Oliver Sacks is the scientist-as-artist, a rare species nowadays but one that flourished in the mid-nineteenth century and that almost single-handedly he has kept alive. His sensibility is Victorian in the best meaning of the word: reformist, literary, historical—empirical of course but speculative as well, in the tradition of the grand theorists of that less specialized time. As a neurologist, Sacks is a clinician above all, an unusually close listener to his patients’ symptoms and stories. He prefers to look through a wide-angle lens rather than a microscope. His impulse is to amplify his observations, to look beyond the minute workings of the brain to the varieties of human experience itself, something he has done much to map out in the medical case histories that comprise the core of his finest writing.

This isn’t to suggest that he doesn’t value the groundbreaking research of neuroscience’s current pioneers, who are in the process of adding, in steady increments, to our understanding of memory and perception, but rather that his particular mission, as I suspect he sees it, is to apply their findings philosophically, to the soul.

“Soul” may seem a strange choice of word, but reading Sacks, one senses that science for him possesses a measure of divinity. Uncle Tungsten, his memoir of his childhood until the age of fifteen, is a detailed account of falling in love with science and its “dark, hidden world of mysterious laws and phenomena.” As a young boy he was fascinated by the so-called “divine proportion,” the classical numerical formula illustrated by the Italian mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci in the early thirteenth century, that corresponds to recurring spiral patterns in nature—for example, the face of a pine cone or sunflower, or the patterns on a ram’s horn.

Sacks’s sustaining passion growing up was chemistry, but at the age of fifteen, as he tells it in Uncle Tungsten, he lost his muse. The study of modern chemistry, he discovered, was more theoretical than tactile—“a colorless, scentless mathematical world”:

This, for me, seemed an awful prospect, for I, at least, needed to smell and touch and feel, to place myself, my senses, in the middle of the perceptual world.

I had dreamed of becoming a chemist, but the chemistry that really stirred me was the lovingly detailed, naturalistic, descriptive chemistry of the nineteenth century, not the new chemistry of the quantum age.

This need to attain a level of maximum engagement with his work has seemed to hold true for Sacks as a neurologist as well. Personal revelations have marked the course of his professional life. From a very young age, he experienced migraine auras—the zigzag or fortification-like patterns and light that appear just before a migraine headache sets in. He came to regard the auras “as a sort of spontaneous experiment of nature, a window into the nervous system,” and credits them with being one of the reasons he became a neurologist.

While working at a migraine clinic in 1966, in New York, Sacks felt for the first time “a little stirring of the intellectual excitement and emotional engagement” he had felt as a boy in his homemade chemistry lab. He had been seeking a “more human approach to migraine,” something to present “the full richness of its phenomenology or the range and depth of suffering which patients might experience.”

It is typical of Sacks that he found this idea, not in any contemporary article, but in an obscure book by Edward Liveing published in 1873 entitled On Megrim, Sick-Headache, and Some Allied Disorders: A Contribution to the Pathology of Nerve-Storms:

I loved Liveing’s humanity and social sensitivity, his strong assertion that migraine was not some indulgence of the idle rich but could affect those who were poorly nourished and worked long hours in ill-ventilated factories…. What a master of clinical observation [Liveing] was. I found myself thinking, This represents the best of mid-Victorian science and medicine.

Sacks goes on to say that the book gave him

what I had been hungering for during the months that I had been seeing patients with migraine, frustrated by the thin, impoverished articles which seemed to constitute the modern “literature” on the subject.

Liveing’s writing would provide the model for Sacks’s own book on migraine, published in 1970,1 and for many of the eleven books that have followed, including Hallucinations, his latest inquiry into the varieties of human perception. Hallucinations is a compendium of the experience of hearing, seeing, smelling, or feeling objects or people that are not there. Wisely, Sacks leaves aside hallucinations that arise from schizophrenia and manic-depressive psychoses, focusing instead on those that can occur in what he calls “‘organic’ psychoses—the transient psychoses sometimes associated with delirium, epilepsy, drug use, and certain medical conditions.”

Advertisement

The differences between the two are significant. Schizophrenic hallucinations are dynamic, they speak directly to the hallucinator and he talks back to them. Their content reflects the schizophrenic’s fears and wishes; they contain, if closely listened to, traces of his emotional life. The hallucinations of organic psychoses, on the other hand, are almost always impersonal: unspooling images devoid of emotion, sometimes a nuisance, other times entertaining, always startling when they first present themselves, though, unlike the schizophrenic, the person quickly understands that they are not real.

Sacks also avoids lengthy discussion of dreams, which are, strictly speaking, a form of hallucination, since we conjure our dreams from what does not exist in the external world. The crucial difference is that dreams possess their own, self-contained narrative setting, fantastical as that may be. “We are enveloped in our dream consciousness, and there is no critical consciousness outside it,” notes Sacks. We recollect them in fragments, whereas organic hallucinations occur, and are remembered, in the vivid detail of real, waking time.

Many readers will be as surprised as I was at the number of hallucinators among us. The common thread is deprivation—the loss of eyesight, for instance, may provoke a compensating second vision, a kind of physiological nostalgia, or mourning perhaps, for what has been lost. This is called Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS), after the eighteenth-century Swiss naturalist who first observed the phenomenon in his blind grandfather. A recent study of six hundred elderly patients with visual problems in Holland

found that almost 15 percent of them had complex hallucinations—of people, animals, or scenes—and as many as 80 percent had simple hallucinations—shapes and colors, sometimes patterns, but not formed images or scenes.

Sacks puts the number of vision-impaired hallucinators at 10–20 percent. Blind in one eye, he himself has simple geometric hallucinations which, he told an interviewer, he does his best to ignore. Brain scans show that these geometric hallucinations originate lower down in the visual cortex where “a categorical dictionary of images” seems to reside—“proto-images,” as some neuroscientists call them. What is fascinating about them is their universality—they appear to exist in everyone, regardless of culture or personal history. Like the divine proportion of Fibonacci’s spiral in nature, geometric images seem to be built in to the architecture of our visual system in a pre-organized way. “Such activity operates at a basic cellular level,” Sacks writes, “far beneath the level of personal experience. The hallucinatory forms are, in this way, physiological universals of human experience.”

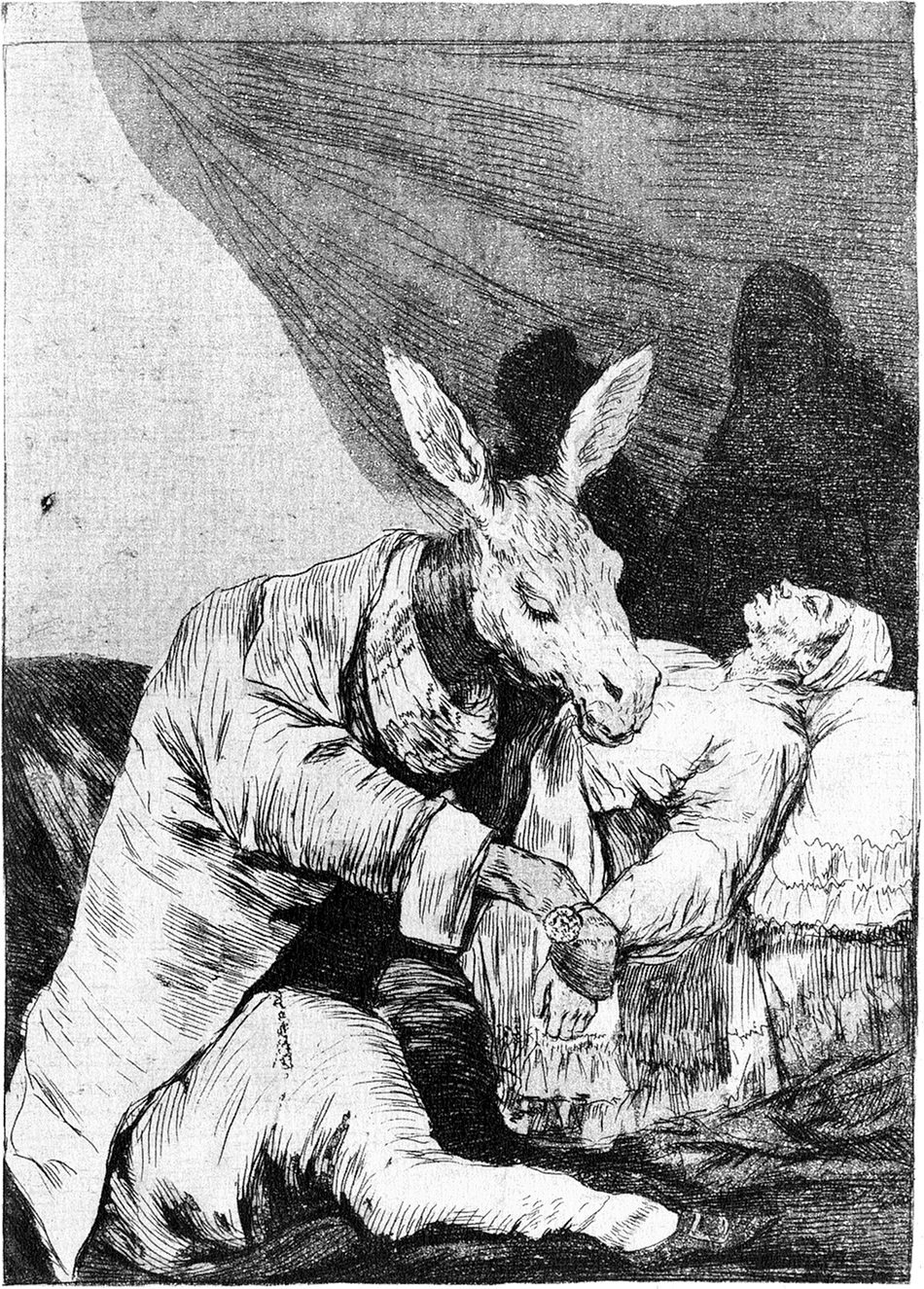

The geometric patterns in migraine hallucinations appear in nonliving things as well—“in the formation of snow crystals, in the roilings and eddies of turbulent water, in certain oscillating chemical reactions”—allowing us “to experience in ourselves not only a universal of neural functioning but a universal of nature itself.” Sacks puts forth the possibility that these universal patterns provide us with our first intimations of formal beauty, and notes the prevalence of migraine-like patterns in the art and architecture of “virtually every culture, going back tens of thousands of years”—in Islamic art, in medieval motifs, and in the bark paintings of Aboriginal artists, to give a few examples.

More complex hallucinations occur higher up in the visual system, in the temporal lobe where visual memories are retained, and the parietal lobe where much of our sensory information is integrated and absorbed. These hallucinations are less universal than geometric patterns, more specific to the hallucinator’s particular frame of reference and culture, though they are still emotionally neutral. They can be comically exotic, involving strange faces and spectacular scenes. Sacks paints a picture of elderly residents with CBS in the nursing home where he has worked. They are blindsided by an elaborate parade of people pouring through the walls, the men “disreputable, disheveled,” as one of his patients described it, the women “dolled up…[in] beautiful green hats [and] gold-trimmed furs.” Typically these hallucinations last for a few days or weeks, then disappear as mysteriously as they began, only to start up again without warning several years later. One man with CBS hallucinated a detailed replica of a Brueghel painting he had seen only once.

A source of wonder to this reader is how specialized and fragmented are the different areas of our visual system. Intricate connections between discrete regions in the visual pathway must take place for what we see to be assembled into a whole that makes perceptual—and rational—sense to us. But for people with CBS and other visual disorders no such assembling of the parts occurs. One region in the visual system will spontaneously activate while the others remain dormant. Thus, a person may find herself besieged by terrifying images of dismembered and exaggeratedly grotesque faces because of heightened, isolated activity in the superior temporal sulcus, “an area specialized for the representation of eyes, teeth, and other parts of the face.”

Advertisement

Both geometric and complex hallucinations are radically different from imagined images; they are like actual sight, visual disturbances that occur the way actual perception occurs. As far as the brain is concerned, to hallucinate is to see. Brain imaging shows that when we imagine, say, a colorful scene, the areas of the visual cortex associated with color recognition remain dormant. If we hallucinate that same scene, the color recognition areas light up.

People with normal eyesight who find themselves in situations of extreme visual monotony (such as prisoners in solitary confinement, sailors on a long voyage through an unchanging sea, long- distance truckers, and high-altitude pilots) will often, after a time, begin to hallucinate. Craving sensory input, regions of the brain become hyper-excited and spontaneously spark to action.

Sacks quotes the historian of science Michael Shermer, who has written that mushers who go for days alone with their dogs in a flat icescape

hallucinate horses, trains, UFOs, invisible airplanes, orchestras, strange animals, voices without people, and occasionally phantom people on the side of the trail or imaginary friends…. A musher named Joe Garnie became convinced that a man was riding in his sled bag, so he politely asked the man to leave, but when he didn’t move Garnie tapped him on the shoulder and insisted he depart his sled, and when the stranger refused Garnie swatted him.2

One of the more curious syndromes mentioned in Hallucinations is that of people who have gone completely blind as a result of a stroke, yet continue to believe that they can see. They confidently describe the physical appearance of strangers and will not be disabused of their belief when told how inaccurate the description is. If they bump into a piece of furniture, they’ll insist that it was moved. “Such patients may be sane and intact in all other ways,” notes Sacks. Remarkably, their hallucinations—unlike those of CBS and other perceptual disorders—are contextual; they conform to the situation the hallucinator is actually in.

The fact is, if the physical setting matches reality in some way, we will believe what the brain tells us it sees. Visual evidence is more convincing to us than that provided by the other senses, even if the other senses contradict what is put before the eye. Sacks cites an experiment conducted in 1998 by Matthew Botvinick and Jonathan Cohen where a subject’s real hand was placed out of sight under a table while a rubber hand was set before him. When both hands were stroked simultaneously, the subject believed that the rubber hand was the real hand, though intellectually he knew this not to be true. Visual evidence supersedes the tactile.

Neurologically speaking, the most revealing complex hallucinations occur during the electrical brain disturbance that heralds the onset of a frontal lobe epileptic attack. The progress of an epileptic aura as it makes its way through the brain is, to some degree, a photograph of the brain in action. A typical epileptic aura marches through the brain, stimulating one area, then another, provoking corresponding hallucinations as it progresses toward its climax: the blackout of a seizure. Strange smells may be hallucinated, followed by voices, visions, and a powerful feeling of what is sometimes called “doubled consciousness,” a feeling of being “snatched away,” as one epileptic tells it, “as if I’m in two places at once, but in neither place at all—it is a feeling of being remote.”

People who experience a feeling of ecstasy during their epileptic auras are apt to identify intensely with their seizures, regarding them as evidence of their uniqueness, their chosen status. The writer Elissa Schappell says that despite the fact that her seizures are “physically and emotionally debilitating…. They make me feel inhabited by something larger than myself. They make me special.”3 Here is her description of an aura:

I am suddenly serene…rising. There is the unseen life, the illuminated world, shimmering, flooded with more light than seems possible, rushing into my palms and the soles of my feet, the air liquid with light, so much I should be able to scoop it into my hands like water. It fills the corners of the room, runs down the walls. I am ecstatic. I don’t want it to end. Not now, not yet, just as I’m about to understand something.

Although this ecstasy—what Schappell and others have described as the proximity of the “divine”—is probably the most well-known aspect of epilepsy, according to Sacks it is relatively rare. In a wonderful passage about Prince Myshkin’s seizures in The Idiot, Dostoevsky writes of Myshkin’s anxieties calming into “a sovereign serenity made up of lighted joy, harmony and hope.” Dostoevsky told his friends that they couldn’t “imagine the happiness which we epileptics feel during the second or so before our fit…. I don’t know if this felicity lasts for seconds, hours or months, but believe me, for all the joys that life may bring, I would not exchange this one.”

It doesn’t negate the power of these experiences, or their effect on consciousness and certain important works of art, to note that virtually any part of the sensory system can be hyper- activated in a way that produces hallucinations. These hallucinations will almost always be brighter, more vivid—more sensational—than objects perceived in the actual world.

One of the rarest, and most captivating, hallucinatory experiences is synesthesia, which can happen during an epileptic aura and, most frequently, under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs.4 People on hallucinogenic drugs may experience “the smell of a low B-flat [or] the sound of green,” as a man who participated in a study of LSD at Columbia University in the 1960s put it—a variation of Baudelaire’s image, in his poem “Correspondences,” of “perfumes as cool as children’s flesh.”

This put me in mind of A.R. Luria, the renowned Russian psychologist who observed over a period of thirty years, beginning in the 1920s, Solomon Sherashevsky, a man who suffered from a rare form of memory disorder: that of being unable to forget. To his amazement, Luria was unable to measure the capacity of Sherashevsky’s memory: it was inexhaustible. Synesthesia was a constant feature of his life—he existed in what may be considered a perpetual state of hallucination. “What a crumbly, yellow voice you have,” he told one of Luria’s colleagues while conversing with him. This was typical of the sensorial confusion with which he soaked up the world. He didn’t experience the meaning of words, but rather their sound, their taste, their texture, and he assumed, with apparent good faith, that the same was true of everyone.

Numbers, for instance, were the images they evoked. 1 was “a proud well-built man,” 2 “a high-spirited woman,” 3 “a gloomy person,” 87 “a fat woman and a man twirling his moustache.” Sherashevsky recognized a particular fence by its “salty taste” and “sharp, piercing sound.” Another fence would have a different quality. Their commonality, as fences, was too vague for him to comprehend. He couldn’t categorize or forget differences or think abstractly. He had trouble recognizing people, because a face seen at three in the afternoon seemed different than that face at nine at night. Reading was a particular torment, with each sentence invoking a multiplying forest of images that made it impossible for him to follow what was going on. “Other people think as they read,” he remarked, “but I see it all.”

In his desire to forget, he would write down his memories, then burn the paper, hoping they would disappear. The most difficult word for Sherashevsky to comprehend was “nothing,” the tranquility of mental blankness. “I read it and thought it must be very profound,” he told Luria. “I thought it would be better to call nothing something…for I see this nothing and it is something…. That’s where the trouble comes in.”5

A singular species of hallucination is that of the phantom limb, not least of all because, unlike CBS and other hallucinatory syndromes, the acute and living sensation of the part of the self that is missing is felt in virtually everyone with an amputated limb. Technically, it is a hallucination because it involves the perception of something that has no material existence in the outside world. But in an important way, phantom limbs seem not to be a disorder but rather a natural neurological response to a severance and incompleteness that the body cannot accept as final or even real.

Sacks points out that “the feeling of a limb as a sensory and motor part of oneself seems to be innate, built-in, hardwired”—what Ahab, in Moby Dick, referring to his phantom leg, calls “tingling life.” This is given credence by the case of a girl born without forearms who nevertheless was able to “move” her phantom hands. As a schoolgirl she would do simple arithmetic by counting with her nonexistent fingers.6

People often have the sensation of their phantom limb in action, and this, too, is unlike other types of organic hallucinations. With the phantom, the action passes through the body and is projected outward into what is, in effect, thin air. The action is willed—the partial limb will sometimes twitch in concert with the phantom’s movements. (Admiral Nelson, who lost his right arm in battle, thought of his phantom as “direct proof for the existence of the soul.”)

The phenomenon illustrates the physical longing of our bodies to be entire and whole, and the deep inner conviction—the certainty—that this wholeness is inviolable, that it is what we are. The phantom may remain as an integral part of the body indefinitely. “A phantom foot may have a bunion, if the real one did; a phantom arm may wear a wristwatch, if the real arm did. In this sense, a phantom is more like a memory than an invention,” writes Sacks.

Over time, a phantom limb may shrink into a painfully paralyzed position. The phantom arm may disappear, while the hand remains, sprouting deformedly from the shoulder, gnarled and digging into its phantom palm with its phantom nails. In these cases the brain has abandoned the limb, because of the absence of visual confirmation of its existence. A simple and ingeni- ous remedy to this is to “show” the person the missing arm, through an optical illusion of mirrors, looking normal and attached to the hand. Upon taking in this sight, the brain will plug the hand back in and the phantom sensation will become whole and normal again.

An artificial limb, of course, is the most effective and lasting cure to the agony of phantom paralysis. Sacks writes movingly of the way an artificial limb “‘clothes’ the phantom,” giving it “an objective sensory and motor existence, so that it can often ‘feel’ and respond to minute irregularities in the ground almost as well as the original leg.” If the phantom is a lost part of the body image wishing to be reunited with its unamputated half, then a good prosthesis is the means by which the reunion can occur. For many people, the phantom disappears when the prosthesis is put on.

To get a sense of how prosthesis and phantom can merge, one need only think of last summer’s Paralympic sprinter, Richard Whitehead, who had double above-knee amputations. For Whitehead to run as he does a complete feeling of oneness must exist between the prosthesis and the rest of his body, an intentionality of movement that could not occur without the tingling phantom to guide it.

Part of the purpose of Hallucina- tions is to publicize the prevalence of organic hallucinations and, by doing so, to lessen the stigma attached to them. In medical practice, as well as in general social life, hallucinations are so firmly associated with insanity that most people who experience them remain silent—a state of affairs that has contributed to the misconception that the experience is rarer than it actually is. Many elderly deaf patients who report hearing musical hallucinations, for example, are “treated as if demented, psychotic, or imbecilic,” and put on dulling, psychotropic medication.

This chasm between actual and socially accepted experience is exactly what Sacks, with his gift for listening to his patients, is able to pick up. Throughout his long career, the transcribing of his patients’ experiences has been a kind of necessity, the truest way to comprehend and “come to terms with them emotionally.” This unique attentiveness has not only amplified our understanding of the range of human experience, it has elevated his investigations into the realm of art.

-

1

Migraine (University of California Press, 1970; revised and expanded edition, Vintage, 1999). Reviewed in these pages by W.H. Auden, “The Megrims,” June 3, 1971. ↩

-

2

See Michael Shermer, Believing the Brain (St. Martin’s, 2012). ↩

-

3

See “How the Light Gets In,” in Tin House, No. 49 (Fall 2011). ↩

-

4

Sacks devotes a chapter of Hallucinations to an account of his own extensive use of mind-altering drugs during the early 1960s. He took the drugs, he suggests, in part out of professional interest, to observe their effect on his brain, becoming, in this way, the subject of his own experiment. “My first pot experience,” he writes, “was marked by a mix of the neurological and the divine.” ↩

-

5

For a full account of Sherashevsky’s disorder, see A. R. Luria, The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book about a Vast Memory (Harvard University Press, 1987). ↩

-

6

Phantom hands are felt most strongly of all the limbs because such a large area of the brain is devoted to hand movement. ↩