I was lucky to be invited to see Bob Dylan’s paintings when I was in L.A. this past winter. Part of the seeing was how I got there. I’m not going to tell you exactly where it was, but getting to his studio was like that scene in Goodfellas when Ray Liotta parks his car outside a nightclub … I think it’s Copacabana … and goes in a side entrance, down a hall past a lazy-ass watchman, into the kitchen, through another hallway, and out into the main room and ends up right next to the maître d’, who then ignores the people in line waiting to get in and hugs and kisses Ray and his girlfriend and shows them right down in front of the stage, where a small table, two chairs, and a plug-in lamp suddenly, miraculously, appear.

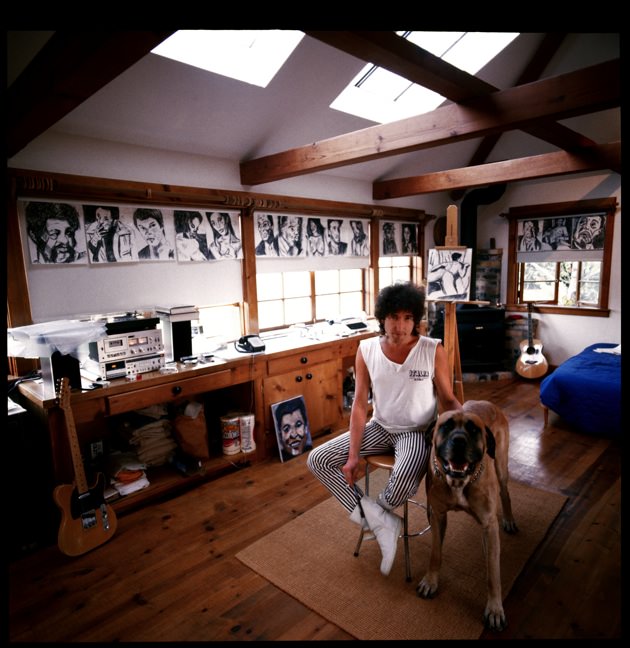

Dylan’s studio. I think it was Dylan’s studio. I’m still not sure. It didn’t look like any artist’s studio I’d ever been in. It was on the second floor and was around five hundred square feet and furnished with furniture that looked like it had been found on the street. There was a small Casio keyboard on a keyboard stand. There was a store-bought easel and a carton of art supplies on the floor. The carton was one of those plastic containers the USPS holds mail in. I’m not sure what was on the wall. I think there was a gold record or a plaque that said something about a record industry milestone. There was a small balcony with a couple of wrought-iron chairs and a table. It was a mismatched set. Except for the art supplies, there wasn’t a single thing in this room that would tell someone, “Art is made here.” It was kind of astounding. It was like Dylan was painting in a witness protection program.

Maybe that’s my way in. That kind of thought. “The Fugitive.” That’s how I should think about his art. I’m always looking for a way in, and I think I’ve found it. I know he paints on the road. In hotel rooms. And there are a lot of hotel rooms—he goes all over the world. And when he isn’t playing music, he’s painting. That day he showed me twenty paintings. The first thing that hit me was how complete they were. And the fact that he knew what he was doing.

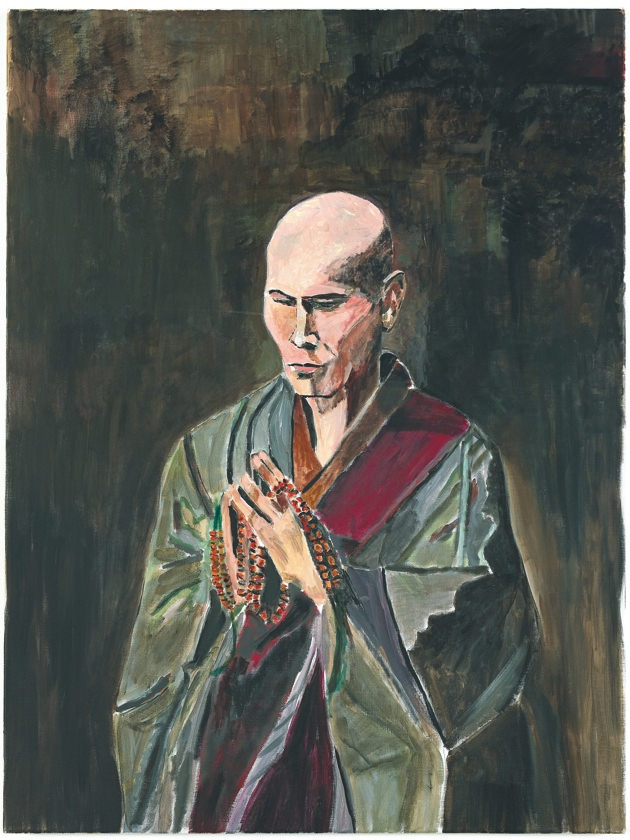

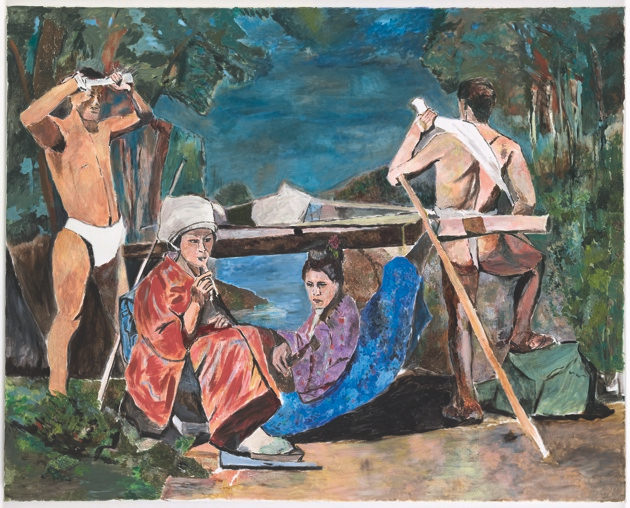

I think Dylan’s paintings are good paintings. They’re workmanlike and they do their job. They’re not trying to be something they’re not. I’m not sure he’s even aware that there’s a style that can sit beside Arthur Dove, Charles Burchfield, John Marin, Charles Sheeler. The amount of paint is measured. And the color is always within a defined degree of browns, beiges, and yellows. There’s never any interruption in the way the surface is painted, and this is why I think they’re special. That’s hard to do. When you’re painting a whole scene, whether it’s a portrait or a boat going up the canal or a view outside your hotel window and you’re trying to get the trees to fuse into a path a man is walking on … it takes something that’s instinctive instead of learned. I looked at his painting of a Chinese farmer herding a big-horned cow and marveled at the breadth of the horns and the way the horns melted into the figure of the farmer. “Man,” I said, “that’s some strange cow.” That’s what I thought about D.H. Lawrence’s paintings. Different subject matter, but the same struggle to represent. Same amount of paint. Same palette. Same use of line to accent the contours of what’s real. If you don’t know D.H. Lawrence’s paintings, you should. It’s kind of hard to see them—a few are in an out-of-the-way hotel in New Mexico and a few are in Texas, but most of them are lost and any reproductions of them are pretty dull and underimagined.

Other writers who painted and had a similar way of representing what they saw: E.E. Cummings, Jack Kerouac, Sylvia Plath, Henry Miller …

The paintings that Dylan showed me out in L.A. were paintings from his travels in Asia. Some of them looked too big for him to have painted them while he was there, so maybe he had done them from memory or a photograph or a sketch or a drawing. I didn’t ask. I didn’t ask a lot of things. I didn’t need to. I just enjoyed the experience. I liked a painting called La Belle Cascade because it looked to me like one of Cézanne’s Bathers. And Cézanne’s Bathers are some of my favorite works of art: The paint is nice and thin, like it’s been applied directly on the wall of a Roman emperor’s home. I’m not sure of the time they’re set in—it could be any time. And the geometry is interesting. It’s real. The lines break up the space as if he was anticipating Cubism.

Advertisement

Most of what Dylan paints is straightforward. There’s nothing really to be interpreted or guessed at, and the rendering seems to say, “I don’t want excitement, and I don’t want to be exciting.” If I were to describe the painting in musical terms, I would say they’re more acoustic than electric.

The reclining figure in a painting of his called Opium looks that way because there’s a limitation in Dylan’s ability to draw and paint the figure. And that’s why it’s good. He doesn’t try to hide what’s limited and instead uses that limitation to try to make it his own, to try to make it look different and new. (Remember that Dylan once said he could sing as well as Caruso.) The figure has a strange foreshortening. The hand on the hip ends up looking that way because, like the rest of the figure, it’s part of the whole painting. It’s not any more considered than the handle on the door. Good art exists because of what you can’t do, not because of what you can do. What’s the point of skills and technique? What Dylan has is what no one else has … himself. Giving yourself permission, not waiting for a green light, is half the battle. The other half, according to T.E. Lawrence, is “for the fun of it.”

I don’t think Dylan is interested in the avant-garde, much less in contemporary art. I think he’s already pushed enough buttons with his music. (I’ve heard the story about him meeting Warhol and after the meeting taking away an Elvis silkscreen painting and then trading the painting with his manager for a couch.) What informs his painting can be traced right back to the drawing that was used for the cover of Planet Waves. The beginning of time: that’s what it says. Almost like there’s no language, and the only way to communicate is to make marks on the wall of a cave. That’s why there wasn’t much to say when I visited his studio. I didn’t need to talk. And he didn’t feel the need to explain. When I said I liked his painting Kitchenette, he said, “Oh yeah? What do you like about it?” “Well,” I said, “correct me if I’m wrong, but the whole painting looks like sea glass.” That’s all I could think of. When I look at that painting now, I realize my words were right. Something the ocean can’t help but do.

This essay is drawn from the catalog of “The Asia Series,” an exhibition of paintings by Bob Dylan on view at Gagosian Gallery until October 22.