“Doctor, I want my hip bone.”

Doctor Padgett did a double take.

“I want my bone, you know, what you’ll be taking out.”

“Well, I don’t know about that,” he said, “you’ll have to talk to pathology about that.”

Down the hall, the pathologist said sure. A couple of weeks after surgery you can have it. (First they would have to conduct the routine tests on any newly removed body part.)

They both asked me the same question: “Why?” I wasn’t sure, I just knew I wanted it. Perhaps I didn’t want to part with the part of me that had caused me the most pain without having a final word.

So I got the OK. That and the promise of a small—well, smallish—incision, and I agreed after more than two decades of delay to go under the knife with the hope of trading more pain for less. Though being a ballet dancer, it really wasn’t to lessen the physical pain that I finally decided to have my hip replaced. It was because of the increasing loss of mobility. Life was getting smaller, and my hip was starting to rule.

At the age of twenty-three when I was dancing for Balanchine in the New York City Ballet, I was diagnosed with osteoarthritis in my right hip while on tour in Europe. It all began when I couldn’t swoop my right leg up to the side during the opening minutes of Serenade one night at Tivoli. After many exams and X-rays I got one of those “Honey, sit down, it’s all over, your career is finished” talks from the company orthopedist. Needless to say I did not obey, though I did have to go to bed for three months to allow the inflammation to subside. A year later, with the help of Indocin and daily physical therapy, I got back on stage and danced for another eighteen months. But then other injuries, the body’s compensation, started adding up and I knew the time had come.

I stopped dancing, but refused to give up my hip. It was my battle wound, proof of having attained victory over that great defiant physical act upon which all classical ballet is delicately perched: turn-out. (Contrary to common belief, true turn-out—the outward rotation of the legs so that the knees are pointing in 180-degree opposition—is a pivoting in the hip socket, not in the knees or feet.) One of the many ironies is that I lost the ability to turn-in: I was trapped turned-out. Ha! I suppose I thought that in keeping the bone after it was removed I was losing less somehow.

Not a very appropriate fear for a ballerina, for whom dancing is, by definition, a conscious act of loss. A ballet dancer goes onstage on a given night, in a specific theater, in a specific ballet and executes, in a specific fraction of musical time a movement that is already past just as it appears. And it takes far more than 10,000 hours of practice and repetition to make this movement exquisite, worthy. A dancer’s entire career consists of these moments of non-existence; they are not even fleeting, they are, somehow, never there at all, a shadow in someone else’s mind at best.

I first realized this at age seventeen, having already focused thirteen years on the pursuit of this particular kind of beauty. I had just been chosen by Balanchine to join his company, and when finally dancing his ballets on his stage, the real task at hand became apparent. I feared not having the courage to endure this kind of transience—this was spiritual work of a very high order; the physical work paled beside it. Terror sent me into a kind of scribbling frenzy in an attempt to salvage myself from what felt like complete extinction. (Surely dancing is the saddest of the arts in its fragility—for architects, sculptures, painters, writers, composers, musicians, actors, their work resides legitimately outside themselves. Not so dancers. And don’t talk to me about the two-dimensional horrors of video and DVDs!)

So now, decades later, I envisioned a parched white Georgia O’Keefe bone, my eroded femur head, on a shelf in my house, a fossil, evidence of those millions of lost moments dancing, now solid, externalized. Proof. (Of what? God knows.)

Two weeks after surgery, as promised, Mrs. Wong, my doctor’s office manager, called to say my bone was back from pathology and ready for pick up. Well, the Georgia O’Keefe fantasy quickly vanished. Sitting on Mrs. Wong’s desk in an opaque quart-sized Tupperware container with a crooked orange hand-written label were pieces of something floating in formaldehyde. She handed it to me, and suggested that if I was taking it on the airplane to California I should put it in my checked luggage so as to not concern security with the “What is THAT?” question, not to mention the liquid it was in.

Advertisement

Once back from the hospital I gingerly opened the container: nothing in there looked remotely like anything from an anatomy book. Now, Mrs. Wong had also told me that if I wanted to preserve my “souvenir” on dry land I needed to have a taxidermist extract the fatty tissues from the bone so it wouldn’t go rancid. One hundred thousand dollars of medical bills and I still needed a taxidermist.

Back in Los Angeles I let the Tupperware sit in its cocoon of bubblewrap in the corner of my dining room bureau for several weeks. Finally I Googled “taxidermists Los Angeles” and came up with several places. Game Master Taxidermy was the one closest to me. It was already 10 p.m. but I thought I’d call and see what information the recording would give me about hours and parking.

“Hello,” a man’s voice said.

“Oh, er, ah, sorry, ah—is this the taxidermist? I thought you’d be closed…”

“Yeah, this is the taxidermist and yeah we’re closed.” Images of him in some dark workshop drying out the dead late into the night came to mind. I explained that I needed my recently removed hip bone “treated” in some fashion. He warmed up a little. It was illegal, he explained, for him to have human bones on his premises—at least the kind that are free-floating. “But I can tell you what to do. It’s very easy,” he said cheerfully.

Here’s the recipe he gave me:

- Boil bones on the stove in plenty of water for one hour.

- Drain and soak in cold water for 30 minutes.

- Soak in a solution of 50 percent bleach, 50 percent water for twenty minutes.

- Let dry outside in the sun

Well, I’d come this far and I wasn’t going to stop now. But, what if, as they came to a boil, there was a smell? By now I had realized that step one was the same as making chicken broth and I wondered if I should have added a carrot and celery stick, a bay leaf and some whole peppercorns like my mother did. Human broth. What if my cats started yowling like they do when they smell chicken broth? But, I reasoned, I am not a chicken—and I wasn’t going to avoid smelling it. It was a rare opportunity. I stuck my nose into the pot like Julia Child and inhaled deeply. The aroma was mild and, well, not so bad.

As directed, I drained the pot into a colander observing, I’m proud to report, very little fat on the surface of the liquid. Less than with a chicken. And no, I didn’t save the broth. I’m not crazy.

There on the bottom of my red plastic colander that had held so many strands of pasta was my hip. Sort of. This was the first time I had really seen the pieces not submerged in liquid. I had to look in brief flashes to get used to it. There was me, the inside on the outside, and it sure didn’t look pretty. I had hoped to see the arthritis that had caused the end of my dance career at an age young even for a dancer. I wanted to confront the enemy and see that it was real. Even now, all these years later, I still think I should have been able to cure my injury, alleviate the pain and increase my motion with enough sleep, steak, cod liver oil, time, acupuncture, physical therapy, and Pilates. Like a child, I thought my bad hip was my fault. I wanted to face it now, to confirm somehow that I could not, with all the will in the world, have overcome it and danced again.

So there it was, the femur head in two halves (pathology had cut it in half). But there were numerous other pieces, bits, God knows what. Yuck. Maybe the bleach would, at least, turn everything white, purify it. It didn’t. And neither did the sun.

I have since brought my bones inside. I’m no longer scared of them, just curious. They simply don’t make any sense. I can look at my X-ray and see what got taken out but there are many rough, asymmetrical, curved, chunky, twisted, strange pieces that don’t fit. When I showed them to Dr. Padgett during a check-up back in New York (yes, I packed them up and took them on the plane back East again) he wrinkled his nose and drew back—not exactly how you want your surgeon to react to your insides, especially the parts he removed himself. He shrugged and said he had no idea what they were. Jeez. Then he explained that the smooth, mottled, marble-colored side of the femur head, the only part of the bone that was beautiful to me, was the “arthritis,” meaning the place where the cartilage was gone entirely: arthritis is an absence—pure, smoothed-down bone surface. Inside the sliced bone it looked like honeycomb.

Advertisement

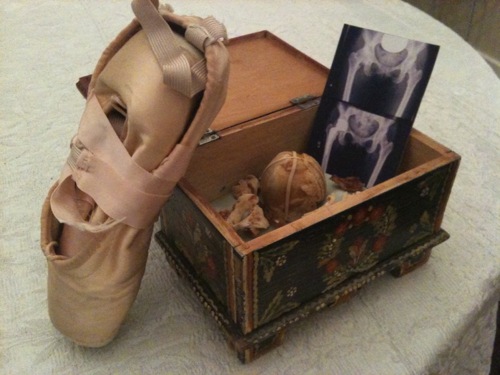

Maybe I’ll glue the femur head back together so at least it looks more like a femur head. For now an elastic band holds the two sides as one. But the truth is that all the pieces do not fit together and they never will. I guess they didn’t inside me either. That was the trouble. They sit now in a wooden box that belonged to Balanchine, that he painted himself, that I was given by Father Adrian who buried him. Next to the box, I keep the last pair of pointe shoes I ever wore on stage. The coffin of my career.