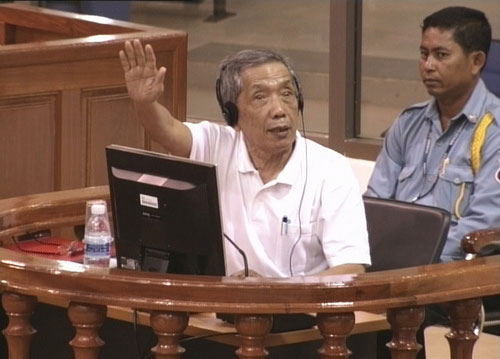

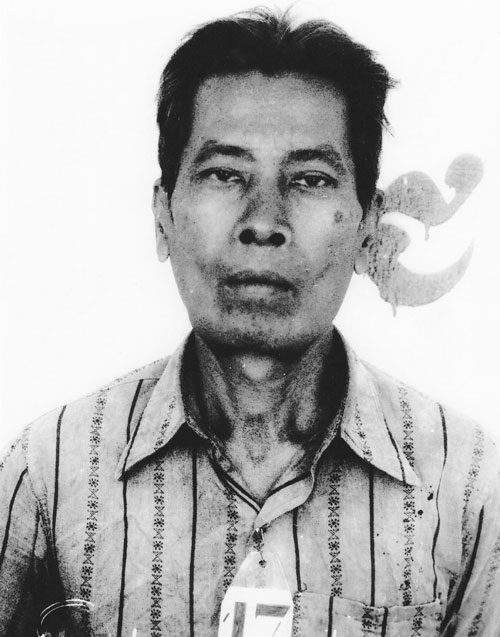

The July conviction of Kaing Guek Eav, better known as Duch—the gaunt-faced, fever-eyed 68-year-old head of the Khmer Rouge’s leading torture center—by a special UN–Cambodian criminal court has been seen as a breakthrough in international justice. Years in the making, the trial was the first international criminal case brought against an official of the Pol Pot regime since a Vietnamese show trial in 1979. And despite mixed legal procedures, the conflicting approaches of Cambodian and international lawyers, hearings in three languages, budget shortages, corruption scandals, and political pressure, it was widely considered fair. Yet it is unclear how much the Duch case will have advanced the long-delayed efforts for justice against the Khmer Rouge, not least because Duch himself seems to have come out of the experience less repentant than he was when it began.

For his part in overseeing the torture and execution of at least 12,273 prisoners, Duch was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and sentenced to a 35-year prison term, with 19 years left to serve. But after spending much of the 77 days of court hearings expressing remorse, he is now appealing the sentence and asking to be released, claiming that he was neither one of the regime’s leaders nor among those “most responsible” for the Khmer Rouge’s atrocities, the only people the special court in Phnom Penh is entitled to try. This request reflects a dramatic last-minute shift in the defense’s strategy, from cooperating with the court to disputing its authority to judge Duch. That Duch could undermine the trial and its outcome in this way highlights its central flaw: all along, he was allowed to dominate the telling, and so influence the judging, of his own crimes.

From the moment the hearings began, in April 2009, François Roux, Duch’s French lawyer and a veteran of international criminal courts, built a canny defense around a story of redemption (an approach that Duch’s second lawyer, the Cambodian Kar Savuth, seemed to share initially). Yes, Duch had signed up for a revolution and had sinned in its name, Roux argued, but he had also acted in terror of a paranoid regime; Duch had been both “a servant and a hostage” of the Khmer Rouge. Now, he was atoning for his crimes and asking for forgiveness—or better yet, for the possibility that he might be forgiven one day. Duch would cooperate with the court and tell the victims’ families all that he knew about what their lost relatives had endured. In exchange, Roux asked them, the judges, and the audience to allow Duch “back into humanity.”

That was a lot to ask considering that the court’s own count of Duch’s victims was conservative. Historians estimate that as many as 20,000 may have been killed at S-21, a secret prison set up to extract confessions from Khmer Rouge enemies—mostly suspected traitors among party cadres—and then to eliminate them. In order to draw attention away from the pulled nails and the force-feeding of feces, the waterboarding and the bleedings that Duch had overseen there, Roux framed the debate instead around Duch’s moral reconstruction, casting him as a tragic figure trapped by circumstances he has since repudiated.

It helped that the trial’s first witness was François Bizot, a French ethnographer briefly detained at and released from M-13, a jungle prison and precursor of S-21 that Duch ran in the early 1970s. Bizot was the rare case of a prisoner freed and of a prisoner unusually empathetic toward his captor, and Roux deployed him as a court expert on torturer-saviors and all manner of gray areas. Bizot’s judgment of Duch was by no means kind—“There is, it seems to me, no forgiveness possible”—but his nuanced testimony gave Roux a chance to retrieve his client from beyond the pale. “I felt that [Duch’s] crime was the crime of a man,” Bizot told the judges, “and that its abomination should be measured not by treating Duch like a monster but by rehabilitating, or rather recognizing in him, the humanity that is his, as much as it is ours.”

Roux sought to bring out Duch’s psychological complexity by making him tell a harrowing story about Sok, a young prostitute detained at M-13 on suspicions that she was a spy. Duch had set out to torture her by exposing her, drenched, to cold winds. But the experiment failed: she didn’t confess. Moreover, the sight of her clothes clinging to her body had stirred him, he said to the court, sparking fears that his staff might abuse her sexually and that such a slip-up could bring tough, perhaps lethal, sanctions from his superiors. When Duch was ordered to have Sok executed, he obliged.

Advertisement

“What do you have to say today?” Roux asked. “At the time, under that regime, there was no alternative but to respect party discipline,” Duch answered. To contain his emotion at such moments, he added, he would recite the closing verses of the nineteenth-century French poet Alfred de Vigny’s “Death of the Wolf”:

Weeping or praying—all this is in vain.

Shoulder your long and energetic task,

The way that Destiny sees fit to ask,

Then suffer and so die without complaint.

A week into the hearings, Roux had managed to cast Duch in the role of pained, and now penitent, executioner.

Duch played the part well. Before the trial, he guided the investigating judges through reams of execution orders and prisoners’ confessions, deciphering notes and identifying handwriting; he explained S-21’s organization and its relation to the Khmer Rouge leadership—ammunition for a second trial against four top officials, which is expected to begin next spring. In court, Duch was unfailingly attentive, well-informed, and meticulous. During one early hearing, hunched over a copy of the indictment, a yellow highlighter in hand, he listened without flinching to the crushing enumeration of 238 uncontested allegations about atrocities committed on his watch: “S-21 was set up to ‘smash’ political opponents,” “a child was thrown from the third floor.” Even though every flick of his wrist seemed to be an admission of guilt, his self-possession somehow exuded authority.

Soon, he was correcting shoddy, sometimes appalling, translations by court interpreters: he had “ascertained” this fact or that, not “seen it with his own eyes.” He was obsequious with the judges (“Thank you for asking this question”) while condescending to the lawyers (When an especially emotive one asked, “Do you not understand my questions?” he responded, with a smile, “Maybe you don’t understand my answers.”) One day, he called into question the identity of one Ly Hor, who claimed to have been a prisoner at S-21: “If one compares the handwriting in document 00279927 to this one, the two are 50 percent different. Therefore, I estimate that comrade Ear Hor and Mr. Ly Hor are not the same person.” QED. Once a model math teacher, then a model interrogator and prison warden, Duch was now a model defendant.

In contrast, the performance of other participants in the trial was often feeble. The prosecutors kept changing and generally seemed underprepared. They relied on materials gathered by NGOS and journalists more than on their own investigations; once, to prove the widely known fact of S-21’s enforced squalor, they tried to present footage from a feature film. Lawyers representing the victims and the victims’ relatives who joined the case as civil parties grilled S-21 guards and interrogators called in as witnesses as though it was they who were on trial, not Duch. (In fact, such low-level officials did not exercise enough authority under the Khmer Rouge to fall within the mandate of the tribunal.) As a result, these valuable sources clammed up, disclosing far less about Duch than they knew.

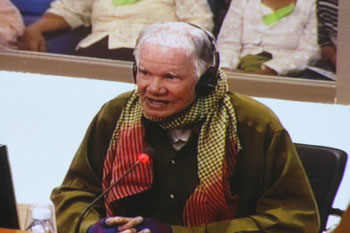

That left Duch often seeming like he was in command. At no time was this more evident than in his handling of Mam Nai, S-21’s chief interrogator and perhaps the trial’s most important witness. About half-way through the trial, in July 2009, Mam Nai was called to testify about the torture of Phung Ton, the dean of Phnom Penh University, a former professor of Mam Nai’s and Duch’s, and the only S-21 prisoner about whom Duch had ever choked up in court. The unusual-looking Mam Nai, very tall and almost albino, wearing mittens in the sticky heat, spent a day and a half not remembering, equivocating, and lying in the face of incontrovertible documents and his own earlier statements. (Roux had something to do with this, having repeatedly reminded Mam Nai of his right to remain silent if he feared incriminating himself.) Then came Duch’s time to comment on his testimony. Duch stood up, in a bone-white polo shirt and high-riding dark slacks, and announced, pointlessly it seemed, that back in the day he had preferred another of his assistants. Then, cleaving the air with his mangled, four-fingered left hand, he began to scold Mam Nai: “We are here being judged by history, and one cannot cover up an elephant with a basket. So don’t try!”

Spotting the opening, the lawyer for Phung Ton’s family invited Mam Nai to “elaborate” on his earlier answer. Unshakeable until then, he started to weep. “I would like to express my regretfulness to the family of Professor Phung Ton,” Mam Nai said, wiping his face with a checkered krama. But he would say nothing more about what had happened to the professor, claiming, unconvincingly, that to try would be “like shooting in a dark night.” A blow to Phung Ton’s wife and daughter, who were in court, this was an ideal outcome for Duch: he got to look like a truth-teller without having to do any telling himself or being exposed by someone else’s.

Even more disturbing, Duch’s dismissal of Mam Nai demonstrated that his talents as an interrogator endured. Withdrawing approval, shaming, intimidation—the skills Duch used against Mam Nai are what had gotten him into the defendant’s box in the first place. In the days of S-21, these tactics had allowed him to wrest confessions from desperate detainees; in court, they ensured that nothing would be extracted from him. The more he claimed to admit, the more he managed to avoid.

Duch’s blanket acknowledgments of responsibility worked in much the same way. He liked to repeat that while he hadn’t tortured or killed anyone himself, he was responsible for ordering his subordinates to do so. And the more he said this, the more, by implication, he was indicting his own superiors for the orders they had given him. By September 2009, as the hearings were wrapping up, self-indictment had come to sound like evasion.

Then came the baffling turnabout. In late November, during closing arguments, Duch’s Cambodian lawyer, Kar Savuth, himself a former prisoner of the Khmer Rouge, abruptly asked for Duch’s release. Because Duch was not among “those most responsible,” Kar Savuth claimed, he should be set free. Roux was stunned. The objection should have been raised months earlier, and it torpedoed the defense that he had built around Duch’s contrition. The break, however, was final: citing a “loss of confidence,” Duch sacked Roux a few months later, just weeks before the verdict.

The request for Duch’s release was a gamble, as it could cast doubt on the sincerity of his professed willingness to be held accountable. And it did, though with little consequence. In their verdict of late July, the judges—three Cambodians, two internationals—did call Duch’s expression of remorse “limited” but nonetheless shaved five years off his prison term to reward him for cooperating. Duch’s version of events also carried the day on many contested factual points, including how many prisoners had been bled to death (“at least 100,” Duch’s estimate), whether he had ever attended any executions (some witnesses said yes; he said no), and how much torturing he did himself (none, that could established).

This was probably as good an outcome as Duch could have hoped for. But why risk much worse by asking to be set free? Duch—or was it Kar Savuth?—seemed to be playing a longer game. Rumors started circulating that Kar Savuth was setting the stage for an early release a few years into Duch’s sentence. Certainly, Duch and Kar Savuth, who has also acted as a legal adviser to Prime Minister Hun Sen, seemed to be opening a side conversation with the authorities. Last summer, Duch hired a second Cambodian attorney to replace Roux, turning the defense team into an all-Cambodian affair, presumably the better to wash the Khmer Rouge’s dirty laundry in private.

This must have been a welcome signal to the Cambodian government, which has been wary of these trials from the beginning and has been quietly exerting pressure to limit their scope. Hun Sen, himself a former Khmer Rouge (though one who defected early enough to be safe from prosecution today), has acted testily about them, sometimes even threateningly. When last year the Canadian co-prosecutor Robert Petit began eyeing six more suspects, including two army generals, in addition to Duch and the four Khmer Rouge leaders who will be tried next year, Hun Sen warned that further indictments could trigger civil war. The Cambodian co-prosecutor got the hint and opposed expanding the investigations. (Petit eventually quit.) Hun Sen also recently backed six sitting officials—two ministers, two senators, and the presidents of the senate and the national assembly—when they refused to answer the court’s summons to testify for the upcoming leaders’ trial.

Kar Savuth sounded a curious echo to these rumblings from the government when he first called for Duch’s release last November. To single out Duch as the only mid-level officer worth trying would amount to scapegoating, he argued, and since the government would not allow anyone else to be prosecuted, he intimated, Duch must be released. Thus by the trial’s close, implausibly, the Cambodian government, the Cambodian prosecutor, and the Cambodian defense were making common cause.

It was a singular outcome. As the first serious legal reckoning with the Khmer Rouge’s mass killings, Duch’s trial was a milestone. Yet with Duch able to manipulate the proceedings to his advantage, and all the external political maneuvering to limit the court’s reach, the case may ultimately have revealed as much about the dark dealings of Cambodia’s current leaders as about the cruelties of Pol Pot’s rule.