Dark Passage, Nightfall, Black Friday, The Moon in the Gutter, Street of the Lost, Street of No Return: judging by titles alone, a reader might not expect much sunshine from the novels of David Goodis. But it’s not quite accurate to describe these novels as gloomy. There is gloomy, melancholy, and bleak, and then, several leagues below despondent, there is Goodis:

As matters stood, life offered very little aside from an occasional plunge into luxurious sensation, which never lasted for long and even while it happened it was accompanied by the dismal knowledge that it would soon be over.

The speaker of this line, a man named Gerald Gladden, happens to be one of Goodis’s most cheerful characters. Gladden is a career thief, and a venerated presence in The Burglar, the most stunning of the five novels collected by Robert Polito, the editor of this new edition. Unlike many of Goodis’s miserable souls, Gladden actually believes that life has meaning. The main thing to realize, says Gladden, is that

every animal, including the human being, is a criminal, and every move in life is a part of the vast process of crime…. The basic and primary moves in life amounted to nothing more than this business of taking, to take it and get away with it. A fish stole the eggs of another fish. A bird robbed another bird’s nest. Among the gorillas, the clever thief became the king of the tribe. Among men… the princes and kings and tycoons were the successful thieves, either big strong thieves or suave soft-spoken thieves who moved in from the rear. But thieves,…all thieves, and more power to them if they could get away with it.

Goodis is a crime novelist, but only in the way that Herman Melville is a nautical novelist and Cormac McCarthy is a writer of westerns. In Goodis’s novels, crime is philosophy. The name for his kind of philosophy is nihilism.

Most of his characters don’t have such a finely developed sense of honor as Gladden. The hero of a Goodis novel—and they are all but interchangeable—tends to be overwhelmed by fear and loneliness. He is hardened by prison, a bad marriage, or life on the street. (As a prostitute in The Moon in the Gutter says, “This street is no place for softies.”) He realizes, with a sudden jolt of nausea, that he is “riding through life on a fourth-class ticket,” that he’s “trapped” or “doomed” and sooner or later he’ll be “mauled and battered and crushed.” His hair is “drab,” he has “the kind of lips not made for smiling,” and, in at least two of the novels, he is “five seven and a hundred and forty-five.” He haunts neighborhoods with names like “Hellhole,” living in “the kind of room where every timepiece seemed to run slower.” Even his chairs look “sick.” The wallpaper, also, looks “sick.”

This is a writer who began his first novel, Retreat from Oblivion, published when he was twenty-one years old, with the sentence: “After a while it gets so bad that you want to stop the whole business.”

The novels in the Library of America collection, published between 1946 and 1954, were originally destined for paperback pulp racks at drugstores and supermarkets, their covers featuring pictures of buxom blondes and grim-faced toughs, trumpeting come-ons like “HIS CODE: HONOR—HIS DESTINY: EVIL.” In fact three of these five novels originated as paperbacks, and have almost never been available between hard covers before, except in limited printings by small presses. Goodis, who was born in Philadelphia in 1917, had a long apprenticeship in the pulp trade. In his twenties he wrote for magazines like True Gangster Stories, Gangland Detective Stories, and Sinister Stories under at least seven different pseudonyms, including Ray P. Shotwell and Lance Kermit. He later claimed that in the early 1940s he wrote more than five million words in five years. That comes out to ten pages a day.

During that period he assimilated several stylistic hallmarks of the genre: a parsimonious vocabulary, a disdain for needless embroidery, and a deadpan, declaratory tone. But Goodis’s language, while direct, is never flat. There is always a twist, a gesture to the perverse or the surreal. Often he accomplishes this through repetition. Here is Vanning, the paranoid hero of Nightfall:

The room was terribly empty. The door was closed. And the room was empty. It was good. And that was why it was bad. It was too good.

Occasionally Goodis manages this in a single line: “The trouble with people is they don’t understand people.” The effect is like watching a person go insane. Sometimes it seems that person may be you.

Advertisement

More often, however, it is Goodis’s hero. Though Goodis’s novels are nimbly plotted—the worst-possible thing always happens, usually at the end of a chapter, and it is always worse than you expect—it does not take long to realize that his real interests lie elsewhere. Dark Passage, for instance, begins as the story of a wrongfully convicted man:

It was a tough break. Parry was innocent. On top of that he was a decent sort of guy who never bothered people and wanted to lead a quiet life. But there was too much on the other side and on his side of it there was practically nothing. The jury decided he was guilty. The judge handed him a life sentence and he was taken to San Quentin.

Since it’s Goodis, there is already a creeping eeriness, a sense that we’re entering a world in which there is always “too much on the other side.” But otherwise it is a familiar dime novel premise. After receiving a life sentence for his wife’s murder, Vincent Parry escapes from prison in a cement truck. While hitchhiking he is picked up by a woman named Irene Janney. She brings him to her San Francisco apartment. At night, his paranoia rising, he finds a backstreet surgeon who is willing to reconstruct his face. Parry, like all noir heroes, is desperate for the chance to start again—a new face, a new life. As the doctor takes out the surgical tools, Parry says, “I’m a coward. I don’t like pain.”

“We’re all cowards,” says the surgeon. “There’s no such thing as courage. There’s only fear. A fear of getting hurt and a fear of dying. That’s why the human race has lasted so long.”

As Parry recovers from the operation at Irene’s apartment, he begins to realize that she knows exactly who he is, and has known from the second she picked him up on the side of the road—that she attended his trial, is friends with his old mistress, and appears to have an unnatural obsession with him.

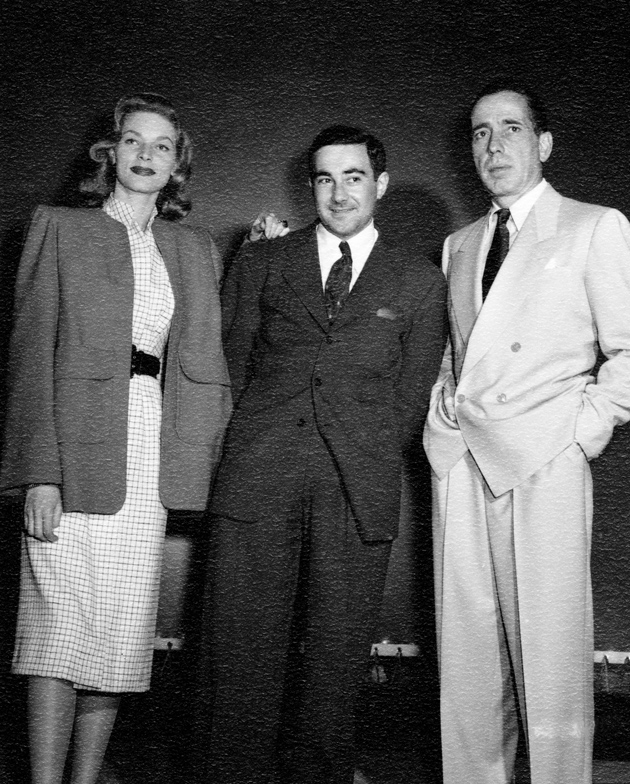

The novel was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post, then adapted into a film starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, the third of the four pictures they made together. (Goodis was hired by Warner Brothers and he moved to Los Angeles, where he stayed for six years, splitting his time between screenwriting and fiction.) Directed by Delmer Daves, Dark Passage is a claustrophobic, willfully strange film noir, with a good gimmick. The first third of the film is shot in such a way that we never see Parry’s face. When, after the surgery, the bandages finally come off, his face is revealed for the first time—and he’s Humphrey Bogart. Bacall approves.

The film is stylish and peculiar, but it does not do justice to Goodis’s astonishing portrayal of Parry’s psychological torment. And it is this, to a much greater extent than any plot twist or bit of jazzy dialogue, that gives the novel its hypnotic pull. The reader first begins to get the sense that everything is not as it seems when Irene appears in her grey Pontiac convertible: “He saw grey-violet behind the wheel. Grey-violet of a blouse belonging to a girl with blonde hair.” An unremarkable description. But then Parry notices Irene’s grey-violet skirt, grey eyes, and the large pale amethyst she wears on her ring finger. The car’s upholstery is grey velour.

They arrive at her apartment; it’s yellow brick. The corridors are “done in dark yellow.” Inside the apartment, “the general idea was grey-violet, with yellow here and there.” The walls are grey-violet. The cigarette lighter is yellow. The wastebasket is grey-violet. The radio is yellow-stained. The cabinet is yellow-stained. The ashtray is yellow, as is the phone and table. The chair is violet. The bathroom is yellow tile; the soap is lavender; the cologne is violet; the handkerchiefs are in grey-violet satin. This color scheme builds incrementally, over the course of fifteen pages, until Irene announces that she’s going to the tailor to buy Parry a new wardrobe:

“What colors do you like?”

“Grey,” he said. “Grey and violet.” He wanted to laugh. He didn’t laugh. “Sometimes a bit of yellow here and there.”

Goodis never suggests, in explicit terms, that Parry is losing his mind. But is there any question?

Parry’s sense of reality ebbs further when he visits the surgeon’s office. The doctor “freezes” Parry’s face and then goes to work with his tools:

The manipulation of steel against his face and into his face took on a rhythm that mixed with the heaviness and formed a big, heavy ball that rolled down and rolled up and took him along with it, first on the top of it, on the outside, then getting him inside, rolling him around as it went up and down on its rolling path. And he was asleep.

This is where Goodis breaks from the traditional noir formula. In hardboiled fiction, it is common that a hero begins in some version of the straight world—a penthouse society party, a suburban estate, a detective’s office—only to be pulled, inexorably, into a seedy, nocturnal criminal underworld. Goodis’s characters, on the other hand, journey inward. It is as if the surgeon’s knife, in removing Parry’s face, lays bare his hidden desires, ambitions, and terrors. The boundary between reality and nightmare dissolves.

Advertisement

It is in this semi-dream state, shortly after the surgery, that Parry pays a visit to the apartment of his one true friend, a sad loner named George Fellsinger. Parry opens the door and finds Fellsinger belly down on the floor. Fellsinger is covered with blood; his face is twisted sideways. Parry steps into the room, and addresses his best friend:

Without sound, Parry said, “Hello, George.”

Without sound, Fellsinger said, “Hello, Vince.”

“Are you dead, George?”

“Yes, I’m dead.”

“Why are you dead, George?”

“I can’t tell you, Vince. I wish I could tell you but I can’t.”

The conversation between the two men—Parry standing mute in the doorway of the blood-soaked apartment and Fellsinger dead on the ground, his head twisted backwards—continues for a full four pages.

This is not the sort of thing you will encounter in a novel by Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, or Mickey Spillane. (While in Hollywood, Goodis was assigned to write an adaptation of Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake—unsurprisingly, it was never produced.) Unlike those authors, Goodis has little interest in solving crimes and righting wrongs. His novels are more closely related to those of Jim Thompson and the romans durs of Georges Simenon, with their obsessive explorations of psychological trauma. In these novels, the problem is life, and there are no solutions.

The most striking example of Goodis’s distaste for neat endings comes in The Moon in the Gutter, the story of a stevedore’s quest to find his sister’s killer. The stevedore, Kerrigan, suspects that she was killed by a young rich alcoholic, who has recently taken to slumming in Kerrigan’s neighborhood. But soon Kerrigan meets the alcoholic’s own sister, a beautiful blonde, and he falls for her. It is, once again, a classic noir premise, with high stakes and a range of dramatic possibilities. Is the blonde seducing Kerrigan in order to protect her brother? Even if her romantic interest in Kerrigan is sincere, will she betray her brother? And will the rich blonde whisk Kerrigan away, once and for all, from Skid Row? Yet by the end of the novel Goodis renders all of these questions moot. Kerrigan realizes that the alcoholic is innocent after all, and decides that the blonde is too good for him. The murder goes unsolved. Kerrigan is left back where he started. Nothing has changed, and it is clear that nothing ever will change. He can only direct his anger at the street, the slum, the gutter. At fate, in other words.

It may come as a surprise that Goodis’s novels, despite their grimness, are rarely depressing. In part this can be credited to his skills as a pulp novelist—specifically his precise command of narrative pace and his dark sense of humor. He always seems to take a particular delight in describing quarrels between hostile lovers:

“You married me,” Madge said. “You’re still married to me. Don’t forget that.”

“How can I forget it?” Bob said. “You see these lines on my face? They’re anniversary presents.”

But the main reason for the novels’ mesmerizing power—the reason they don’t make you just want to stop the whole business—is that his characters are not genuinely cynical. Deep down each possesses a pitiful innocence that, at times, borders on idealism. His characters have learned, from past disappointments, how to harden themselves for protection—“the street is no place for softies”—but privately they nurse a secret desire to escape. (This is in marked contrast to Jim Thompson, whose prose is closer to John Wayne Gacy than James M. Cain.) Vincent Parry, for instance, fantasizes about moving to Patavilca, a beach town in Peru. In Nightfall, Vanning, another man on the run, admits in his loneliest moments that

he was missing out on the one thing he wanted above all else, a woman to love, a woman with whom he could make a home. A home. And children. He almost wept when he thought about it….

And in The Burglar, Nathaniel Harbin is determined to give his mentor’s daughter the chance at a better life, even if it means sacrificing his own.

The drama in Goodis’s fiction derives from the tension between these bursts of hopefulness and the presiding atmosphere of oppressive dread. It is believable that his heroes fantasize about Peruvian beaches or suburban homes stocked with six kids, just as it is believable when they end up, like Whitey in Street of No Return, back in the same gutter, a bottle of whiskey in hand, sinking blissfully into a mindless drunk.

Goodis himself lived a divided life. He was briefly married once, very unhappily; he never spoke of his wife again. After his six years in Los Angeles, Goodis returned to Philadelphia and moved back in with his mother and his younger brother, who suffered from schizophrenia. Goodis had a childish sense of humor. He’d stuff the red cellophane wrapper of a cigarette package into his nostril and pretend he had a bloody nose; when he went through a revolving door he’d scream loudly, as if he were being dismembered. By day he worked on his typewriter in his childhood bedroom and cared for his brother; at night he haunted billiard halls and dive bars in the seedier corners of town—Port Richmond, Southwark, and the docks, locations that appear in many of his novels. He sought out the company of large African-American women and liked to be humiliated by them.

Though he was a small man—five foot seven and a hundred and forty-five pounds—he often picked fights. In 1966, after leaving Linton’s Restaurant on North Broad Street, he was beaten by a mugger when he refused to hand over his wallet. The incident left him frail, with a chronically bloodshot eye. He dropped dead not long afterward, while shoveling snow. It was never confirmed whether his death was connected to his beating. The coroner called it a “cerebral vascular accident.” He was forty-nine.

His novels, despite being the source of numerous films, including François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player, soon fell out of circulation. Until Barry Gifford’s Black Lizard Press reissued them in the Eighties—with an introduction by Geoffrey O’Brien, now the editor in chief of Library of America—they only remained in print in France, where they were published by Gallimard’s Serie Noire imprint. This impressive new volume is an uncharacteristically cheerful coda to David Goodis’s legacy. It will allow future generations to plunge into the luxurious sensation one experiences when reading a Goodis novel, even though it never lasts for long, and is accompanied by the dismal knowledge that it will soon be over.

This Issue

June 21, 2012

Real Cool

How Texas Messes Up Textbooks

Mothers Beware!