Luís Hossaka/Museum of Art of São Paulo Collection

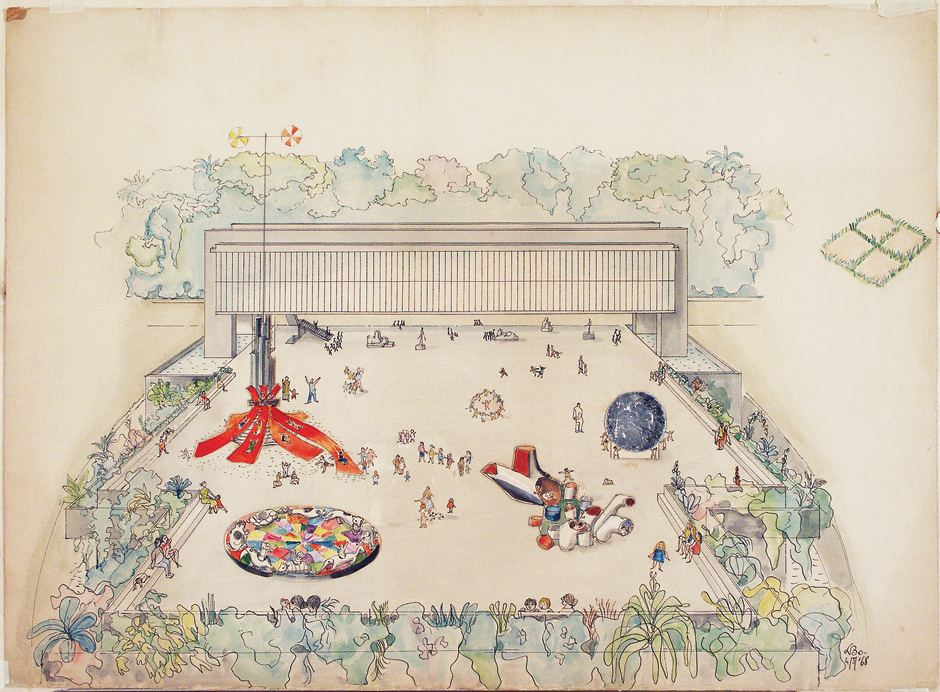

Lina Bo Bardi: Preliminary Study for Sculptures-cum-Stage-Props on Trianon Terrace, Museum of Art of São Paulo, 1965. Martin Filler writes that the masp building, visible in the background of this drawing, is a ‘feat of engineering, with just two gigantic red-painted steel trusses that span and support the two-story glass-walled gallery container longitudinally.’

1.

The hundredth anniversary of an overlooked creative innovator sometimes coincides with the revival of a reputation that is already underway. That has been happening lately with the posthumous lionization of the Italian-Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi, who was born in Rome in 1914 and died in 1992 in her adopted South American homeland at the age of seventy-seven.

Bo Bardi’s two most important realized schemes are in São Paulo—the Museum of Art (1957–1969) and the SESC Pompeia Leisure Center (1977–1986). They are of such exceptional quality that one can readily understand why their designer has at last been accorded a high place in the male-dominated canon. Intriguingly contradictory but intelligently resolved, her designs are structurally audacious yet uncommonly comfortable, unapologetically untidy yet conceptually rigorous, and confidently dynamic yet suggestively hybrid.

Although her work stands squarely in the Modernist tradition, she rejected the aggressively machinelike aesthetic favored by many of her male contemporaries, and favored a more relaxed and nuanced vernacular approach. However, as her ingenious recycling of a disused factory into the Pompeia complex demonstrates, she could also embrace industrialism’s authentic manifestations and make them invitingly human. This is high-tech that understands everyday needs and uses modern technical advances to serve them.

Some commentators have interpreted Bo Bardi’s newfound popularity as a reaction against the all-pervasive commercialism, rampant celebrity-mongering, and dispiriting lack of social awareness in architecture today. She seems to speak directly to the psychic tensions of our time, as when the architect Kazuyo Sejima of the Japanese firm SANAA, the director of the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale, organized a concise Bo Bardi retrospective as the centerpiece of that prestigious international exhibition. Many viewers felt that these decades-old designs easily outclassed the sprawling show’s surfeit of eye-catching but shallow contemporary offerings.

Typical of the esteem Bo Bardi now commands is her inclusion in Jean-Louis Cohen’s authoritative survey The Future of Architecture Since 1889,1 which features a full-page color illustration of Pompeia. She figures prominently in the introduction to Kathleen James-Chakraborty’s new general text Architecture Since 1400,2 which includes two photos of Bo Bardi’s own residence, the Glass House of 1950–1951 in São Paulo. And in Why We Build: Power and Desire in Architecture, the British architecture critic Rowan Moore devotes an entire chapter to Bo Bardi, whom he calls “the most underrated architect of the twentieth century.”3

A major event in this long-overdue recognition is Lina Bo Bardi, the first full-length life-and-works, by Zeuler R.M. de A. Lima, an architect and professor at Washington University in St. Louis. His detailed but well-paced monograph is a feat of primary-source scholarship and thoughtful analysis. Lima does a masterful job of candidly assessing his brilliant, somewhat erratic, and not always truthful subject. This important contribution to the literature will long remain the essential Bo Bardi publication.

Complementing it is Cathrine Veikos’s Lina Bo Bardi: The Theory of Architectural Practice, the first English translation of Propaedeutic Contribution to the Teaching of Architecture Theory (1957), Bo Bardi’s fullest exposition of a design philosophy. (The title’s obscure first word means a preliminary introduction to further study.) Bo Bardi’s heavily illustrated and footnoted text—similar in format to Robert Venturi’s more famous Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966)—reveals her deep grounding in the Classical tradition, a product of her interwar Roman architectural education.

Also like Venturi, she extracts applicable contemporary lessons from historical prototypes rather than mining them for directly replicable motifs. Her analogies are most forcefully advanced through provocative juxtapositions of images. She finds Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in New York a modern counterpart of the Platonically perfect proportions Raphael devised for his Church of Sant’Eligio degli Orefici in Rome. And in pairing a high-rise fantasy project by the Renaissance architect Filarete with a photo of Cass Gilbert’s Woolworth Building in New York she wonders, “Was [Filarete] anticipating the skyscraper?,” then answers her own question by asserting that “in the history of men of genius can be found the germs of all anticipations.”

Throughout, Bo Bardi’s sardonic wit and argumentative personality repeatedly surface, imparting a worldly-wise tone that makes her book anything but a dry educational treatise. In a profession where personal appearance and public presentation matter a great deal, Bo Bardi (as her photographs show) might be seen as the Anna Magnani of architecture—an earthy, passionate, careworn, impulsively outspoken character fed up with the hypocrisy of polite society. One perceptive friend, the publisher and playwright Valentino Bompiani, dubbed her la dea stanca (the tired goddess). A defiant outsider sensibility emerges from the architect’s prickly but heartfelt pronouncements on the role of architecture in modern society.

Advertisement

Also clear is her belief that design pedagogy ought to discourage what she called “the complex of the individualistic architect”—not as a means of stifling personal creativity but “to create a collective consciousness of architecture in schools, the opposite of an arrogant individualism.” Yet even Bo Bardi at her most cynical could not have imagined today’s worldwide epidemic of freakishly exhibitionistic construction, marketed as advanced artistic vision but devoid of the most basic concern for communal life and environmental impact.

On the other hand, she stubbornly refused to recant her Communist affiliations, even after the horrors of the Gulag had been revealed, and like many pioneering women in her profession she believed more in personal advancement than in solidarity in sisterhood. Thus, in a 1989 lecture, she could deliver the pugnacious pronouncement that “I am Stalinist and anti-feminist.” In fact, as we shall see, her vision of architecture and her actual work were anything but Stalinist.

Stones Against Diamonds, a collection of Bo Bardi’s writings, was recently issued by London’s Architectural Association, part of its commendable Architecture Words series. In addition to twenty-two articles she wrote in Italy and Brazil, it includes the transcript of her last lecture, in which she acknowledges her considerable debt to the British scholar Geoffrey Scott’s seminal book The Architecture of Humanism: A Study in the History of Taste (1914). Her invocation of this now somewhat unfashionable text is typical of her contrarian but principled nature. Two years from now she will figure prominently in a Museum of Modern Art survey of Latin American architecture from 1955 to 1985, curated by Barry Bergdoll. And in 2016 she will be at last accorded that ultimate establishment accolade, a MoMA retrospective of her own.

Why Bo Bardi had been denied her rightful prominence for so long is not difficult to explain. Ingrained prejudice against women in the building art prevailed throughout most of the twentieth century and still has not been fully eradicated. Even the best-remembered female Modernist architects who came of professional age during the decade after World War I and just before Bo Bardi—Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Lilly Reich, and Charlotte Perriand—were customarily assigned interior design tasks by architectural offices headed and largely staffed by men.

This enforced male/female division of labor remained the norm until the end of World War II, when women finally became principals in architectural firms, though were not always acknowledged as such. (Natalie de Blois, a former Skidmore, Owings & Merrill partner who died last year at ninety-two, was responsible for several buildings routinely attributed to the firm’s senior designer, Gordon Bunshaft, but she was often excluded from client presentations and group photos because of her gender.) The few postwar women architects who did receive rightful recognition tended to work in partnership with their husbands, including the British team of Alison and Peter Smithson and the American couple Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi.

2.

Achillina di Enrico Bo was born four months after the outbreak of World War I to a family who lived in a working-class neighborhood near the Vatican. From an early age Lina, as she was known, harbored extraordinary, not to say grandiose, ambitions. “I never wanted to be young,” she later recalled. “What I really wanted was to have a history. At the age of twenty-five, I wanted to write my memoirs, but I didn’t have the material.”

Like many other women who went on to achieve success in male-dominated professions, she identified with her father, a small-time building contractor with artistic yearnings. (An amateur painter, he befriended Giorgio de Chirico, who did a portrait of the young Lina.) She displayed unusual skill at drawing, and in 1930 entered the Liceo Artistico di Roma. Upon receiving her degree four years later she enrolled at the Rome School of Architecture, where two professors had a decisive impact on her architectural thinking.

The historian and urban planner Gustavo Giovannoni was a strong advocate of ambientismo (contextualism)—designing buildings to fit in with their immediate surroundings in scale and material—as well as a staunch preservationist. Marcello Piacentini, president of the National Fascist Union of Architects, undertook huge Stripped Classical commissions for the Mussolini regime that included a new campus for the University of Rome and the city’s EUR district (planned for the subsequently aborted 1942 World’s Fair). Especially strong was Piacentini’s emphasis on being an architetto totale—a complete architect, equally conversant with new construction, restoration of old buildings, and city planning (a range Bo Bardi extended to include the design of interiors, furniture, and jewelry).

Advertisement

She received her degree in 1939, and then moved to Milan, where the progressive design scene was much more drawn to the rationalist ideas of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier. Two months after her arrival, Italy entered World War II, a time “when nothing was built, only destroyed,” as she put it. Bo supported herself during the conflict with graphic design and illustration jobs, especially for Lo Stile, a design magazine spun off by the architect and industrial designer Gio Ponti from his influential journal Domus.

In 1946 she married Pietro Maria Bardi, a journalist and art dealer fourteen years her senior, who had cultivated strong ties to Mussolini. As Lima points out, there is no evidence to support her claim that she had worked with the anti-Fascist resistance, and although she aligned herself with the Communist Party after 1943, her close association with Ponti—whose early support for the Fascists has been rationalized by apologists as more patriotic than ideological—impelled the newly married couple to quit Italy when the Communists gained ascendance in the first postwar elections.

Pietro Bardi already had connections in Brazil, where he had traveled in 1934 to sell art to prosperous Italian expatriates. With his prospects in Italy at low ebb, friends in Rome’s Brazilian embassy set up a series of commercial exhibitions for him in Rio, where he attracted the attention of the culturally ambitious press magnate Assis Chateaubriand (known as Chatô), who wanted to foster a Brazilian arts scene commensurate with the country’s increasing international identity as a major center of modern architecture signaled by “Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old, 1652–1942,” a popular exhibition held at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1943.

Bo Bardi, who had yet to build anything, received a chilly reception from two leaders of the country’s architectural avant garde. Lucio Costa told her, “You’re so dull, so many drawings,” while his colleague Oscar Niemeyer averred that “Europeans make things seem too complicated.” Yet she contradicted both those competitive putdowns with her first completed work, the Casa de Vidro (Glass House), the sublimely simple yet uncommonly elegant residence she created for herself and her husband in São Paulo.

Not the least interesting aspect of this rectangular Minimalist structure with transparent peripheral walls is its close relation to two more renowned contemporaneous domestic designs: Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House of 1945–1951 in Plano, Illinois, and Philip Johnson’s Glass House of 1949–1950 in New Canaan, Connecticut. Yet the considerable differences among this trio of glass houses tell us a great deal about why Bo Bardi has gained such an ardent following in recent years.

The much-vaunted intention of Mies’s and Johnson’s inhabitable glass walls was to make interiors at one with nature. Johnson referred to the sylvan views from his Glass House as “the world’s most expensive wallpaper,” but as often happened with this self-critical nihilist, his wisecrack contained a kernel of harsh truth. Both his and Mies’s shoebox-shaped structures present themselves as industrially made objects, but they were in fact exquisitely custom-crafted villas for the rich.

The Casa de Vidro is a glass-walled rectangle much like the Mies and Johnson houses (and likewise more or less flat-topped, though the roof of the Brazilian version inclines slightly downward from a center ridge for rain run-off). However, it differs from them in being sited on a steep hillside, to say nothing of being considerably more economical than its expensively detailed American analogs. And the underlying concrete slab of the São Paulo residence is elevated on a series of tall, thin aluminum poles, with the structure fully touching the earth only at the uppermost, rear portion of the slope.

This was the first house to be erected in a newly developed residential neighborhood, and completion photos depict a rather barren setting reminiscent of the Hollywood Hills. Indeed, Bo Bardi’s lightweight, open-to-the-outdoors design, framed in thin members of white-painted metal, brings to mind the experimental Case Study Houses of the late 1940s and early 1950s in Southern California. Yet just a few years after its construction, the Casa de Vidro was engulfed in a lush tangle of greenery, and it now feels like a subtropical tree house.

3.

Bo Bardi’s populist outlook was antithetical to the grandiose vision realized in the Brazilian heartland by Costa and Niemeyer—the former’s urban plan and the latter’s principal structures for Brasília, the start-from-scratch capital city decreed by President Juscelino Kubitschek in 1956 and essentially completed within his five-year term of office. Whereas Bo Bardi was immediately taken by her new country’s folkloric traditions and multiracial vernacular culture, her best-known coprofessionals there were much more concerned with how to recast Baroque monumentality in High Modernist terms.

The planners of Brasília paid scant attention to the housing and transportation needs of the sizable labor force needed to serve the capital city’s bureaucracy. These omissions resulted in a host of messy ad hoc stopgaps by local residents to correct Costa and Niemeyer’s functional lapses. Bo Bardi was one of the few contemporary critics of these architectural stars, and certainly the most insightful. In 1958, just as construction of Brasília was getting underway, she wrote “Architecture or Architecture”—a short, sharp warning about the disturbing direction Niemeyer’s schemes were taking, away from his smaller early works (today his most admired designs) and toward the megalomaniacal scale typified by the new city’s flying saucer–like parliament building:

More than the buildings of Brasília—which, according to Niemeyer himself, are irreproachable in their conception and purity—we like the church in Pampulha and the house in Vassouras, which have attracted international attention on account of their simplicity, their human proportions, the modest and poetic expression of a life that rejects that very despondency, that struggle between social needs and architecture—the struggle that Niemeyer claims to have overcome by setting out, as the aim of his architecture, a formal position that denies all human values….

In contrast, Bo Bardi found ways to combine the large dimensions appropriate to the public sphere with an intimate scale that gives the users of her buildings a greater sense of both individual presence and group connection than Niemeyer was generally able to achieve in his works from Brasília onward, when colossal geometric formalism became his overriding principle. This unlikely, but in her hands fully integrated, balance was achieved with striking imagination in the Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP), an institution founded in 1947 by Chatô, directed by Pietro Bardi, and during its first decade housed in temporary spaces designed by his wife within existing structures.

Among the Bardis’ beliefs was that pictures ought not to be hung on a wall like bourgeois decorative elements but instead displayed on freestanding easels that give a closer idea of the works’ means of production. Thanks to Chatô’s strong-arm acquisition tactics—the unscrupulous publisher, who has been called the Brazilian Citizen Kane, blackmailed prominent figures with threats of newspaper exposés in return for donations to his new museum—Bardi was able to quickly assemble what at that time was the most important public art collection in South America with works, for example, by Manet, Cézanne, and Van Gogh.

MASP offered a revolutionary rethinking of the art museum, and was the embodiment of the Bardis’ belief in architecture as a prime agent for social cohesion. Their innovative ideas about the museum as an educational institution responsive to the public and not just a repository of precious objects were reflected in her equally inventive design solutions for welcoming entry areas, flexible exhibition spaces, and a casual atmosphere that emphasized art as a pleasure for everyone, not just an informed elite.

To be sure, Edward Durell Stone and Philip L. Goodwin’s Museum of Modern Art of 1936–1939 in New York had already made a notable departure from the formality and monumentality of traditional Beaux-Arts gallery design and toward a relaxed domestic scale that reminded twentieth-century New Yorkers more of their apartments than of princely palaces. But MASP took such democratic notions even further, though its architectonic presence was anything but recessive.

In an unexecuted 1952 scheme for a museum at the seashore (illustrated on the cover of Habitat, the influential art-and-design magazine the Bardis founded), Bo Bardi devised an elongated shoebox form that would have been hoisted one story above the ground by four inverted, squared-off U-shaped trusses of red painted steel clamped across the gallery enclosure’s narrower dimension. In a further refinement of that unusual format, MASP is an even bolder feat of engineering, with just two gigantic red-painted steel trusses that span and support the two-story glass-walled gallery container longitudinally rather than laterally.

This configuration provides two urbanistic benefits: it elevates the museum above the busy vehicular traffic streets that flank the building to the north and south, and the underside of the superstructure creates a roof for the open-sided gathering place at ground level. The large outdoor space, protected from sudden tropical downpours, is used for public events of all sorts, and remains one of São Paulo’s most memorable modern civic gathering places.

The open-plan exhibition areas suspended above this plaza were conceived to be optimally adaptable for various kinds of art, with interchangeable partitions and freestanding display elements. Curators were thereby encouraged to rethink visitors’ progression through exhibitions, which in conventional institutions allows little or no deviation from a strictly imposed route. The wide-ranging possibilities here gave an entirely different character to the art-viewing experience, and the MASP approach is now standard practice at contemporary art institutions, because the unpredictable display requirements for today’s large installation pieces, video art, and other nontraditional mediums have made such easily transformable interiors mandatory.

Although the ground-level public space of MASP functions wonderfully as a social magnet, it is surpassed in that respect by Bo Bardi’s final major work, the SESC Pompeia Leisure Center. Many early modernists, most conspicuously Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius, admired the no-nonsense functionalist aesthetic of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century industrial structures. In homage, they designed schools, cultural institutions, and residences that closely resembled factories (signified by Le Corbusier’s famous definition of the house as “a machine for living in”).

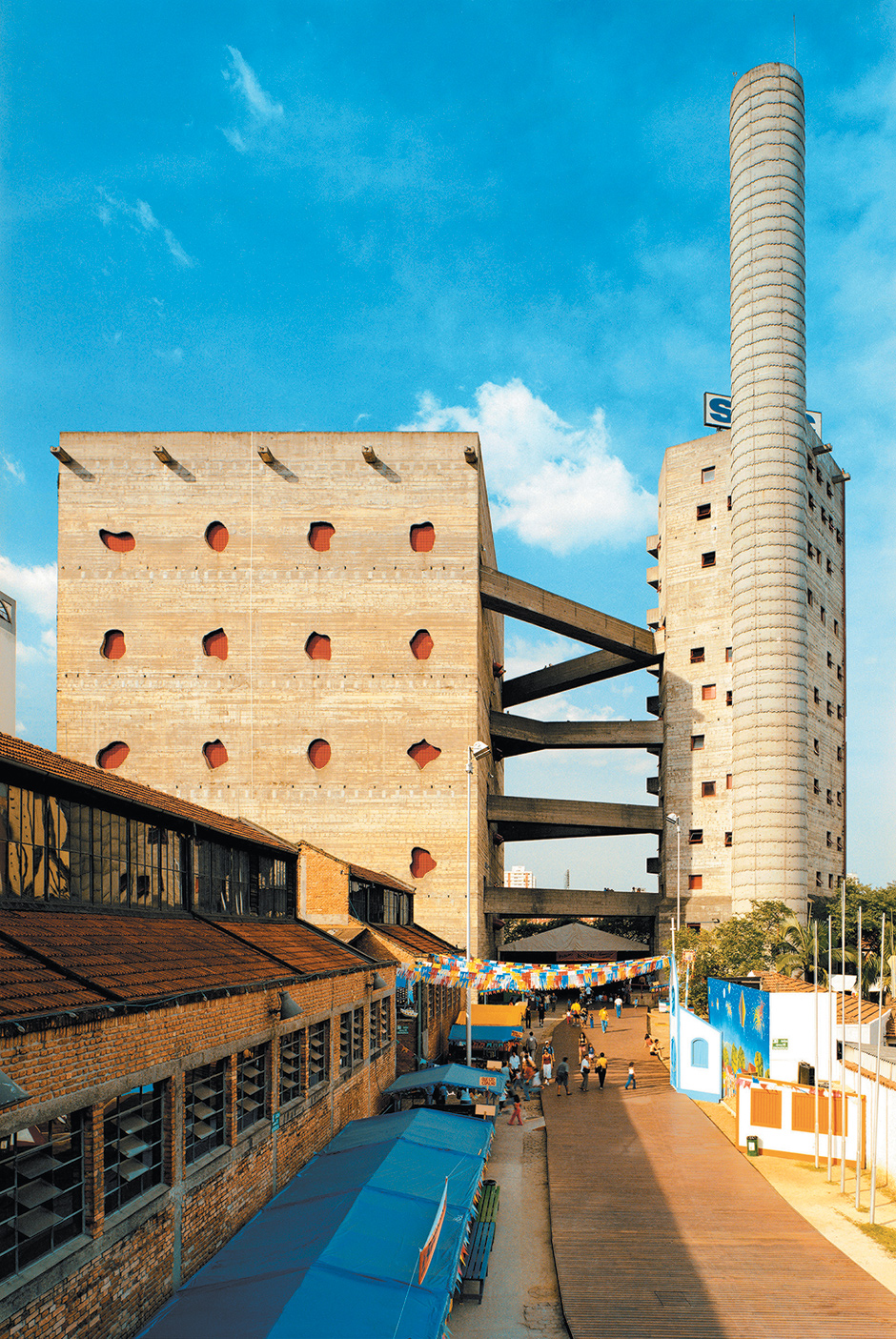

In 1971, Brazil’s Serviço Social de Comércio (SESC, the public outreach arm of the country’s trade organizations, established to quell unrest among laborers) acquired an obsolete 1938 steel-barrel factory in a working-class São Paulo quarter for a community center. SESC originally planned to tear down the prefabricated, reinforced concrete structure to make way for a new building. But the recent and much-publicized success of San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square of 1962–1965—an abandoned chocolate factory that the architect William Wurster and the landscape architect Lawrence Halprin reconceived as a hugely popular retail-and-restaurant complex that became a major tourist attraction—prompted the decision to retain the existing São Paulo structure.

Because it had already been temporarily retrofitted and clearly worked well as a neighborhood gathering place, Bo Bardi advised that this fine example of industrial architecture (based on the pioneering structural concepts of the French engineer François Hennebique) merely be tidied up and preserved. Into that imposing shell—dominated by soaring concrete volumes that bring to mind the monumental Brutalism of Louis Kahn—she inserted her comprehensive series of domestically scaled innovations, each fulfilling a specific function.

These included everything from her colorful and tactile interior and furniture designs to her programming for exhibitions and performances. In her egalitarian view of art, high and mass culture were presented without hierarchical distinctions in the center’s flexible display galleries. A wide range of educational and vocational activities are still offered in classrooms and a library, but there are also a full array of sports facilities (including a swimming pool), areas where people can play games, meet friends, and socialize in a variety of ways, as well as a theater and a community lunch restaurant that at night becomes a beer garden. As Lima writes:

SESC Pompeia offered a concrete example of one of Bo Bardi’s main pursuits: to show that “culture is a fact of everyday reality,” not a special event or even the domain of the educated elite…. [She] imagined it, as many in the center’s staff still do, as an antidote to consumer society and a space for human imagination and shared participation.

With the Pompeia commission, Bo Bardi cut out the middleman, as it were, by adapting an old factory while preserving its gritty character. This remarkable advance in architectural thinking anticipated by two decades the widespread vogue for recycling former industrial facilities into exhibition galleries, epitomized by Richard Gluckman’s transformation of a warehouse into the Dia Art Center in New York (1987) and Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron’s conversion of London’s Bankside Power Station into the Tate Modern (1995–2000). Furthermore, Bo Bardi’s celebration of her design’s workaday origins and its overwhelmingly warm reception make it a direct antecedent of New York City’s postmillennial public works wonder, the High Line (2003–2014), which likewise took a derelict piece of outmoded infrastructure and turned it into an instantly beloved community treasure.

On the cover of Zeuler Lima’s splendid new study is an image that perfectly sums up what might be called the Bo Bardi Touch. This black-and-white photographic detail shows an irregular opening cut into a concrete wall of the architect’s Teatro Gregório de Matos of 1986–1987 in the Brazilian city of Salvador (one of nine theaters she designed). Instead of the geometric precision associated with the Bauhaus, this amoeboid aperture—which she called a fustella (perforation punch, in Italian)—brings to mind a rougher version of the freeform outlines of Alvar Aalto’s biomorphic Savoy Vase (1936).

Executed with the nonchalant facture typical of Bo Bardi, this unruly form reminds us that she much preferred to focus on how architecture feels rather than the way it looks. Robert Venturi famously wrote, “I am for messy vitality over obvious unity,” and in that same spirit the designs of Lina Bo Bardi exert a vivifying and unifying effect that architecture can impart only when the need for a better social life is genuinely important to the architect’s imagination.

This Issue

May 22, 2014

How Memory Speaks

The Phony War?

Elizabeth Warren’s Moment