To the Editors:

While I understand well that it is part of the idea of “facing up to things as they are” that might have led to your periodical publishing Richard L. Garwin’s “The Many Threats of Terror” [NYR, November 1], I also think that those of you in charge should become aware of something that you seem to have missed since the destruction of the twin towers. We are at war with terrorists. This is more serious than a parlor discussion in which people can knit their brows and shudder as the horrible possibilities for mass murder are laid out, which can later be described at yet another cocktail gathering as “enlightening but disturbing, so disturbing.”

We are, after all, not talking about numbers; we are talking about thousands, even millions, of people who actually could be killed by forces that have no reservations about sex or religion or color or class or age. If you live in the United States, you easily qualify for slaughter. Start of rationnale; end of rationale. So it seems disgustingly remarkable that those enemies within our borders, when brainstorming in search of the best ways to murder as many civilians as possible, need only turn to our “expert” hucksters of dread and hysteria. They can see them boobing their speculations about indefensible targets from station to station on television, or read articles like Garwin’s to replenish their strategies of mass assassination.

At some point, freedom of speech, common sense, and public responsibility need to fuse—not in the interest of digging a hole large enough to fit one’s head into, not in the interest of beating down “the people’s right to know,” but in the interest of recognizing that the sobering dictates of war have something to do with cunning and with silence of the sort that never allows those who would destroy us to use more of our bloody imaginations than they already are.

Stanley Crouch

New York City

Richard Garwin replies:

I certainly agree with the writer that we need to watch both what we say and what we do in order to avoid providing terrorists with information that might help them do their job better. And it is not only those who committed the atrocities of September 11 who are in the wings; there may be others.

My purpose in writing, however, was not to explain things that such people don’t know already. It was to recognize that many of the remedies for our vulnerabilities lie in our own hands. We can, for example, protect ourselves with personal hygiene, with care, and (especially in the case of anthrax or other biological warfare agents) by maintaining positive pressure of HEPA-filtered air in our buildings.

I have tried for thirty-two years to persuade the US government to do this, without success. I have tried for a good many years to persuade individual national laboratories to do this—again without success. I think that it will finally be done; and I hope it will happen before vast numbers of people fall prey to airborne infection. But such protective measures will not be taken unless people themselves—individuals, managers, owners, and insurance companies—recognize that there are such solutions and insist that they become the norm.

Incidentally, when I was a member of the President’s Science Advisory Committee in 1970, I objected to the proposed elimination of smallpox vaccination in the United States. Smallpox had been “exterminated” as a naturally occurring disease, but it was almost certain that beyond the two legitimate stocks preserved in the United States and in Russia, other samples were still available. Unlike anthrax, smallpox is contagious and would cause untold damage. The arguments for eliminating vaccination had to do with the tiny fraction of damaging effects from such vaccinations—deaths in the range of a few per million persons. This is a penalty I would willingly pay for myself and my family, and one I believe our society would have been willing to pay in order to eliminate the vulnerability that was sure to come, and now exists.

If your correspondent could find some way to solve such problems without alerting people to their existence, I would certainly prefer that approach. But he is asking the impossible.

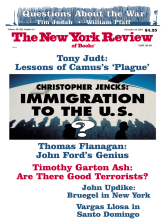

This Issue

November 29, 2001