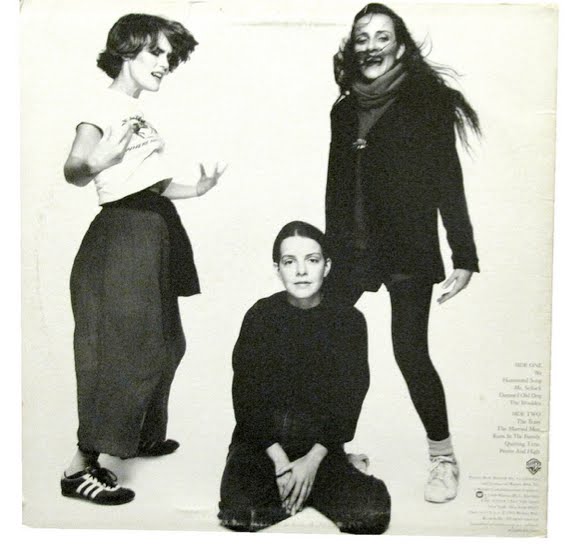

Suzzy Roche is mostly known as the youngest member of the three-sister band The Roches. The heyday of their somewhat cult following (“cult” in this case meaning “passionate, but shy of glamorous commercial levels”) began in the late seventies and crested in the mid-eighties. The Roches themselves hung on professionally in various combinations and incarnations into the 1990s and beyond; Suzzy has recorded both alone and with her sister Maggie. Many a fan has stared at their album covers, contemplating Ms. Rocheʼs long dark hair, her playful stances, her scrawny baby-of-the-family girlishness while trying to figure out which voice is hers in the [tight, intricate harmonies]( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9e3sqtoRG-Y=”Hammond Song”) that fill the Roche’s recordings. What might be less well known is that Suzzy Roche—who is now in her mid-fifties—is part of a larger musical clan: with the folk singer Loudon Wainwright she has a daughter, Lucy, who is also a singer-songwriter and whose half-siblings are Rufus and Martha Wainwright, the children of Kate McGarrigle of the much-loved [McGarrigle Sisters]( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGm2l6xrNmo=”Walking Song”).

The Roche-Wainwright-McGarrigle intertwinings comprise a musical family the sprawling brilliance of which has not been experienced perhaps since—well, we wonʼt say the Lizst-Wagners—but at least the Carter-Cashes. The extended family oeuvre, though varied, often has a conversational, smart-kids-at-summer-camp quality that is both folky and jokey. The Rochesʼ own wistful, clever songs are written with a sweet street spontaneity and prosody, and their clear, pure voices are like a barbershop trio of sassy angels. Sometimes they are overdubbed, to enlarge the sound, and the effect is close to celestial. But most often they sound like plucky girls riding home on a school bus, making things up as they go along. Their lyrics have unexpected line breaks and enjambment. In “The Train,” from the Roches’ first album, Suzzy writes, “I sit down on the train/with my big pocketbook/the guitar and a sugar-free drink/ I wipe the sweat off of my brow/ with the side of my arm/and take off all that I can/ I am trying not to have a bad day/everybody knows the way that is.” In the later song “My My Broken Heart,” she pines, “I would be as good as maybe grandma /but I must get a grip on/my,my broken heart.” In “My Winter Coat” the Roches sing (a la Lorenz Hart) “The cuffs are purple which perfectly suits/ a pair I already had of boots.”

The Wainwrights, each performing before their individual audiences (in 2006 Rufus—a crooning balladeer who, like his father, has a bleak comic streak—devoted an entire Carnegie Hall concert to the songs of [Judy Garland]( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWu7WDrnM1c&feature=results_main&playnext=1&list=PLF9AB2E381DA516F9=”The Trolley Song”)), write and sing with a similarly loose, improvisatory aspect. The 1970s novelty song “Dead Skunk in the Middle of the Road” by Loudon Wainwright has been the biggest family hit and atypical for all. The McGarrigles were renowned Canadian musicians, their most famous and beautiful song, “Heart Like a Wheel,” [covered by Linda Rondstadt]( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDrkUmxrxpQ&feature=related=”Heart Like a Wheel”). But despite—or maybe in keeping with—their penchant for the whimsical and ad hoc, the Roche sisters have been the most adventurous and original act in the family and have even recorded amusing yet exquisite a capella versions of compositions by Handel and by Cole Porter.

If Suzzy Roche were to sit down and write a novel that was not about music and family, what a disappointment that would be. But not to worry: her charming and agile literary debut, Wayward Saints has as its protagonist a famous musician named Mary Saint, who is finally going home to Swallow, New York, the small town where she grew up, in order to give a concert there. She will as well reunite with her mother and dedicate to her the (fictional) rock hit “Sewer Flower,” whose Rochean lyrics include “she grew out of cow dung and a dirty little song was sung” (Roche herself has written a song to go along with the novel—“It’s what you are/not what you ain’t/you’re a wayward saint”). Whether Mary deigns to lay eyes on her father, who terrorized her childhood and is now sitting quietly in a nursing home, remains to be seen.

Despite the broken family that forms the emotional backdrop of her tale, Rocheʼs descriptions are emphatically familial: not only are friends a family, glimpsed deer are a family, and trees are a family. “Far into the woods, back behind the camp, stood a circle of evergreen trees and most days I wound up there. Now I know that those trees were actually a family, and I’ll tell you how I know that, too. I must have sensed it because I liked to sit right in the middle of their circle and sing.” Sisterly beams of light shine down in slanted columns: the stage is set and lit by nature. In this transcendental setting Rocheʼs heroine Mary Saint also experiences a vision of the “Other Mary”: ”She told me that all the slanted beams of light belonged to her, and not to God, and she also let me in on the secret about the trees being a family.”

Advertisement

A mystic Catholicism haunts the bookʼs pages as do more pagan gods. The narrativeʼs guiding of her heroine home for her concert is gingerly and mythic, as if Mary Saint, with her dark celebrity, were a kind of Euridice, who has been kidnapped into some unknowable world ruled by devil fame, and who might not complete the journey out if the anxious loved ones turn expectantly and look with too much eagerness. It is ironic that the mother who awaits gazes and gazes without ever properly seeing. She looks at her daughter with the same flummoxed perplexity that any mother of a rock star might. “The two women sat looking up at the moon and stars. Mary pointed out the different constellations to her mother, and although Jean couldnʼt really see the shapes, she told Mary that she could.” Those lines are this warmly matter-of-fact bookʼs nimble benediction: a motherʼs incomprehension, a daughterʼs mystery, the heavens looking on. Can we get an Amen.

Wayward Saints will be published on January 17.