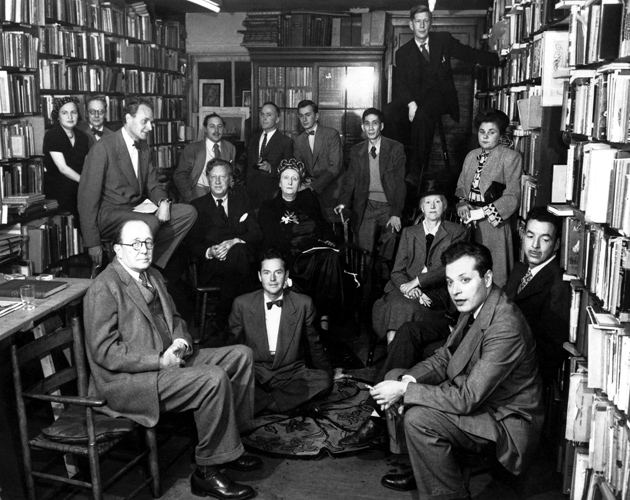

Topham/The Image Works

Attending a reception for Edith and Osbert Sitwell (seated at center) are, clockwise from top right, W.H. Auden, Elizabeth Bishop, Marianne Moore, Delmore Schwartz, Randall Jarrell, Charles Henri Ford, William Rose Benet, Stephen Spender, Marya Zaturenska, Horace Gregory, Tennessee Williams, Richard Eberhart, Gore Vidal, and Jose Garcia Villa, Gotham Book Mart, New York City, November 9, 1948

Twentieth-century American poetry has been one of the glories of modern literature. The most significant names and texts are known worldwide: T.S. Eliot, Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore, Hart Crane, Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Elizabeth Bishop (and some would include Ezra Pound). Rita Dove, a recent poet laureate (1993–1995), has decided, in her new anthology of poetry of the past century, to shift the balance, introducing more black poets and giving them significant amounts of space, in some cases more space than is given to better-known authors. These writers are included in some cases for their representative themes rather than their style. Dove is at pains to include angry outbursts as well as artistically ambitious meditations.

Multicultural inclusiveness prevails: some 175 poets are represented. No century in the evolution of poetry in English ever had 175 poets worth reading, so why are we being asked to sample so many poets of little or no lasting value? Anthologists may now be extending a too general welcome. Selectivity has been condemned as “elitism,” and a hundred flowers are invited to bloom. People who wouldn’t be able to take on the long-term commitment of a novel find a longed-for release in writing a poem. And it seems rude to denigrate the heartfelt lines of people moved to verse. It is popular to say (and it is in part true) that in literary matters tastes differ, and that every critic can be wrong. But there is a certain objectivity bestowed by the mere passage of time, and its sifting of wheat from chaff: Which of Dove’s 175 poets will have staying power, and which will seep back into the archives of sociology?

Anthologies are wonderful for the young: a single page catches fire, and a new attachment—sometimes a lifelong one—takes hold. And since space is limited, the famous poems understandably end up being the chosen ones: for Robert Hayden, “Mourning Poem for the Queen of Sunday,” “Those Winter Sundays,” “Frederick Douglass,” and “Middle Passage”; for Robert Lowell, “‘To Speak of Woe That Is in Marriage,'” “Skunk Hour,” and “For the Union Dead”; for Marianne Moore, “The Fish” and “Poetry.” Coming as a young person to this anthology, I would have loved finding such poems. But I would still have been hungry for more than the six pages here of Wallace Stevens, more than the single poem by James Merrill.

Dove not only decides for many, rather than few, poets. She also decides (except in certain obligatory moments) for the more “accessible” portions of modern lyric. Not to be “accessible” is now to be chastised. Perhaps Dove’s two years as poet laureate helped foster the impression that poetry should be written in “plain American that cats and dogs can read” (Moore, satirizing English views of America). But a poem can communicate while it is still imperfectly understood (said Coleridge), and Dove trusts her readers less than she might.

Perhaps Dove is envisaging an audience who would be put off by a complex text. So she chooses to represent Wallace Stevens by five plain-voiced poems from his first book, Harmonium (1923), and one short posthumously published poem (1957), skipping more than thirty years of Stevens’s powerfully influential writing. Did Dove feel that only these poems would be graspable by the audience she wishes to reach? Or is it that she admires Stevens less than she admires Melvin Tolson, who receives fourteen pages to Stevens’s six? Or is it that she believes that Stevens has had more than enough exposure, and that he doesn’t really need any more? If so, what are we to make of the inclusion of “The Waste Land” (shorn of notes and footnotes), the most overexposed (if also the most defining) poem of the American twentieth century? And if the aim is to present “accessible” poems, surely “The Waste Land” is anything but. Dove is willing to grant thirteen pages to John Ashbery’s long “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” which is not particularly “accessible” either. From these choices no principle of selection emerges. Dove’s brief and unsatisfactory reference to her choices goes as follows:

Although I have tried to be objective, the contents are, of course, a reflection of my sensibilities; I leave it to the reader to detect those subconscious obsessions and quirks as well as the inevitable lacunae resulting from buried antipathies and inadvertent ignorance. In anticipation of the naysayers, all I can say in my defense is: I have tried my best.

I wish Dove had directly addressed the hard questions of choice in her breezy chronological introduction, with its uneasy mix of potted history (in a nod to “context”) and peculiar judgments. She denigrates Frost’s “Design” and “Acquainted with the Night,” for instance, as “blunt and somewhat smug,” calls Eliot “a sourpuss retreating behind the weathered marble of the Church,” and says that Elizabeth Bishop “somehow managed to chisel the universe into pixilated uncertainties.” Merrill, whose “formal verse placed him squarely on the side of the poetry establishment,” is said to have shed “the jeweled carapaces of formalism in favor of the rules of the Ouija board.” Can Dove think that a poet of Merrill’s depth can be confined to the putative space of a vague “poetry establishment,” or that placing poets on one side or another of such an assumed “establishment” says anything about their abilities? And as a poet herself, she must know better than to refer metaphorically to formal verses as “jeweled carapaces”: carapaces belong, after all, to insects and tortoises. Such cartoonish remarks are not helpful to the understanding of poetry.

Advertisement

When Dove is not sympathetic to a given poet, her remarks on the poetry itself can be misleading. Her portrait of Stevens gives us a tepid and boring writer:

[Stevens] exhibited none of the anxiety modernism often engendered; rather than fret over the lack of objective reality, Stevens championed “the supreme fiction” of the mind, content to walk to work every day, write his poems, and savor “the music of what happens.”

Has she read Stevens on tragedy?

It leaps through us, through all our heavens leaps,

Extinguishing our planets, one by one,

Leaving, of where we were and looked, of whereWe knew each other and of each other thought,

A shivering residue, chilled and foregone.

Is this spoken by a man without anxiety, who does not “fret,” who is content with savoring “the music of what happens”? Or—to give another example—has Dove read Stevens on marriage, as he looks back on it in old age?

The meeting at noon at the edge of the field seems likeAn invention, an embrace between one desperate clod

And another in a fantastic consciousness,

In a queer assertion of humanity.

And sometimes one wonders whether Dove is being hasty. She speaks, for instance, of “the cacophony of urban life on Hart Crane’s bridge.” But the bridge in his “Proem” exhibits no noisy “cacophony”; its panorama is a silent one. The seagull flies over it; the madman noiselessly leaps from “the speechless caravan” into the water; its cables breathe the North Atlantic; the traffic lights condense eternity as they skim the bridge’s curve, which resembles a “sigh of stars”; the speaker watches in silence under the shadow of the pier; and the bridge vaults the sea. The automatic—and not apt—association of an urban scene with noise has generated Dove’s “cacophony.”

The simplest thing to say about Dove’s introduction is that she is writing in a genre not her own; she is a poet, not an essayist, and, uncomfortable in the essayist’s role, she strains for effects (alliteration the favorite) on the one hand and, on the other, falls into mere boilerplate. Before returning to her individual judgments, I want to look at the large outlines of her introduction, which suffers from a simplified history in which epochs have to be accorded a yes and a no, a plus here, a minus there. Treating the beginning of the twentieth century, Dove offers stereotypes and clichés as she lifts the curtain, revealing

defeated but defiant former Confederates, victorious but insecure Northerners,…freedmen struggling to create an identity,…waves of immigrants…[who] brought their own cultural riches to the mix, but also their social and economic traumata…. As the new century dawned, many citizens who could afford a little wiggle room were motivated to start afresh, do things differently, embrace the new.

How did they start? Afresh. How did they do things? Differently. What did they embrace? The new. Even our own uncertain present is evoked with platitudes: we are

bombarded…by the multifarious, conflicting verities advanced by our ever-present audiovisual media. We must remember, however, that until the advent of television, news arrived through narrow, privileged channels.

Has Dove forgotten the wide channels of newspapers, tabloids, magazines, weekly newsreels, and radio (the latter two available to the illiterate)? Well before the advent of widespread television, the Forties were full of the energetic public dissemination of news by all the mass media named above: How long did it take for the news of Pearl Harbor to spread? Or the news of the death of Roosevelt?

When we arrive at the history characterizing the Harlem Renaissance, Dove is exclusively enthusiastic:

Advertisement

A taste of economic independence, a ready-made community built upon shared experiences, songs, and sorrows—the combination was joyous, galvanizing, and irresistible…. Buoyed by racial pride,…[black artists] felt empowered to explore all aspects of their humanity, no longer locked into the roles of militant or minstrel.

The “ready-made community” was not happy to see Langston Hughes describing in print its pimps and prostitutes and faithless husbands; nor was Hughes himself happy even in this “joyous, galvanizing, and irresistible” moment. Disheartened with American racism, he hoped briefly for a better life in Russia under communism, but (still a Communist sympathizer) returned in disillusion from Russia to Harlem. Nor was Hughes able to join in any “community” with his closeted homosexual fellow writers Alain Locke and Countee Cullen. The many painful complexities of the events and personalities (black and white) of the Harlem Renaissance are lost in the cheery picture transmitted by Dove.

Her sketch of Fifties America is no less drawn to cliché, as is her idealistic vision of democratic forefathers, (slaveholders, many of them):

It’s hard to imagine what a jolt Ginsberg’s Howl gave to the self-satisfied fifties, with broadcast series like Father Knows Best crooning peace and prosperity while GIs died in Korea and McCarthyism mocked the forefathers’ democratic ideals.

As we approach Dove’s own half of the century, her judgments are no less questionable:

Every soup gets cold, however, and by the time the Beat poets were losing verbal steam, their take-no-prisoners approach had cleared a trail for the Confessionals…. The cost of [the Confessionals’] personal exposure was high. Both Sexton and Plath killed themselves…. In the end [John Berryman], too, could no longer resist the Grim Reaper.

Well, any number of people have committed suicide without being poets of “personal exposure”; and in the poets named by Dove the causes of suicide other than poetry-writing are numerous (childhood trauma, alcoholism, manic-depressive illness, marital breakdown). Dove’s brisk post hoc, propter hoc diagnosis of these heartbreaking events and their accompanying poems seems oddly imperceptive in a poet.

As for the Black Arts movement (when Dove gets to it), yes, it was a “necessary explosion,” but no, it ended badly: the erstwhile “militants and minstrels” have become “buoyantly brash” (as Dove’s alliteration takes off once again):

These buoyantly brash artists found that their public acceptance was spilling beyond their target group, with white students wearing dashikis and crooning to Marvin Gaye. Such success also encouraged other neglected voices to speak up…. On the other hand, certainly, and sadly, the willful self-segregation of the Black Arts movement contributed to a new entrenchment of a largely whitewashed poetry establishment.

We’re back to that “poetry establishment” again. The members (whoever they are) of this so-called “establishment” “entrench” themselves (as in a war) and, implicitly racist, appear “whitewashed” like the “whited sepulchres” denounced by Jesus. How is it that Dove, a Presidential Scholar in high school, a summa graduate from college, holder of a Fulbright, and herself long rewarded by recognition of all sorts, can write of American society in such rudimentary terms?

As “the melting pot was simmering,” the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War rise into Dove’s essay: “The old Euro-American literary standards were rejected, and African culture (or rather, an idealized idea of Africa)…became the rallying cry of the New Black Aesthetic.” Why should the precious and ever-rare concern for words and for their imaginative alignment be abused as “the old Euro-American literary standards”? It would have been useful if Dove had departed from her once-over-lightly historical summaries to explain the “literary standards” of “the New Black Aesthetic” as they appear in one of the poems she reprints, Amiri Baraka’s “Black Art”:

We want poems

like fists beating niggers out of Jocks

or dagger poems in the slimy bellies

of the owner-jews. Black poems to

smear on girdlemamma mulatto bitches

whose brains are red jelly stuck

between ‘lizabeth taylor’s toes. Stinking

Whores!…

Setting fire and death to

whities ass.

There is a lot of this showy violence (“cracking steel knuckles in a jewlady’s mouth,” etc.); and then Baraka, not finding any other way to close the rant, turns sentimental, in the manner of E.E. Cummings:

Let Black People understand

that they are the lovers and the sons

of lovers and warriors and sons

of warriors Are poems & poets &

all the loveliness here in the world

Dove must realize that the new “literary standards” behind this example of Baraka’s verse don’t immediately declare themselves. Printing something in short lines doesn’t make the writer a poet; it only makes him a person with a book of short lines. Nor is mere presence in the scene at a given moment enough to pronounce a person a poet. Although Dove mentions oral literature, orality has its own high standards (and we recognize them in action in everything from oral epic to Walt Whitman to black spirituals to Langston Hughes). If one wants evidence of black anger against “whitie” and “jewladies” and “mulatto bitches,” here it is. But a theme is not enough to make a poem.

Dove feels obliged to defend the black poets with hyperbole. It is legitimate to recognize the pioneering role of Gwendolyn Brooks, just as it is moving to observe her self-questioning as she reacted to the new aggressiveness in black poetry. But doesn’t it weaken Dove’s case when she says that in her first book Brooks “confirmed that black women can express themselves in poems as richly innovative as the best male poets of any race”? As richly innovative as Shakespeare? Dante? Wordsworth? A just estimate is always more convincing than an exaggerated one. And the evolution of modern black poetry does not have to be hyped to be of permanent historical and aesthetic interest. Language quails when it overreaches. The excellent contemporary poetry of Yusef Komunyakaa and Carl Phillips needs no special defense.

The school anthologists of the past, knowing their young pupils’ limits, offered many “accessible” poems, usually narrative ones, purveying simple moral instruction in patriotism or religious feeling. But it was assumed that adult readers of poetry could progress beyond “Hiawatha” or “Barbara Frietchie” to works attaining varieties of diction, overlapping intellectual structures, and complex moral reference.

Perhaps Dove’s canvas—exhibiting mostly short poems of rather restricted vocabulary—is what needs to be displayed now to a general audience. But the American scene of the past hundred years is far richer than this sample suggests. Seeing the single poem included by James Merrill, I want to turn to the reader and say, “But there’s a much better Merrill than the one who wrote ‘The Victor Dog’!” Seeing that the scanty Ammons selection ends with the 1968 “Corsons Inlet,” I want to cry out that he wrote almost thirty more years of poems, and could we please perpetuate “Easter Morning”? And it is sometimes difficult to adjust Dove’s effortful remarks in the introduction to her choices: where in Bishop’s “The Fish” or “Sestina” or “One Art” can we behold the poet “chisel the universe into pixilated uncertainties”?

Of the twenty poets born between 1954 and 1971 (closing the anthology), fifteen are from minority communities (Hispanic, Black, Native American, or Asian-American), and five are white (two men, three women). Dove’s tipping of the balance obeys a populist aesthetic voiced in the introduction. The only canonical poets she writes about with real enthusiasm are the ones using what she feels to be popular language. Of Frost: “‘The Death of the Hired Man’ takes the pith and immediacy of Shakespearean drama and places it squarely in the poetic arena”; of William Carlos Williams: “[His invention, the ‘variable foot’] found its apotheosis in Williams’s great book-length love poem, Asphodel, That Greeny Flower“; of E.E. Cummings: “Into a hothouse of exotic, overcultivated, and cross-fertilized specimens [Dove must mean Eliot, Stevens, Pound], he let in a blast of outside air.”

It seems that Dove would like to see more poets like Frost, Williams, and Cummings, and fewer like Merrill, Graham, and Ammons. Most of the new poets at the end of the book are writing in her preferred demotic style, with openings like these:

We were so poor.

The air was a quiver

of thoughts….This is my father.

See? He is young.Off go the crows from the roof.

The crows can’t hold on.Home’s the place we head for in our sleep.

But compare, to these flat invitations, the opening of Crane’s “Proem,” with its immediate energies of syntax, vocabulary, active verbs, and sound effects:

How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest

The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him,

Shedding white rings of tumult, building high

Over the chained bay waters Liberty—

Or compare the enigmatic interest of the opening of Adrienne Rich’s “Planetarium”:

A woman in the shape of a monster

a monster in the shape of a woman

the skies are full of them

One wants the contemporary poets of Dove’s collection to ask more of their language, to embody more planes of existence, to dip and pivot like the seagull. There are such poets living now, but they are either absent or in short supply in this book.

An implacable myth of progress animates Dove’s historical observations:

Toward the middle of the twentieth century, especially after World War II, the view shifted: Pound’s antiquities had lost their luster, Eliot’s England grown stale, the call of Crane’s Brooklyn Bridge faded to an echo. West of the Hudson lay a brave new world: the hardscrabble Appalachia of James Wright’s southeastern Ohio, Philip Levine’s working-class Detroit, Gwendolyn Brooks’s impoverished bean eaters in Chicago, the transcendental hermits of Robert Bly’s Minnesota winters.

Manifest Destiny as poetic conquest. This narrative of luster lost and echoes fading is simply not true of artistic succession; one might as well say that Shakespeare has faded to an echo and Faulkner has lost his luster. Crane’s tremendous vision of the Bridge has not yet dimmed. And one must, after all, face the fact that all poets who wield language powerfully are exquisitely well educated, even if they have had to educate themselves, as Whitman and Dickinson and Crane did. Just because one describes a “hardscrabble Appalachia” doesn’t make one a hardscrabble Appalachian. James Wright graduated from Kenyon, did a Ph.D. at the University of Washington, and had a Fulbright; not the usual Appalachian life. And Philip Levine, with a BA from Wayne State and an MFA from Iowa, taught for thirty years at California State at Fresno, hardly the life of a working-class person. Robert Bly went to Harvard, and presumably became acquainted, then or earlier, with some “transcendental hermits” of New England, of whom Thoreau was the most original. Hermits do not exist only in Minnesota.

Pegging poets to their origins doesn’t change the fact that they leave those origins behind and live the “elite” life of the educated, even when, like Whitman, they live in poverty. And there is nothing intrinsically poetic about being “West of the Hudson,” any more than it is intrinsically poetic to be East of the Hudson, then or now. Dove’s implication that rough diamonds in the West took over from effete Anglophiles in the East neglects the basic truth that all gifted poets are engaged in the very same task—making words come to the call of their vision.

If Dove has not succeeded in her narrative—with its strenuous attempts to be “peppy”—that is only a further sign of how difficult it is to broker poetry to the American public. There is hardly a teacher of poetry who hasn’t left her classroom wondering if she has debased the poem by trying to “put it over” to adolescents. The temptation to “jazz up” the poem is always there, and to find the line that is delicate but fervent is not easy. Yeats, in “The Fisherman,” thought a poem should be “cold/And passionate as the dawn”—that it should embody, along with the rising passion of inception, the cold inquisition of detached self-critique. It is not a goal easily attained, and it is never attained by most of the poets of any century, in any country, of any race.