I grew up in Belle Harbor, on the western part of that fragile leg of New York City’s coastland called the Rockaways, and witnessed many spectacular storms there as a boy. In September 1960, when I was six years old, Hurricane Donna inundated the streets from Jamaica Bay to the Atlantic, the entire width of the peninsula, a distance of no more than a quarter of a mile. “Bay and ocean joined,” declared our rabbi when the flooded synagogue reopened. It was the opposite of Moses’ feat of parting the Red Sea. The storm tide crested at eleven feet and during the days that followed my brothers and I floated ecstatically through the neighborhood on ruined wooden furniture that we turned into rafts.

Weeks of no school and muted adult distress followed. We fended for ourselves and waited for the water to recede. I don’t recall much official assistance beyond the exhausted sanitation workers, day after day, loading their trucks to the hilt until, by mid-November, the debris was cleared away and the only visible signs of what had happened were cracked beachfront houses and ripped jetties.

You felt close to the heavens in Rockaway (and to Idlewild Airport, as JFK was called in those days; the sight of tilting, low-flying planes was constant) and far from the rest of New York. It possessed an exposed, end-of-the-earth quality. Much of the peninsula had the abandoned aura of a rundown resort. Day-trippers from across the bay in Brooklyn, with their thrilling beach blanket intimacies and beer can picnics, traipsed in for two months a year and then abruptly departed.

The Rockaways were strictly segregated in those days, and in the most essential ways they remain so today. At the far western end of the peninsula was Breezy Point, a five-hundred-acre co-op, second only to the neighborhood of Squantum, Massachusetts, in its concentration of Irish-Americans. Then as now, it was mainly a summer community for New York firemen and police. In June 2001, The New York Times dubbed Breezy “the whitest neighborhood in the city.” When I was a boy, there was a guard in a wooden booth at the entrance to prevent outsiders from intruding. If he didn’t know you by sight, you had to explain your business, and if you had none you were sent away. Jews were restricted, a fact that we accepted as the way life was, and should be.

A mile or two to the east was Belle Harbor, twenty or so blocks of Jewish professionals and small-business owners. Our neighbor ran a dry cleaning store in Flatbush, another made jewelry boxes in a loft in SoHo. My father commuted to his scrap metal yard in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Like the Irish, we huddled protectively among ourselves. At St. Francis de Sales, the galvanizing Catholic church and school on 129th Street, the neighborhood became Irish again, larger and less exclusive than Breezy, close-knit in the deep way of certain outerborough New York communities that have managed for generations to keep their fabric from tearing. Today, it isn’t unusual to see a young couple living in a bleached wooden beach house that has been in the family for eighty years.

The Hebrew day school I attended was only a few blocks from St. Francis. Without much solemnity, we each received our parochial educations. In both schools our teachers seemed more concerned with reinforcing tribal affiliations than instilling religious devoutness. Meeting on the street, we would fight with the Irish once in a while, in a kind of obligatory harmless embrace, but mostly we ignored one another, as the grownups had taught us to do, with a mutual air of condescension and hostility. We had little understanding of one another and made it our business that it stayed that way.

At around the time of Hurricane Donna I had one Irish friend, a delicate, radiant-eyed boy of my age, with twelve siblings, all of whom addressed their parents as “Sir” or “Ma’am.” In the immediate aftermath of Donna, I admired—and envied—the way his family and their friends cared for one another, pulling their neighbors clear of ruin with an insistence that was foreign to my world where acts of mutual aid, as I saw it, were more apt to involve collecting pennies for Israel.

Further to the east were acres and acres of the extreme poor, almost all of them black, who had been removed to Rockaway from more central parts of the city, displaced by roadway construction, real estate development, and other “urban renewal” projects during the 1950s and 1960s. The black neighborhoods, known as Arverne and Edgemere, had previously consisted mainly of working-class Jews. In their excellent history of the Rockaways, Lawrence and Carol Kaplan point out that government officials regarded Jews as least likely among ethnic groups “to oppose the entry, by government decree, of blacks into their neighborhoods.”1 (Brownsville in Brooklyn had been similarly transformed from a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, as had Jewish districts in Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Detroit.) Irish and Italians, officials assumed, would fight integration, while Jews would simply move away.2

Advertisement

The Rockaway public housing projects, many between fourteen and twenty-four stories high, were isolated and self-contained, a separate, forgotten world, with some of the city’s highest rates of infant mortality, infectious diseases, and unemployment. When approaching Rockaway by car, it was jarring to see them towering over a landscape that otherwise consisted largely of one- and two-story homes. Many residents of the projects would go years at a time without leaving the peninsula. The Kaplans convincingly argue that “the Rockaway poor received worse treatment than their counterparts in any other urban location outside the south.” By the end of the 1970s, the peninsula contained half the public housing projects in Queens, though it had only .05 percent of the borough’s population. It also became a dumping ground for group homes for the mentally disabled and last-stop nursing facilities for the aged. By the 1980s, Rockaway had more of these than any other part of New York.

I made my way to Rockaway a week after Hurricane Sandy, and it was immediately clear that the entire eleven-mile peninsula had sustained a mortal, earthen wound. In Edgemere and Arverne, residents wandered the streets, dazed and broken, in mismatched boots, donated woolen overcoats, and hats with dangling ear-flaps. Some pushed what appeared to be all their belongings in shopping baskets and carts, followed by children and derelict dogs.

The usual conditions of existence had reversed: out of doors was where you now looked for what you normally found inside: hot meals, for instance, or relative dryness and warmth. The meals came from the many charities that had set up pantries in the battered lots that have been a feature of Rockaway’s blight since the city razed many of the old summer bungalows and rooming houses after World War II. Furniture lay on the street in soggy, reeking heaps—the pathetically intimate sight of defiled mattresses and stuffed chairs mixed with mounds of foam, roof shingles, Halloween decorations, and soaked, grease-streaked insulation. Groups of people waited in ankle-high puddles for buses that seemed never to arrive. Here was a drowned cat, there a pit bull with flaming eyes chained to a wrinkled Ford. “We Shoot Looters” read the sign on a house protected by a barricade of storm-mangled cars.

Families stood docilely in lines to collect basic supplies, such as baby food and candles. There were few words. A man in his forties, shivering in wet shoes, his lips chapped to the point of bleeding, told me, “I got a comforter, a blanket. It’s all good.” He lived in the Edgemere projects and was wandering the streets, gathering what he could, first for himself, then for the “shutaways” who lived in his building.

An odor had crept into the air, working its way under the tongue, taking on the quality of something chewed on and swallowed. A breeze from the sea would disperse it for a while, but soon it would return: the wet sheetrock breath of the houses, the sump pumps weakly dribbling water from their basements, sewage, and decomposing food. What was worse, however, was the sandmud, as I thought of it, that lay on the Rockaways like a foreign skin. People shoveled and raked the stuff, building gray viscid piles on the street. It drained the spirit of those trying to clear it away, partly because it had such a revoltingly permanent quality, heavy and thick.

A resident told me it was the result of “the sonic swell” that the storm had blasted onto the land. He and others spoke primarily of the sound of the storm, describing it as unlike anything they had ever heard. Another resident recalled the “powerful sucking sound” when Sandy landed, “like being swept into a tube.” William Faulkner, in his novella Old Man, about the Mississippi River flood of 1927, writes of the water’s “subaquean rumble which sounded like a subway train passing far beneath the street and which inferred a terrific and secret speed”—the sound, in Faulkner’s words, of “monstrously disturbed water.”

During the critical days immediately following the storm, with Rockaway’s subway tracks washed away, gas shortages impeding road access, and the government disaster relief agencies still scrambling to find their footing, the main help came from local volunteers. FEMA, by its nature, is a medium-term emergency assistance unit. The task of delivering ambulances, supplies, and warming tents to a disaster area, as well as thousands of agents to interview victims and assess their needs, does not lend itself to immediate action. As late as two weeks after the storm, FEMA was referring sick residents to a ramshackle storefront on 113th Street where medical volunteers had set up a makeshift clinic. And members of the Red Cross were asking grassroots volunteers, working out of battered shacks and privately donated tents, how best to distribute food. The volunteers had become, a professional relief worker admiringly told me, “the main act.”

Advertisement

It would be impossible to quantify how much suffering the volunteers alleviated. Two and three days after the storm, battalions of them began arriving from Brooklyn and elsewhere, corralled by a small network of Rockaway residents who instinctively understood what the disaster required. Some had been participants in last year’s Occupy Wall Street protest; others had “discovered” Rockaway during the past few summers, forming an attachment to the place, which, owing to its improvised, lost-in-time quality, had taken on a kind of vintage appeal.

Part of the allure was the equalizing effect of the disaster, the connections between people it provoked where economic and class resentments momentarily seemed to melt away. During the first blinding rush of need it was easy to believe that Nature was the common enemy, not poverty or bankrupt schools or crime. A few days after the storm, a graduate student from Columbia told me that she had spent eight hours with a volunteer work crew tearing out sheetrock and insulation from the basements of an entire row of one-family houses on Beach 108th Street. She was coughing and feverish, but seemed exhilarated by the hard survivalist labor. “No one knew my name,” she said. “We worked till dark and then quit because we were living by sunlight. National Guardsmen in Humvees would honk and wave at us as they drove by.” The National Guardsmen were there to carry away thousands of patients from nursing and adult health care centers whom the city had neglected to evacuate before the storm.

At his surf club on 87th Street, Brandon d’Leo, a sculptor who had worked in a studio nearby, had organized the most effective volunteer center I saw in the Rockaways. There was, despite everything, a certain majesty to Hurricane Sandy, and it appeared to have unleashed in d’Leo an almost religious energy. Some of the energy, he implied, was the after-effect of fear. When the storm hit the coast, he felt sure he was going to die. When I met him he was in a state of crisis arousal, searching for a way to make sense of what had happened. His eyes were sunken from lack of sleep and from his woolen cap sprouted a tangle of copper- and ink-colored hair. With his partner, Davina, he had supervised the canvassing of a fifty-block area, ascertaining people’s specific conditions and needs. The information was carefully recorded on various-sized scraps of paper. (Representatives from the Global Health Initiative, Doctors Without Borders, Occupy Sandy, and other organizations would later make use of his “data.”)

Donations were pouring in and it was remarkable to watch d’Leo, ten days after the storm, dispatching more than five hundred volunteers to the homes of the afflicted with supplies, shovels, and detailed instructions. He knew what was in high demand (size-five diapers) and what wasn’t (used clothes). “People dump their sorriest crap on you. They clean out their closets and tell themselves they’re doing a good deed. I was raised on welfare. You can’t throw these rags at people in distress.”

D’Leo and Davina were living in a state of deprivation themselves. The beachfront apartment they rented was badly damaged. His sculpture, which used carefully balanced steel assemblages, and his “shop” and all the work in it had been destroyed. Although he was diligently helping people to register with FEMA so they would be eligible for financial assistance, he had yet to enter his own name into the system.

Three weeks after the storm, he did finally register and was given a voucher to stay in a Bronx hotel for fourteen days. He called the hotel but they had no vacancies, “though I wouldn’t have gone there if they’d had one.” When I spoke to him shortly after this, he seemed on the edge of an abyss. “We’ve lost our minds. We’ve had our breakdowns,” he said. He wasn’t sure how he and Davina would survive the winter.

Yet they continued to run their relief effort as if it were the only thing that concerned them. Their current struggle was to recruit volunteer electricians and obtain hot water heaters and boilers for their neighbors. In the time I spent at the surf club, I saw only one storm victim sent away empty-handed: a woman seeking hair dye and perfume.

Amid the general chaos rumors were flying. One rumor had it that the city and real estate developers would use the disaster as a pretext to bulldoze single-family homes and turn Rockaway into a luxury resort. Another rumor alleged that FEMA was planning to establish a refugee camp at Floyd Bennett Field, the former municipal airport and naval air station on Rockaway inlet (it is now a park). “Once people are moved there they’ll become officially homeless,” a young resident told me. “They’ll be relocated. Their homes will be razed, just like what happened in New Orleans after Katrina.”

Though there was no evidence to support the rumors, the lack of reliable information about the fate of the Rockaways allowed them to take on a multiplying life of their own. Nothing seemed implausible. As of November 13, the electrical systems of 29,000 homes—a huge percentage of the housing stock on a peninsula whose total population was 130,000—were in danger of being deemed beyond repair. By the end of November many of those homes had their power restored, but that was no guarantee they would not be condemned. Even with electricity restored, the return of basic amenities remained in doubt. Tens of thousands of boilers and hot water heaters had been destroyed. Mold had set in and hundreds of buildings had suffered structural damage. The cost of renovation, in many cases, would be greater than the value of the houses.

Moreover, the Long Island Power Authority, which serviced the Rockaways, was in a state of collapse, beset by incompetence, subpar power maps, and customer outrage. Governor Andrew Cuomo did little to assuage local fears when he announced, “There are some people who are not going to get their power back because it is not a power issue any longer, it is a housing issue.”

In any event, the pressing question facing planners was less that of real estate development than of the future protection and habitability of the city’s coastline. Geologically, Breezy Point is no more than 150 years old; it was created by a sand drift in the late nineteenth century. How would the most fragile parts of the city endure rising sea levels and increasingly destructive tropical storms? “Defend and Retreat” is a slogan one hears often when planners speak of the threat of rising water.

Currently, every manner of solution is under discussion: movable sea walls, mammoth sand dunes, wetland edges, artificial islands capable of cushioning storm surges, densely clustered “barrier” buildings, just to name a few. Huge flood projects will surely have a major, and necessary, part in New York’s future. One can be equally sure that, in the coming years, the social and physical fabric of the Rockaways and other coastal areas will radically change. Edward Thomas, a former FEMA official, has predicted that flood insurance, which is usually provided by the federal government, will soon be mandatory for home owners and will triple in cost. Stricter and more expensive building regulations will most likely bar middle- and lower-middle-income people from living on the coast. Ronald Schiffman, a former member of the New York City Planning Commission, foresees “a massive displacement of low-income families from their historic communities.”

Officials have not made clear yet how, or if, the Rockaways will be rebuilt. Robert LiMandri, New York’s Buildings Department commissioner, told The New York Times he did not believe any “multiunit apartment buildings” would be demolished. This suggests that even if the peninsula is left to the weather, the housing projects and their inhabitants will remain.

Twelve days after the storm, I traveled to the western end of the peninsula, near Breezy Point, where the damage appeared to have a different cast. The lawns and flower beds and houses and trees were clad in a ghostly substance that resembled volcanic ash. Rockaway Beach Boulevard, the charming, two-lane street that runs through much of the peninsula, was rumbling with armored Humvees, camouflaged transport trucks, Red Cross disaster relief vans, construction vehicles of every shape and size, garbage and fire trucks, police cars, ambulances—a ragtag convoy that scattered sandmud through the air like swarming mites.

Entire blocks had burned to nothing from fires ignited by soaked electrical boxes and tipped-over candles. With water rising to seven feet in the streets, firefighters had been unable to get in. The buildings were so crumbled that what was left of their bricks looked like charred biscuits that had been gnawed at and tossed to the ground. Three Sikhs stood in front of the wreckage ladling homemade soup. Evangelical philanthropists from a Filipino church in Queens distributed care bags amid blaring hymns. A neighborhood girl held a tinfoil-wrapped sandwich aloft hoping some hungry rescue worker would accept it. A group of nine- or ten-year-old boys played touch football, wearing masks. It gave me a pang to see my former synagogue sealed shut and deserted, while a few blocks away the church of St. Francis de Sales was teeming with relief workers.

My former block, 147th Street, had the alien familiarity that “home” sometimes takes on in a dream: a place you know intimately yet have never seen. The house I grew up in bore the unfortunate Department of Buildings sticker “Restricted Use,” which marked it, for the time being, as unfit for habitation. The other houses on the street bore the same scarlet sign. Small bulldozers raced about, digging out the sandmud, like miniature cars in an amusement park. The stone beach wall that had withstood every hurricane for the past seventy-odd years had been toppled with such violence that slabs of it had cut through the sidewalk. What was left of the wooden jetties looked like crooked rows of molars peeking out from the surf. To the east, the boardwalk, which had been rebuilt a few years ago, was gone. Only the cement mooring remained, gouged and snapped off in places like vandalized statues. On the beach mechanical excavators ponderously picked out street lamps and uprooted poles.

I continued west, to Breezy Point, which was enveloped in a smoldering pall. More than a hundred houses there had burned during the storm. At the entrance, a guard stopped me. “Residents only,” he said, just as when I was a boy. I penetrated Breezy once during the fifteen years I lived nearby, when my only Irish friend brought me to his house. His father decreed that we should test ourselves in the boxing ring in the basement. The gloves were too large for our hands and had to be held in place by an extra length of string, which cut off our circulation. When his father shouted “Go!” the boy punched me hard enough to make my head ring. A few seconds later, I caught him square in the mouth, after which we fell into a clench, our hearts pounding, unwilling to go on.

I turned back around and wandered into Jacob Riis Park, a minimalist Robert Moses gem of the 1930s, where my father played handball on summer mornings while I set out beach chairs and umbrellas for day-trippers from Brooklyn. Growing mountains of debris from all over the peninsula filled the vast parking lot. Eventually the debris would be tugged to Albany on barges. From there it would be trucked to the Seneca Meadows landfill in Waterloo, New York, where a significant portion of the Rockaways will be laid to rest.

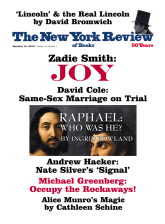

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

How He Got It Right

-

1

See Between Ocean and City: The Transformation of Rockaway, New York (Columbia University Press, 2003). ↩

-

2

In 1971, when Jewish residents of Forest Hills protested the construction of twenty-four-story housing projects in their neighborhood, the building of large-scale housing projects in New York effectively ended. See Jonathan Mahler, “How the Coastline Became a Place to Put the Poor,” The New York Times, December 3, 2012. ↩