The writer Flannery O’Connor kept a pet chicken when she was a small child and trained it to walk backward—it was the subject of a 1931 Pathé film “short,” a brief human interest story that came between the Pathé news and the feature picture show. The five-year old Flannery was in the picture “to assist the chicken,” but later said that it was “the high point” in her life, adding, “Everything since has been anticlimax.”

When I began studying her linoleum cuts that short film came back to me. It came back for the simple reason that linoleum cuts are drawn and cut backwards. Her prints are naïve in their craftsmanship. But so what? One does not really expect accomplished, sophisticated art from a college student, much less in a college newspaper, and in this O’Connor is not an exception.

I suspect that most of them were done inside an hour’s time. If not, then she was dawdlin.’ This is very much in keeping with the medium. When worked warm, as on a hotplate, linoleum cuts like butter. The cutting tools meet little, if any, resistance. It cuts quick and easy. Later in her life she would say that the things that she worked on the hardest were usually her worst work. She also said that a story—or a linoleum print, if you will—has to have muscle as well as meaning, and the meaning has to be in the muscle. Her prints certainly have muscle, and a lot of it.

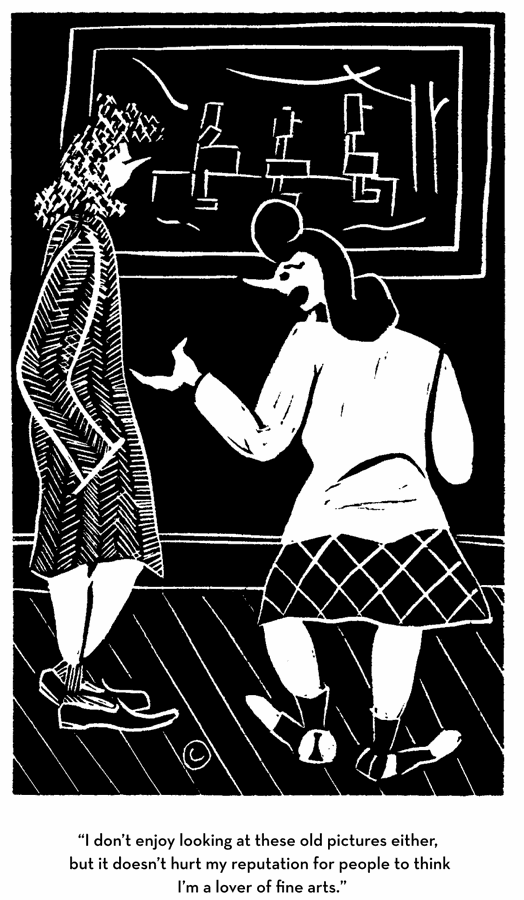

Her rudimentary handling of the medium notwithstanding, O’Connor’s prints offer glimpses into the work of the writer she would become, especially, and naturally I suppose, in her captions. Consider these delicious little O’Connor petards aimed at the walls of pretentiousness, academics, fashion, student politics, and student committees:

“It breaks my heart to leave for a whole summer.”

“Do you have any books the faculty doesn’t particularly recommend?”

“I don’t enjoy looking at these old pictures either, but it doesn’t hurt my reputation for people to think I’m a lover of fine arts.”

“I think it’s perfectly idiotic of the Navy not to let you WAVES dress sensibly like us college girls.”

“I wonder if there could be anything to that business about studying at the first of the quarter?”

“Do you think teachers are necessary?”

“Understand, I got nothing against getting educated, but it just looks like there ought to be an easier way to do it.”

“Targets are where you find them.”

“Wake me up in time to clap.”

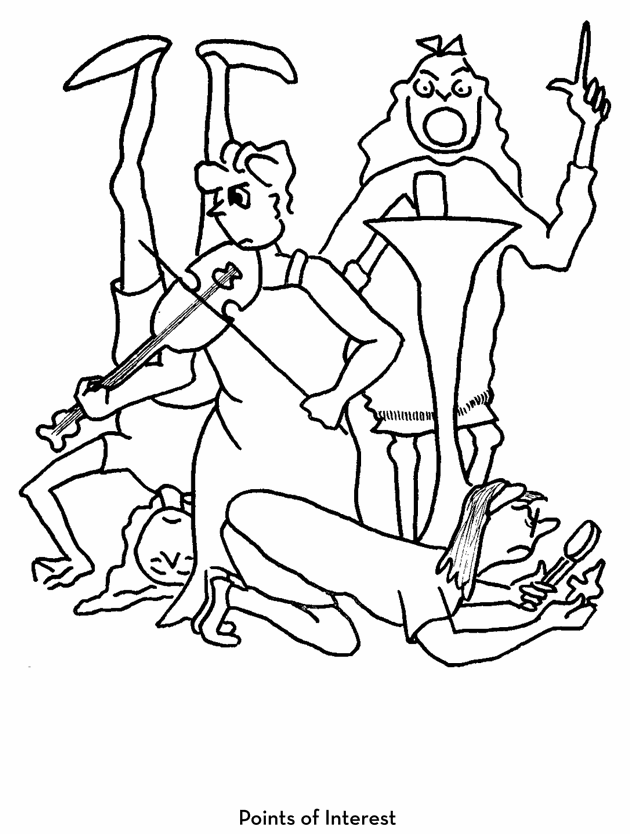

O’Connor maintains a technique that is consistent from one print to another, an accomplishment in itself. Most young printmakers can’t decide whether to go this way or that, and end up going in many directions at the same time.

Obviously she did not work from the live model or from any other form of visual reference to make these prints and this is another part of their appeal. In 1963 she wrote Janet McKane, an epistolary friend in New York, about a self-portrait with a pheasant cock she had painted, saying that when she painted it she did not look at herself in the mirror, nor did she look at the bird. “I knew what we both looked like,” she wrote.

Because her prints are not referential, I appreciate all the more her innate comprehension of gesture. I have taught life drawing for many years, and getting students to understand gesture is often the hardest part of the job. And it is that aspect of her graphic work that is most striking to me: the naturalness of figures walking, reading a newspaper, carrying a heavy burden, scratching the head, nursing a sore back, leaning against a post, strutting, standing at attention or at a lectern.

This understanding of gesture flows over into her fiction. Take for example the problem she has about the final meeting of Mrs. May and the bull in her short story “Greenleaf”: “My preoccupations,” she wrote to her friend Betty Hester, “are technical. My preoccupation is how am I going to get this bull’s horns into this woman’s ribs?”

O’Connor also had a strong, natural sense of composition that becomes evident after studying the prints. The overall pattern of “Oh well, I can always be a Ph.D.,” is a good example. She divides the rectangle into many near-repetitive black shapes, contrasts them with smaller, similar shapes in white, and then throws in a series of circle-like shapes and bold, angular stripes—all in all it reminds me, distantly, of Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror (1932), or Marsden Hartley’s Portrait of a German Officer (1914), or George Grosz’s The Guilty One Remains Unknown (1919).

In a letter to Robie Macauley dated October 13, 1953, O’Connor says that she read Joseph Conrad’s novels because she hoped “they’ll affect my writing without my being bothered knowing how.” I wonder how much time she spent looking at the work of other artists, and, if she did, just how much of it rubbed off on her without her being bothered knowing how. Likely as not, she taught that chicken to walk backward without being bothered to know how either. It was her way.

Advertisement

This essay and selection of images are drawn from Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons, edited by Kelly Gerald, with an introduction by Barry Moser, to be published this month by Fantagraphics.