Cooking odors grow stronger as visitors approach the gallery where Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen—a stimulating show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art on food preparation in the twentieth-century home—is installed. Although the aromas actually emanate from a café next to the second-floor exhibition, the pervasive food smells that can be so distracting throughout the restaurant-riddled MoMA are for once appropriate here.

Counter Space was conceived in part to show off the design collection’s most important recent acquisition, a rare unaltered example of the mass-produced Frankfurt Kitchen. This standardized, modular all-inclusive unit was designed in 1926-1927 by the Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (more familiarly known as Grete Lihotzky) for Frankfurt’s ambitious program of municipally funded International Style workers’ housing estates erected during the zenith of the social-democratic Weimar Republic.

MoMA’s kitchen, from the architect Ernst May’s Höhenblick settlement in the Frankfurt suburb of Ginnheim, is the smallest of three variations devised by Lihotzky for different residential developments. In a space less than thirteen feet long, seven feet wide, and nine feet high, Lihotzky (who died in 2000, days before her 103rd birthday) reconfigured the kitchen in the spirit of the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American domestic reformers Katherine Beecher and Christine Frederick, who espoused rational organization and efficiency.

As Frankfurt’s master planner, May had embarked on a building program of some 15,000 flats, recruiting Lihotzky, then an associate of the Viennese minimalist Adolf Loos, to join his design team. By operating within industrial guidelines of interchangeable parts, Lihotzky could mass produce her Frankfurt Kitchen at low cost for all the new Siedlungen (settlements, or housing estates). As Susan R. Henderson writes in “A Revolution in the Woman’s Sphere: Grete Lihotzky and the Frankfurt Kitchen”:

Lihotzky’s points of reference were far removed from the woman’s sphere: ship galleys, the railroad dining car kitchen, and the lunch wagon….[W]ith Lihotzky, the kitchen came to full maturity as a piece of highly specialized equipment—a work station where all implements were a simple extension of the operator’s hand.

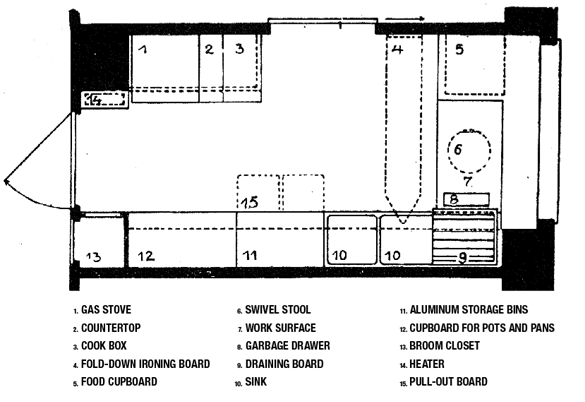

Following the time-motion studies of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Lihotzky positioned the gas range, industrial-style metal sink, and fitted glass-fronted cabinets in optimal relation to each other, arranging them to coincide with the general order of tasks through which meals are made and cleaned up after. MoMA’s Frankfurt Kitchen is set up to allow one to peer through its doorway on one long wall and window at one short end. The ensemble is so intelligently organized to maximize das Existenzminimum (the basic requirements for living) that it could only have come from the mind of a woman who had experienced firsthand the illogic, drudgery, and waste of traditional kitchens.

For all Lihotzky’s emphasis on modern innovation—notably the application of assembly-line techniques perfected by Henry Ford—her kitchen-in-a-box was a low-tech affair, not only because of strict budgetary restrictions (the local government limited the cost of each kitchen to one-and-a-half times an average worker’s monthly salary, an amount amortized through rental fees) but because labor-saving electrical appliances were not yet generally available. For example, Lihotzky specified no refrigerator, which was considered a superfluous extravagance at a time when people shopped daily, and in a place where it rarely got very hot in summer.

Among her unplugged labor saving devices was a built-in grid of eighteen drawer-like aluminum containers for sugar, flour, rice, and other dry foodstuffs. Each neatly labeled, removable compartment had a handle and spout that allowed it to be lifted out and the contents poured. A slatted wooden dish-drying rack was set into a shelf over the sink, which let water drip directly down the drain. And a hinged upright ironing board, like a Murphy bed, pivoted horizontally next to the window to take advantage of daylight.

Reactions to the Frankfurt Kitchen’s tight dimensions tend to vary depending on where one lives. New Yorkers inured to minuscule galley kitchens won’t find this snug space claustrophobic, but will covet the window, a luxury amenity in city apartments.

Many, however, are likely to be caught short by the MoMA kitchen’s battleship-gray cabinets and drab linoleum-covered work surfaces, unfathomably austere for a country where a disproportionate amount of our gross national product goes toward granite countertops. In 2005 London’s Victoria & Albert Museum salvaged another intact exemplar from the same Höhenblick estate, but it is painted a more pleasing blue-green color than New York’s soberly utilitarian version.

Advertisement

Perhaps worried that their Frankfurt Kitchen might not make enough of a splash by itself, the organizers of Counter Space—Juliet Kinchin and Aiden O’Connor of the museum’s architecture and design department—garnished their main course with some 300 more-or-less related design and art objects from MoMA’s holdings. Once again we see the overly familiar Chemex glass coffee maker, the plastic Tupperware, Kaj Franck’s Arabia ceramic dinnerware, and Philippe Starck’s inescapable Alessi aluminum citrus squeezer.

Further stuffing is provided by multiples of Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box (1964), and assorted wall art with a culinary theme. Some of this material seems very tangential indeed, but all is redeemed by James Rosenquist’s glorious 1980 canvas of two radiant egg yolks in a gleaming metal mixing bowl (given by Philip Johnson and David Whitney, those reliably impeccable connoisseurs).

Thanks to feminist historians since the 1970s, growing awareness of women’s contributions to the modern building art has revived the reputations of such neglected pioneers as Eileen Gray, Lilly Reich, and Charlotte Perriand, who overcame prejudice against the involvement of women in anything architectural beyond decorative embellishment. Thus it is gratifying to see Grete Lihotzky—whose deep political engagement impelled her to join the Austrian Resistance in 1940, leading to her imprisonment by the Nazis for almost five years—finally receive historical recognition.

The power of olfactory suggestion being what it is, one exits this thought-provoking display drawn to the smell of espresso brewing in the adjacent snack bar. But given the wonderfully corrective nature of Counter Space, which restitutes another long-forgotten heroine of the Modern Movement, could that be the odor of domestic sanctity?

Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen is on view at The Museum of Modern Art in New York through March 14.