The form a city assumes as it evolves over time owes more to large-scale works of civil engineering—what we now call infrastructure—than almost any other factor save topography. The collective imagination fixes on the most conspicuous symbols of urban identity: the grand architectural set pieces of political and religious authority that predominated until the last century, when spectacular high-rise monuments to financial might reshaped skylines around the world. But without the development of complex and often ingenious systems for providing increasing numbers of city dwellers with water, sanitation, transportation, energy, and communications, our unprecedented modern megalopolises could never have emerged.

With alarming frequency lately we have witnessed a series of American infrastructural disasters, including the collapse of a highway bridge linking Minneapolis and St. Paul; the explosion of underground steam ducts in midtown Manhattan; and inundations caused by failures of antiquated water mains, weakened dams, and inadequate levees, most catastrophically in New Orleans. Advocates of a comprehensive national initiative to repair or replace aging public works have stressed how such an undertaking would spur economic recovery. But whether it does so or not, the inescapable crisis of our crumbling infrastructure must be confronted, and sooner rather than later.

Another question that arises as cities mature is what to do with outmoded infrastructure. Many architectural preservationists were slow to concede the historical merit of utilitarian landmarks until the 1960s and 1970s. An unusual reclamation project from that period looms larger in hindsight: the land-scape architect Richard Haag’s Gas Works Park of 1970–1975 in Seattle, which recycled a defunct gasification plant into a new kind of public recreation space. Haag perceived the raw beauty of the lakeside site’s abandoned mechanical components—monolithic tanks, totemic gauges, Mondrianesque pipelines—and incorporated them into his scheme as found objects. Haag’s novel idea outraged traditionalists (not least the park’s principal benefactors, who refused to have it named after them), but to others the concept seemed reasonable at a time when artists like Mark di Suvero and Alexander Liberman were appropriating I-beams and drainage culverts for their monumental outdoor sculptures.

The case for the imaginative greening of “brownfields”—derelict industrial sites, in planners’ jargon—was tremendously advanced with the opening this June of the first segment of New York City’s High Line, a linear park superimposed on the eponymous long- defunct cargo railroad trestle that wends through nearly a mile and a half of Manhattan’s West Side from midtown to Greenwich Village.

The High Line was erected some thirty feet above street level, between 1929 and 1934, by the New York Central Railroad, to speed delivery of materials and foodstuffs directly to factories and processing plants, as part of New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses’s West Side Improvement Project (three decades before he conceived of a crosstown highway that would have eviscerated Soho). Unlike the elevated trains that still clattered above the vehicular traffic of Manhattan’s Second, Third, Sixth, Ninth, and Lexington Avenues, the High Line followed a mid-block, back-door path in the Chelsea district between and through spaces behind buildings, which made the tracks virtually invisible except at crosstown intersections; and it began a veritable disappearing act in 1980 when the tracks carried their last shipment—three carloads of frozen turkeys. By the end of the century, this vestige of the city’s once-vital manufacturing economy had so faded from general memory that the High Line received not even a passing mention in The Encyclopedia of New York City, an exhaustive compendium of Gotham history and trivia edited by Kenneth T. Jackson. 1

The decade-long struggle to save the High Line from demolition and turn it into a civic amenity began in 1999, when Joshua David (then a magazine writer and editor) and Robert Hammond (a consultant for commercial and non-profit organizations) met at a local Community Board meeting, discovered their mutual enthusiasm for the moldering railroad spur, and eventually devoted themselves full-time to its salvation. As the western reaches of Chelsea attracted contemporary art galleries around Richard Gluckman’s exemplary architectural recyclings for the Dia Center for the Arts of 1987–1997 on West 22nd Street and the area became a trendy destination, the rehabilitation effort morphed into a cause célèbre among New York celebrities. Some proponents of the High Line worried that all the hype and hoopla would raise public expectations to unreasonable levels.

Indeed, at first glance the new High Line seems surprisingly modest, especially in comparison to Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s Central Park of 1857–1864, that sweeping synthesis of far-sighted urbanism, scenic wizardry, and social engineering. Nor does the High Line exude the offhanded power that gives many industrial landmarks more allure than routine start-from-scratch architecture. The trestle’s poky proportions, banal ornamentation, and recessive route delayed appreciation of it until the freight cars stopped rolling and the roadbed literally went to seed, and an abundance of weeds and shrubs flourished on it.

Advertisement

Urban archaeologists and naturalists then climbed the three-story-high viaduct and discovered a wondrous new prairie in the sky, a wild green river that flowed through concrete canyons and disappeared into the distance. The High Line’s seasonal permutations were recorded in countless photographs, none more captivating than the color images of Joel Sternfeld, which were exhibited and published in a book 2 that became a fundraising kit beyond the dreams of the canniest consultant. (See illustration on page 14.)

The redesign of the High Line was a collaboration among numerous talented specialists led by James Corner Field Operations, the landscape and urban planning office founded by Corner, chairman of the University of Pennsylvania’s landscape architecture department. 3 Some sense of the difficulties the collaborators encountered in making the High Line safe, accessible, and compliant with building codes, yet also artistically distinguished, can be gathered from Designing the High Line, a preliminary account published more than a year before the first stretch opened. We can hope for fuller documentation of an endeavor that has touched on virtually every aspect of the public planning process, a case history certain to be studied by academics and activists eager to divine its wider applicability and implications for the future.

All-star line-ups of designers have a habit of devolving into competitive chaos, but despite inevitable frictions the High Line team remained firmly committed to the project’s two fundamental principles: to retain as much of the original High Line’s gritty character as practicable, and to ensure that all new interventions reinforced the site’s distinctive qualities. By and large, the participants have succeeded admirably. The High Line marks a radical departure from the Classical model of the public park as rus in urbe —“country in city”—epitomized by London’s Hyde Park and New York’s Central Park, which allow one to imagine having been transported to an idyllic countryside. What makes walking the High Line such an intriguing experience is the way in which it celebrates rather than obviates the collision of natural and manmade environments.

The High Line is hardly the first of its kind. The most frequently cited prototype is Jacques Vergely and Philippe Mathieux’s Promenade Plantée of 1988–1993 in Paris (also known as Le Viaduc des Arts and La Coulée verte—“the green stream”), a three-mile-long masonry viaduct that extends between the Place de la Bastille and the Bois de Vincennes, with a landscaped pathway atop the structure and shops inserted into the archways below. Rotterdam is undertaking a pedestrian retrofit of its old Hofpleinlijn railway, and several other cities are making similar transformations.

On the High Line, the incongruous delight of strolling through a leafy glade three stories above the roaring traffic’s boom is made more piquant by the omnipresence of buildings crowded close to both sides of the walkway, especially at those points where it passes beneath a towering new structure and shoots straight through a cavernous old one, recalling the fanciful multilayered Manhattan imagined by illustrators for the turn-of-the-twentieth-century journal King’s Views of New York. Even if one wanted to tune out the city while communing with nature here, real estate developers and advertising agencies have made that a futile exercise.

A freakish array of exhibitionistic architecture has sprung up along the High Line, none more hideous than Jean Nouvel’s 100 Eleventh Avenue condominium tower of 2006–2009, with a curving, nervously patterned glass skin that approximates a 1950s Costa Brava tourist trap. That decade apparently also informed the Polshek Partnership’s dreadful Standard Hotel of 2006–2008, an angular concrete-and-glass slab raised atop gigantic pilotis. It straddles the High Line at West 13th Street and replicates the grim Modernism of East Berlin’s Alexanderplatz as rebuilt by Walter Ulbricht. By far the best of the lot is Frank Gehry’s IAC/InterActiveCorp Headquarters of 2003–2007, an iceberg-like mid-rise office building commissioned by the conglomerateur Barry Diller, one of the High Line’s biggest donors. And at every turn along the High Line one is confronted by panoramic billboards splashed with laughably eroticized come-ons for alcohol, cosmetics, and skimpy clothing.

The first section of the High Line begins near the meeting of Gansevoort and Washington Streets in the northwest extremity of Greenwich Village known as the Meatpacking District (many of whose wholesale butchers have been supplanted by boutiques, galleries, and restaurants). The sleek, silvery stairway ascending to the High Line at this southernmost terminus would befit the Milan Metro. Steps with deep treads perfect for Pilates devotees lead up to the promenade platform, where the centered walkway is paved with oblong concrete blocks laid end-to-end like wood-plank flooring and studded with dark-gray stones to mimic fine terrazzo.

Advertisement

Flanking the path (which varies in width along the meandering nine-block route now open, up to West 20th Street) are planting beds meant to evoke the lush, self-sown greenery that thrived on the High Line during its three decades of desuetude. To recapture some semblance of that volunteer vegetation, the project’s organizers engaged the Dutch horticulturist Piet Oudolf, best-known exponent of the wild-garden movement dubbed “New Wave Planting.” Oudolf (working with Kathryn Gustafson and Robert Israel) created the highly popular Lurie Garden of 2000–2004 at Chicago’s Millennium Park, a 2.5-acre enclave that typifies his distinctive formula of expansive, irregular drifts of softly toned, small-blossomed perennials interspersed with rippling waves of tall grasses, with strong emphasis on native species.

The windswept, painterly Oudolf approach looks spontaneous to all but experienced gardeners aware of the labor-intensive artifice needed to achieve a convincing illusion of utter naturalness. Uninitiated commentators have characterized Oudolf’s High Line plantings as “messy,” “unkempt,” and “scruffy.” Joshua David has described the atmosphere he and his co-founder envisioned as “less like a park and more like a scruffy wilderness,” but the results will appear unruly only to those who still think of public gardens as requiring Victorian carpet bedding—yellow begonias and red pelargonium geometrically composed and obsessively mulched.

Oudolf has made some knowing winks to New York City’s indigenous (or ubiquitous) plant life, including his use of sumac, a shrub with compound leaves reminiscent of Ailanthus altissima, the weedlike “tree of heaven” apostrophized in Betty Smith’s best-selling novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn of 1943 as an archetypal urban survivor accustomed to the toughest settings. (Conservationists now discourage use of that aggressively invasive species.) Conversely, some of Oudolf’s perennials are chic enough for Sissinghurst, the cultish Kentish garden made by Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson—especially a wine-dark variety of scabiosa, or pincushion flower, that bloomed on the High Line during this spring’s inaugural festivities. Nearby, Amelanchier alnifolia was in fruit at the same time, confirming one of this sturdy shrub’s common names, Juneberry. If some of Oudolf’s tree selections are dubious—white birch, for example—his plantsmanship is impressive, as are his confident juxtapositions of familiar and unusual species. Above all, his taste is impeccable yet not the least bit prissy.

Although the long, narrow confines of the High Line did not allow Oudolf to unfurl dramatic swaths of plant material as he had in the rectangular Chicago garden, he nonetheless has unified the High Line’s ribbon-like layout and given it continuity without excessive repetition. One only wishes his architectural collaborators had made it possible for visitors to sit directly among the flowers, bushes, and trees, and not just view them like pictorial dioramas. Look-but-don’t-touch is a necessary aspect of public gardens, but the High Line would be much more enjoyable if some seating had been inserted within the beds to allow close contemplation of the beautifully considered plant life.

More attention has been paid to New York’s favorite outdoor sport, people watching. In addition to clunky and uncomfortable wooden benches that seem to grow out of the wood planking, and beach-resort-like reclining lounges of the same material, there is also a dramatic cascade of bleacher seating called the Tenth Avenue Square, a glass-walled amphitheater perched above the thoroughfare at West 17th Street. Devised by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, this vertiginous vantage point is similar to the stepped computer center that the firm suspended beneath the deeply projecting cantilever of its Institute of Contemporary Art of 2002–2006 in Boston.

Some skeptics have challenged the High Line’s claims to ecological responsibility and its commitment to local, recycled, and sustainable materials. Rainforest Relief, an environmental watchdog group, has condemned the High Line’s selection of ipê, a South American wood, for the project’s extensive decking, benches, bleachers, and lounges. Noting that ipê for the most part is logged illegally, and that its commerce causes great harm to the Amazonian rainforests of Brazil and Peru, to say nothing of the region’s indigenous peoples, Rainforest Relief deems this choice both arbitrary and destructive: “While ipê is considered extremely durable,” the organization’s Web site states, “other domestic woods will last longer…. The use of ipê is mostly for aesthetics.”

Some have objected to the political and plutocratic favoritism that propelled this charmed project to completion while less glamorous park proposals for other boroughs languished. As the High Line turned into a publicity juggernaut, grandstanding officials and promotion-minded dilettantes jumped aboard. A week before global markets collapsed last September, the Calvin Klein fashion company threw an extravagant fortieth-anniversary celebration atop the High Line, replete with a temporary pavilion by the Minimalist architect John Pawson and a light sculpture by the artist James Turrell. This $3 million party would have been more stylish had most of that money gone toward the High Line’s estimated cost of $160–180 million.

Nevertheless, when the first of the High Line’s three increments finally opened, the city’s picky citizens quickly embraced it. Despite concerns about its environmental bona fides and cavils over its design details, the High Line exceeds expectations in a wholly unanticipated way. Arriving at a time of widespread impoverishment, this communal enrichment, elevated and elevating, feels like a windfall inheritance, and it has grateful New Yorkers walking on air.

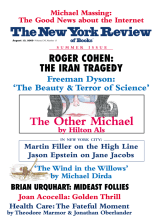

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory

-

1

Yale University Press, 1995.

↩ -

2

Joel Sternfeld, John Stilgoe, and Adam Gopnik, Walking the High Line (Steidl, 2001).

↩ -

3

Other participants included the New York architectural firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the structural engineers Buro Happold and Robert Silman Associates, the Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf, the lighting experts L’Observatoire International, and the graphics studio Pentagram Design.

↩