America’s first immigrants, the ancestors of today’s Indians, came from North Asia at least 13,000 years ago. They spread quickly across North and South America, but their numbers remained low. In 1600 Western Europe had at least ten and perhaps a hundred times more people per square mile than what is now the United States.1 Once Northern Europeans began to appreciate the military and economic implications of this demographic imbalance, a second wave of immigrants started coming to America. By 1700 roughly 250,000 Northern Europeans were living along the Atlantic coast. By 1890 Northern Europeans and their American descendants had spread across the entire continent and numbered more than fifty million.

Migration from Northern Europe slowed after 1890, but the growth of American manufacturing had already begun to attract a third wave of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. This wave peaked just before World War I and ended in 1924, when Congress established strict quotas based on national origin. In 1965 Congress adopted a new system of quotas, which admitted some people with scarce skills, some political refugees, and a lot of people with relatives in the United States. This new system led to a fourth wave of immigration from Latin America, the West Indies, and Asia. This wave has grown steadily since 1965. If it continues to grow at the same rate, post-1965 immigrants and their descendants will make up almost half the total population by 2050.

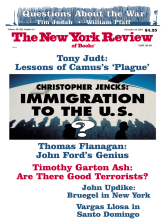

The revival of immigration poses many questions, but I will concentrate on only three. Here I discuss what recent scholarship can tell us about the way successive waves of immigrants have affected the people already living in the United States. A subsequent article will discuss how the children of recent immigrants are doing in the United States and why Congress has let the number of immigrants keep growing.

1.

Large-scale immigration seldom leaves a region’s native population untouched. Soon after the first Indians’ arrival, most large North American mammals, including mammoths, saber-toothed tigers, and camels, disappeared. Some experts blame these extinctions on climatic change. Others blame the Indians, who are said to have engaged in overhunting. Shepard Krech, an anthropologist at Brown University, assesses this long-running controversy in The Ecological Indian. Krech thinks that climatic change is a somewhat more plausible culprit than overhunting, but the issue is far from settled and new evidence keeps emerging.2 In any event, even those who blame the extinctions on climatic change agree that hunting reduced the life expec-tancy of many North American mammals. Given a choice, these mammals would surely have voted to send Homo sapiens back to Siberia.

Immigration from Europe clearly had catastrophic effects on the Indians. In 1492 the Indian population of today’s United States numbered at least two million. Krech guesses that the number was probably more like six million, and some writers propose even higher figures. By 1910, when the US Bureau of the Census made its first serious effort to count the Indians, it found only 266,000. This demographic disaster appears to have been caused mainly by the introduction of European diseases, although war, malnutrition, and marriage with whites also had a part.

Krech suggests that Indians usually welcomed European traders, who were a source of weapons, tools, blankets, and alcohol. But Europeans were also a source of smallpox, measles, influenza, and many other diseases to which the Indians had little resistance. Had the Indians known more about epidemiology, they would presumably have quarantined or killed every European they encountered; but they kept trading and kept dying. Once Europeans began establishing agricultural settlements and making land claims, Indians came to see them as a serious threat. But the Indians still lacked the political unity, the military technology, and the absolute numbers they would have needed to seal their borders. So European settlers kept coming, and in less than three hundred years the Indians’ way of life was destroyed.

When Southern and Eastern Europeans began entering the United States in large numbers, Northern Europeans also felt threatened. This time, however, the natives were more numerous, better organized, and better educated than the immigrants; so instead of worrying about being pushed onto reservations, the natives worried that the new immigrants would undermine the institutions and traditions that had made America so successful. American workers also worried about immigrants taking their jobs. Taken together, these fears generated broad national support for a more restrictive immigration policy.

The depression of the 1890s sparked the first serious efforts to restrict immigration from Europe. Had Congress seen the problem primarily as a matter of economics, the obvious solution would have been to suspend immigration until the labor market tightened. But because so much anti-immigrant sentiment derived from the change in immigrants’ national origins, Congress took a different tack. In 1897 it voted to exclude immigrants who were illiterate. Grover Cleveland vetoed this proposal, which would have cut immigration from Eastern Europe by a third and immigration from Southern Europe by nearly half. The literacy test was revived regularly, but it did not pass until 1917. Quotas based on the national origin of European immigrants were passed in 1921. These quotas were sharply reduced in 1924, virtually ending immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Advertisement

There is little evidence that immigration caused unemployment, as many American workers feared, but there is evidence that it impeded the growth of blue-collar workers’ wages. Claudia Goldin, an economic historian at Harvard, has shown that between 1890 and 1915 wages grew more slowly in those American cities where the proportion of immigrants grew fastest.3 Some historians have argued that immigration also led to ethnic conflict among workers, making union organizing more difficult. Because labor was weak, politicians favored owners over workers, keeping the overall distribution of income extremely unequal. Some circumstantial evidence supports this view. When the proportion of recent immigrants in the labor force declined during the 1930s and 1940s, unions grew stronger and the distribution of income became more equal. New Deal legislation favorable to the labor movement, as well as the social consequences of World War II, also played a central part in these changes, but curtailing immigration may have made unionization easier.

In the 1920s, however, labor was weak and national origin quotas would never have passed without overwhelming support from rural America and much of the urban intelligentsia. Many opponents of immigration were just cultural conservatives who preferred living in a country where everyone spoke a familiar language, attended familiar churches, and followed familiar customs. But some restrictionists took a more apocalyptic position. They argued that the United States had prospered only because its early settlers brought their English customs and institutions with them. These “principled” restrictionists expected the new immigrants to make America more like Southern and Eastern Europe: undemocratic, corrupt, impoverished, and ignorant. They saw the rise of urban political machines such as the Irish-controlled Tammany Hall as a foretaste of what lay ahead for the nation as a whole. Except in the case of urban politics, however, these fears were not realized. Far from making America more like Southern and Eastern Europe, the new immigrants blended with their Northern European cousins surprisingly quickly, and the country as a whole became richer, better educated, and more democratic.

2.

Sociologists have traditionally viewed ethnic assimilation as a matter of generations. The immigrants themselves are the first generation, their children are the second generation, and their grandchildren are the third. Because many habits and attitudes are hard to change after adolescence, first-generation immigrants seldom assimilate fully. Southern and Eastern Europeans who came to America as adults usually continued to speak their native language at home, for example, and they seldom became as fluent in English as in their native tongue. The second generation almost always spoke fluent English. Many other measures of assimilation followed a similar pattern.

One reason second-generation Southern and Eastern Europeans almost all became fluent in English was that while they were very numerous, they had no common language. No linguistic minority dominated any large American city the way Spanish speakers now dominate Miami, for example. Furthermore, while the new immigrants often lived in ethnic neighborhoods, they still needed some English at work, and they could see that their children would need even more English if they were to get ahead economically. As a result, they almost all sent their children to schools conducted entirely in English.

Religion remained a divisive issue far longer than language. The new immigrants almost all wanted their children to learn English, but relatively few wanted their children to become Protestants. Fortunately, America already had a legal system for protecting sectarian diversity. Nonetheless, the specter of Vatican political influence haunted some American Protestants until the 1960s. Only after John Kennedy became president and nothing happened was this specter banished. Neither major party nominated a Jew for national office until last year, but now even that taboo seems to have evaporated.

Intermarriage is probably the best measure of social and cultural convergence. Initially, Italian immigrants usually married other Italians, Polish immigrants usually married other Poles, and so on. But ethnic intermarriage rose sharply in the second generation, and by the third generation it had become the norm. Americans of Southern and Eastern European descent born between 1916 and 1925 were usually the children of immigrants. Those born between 1946 and 1955 were usually the grandchildren of immigrants. If we compare these two cohorts, the proportion marrying outside their own ethnic group rose from 43 to 73 percent among Italians, from 53 to 80 percent among Poles, from 74 to 91 percent among Czechs, and from 76 to 92 percent among Hungarians.4

Intermarriage made the American melting pot genetic as well as cultural. People from different parts of Europe often have distinctive physical features, and at one time writers such as Gobineau tried to divide Europeans into distinct races. The Holocaust discredited such ideas, but blond Italians and swarthy Swedes remain atypical. In America, in contrast, ethnic intermarriage redistributed such physical differences in unpredictable ways, reducing their symbolic significance. When white Americans talk about ethnicity today they are usually talking about religion, holiday rituals, or cuisine, not physical differences.

Advertisement

One reason cultural differences between the descendants of old and new immigrants diminished so quickly was that Northern Europeans from rural America were also moving to America’s cities during the first half of the twentieth century. Both groups found that the rules they had learned from their parents were often inapplicable in this new environment. The anonymity of urban life offered the migrants and their children more personal freedom than the small communities from which they came, but urban jobs demanded new forms of discipline. Newspapers, magazines, movies, soap operas, and popular music offered the entire uprooted urban population new dreams, new ideals, and new rules for everyday living. Because these commercial enterprises wanted the broadest possible audience, they emphasized the things that their audience had in common, not the things that divided them.

Assimilation also proceeded quickly because the economic gap between immigrants and natives was far smaller than today’s folklore suggests. Most immigrants were poor, but so were most natives. Northern Europeans held most of America’s best professional and managerial jobs, but they also held most of the worst agricultural jobs.5 George Borjas has found that Southern and Eastern European immigrants typically earned about 88 percent of what American-born whites earned in 1910. Even Italians, who were the most disadvantaged major immigrant group, earned 83 percent of what American-born whites earned. Jewish immigrants earned as much as average American-born whites in 1910.6 Many of these immigrants had probably started off in worse jobs than the ones they held in 1910, but most of the Southern and Eastern European immigrants had arrived within the past ten years, so they must have moved up quickly.

The new immigrants prospered partly because they settled in cities sooner than Northern Europeans did. Settling in cities also gave their children an educational advantage. Urban schools were among the best in the nation during the first decades of the twentieth century. Big cities established free secondary schools well before most rural districts did, and city schools also attracted better-educated teachers than rural schools. As a result, the children of Southern and Eastern European immigrants were earning as much as the children of Northern European immigrants in 1940, and both groups were earning a little more than the average American.7

In The Case Against Immigration Roy Beck, a liberal journalist, argues that if Congress had not restricted immigration in 1924, second- and third-generation immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe would have proven much harder to assimilate. (Peter Brimelow, a conservative journalist, makes a similar argument in Alien Nation.8) Assessing this claim is not easy. Even measuring the impact of the immigrants who actually came to Amer- ica has proven difficult and controversial. Measuring the impact of the immigrants who would have come if the law had not changed is obviously even harder.

Although my own instinct is that Southern and Eastern Europe immigrants would have assimilated more slowly if America’s doors had remained open, I have not been able to find any strong evidence for this belief. The children of new immigrants were already learning English before the cutoff. They showed little interest in becoming Protestants even after the cutoff. Those who married after the cutoff were more likely to marry someone from another ethnic group, but that was at least partly and perhaps exclusively because those who married after the cutoff were mostly members of the second rather than the first generation.9 The cutoff may have facilitated economic assimilation, but that is very hard to prove.

3.

America’s current immigration debate often sounds a lot like the debate that raged early in the twentieth century. Once again many American workers see immigrants as an economic threat. Once again many employers see immigration as a way of keeping their wage bills low. Once again the great majority of Americans would prefer to keep the country homogeneous. Once again both immigrants and their supporters argue for the benefits of cultural variety. But while the arguments are familiar, the facts have changed dramatically. The economic gap between immigrants and natives is far larger than it was a century ago, but racial and ethnic differences carry less weight than they did then. Grass-roots opposition to immigration plays a smaller role in American politics than it did a century ago, and the labor movement has recently switched sides—the AFL-CIO concluded last year that it should try to organize immigrants rather than reduce their numbers.

Heaven’s Door, by George Borjas, is by far the best introduction I have seen to the economics of immigration. Born in Cuba, Borjas came to America as a child. (He is also my colleague at Harvard, so skeptics should feel free to discount my enthusiasm for his book.) In 1970, he reports, America’s foreign-born workers earned as much as natives. By 1998 male immigrants typically earned only 77 percent of what natives earned. That makes the wage gap between immigrants and natives three times as large as it was in 1910.10 Immigration from Mexico has had a central part in this change. Mexico’s share of the foreign-born population has risen from 8 percent in 1970 to 28 percent today. Mexican-born men in the United States earn less than half what non-Latino whites earn, so as Mexico’s share of the immigrant labor force grows, the economic gap between immigrants and natives inevitably widens.11 America now accepts more legal immigrants from Mexico than from all of Europe. If one adds illegal immigrants, Mexicans are more numerous than Asians. The Bush administration hopes to expand Mexico’s share even further. It has said that it wants to legalize many of the three to five million “undocumented” Mexicans currently in the United States, as well as increase the number of unskilled Mexicans admitted on a temporary basis.12

Only half the Mexicans living in America have attended secondary school, and only a third have graduated. Only one in eight claims to speak English very well.13 Italians and Poles had similar handicaps in 1910, but Americans are far better educated today than they were a century ago, so the gap between Mexicans and American-born workers is wider. In view of their educational and linguistic disadvantages, Mexican-born workers actually do surprisingly well. Roger Waldinger, a sociologist at UCLA, finds that most California employers prefer Mexicans to the American-born workers who apply for unskilled jobs, because they believe Mexicans are more reliable and disciplined than natives. But while having the right attitude is often enough to get an eight-dollar-an-hour job, it is seldom enough to get one for sixteen dollars an hour.14

Since 1970, immigration has increased the number of unskilled job applicants faster than the number of skilled job applicants. First-year economics predicts that increasing the relative number of unskilled workers will depress their wages, because employers will not need to raise wages to attract applicants for unskilled jobs. Nonetheless, those who favor an expansive immigration policy often deny that the increase in the number of unskilled job applicants depresses wages for unskilled work, arguing that unskilled immigrants take jobs that natives do not want. This is sometimes true. But we still have to ask why natives do not want these jobs. The reason is not that natives reject demeaning or dangerous work. Almost every job that immigrants do in Los Angeles or New York is done by natives in Detroit and Philadelphia. When natives turn down such jobs in New York or Los Angeles, the reason is that by local standards the wages are abysmal. Far from proving that immigrants have no impact on natives, the fact that American-born workers sometimes reject jobs that immigrants accept reinforces the claim that immigration has depressed wages for unskilled work.

When economists first tried to calculate immigrants’ impact on wages, they studied wage changes in cities that had attracted a lot of immigrants. The best-known study of this kind exam-ined the effects of the Mariel boatlift, which brought 125,000 Cuban refugees to Florida in 1980. Half these refugees settled in Miami. Because the Marielitos were relatively unskilled, most economists expected their arrival to increase competition for unskilled jobs, widen the wage gap between skilled and unskilled workers, and drive up unemployment, at least in the short run.

To see if this actually happened, David Card compared changes in Miami after the boatlift to changes in other big Southern cities. Card is a Canadian-born labor economist with a reputation for careful work. He found no evidence that the boatlift had affected either unemployment or wages in Miami.15 Among those who want America to admit more immigrants, Card’s study is often cited as proof that immigration does not harm Amer- ican workers. But as Borjas points out, the Marielitos’ impact on the Miami labor market could have been offset by changes in domestic migration. When American-born migrants were deciding where to go in late 1980 and 1981, they knew Miami had large numbers of Cuban refugees. If American migrants reacted to this information by going elsewhere, the boatlift’s impact would have been spread over a much wider area, leaving footprints too faint to detect.

Many skeptics think this argument requires an implausibly efficient labor market. When big firms close, the local unemployment rate does not return to normal instantaneously. Why should the Miami labor market have adapted so quickly to the Marielitos’ arrival when most cities take much longer to adapt to a sudden labor surplus? Card has also shown that, at least in the 1970s and 1980s, natives were not especially likely to leave areas that were attracting immigrants.16 But one can still argue that these areas would have attracted more natives if the immigrants had not come.

Consider California, which has attracted about a quarter of all American immigrants. California’s share of the American population grew fairly steadily from 1900 to 1990. Until the 1970s California grew by attracting natives from “back east.” After 1970 it grew mainly by attracting immigrants from overseas. It is possible, Borjas says, that “around 1970, for reasons unknown, Americans simply changed their mind about the magnetic attraction of sun, surf, and silicon, and stopped moving to California.” Borjas obviously thinks the influx of immigrants slowed the flow of natives from elsewhere in the United States. I am inclined to agree. But other things were also changing in California.

California housing prices exploded in the 1970s, largely because politically and ecologically acceptable building sites became increasingly hard to find. If nothing else had changed, firms that wanted to attract out-of-state workers would have had to raise wages enough to keep home ownership affordable, which would have made their products less competitive. But because immigrants were pouring into the state, California firms did not always have to raise wages in tandem with housing prices. Many unskilled immigrants were willing to live two or three to a room, and even skilled immigrants were often willing to rent rather than buy. By 1990 California had the lowest home ownership rate in the nation. After 1990 American-born workers left the state almost as fast as immigrants moved in.

From a conventional economic viewpoint, California’s shift to immigrant labor was a success. Employers made money, professional and managerial workers got to live comfortably in a spectacular environment, and eight million immigrants were better off than they would have been in Latin America or Asia.

But this is the winners’ version of history. Many less-skilled California natives would tell a darker story, in which their economic situation deteriorated and either they or their children eventually had to move elsewhere. If California had been a sovereign nation, its voters would almost certainly have endorsed a ballot initiative sharply reducing immigration. Because the state’s immigration policy was set in Washington, the losers had no recourse.

William Frey and Ross DeVol are demographers connected with the Milken Institute in California. In America’s Demography in the New Century, they argue that all the big metropolitan areas where immigrants settled in the 1990s lost native-born residents. The six metropolitan areas that attracted the most immigrants between 1990 and 1998 were (in order) New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. All six metropolitan areas lost natives during the 1990s. Taken together they lost 4.3 million natives, while adding 3.8 million immigrants.

Frey and DeVol expect immigrants to keep concentrating in these metropolitan regions, partly because new immigrants will continue to rely on relatives and members of their own ethnic group to find work and partly because immigrants prefer places where some of the neighbors speak their native language. Frey and DeVol also expect second- and third-generation immigrants to concentrate in these areas. As a result, they think today’s ports of entry will become what the analyst Saskia Sassen calls “global cities,” with strong cultural and economic ties to Europe, Asia, and Latin America.17

Such cities will continue to attract top managers and professionals from every ethnic group. Global corporations can offer challenging, well-paid jobs, and young people with graduate degrees often see ethnic diversity as a cultural amenity.18 Less well educated American-born workers are not so enthusiastic about ethnic diversity, and they see no reason to compete with immigrants if they can avoid it. So they will probably avoid America’s global cities, allowing immigrants to take over most of the less-skilled jobs.

A century ago immigrants went to high-wage cities, while natives often remained in low-wage rural areas. Today, Frey and DeVol argue, immigrants go where their co-ethnics are, while American-born migrants go where wages are highest. In the 1990s American-born migrants’ top choices were Atlanta, Las Vegas, Phoenix, Dallas, Portland, Denver, Orlando, and Seattle. All these places also attracted some immigrants, but only Dallas ranked among immigrants’ top ten destinations.

If unskilled Americans respond to large-scale immigration by moving elsewhere, analyzing wage changes in the cities or states where immigrants settle cannot tell us how immigration affects wages. Instead we have to treat the United States as one big labor market, figure out how immigrants change the national distribution of skills, and estimate the effect of these changes on different groups’ earnings. Borjas shows, for example, that the wage gap between high school dropouts and graduates grew from 30 percent in 1980 to 41 percent in 1995. He estimates that almost half this change was caused by the fact that American-born high school dropouts faced more competition from immigrants than any other group of American-born workers. Whether immigration contributed to the growth of inequality among better-educated workers remains an unexplored question.

4.

Many Americans believe that immigration drives up taxes. This belief is probably correct, simply because immigrants are poorer than natives. Low- income families do not contribute much to the public treasury, but they have pretty much the same needs as everyone else. Their garbage has to be collected, they need some way of getting to work, and their children have to be educated. Indeed, since immigrants have more children than natives, immigrant families typically cost a school district more than native families of the same age.

Because immigrants earn less than natives, they are also more likely to need means-tested government benefits such as Medicaid, food stamps, and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families. Congress limited noncitizens’ right to this kind of public assistance in 1996, but immigrants still receive it more often than natives. Immigrants from Mexico account for most of the difference. In Immigration from Mexico Steven Camarota of the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington reports that 31 percent of Mexican households received some form of public assistance in 1999, compared with only 17 percent of non-Mexican immigrants and 14 percent of natives.19 Mexicans receive public assistance more often partly because they are less skilled than other immigrants, and partly because they are concentrated in California, which has relatively generous eligibility standards.

The National Research Council’s panel on the economic and demographic effects of immigration, which was chaired by the economist James Smith of the RAND Corporation, has estimated the fiscal cost of immigration in California and New Jersey. The committee’s report, The New Americans, concludes that in the mid-1990s California spent about $11,200 a year on the average immigrant household. Immigrant households paid an average of only $7,600 in taxes. The state’s more affluent native households made up the difference, which cost them an average of $1,200 per household.

Although immigration imposes short-term fiscal costs on relatively well-off natives, it also allows natives to buy many services on the cheap. Affluent Californians now rely on immigrant workers to mow their lawns, prepare their fast food, scrape their paint, and care for their children while they go off to more lucrative jobs. Whether immigration cuts the average native’s bills by $1,200 a year I do not know. But it certainly saves the rich a lot more than that.

In New Jersey, where immigrant families are almost as affluent as natives, the taxes collected from immigrants come much closer to covering the cost of the services they receive from state and local government. Immigrants also make up a much smaller fraction of the total population in New Jersey than in California, so their presence costs New Jersey natives only $232 per household, or 0.4 percent of the average native household’s annual income.

Well-to-do taxpayers who want immigrants to pay their way need to keep reminding themselves that the only way all workers can pay their share of taxes is for employers to pay their least-skilled workers higher wages. Replacing immigrants with natives would not solve this problem. If California replaced all its immigrants with natives, the natives would earn a little more. But because the natives would also be eligible for the full range of state benefits, the net effect on the state budget would be fairly small.

The New Americans also suggests that immigration raises profits more than it lowers wages, making America as a whole slightly richer. But as Borjas emphasizes in Heaven’s Door, the net economic gain from immigration is tiny: probably less than 0.1 percent of Gross Domestic Product. The big effects of immigration are on the distribution of income. Under America’s current immigration policy, the winners are employers who get cheaper labor, skilled workers who pay less for their burgers and nannies, and immigrants themselves. The losers are unskilled American-born workers.

The distributional effects of immigration could change in the years ahead. In the late 1990s Congress authorized the Immigration and Naturalization Service to issue more temporary visas to highly educated workers. These workers are not officially counted as immigrants, because they are supposed to go home in a few years. But if past experience is a guide, sending them home will prove politically difficult. Admitting such workers shifts the costs of immigration away from America’s worst-paid workers toward its best-paid workers, who will face more competition when they look for work and will presumably see their relative wages fall. Such a policy also raises the nation’s per capita income and makes the distribution of income more equal.

This year, however, the main choice facing Congress is whether to admit even more unskilled immigrants. If Congress goes along with the Bush administration’s Mexican initiative, unskilled workers’ relative wages will fall, just as they did in the 1980s and 1990s. The adverse effect on African-Americans is likely to be especially marked. In the long run, however, the largest cost of admitting more Mexican immigrants may fall on their children. Many of these Mexican-Americans will earn little more than their parents, and many may feel deeply disillusioned with their new homeland as a result. I return to this issue in a subsequent article.

—This is the first of two articles.

This Issue

November 29, 2001

-

1

Western Europe had between 72 and 90 people per square mile (see Shepard Krech, The Ecological Indian, p. 265). Estimates of the pre-Columbian Indian population range from two to twenty million. If we ignore Alaska, these estimates imply population densities between 0.7 and 7 people per square mile.

↩ -

2

For a recent analysis that supports the overhunting hypothesis see John Alroy, “A Multispecies Overkill Simulation of the End-Pleistocene Megafaunal Mass Extinction,” Science, June 2001, pp. 1893–1896.

↩ -

3

See “The Political Economy of Immigration Restriction in the United States, 1890 to 1921,” in The Regulated Economy: A Historical Approach to Political Economy, edited by Claudia Goldin and Gary Libecap (University of Chicago Press, 1994), pp. 223–257. In their chapter for The Handbook of Inter-national Migration, Susan Carter and Richard Sutch argue that wages grew slowly in cities with high levels of immigration only because immigrants gravitated to cities with unusually high wages, which inevitably fell once their labor shortage was relieved. Goldin shows, however, that the negative relationship between immigration and wages persisted even after adjusting for a city’s initial wage level.

↩ -

4

Between half and two thirds of all spouses from these countries reported that their own ancestry was mixed. The estimates in the text count everyone who said they had any ancestors from a given country. The data are from Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters, From Many Strands: Ethnic and Racial Groups in Contemporary America (Russell Sage Foundation, 1988), p. 199.

↩ -

5

In their chapter for The Handbook of International Migration, Joel Perlman and Roger Waldinger argue that immigrants were more disadvantaged in 1910 than they are today. But like many other writers they exclude the agricultural sector from their comparisons.

↩ -

6

These earnings estimates come from George J. Borjas, “Long-Run Convergence of Ethnic Skills Differentials: The Children and Grandchildren of the Great Migration,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, July 1994, pp. 553–573. They combine occupational data from the 1910 Census with earnings data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Because the Census has never asked about religion, the earnings estimates for “Jews” are actually for first-generation immigrants from Russia, which included most of Poland.

↩ -

7

This calculation is based on data in Borjas’s Industrial and Labor Relations Review paper. I am also grateful to Borjas for providing me with the 1940 mean for natives. In Heaven’s Door Borjas concludes that if immigrants from a given country had low earnings in 1910, three fifths of this disadvantage typically persisted among their children in 1940, but that estimate is heavily influenced by the fact that non-Europeans made little progress between 1910 and 1940. Among Europeans there was considerably more mobility.

↩ -

8

Random House, 1995.

↩ -

9

One way to test the claim that cutting off immigration accelerated assimilation would be to compare the marriage patterns of second-generation Italians, Poles, Czechs, and Hungarians born before and after World War I. If the 1924 cutoff hastened assimilation, second-generation immigrants born after World War I should have had less contact with recent immigrants and should have married outside their ethnic group more often than second-generation immigrants born earlier.

↩ -

10

Borjas estimates that the average immigrant (including those from Northern Europe, Mexico, Canada, the West Indies, and China) earned 92 percent of what the average native white earned in 1910.

↩ -

11

These estimates come from tabulations by Andrew Clarkwest using the March 2000 Current Population Survey. Mexican-born males who worked full-time throughout 1999 earned an average of $23,200. Non-Latino whites averaged $50,000.

↩ -

12

Until recently, the Immigration and Naturalization Services estimated that five million illegal immigrants were living in the United States, of whom perhaps three million were Mexicans. The 2000 Census suggested that there are more like eight million illegals in the United States. If that is the case, the number of Mexican illegals is probably four or perhaps five million, not three million.

↩ -

13

Calculated from David Lopez, “Social and Linguistic Aspects of Assimilation Today,” in The Handbook of International Migration, Tables 11.2 and 11.3. The estimates are based on self-reports collected by the Census Bureau in 1989.

↩ -

14

Roger Waldinger and Michael Lichter, “What Employers Want” (Harvard University, Program on Inequality and Social Policy, September 2000).

↩ -

15

David Card, “The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, January 1990, pp. 245– 257. One partial explanation for Card’s findings is that he looked only at the Marielitos’ impact on nominal wages. A recent study by Albert Saiz, a doctoral candidate in the Harvard economics department, shows that the Marielitos’ arrival drove up rents in Miami (see “Room in the Kitchen for the Melting Pot: Immigration and Rental Prices,” Harvard Department of Economics, October 2000). This finding implies that real wages fell slightly in Miami.

↩ -

16

See David Card, “Immigrant Inflows, Native Outflows, and the Local Labor Market Impacts of Higher Immigration,” Journal of Labor Economics, January 2001, pp. 22–64, as well as David Card and John DiNardo, “Do Immigrant Inflows Lead to Native Outflows?,” American Economic Review, May 2000, pp. 360–367.

↩ -

17

See her The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo (second edition, Princeton University Press, 2001).

↩ -

18

In 1995, 52 percent of American adults with graduate degrees wanted immigration kept at its current level or increased, compared to about 32 percent of those with a BA, 28 percent of high school graduates, and 30 percent of those without high school diplomas (James P. Smith and Barry Edmonston, The New Americans, p. 392). If these differences were rooted in economic self-interest, those without high school diplomas should be far more hostile to immigration than any other group.

↩ -

19

I calculated the number of households receiving public assistance from Figures 3 and 20 of Immigration from Mexico. The estimates are based on what families tell Census Bureau interviewers. Administrative data show that such reports underestimate the fraction of households receiving public assistance. The Census Bureau does not ask whether immigrants are here legally. We do not know how many illegals are included in its counts. In theory, illegals cannot get public assistance.

↩