend to the lowlands, the better to connect its activities with the life of the community.

No assessment of the Getty, regardless how brief, is complete without a reference to the project’s cost of $1 billion. In a country that proposes to spend $2 billion on a single B-2 bomber, the Getty Center seems cheap at half the price. The other figure of note, of course, is the thirteen years it took to build the Center. Architecture traditionally has been the slowest of art forms. It was not unusual for great cathedrals to take centuries to complete, with stylistic changes from Romanesque to Gothic or Renaissance to Baroque as common as the addition of chapels or spires. But because the function remained the same, the form could be flexible and its growth organic.

Thirteen years, then, is an instant in architectural time. And yet the Getty Center, even as it opens, already seems dated. Conceived amid the certitudes of 1980s prosperity and conspicuous consumption, which it echoes in its extravagant architecture, the Getty arrives on the world cultural stage with more than a touch of the relic about it; yet it lacks the intimations of immortality its sponsors so clearly intended.

This Issue

December 18, 1997