Americans cannot seem to get enough of Benjamin Franklin. During the past few years we have had several Franklin biographies, of which Walter Isaacson’s is the most recent and the finest; and more studies of Franklin are on the way. Part of the reason for this proliferation of Franklin books is the approaching tricentennial celebrations of his birth in 1706. But this isn’t enough to explain our longstanding fascination. He is especially interesting to Americans, and not simply because he is one of the most prominent of the Founders. Among the Founders his appeal seems to be unique. He appears to be the most accessible, the most democratic, and the most folksy of these eighteenth-century figures.

His many portraits suggest an affable old man with spectacles and a twinkle in his eye ready to tell a humorous story. People seem to feel he is the Founder with whom they would like to spend an evening, quite different from the others. Stern and thin-lipped George Washington, especially as portrayed by Gilbert Stuart, is too august and awesome to be approachable. Although Thomas Jefferson has democratic credentials, he is much too aristocratic and reserved for most people; besides, he was a slaveholder who failed to free most of his slaves. John Adams seems human enough, but he is too cranky and idiosyncratic to be the kind of American hero we can get close to. James Madison may seem too shy and intellectual and Alexan-der Hamilton too arrogant and hot-tempered: neither of them makes a congenial popular idol. It is Franklin who seems to have the common touch and who seems to suggest better than any other Founder the plain democracy of ordinary folk.

Scholars today tend not to believe anymore in the notion of an American character, but if there is such a thing, then Franklin seems to exemplify it. In 1888 William Dean Howells called Franklin “the most modern, the most American, among his contemporaries,” and many other commentators have agreed. He certainly appears to embody much of what most Americans have valued throughout their history. His “homely aphorisms and observations,” the historian Louis Wright has written, “have influenced more Americans than the learned wisdom of all the formal philosophers put together.” Although Franklin was naturally talented, one nineteenth-century admirer declared, he achieved his success by character and conduct that were “within the reach of every human being.” All of his teachings entered into the “every-day manners and affairs” of people; they “pointed out the causes which may promote good and ill fortune in ordinary life.” That was what made him such a democratic hero.

Unlike the other great Founders, Franklin began as an artisan, a lowly printer who became the architect of his own fortune. He is the prototype of the self-made man, and his life is the classic American success story of a man rising from the most obscure origins to wealth and international preeminence. Franklin, the author of The Way to Wealth, stands for American social mobility—the capacity of ordinary people to make it to the top through frugality and industry. The unforgettable images of Franklin that he himself helped to create—the youth of seventeen with loaves of bread under his arms, the scientist flying a kite to capture lightning in a storm, the fervent moralist outlining a code that, once followed, would lead to success—have passed into American mythology and folklore. Not surprisingly, he became for the historian Frederick Jackson Turner and many subsequent biographers and panegyrists “the first great American.”

He was, The Atlantic Monthly declared in 1889, the nation itself, “the personification of an optimistic shrewdness, a large, healthy nature, as of a young people gathering its strength and feeling its broadening power.” He has represented everything Americans like about themselves—their level-headedness, common sense, pragmatism, ingenuity, and get-up-and-go. Because of his inventions of the lightning rod, bifocals, the Franklin stove, and other useful instruments, he has been identified with the happiness and prosperity of common people in the here and now. As one history of the United States put it in 1833, he was the one “who has made our dwellings comfortable within, and protected them from the lightning of heaven.”

Millions of people have quoted and tried to live their lives by his Poor Richard sayings and proverbs, such as “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy wealthy and wise.” Many people seemed to know his writings as well as they knew the Bible. It is not surprising therefore that the book Davy Crockett had with him when he died at the Alamo was not the Bible but Franklin’s Autobiography.

In the nineteenth century, so popular was Franklin’s image as the boy who worked hard and made it that humorists like Mark Twain could scarcely avoid mocking it. Franklin’s example, said Twain in 1870, had become a burden for every American youngster. The great man had

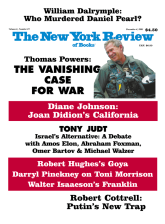

Advertisement

early prostituted his talents to the invention of maxims and aphorisms calculated to inflict suffering upon the rising generation of all subsequent ages. His simplest acts, also, were contrived with a view to their being held up for the emulation of boys forever—boys who might otherwise have been happy…. With a malevolence which is without parallel in history, he would work all day and then sit up nights and let on to be studying alge-bra by the light of a smouldering fire, so that all other boys might have to do that also or else have Benjamin Franklin thrown up to them.

As Twain’s sardonic humor suggests, Franklin has had many detractors. And most of them have been much more devastatingly critical than Twain. Franklin may be the most folksy figure among the Founding Fathers; yet at the same time he is also the one who has provoked the most controversy and the most derision.

Of course, from the beginning of professional history writing at the end of the nineteenth century, historians have been busy trying to strip away the many legends that have grown up around all the Founding Fathers in order to get at the human beings presumably hidden from view. Indeed, during the twentieth century this sort of historical debunking of the Founders became something of a cottage industry. But the criticism leveled at Franklin has been different. Historians did not have to rip away a mantle of god-like dignity and loftiness from Franklin, as they had to do with the other Founders, in order to recover the hidden human being; Franklin already seemed human enough. Indeed, it was his Poor Richard ordinariness that made him vulnerable to criticism. As William Dean Howells noted, Franklin came down to the end of the nineteenth century “with more reality than any of his contemporaries.” Although this “by no means hurt him in the popular regard,” it certainly did not help his reputation with many intellectuals. Precisely because of his identification with middling and materialistic America, he became the Founder that many critics most liked to mock or attack.

Almost from the beginning of America’s national history many intellectuals found that by attacking Franklin they could attack many of America’s middle-class values. All of the things that turned Franklin into a folk hero became sources of genteel contempt and ridicule. In the minds of imaginative writers such as Poe, Melville, and Thoreau, Franklin came to stand for all of America’s bourgeois complacency, its get-ahead materialism, its utilitarian obsession with success—the unimaginative superficiality and vulgarity of American culture that kills the soul. He eventually became Main Street and Babbittry rolled into one—both a prime example of America’s money-making middle class and the patron saint of business.

Franklin became so closely identified with the art of getting, saving, and using money that Max Weber fastened upon him as the perfect exemplar of the modern capitalistic spirit. No one, wrote Weber in his famous work The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904–1905), expressed the moral maxims underlying the ethic of capitalism better than Franklin. Franklin, Weber declared, believed that “man is dominated by the making of money, by acquisition as the ultimate purpose of his life,” and this acquisitive ethic was expressed “in all his works without exception.”

Someone who thought that the end of life was merely the making of money obviously lacked depth and spirituality. And if Franklin was superficial and soulless, so too was America. With his allegedly shriveled spirit Franklin was everything that imaginative artists found wrong with America. And no artist found more wrong with Franklin and America than did D.H. Lawrence. His attack on Franklin in his Studies in Classic American Literature in 1923 is the most famous criticism of Franklin ever written. To Lawrence, Franklin embodied all those shallow bourgeois money-making values that intellectuals are accustomed to dislike. Franklin was a “dry, moral, utilitarian little democrat,” the “sharp little man,” the “middle-sized, sturdy, snuff-coloured Doctor Franklin,” “sound, satisfied Ben,” who was a “virtuous little automaton” and “the first downright American.”

By our own time this sort of criticism is seldom heard, maybe because we don’t see many alternatives to bourgeois values and the making of money. Franklin has now become a figure of fun. A great many Americans imagine him as the jovial lecher depicted in the musical 1776. If my experience taking questions from audiences is any guide, many Americans want to know most about Franklin’s sex life. They imagine a genial old man with twinkling eyes sitting with a woman in his lap, and not just any woman, but a French woman. Still, whatever the popular image of Franklin may now be, there seems to be little doubt that most people take it for granted that he was a thoroughgoing American, indeed, as the title of H.W. Brands’s recent biography suggests, The First American.

Advertisement

Walter Isaacson does not call Franklin “the first American,” but, as his subtitle indicates, he believes that Franklin’s life is “an American life.” Isaacson likes and respects Franklin. The former chairman of CNN and managing editor of Time, currently president of the Aspen Institute, Isaacson treats Franklin almost as if he were one of our contemporaries, an interesting American of great talent and sensible values whom we ought to get to know. It’s almost as if Isaacson projects into Franklin his own enthusiastic, common-sensical, and thoroughly American character. Franklin, he believes, stood for the Enlightenment values of reason and tolerance, for sociability and affability and getting along with people. Franklin was an optimist and consensus builder, someone, says Isaacson, who was “the most influential in inventing the type of society America would become.”

Isaacson’s biography is at least double the size of Edmund Morgan’s recent delightful book on Franklin, and it is almost as much of a celebration of Franklin as Morgan’s brief biography is.1 Isaacson is aware of many of the criticisms of Franklin but believes Franklin’s accomplishments overwhelm any weaknesses he might have had. In his final chapter Isaacson even sets up a moral ledger, as Franklin the bookkeeper might have done. He lists the pros and cons of Franklin’s life on either side and concludes that the pros outweigh the cons. He sensibly points out that Franklin the man should not be confused with the character depicted in the Autobiography or the Poor Richard essays. Franklin was not a penny-pinching proto-capitalist but a generous philanthropist.

Isaacson accepts the image of Franklin as the supreme spokesman for middle-class values. But these values—“diligence, honesty, industry, and temperance”—he says, should be praised in our time, not condemned. So too can Franklin’s utilitarian outlook on religion. We need today, Isaacson says, a lot less religious fervor and more of the religious humility and tolerance that Franklin favored. Franklin may not have been a deep philosophical thinker, he writes, but he was a pragmatic one, very much in accord with the American character. Against those who charge Franklin with being too much of a compromiser instead of a heroic man of principle, Isaacson says that we need more such compromisers and conciliators.

Isaacson has no patience with the intellectuals’ scorn for the ordinary bourgeois values presumably exemplified by Franklin. He fully describes Franklin, faults and all, and spends much of his time on his strained and flawed family relationships, which most other biographers have tended to ignore, particularly his estrangement from his illegitimate son, William Franklin. But he remains overwhelmingly admiring of his subject, while accepting the conventional wisdom about Franklin: that he was a congenial polymath who was the prototypical American.

That conventional view, I believe, makes Franklin less interesting than he really was. If we assume that Franklin was the consummate middle-class American from the beginning, we have trouble understanding some of the most important events of his life, including his decision at age forty-two to retire from business and become a gentleman, his intense ambition to become a player in the British Empire, the belated and personal character of his revolutionary fervor, and the reasons why he began writing his Autobiography in 1771 in the aftermath of his failure to secure a position in the British imperial hierarchy. The first part of the Autobiography was written in a mood of frustration, nostalgia, and defiance. Franklin suggested in the first section of his memoir that he was not really a dependent courtier seeking office at some superior’s pleasure; he was a free man who against overwhelming odds had made it as a hardworking and independent tradesman. Of course, as soon as signals from the British government changed and became more favorable, Franklin dropped the writing of his autobiography and did not resume it until after the peace treaty with Britain was signed in 1783.

Perhaps it is a mistake to believe that Franklin was the quintessential American. After all, he spent most of the last thirty-three years of his life abroad; in fact, he was absent from America for so long that he was reluctant to return, fearing that he would be, as he said several times, “a Stranger in my own Country.” He certainly enjoyed the sophisticated and cosmopolitan worlds of London and Paris far more than the rustic provincial society of America. He hobnobbed with philosophers and aristocrats in Britain and Europe, conversed with kings, and even dined with one. At times it was doubtful whether he would ever return to America, or wanted to—or even cared much about America. It’s not surprising that at several points some of his countrymen suspected that Franklin was a British spy or more loyal to France than he was to America.

Isaacson does not have much to say about the aspects of Franklin’s life that make his Americanness open to question. Like Carl Van Doren sixty-five years ago, he has sought “to bring the whole of Franklin’s life, with all the precise details essential to it, into a single narrative large enough to do it justice.”2 Like Van Doren, he has found little room for details that suggested that Franklin might have been a stranger in his own country. Probably it is Van Doren’s 1938 Pulitzer Prize– winning biography that Isaacson’s book most closely resembles. Van Doren also admired his subject greatly and that admiration suffused his gracefully written eight-hundred-page book. Perhaps because of its veneration for Franklin and the elegance of its prose, Van Doren’s book has remained the most popular biography of Franklin. It is in fact amazing that Van Doren’s book has stood up as long as it has, since there has been an enormous amount of Franklin scholarship since the 1930s. But much of that scholarship has been produced by literary scholars, especially by Alfred O. Aldridge and J.A. Leo Lemay and their students. Over the past half-century scholars of early American literature have written scores of books and articles on Franklin’s many writings, more of which seem to be discovered every day. They have, it seems, explicated virtually every sentence in his Autobiography, interpreting its intentions, evasions, and rhetorical devices, and they have analyzed all the short, sometimes ironic sketches, essays, and bagatelles that Franklin wrote. But because this scholarship has focused largely on the literary quality of Franklin’s numerous works, it has not had as much effect on the historical biographies of Franklin as perhaps it should have. Neither Van Doren nor any of the recent biographies devote much attention to Franklin as a literary artist. Presumably that will be left for Leo Lemay’s forthcoming multivolume biography.

Aside from the literary studies, some of the most interesting Franklin scholarship of the past several decades has dealt with Franklin’s domestic life, especially his relations with his wife and children and other women. In 1975 Claude-Anne Lopez and Eugenia Herbert published their remarkable study The Private Franklin: The Man and His Family, which fully exposed a darker side of Franklin’s treatment not only of William but of his wife Deborah and his daughter Sally. Lopez and Herbert showed, for example, that Franklin spent fifteen of the last seventeen years of his marriage abroad apart from his wife, and ignored her pleas in 1774 to return to America so that she could see him before she died. He refused to attend the weddings of his two children and seemed to enjoy the company of the widow and her daughter with whom he lodged in London more than his own family back in Philadelphia. Since The Private Franklin, Lopez, who for many years was one of the editors of the edition of the Franklin Papers being published by Yale University Press, has gone on to write two other books on Franklin and especially on his affectionate relations with women in France. All of Lopez’s books are models of fair-minded scholarship. Isaacson takes account of much of this recent work on Franklin’s relations with his family. But he reports Franklin’s shabby treatment of his wife and children matter-of-factly, and does not let it detract from his respect for the great man.

Because Isaacson’s biography is admiring of Franklin and is at the same time very readable, it will probably supplant Van Doren’s as the standard single-volume biography of Franklin. The prose and organization of Isaacson’s book are more relaxed and more accessible than Van Doren’s. In his table of contents, Van Doren gave short summaries of the events covered in each chapter, but then left the text itself divided only by Roman numerals, making it difficult for the reader to read selectively. By contrast, Isaacson breaks up his chapters into numerous brief two- or three-page sections with separate headings, so that a reader can jump from section to section and concentrate, for example, on segments dealing with Franklin’s relationship with his family. It is a sensible way of organizing a lot of disparate material in a chronological manner.3

Since Isaacson’s previous work concentrated on late-twentieth-century diplomacy and politics, it is not surprising that some of the best parts of his book deal with Franklin’s diplomacy in Paris. Franklin, he says, was not “a cold realist” like John Adams; he balanced realism with idealism and won over the French court. He not only brought the French monarchy into alliance with the new rebellious republic but he kept badgering Louis XVI’s increasingly impoverished government for loans in support of the American Revolution. That Franklin was able to do all this in the face of the hostility of Adams and his other colleagues was remarkable, and Isaacson is fully and correctly admiring of his achievement.

But what Isaacson doesn’t do is show us how few of Franklin’s countrymen appreciated that diplomatic achievement. In fact, Franklin’s diplomacy in France became the source of the suspicion that clouded Franklin’s good name in America and bedeviled the last years of his life, when some thought he had become all too close to his French friends and their interests. Isaacson, like Van Doren and Morgan and other biographers, avoids discussing the hostility Franklin had to face upon his return from France to America in 1785, especially from the Confederation Congress. Despite Franklin’s pleas, the Congress refused to do anything to provide employment for his grandson Temple and seemed to accuse Franklin of having fiddled with his accounts when he was minister in Paris. Eventually he was reduced to writing out for the Congress a list of all his services to the United States—something none of the other Founders ever had to do.

When Franklin died in 1790, few Americans outside Philadelphia mourned his passing. Although the House of Representatives adopted a moving tribute to Franklin, the Senate refused to go along. While the French fell over themselves in mourning and issued eulogy after eulogy of Franklin, the Americans did very little.

There was in fact only one eulogy for Franklin, and that was a half-hearted speech delivered by his inveterate enemy William Smith, who passed over Franklin’s obscure beginnings as too embarrassing to be emphasized. Only in the decades following the publication of Franklin’s Autobiography in 1794 did Americans come to appreciate and indeed celebrate those obscure beginnings. The Franklin we know as the archetypical middle-class American is largely an invention of the early nineteenth century.4

This Issue

December 4, 2003

-

1

Benjamin Franklin (Yale University Press, 2002).

↩ -

2

Benjamin Franklin (Viking, 1938).

↩ -

3

Isaacson has assembled a number of Franklin’s works in a companion volume to his biography: A Benjamin Franklin Reader (Simon and Schuster, 2003). These works include not only selections from Poor Richard’s Almanac and numerous newspaper pieces and bagatelles, but also Franklin’s closing speech at the Constitutional Convention, some of his letters to other Founders, and the complete Autobiography.

↩ -

4

I plan to expand on all these matters in a forthcoming study, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (Penguin, 2004).

↩