It has long been a commonplace that no region on earth embraced modern design more eagerly or fully than Scandinavia. During the early twentieth century, a host of reform-minded pioneers in the Nordic countries demonstrated how contemporary architecture and furnishings could both shape and respond to a changing society that was becoming closely attuned to the dignity of the common man.

But whereas we can now readily identify the woodsy humanism of Finland’s Alvar Aalto, the sublimated classicism of Sweden’s Gunnar Asplund, and the sprightly biomorphism of Denmark’s Arne Jacobsen, no single stylistic trait or big name leaps to mind when we think of Norwegian modernism. With only 5 million inhabitants, Norway is the least populous Scandinavian nation save Iceland, and its architectural output has been commensurately small. Furthermore, little has been written on Norwegian modernism outside the native language. Indeed, while Denmark, Finland, and Sweden have marketed their design cultures as a matter of foreign policy for nearly a century, Norway’s has remained relatively unknown (with the exception, perhaps, of Sverre Fehn, who had little international repute before he won the Pritzker Prize in 1997.)

During my first visit to Oslo last year, however, my curiosity was piqued when I noticed a dazzling little white-painted International-Style villa perched high above the harbor. It turned out to be the newly restored Ekeberg Restaurant of 1927–1931 by Lars Backer (1892–1930) that, as I soon learned, is hardly the city’s only early Modernist landmark. Along with F.S. Platou, Backer also designed the Horngården building of 1929–1930, Norway’s first attempt at anything approaching a skyscraper. This eight-story commercial structure contrasts terra-cotta-colored stucco flanks with a façade that alternates ribbon windows and horizontal bands of sage-green stucco. Backer’s designs would have attracted scant attention in Berlin at that time, but they now remind us how much such modest buildings can add to the texture of cities wise enough to preserve them.

In fact, there was an impressive amount of innovative construction in Oslo from around 1925 all the way up to the beginning of the Nazi occupation in 1940, as a revealing new exhibition at the Oslo Museum demonstrates. Curated by Linken Apall-Olsen and Lars Emil Hansen, “OsloFunkis”—a play on funksjonalisme (Functionalism), as International Style architecture is known throughout Scandinavia—celebrates a fascinating trove of built work that ought to inspire a reassessment of the Modernist canon, a project [suggested] (http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2012/jul/17/modern-architecture-dark-side/) by Jean-Louis Cohen’s recently published The Future of Architecture Since 1889 (though even his wide-ranging account includes no Norwegian design).

The rise of social democratic governments in post-World War I Scandinavia was prompted in part by progressive tendencies set in motion when Norway won its independence from Sweden in 1905 and Finland its from Russia in 1917. The Romantic Nationalism movement that shaped the arts throughout Scandinavia during the early twentieth century stressed local folkloric traditions, but it was less evident in Norway, where until the founding of the Norwegian Institute of Technology in Trondheim (1910) there had been no building-design school in the country. Before that, aspiring Norwegian architects were compelled to go abroad, principally to Germany, to receive their training. In 1929, however, avant-garde architecture in Norway received a tremendous boost with the founding of OBOS (Oslo Bolig Og Sparelag, the Oslo Housing and Savings Society), which financed huge new construction initiatives and is now the largest Nordic cooperative building association.

One of the most interesting Norwegian Functionalists was Arne Korsmo (1900–1968), who designed two celebrated private houses on the outskirts of Oslo. Korsmo and Sverre Aasland’s Villa Dammann of 1932 (now owned by the polar explorer Erling Kagge) contrasts cubic massing with a curved wing reminiscent of the perennially underrated German modernist Erich Mendelsohn, who with Rudolf Emil Jacobsen built Oslo’s propulsively curved Doblouggården department store of 1933.

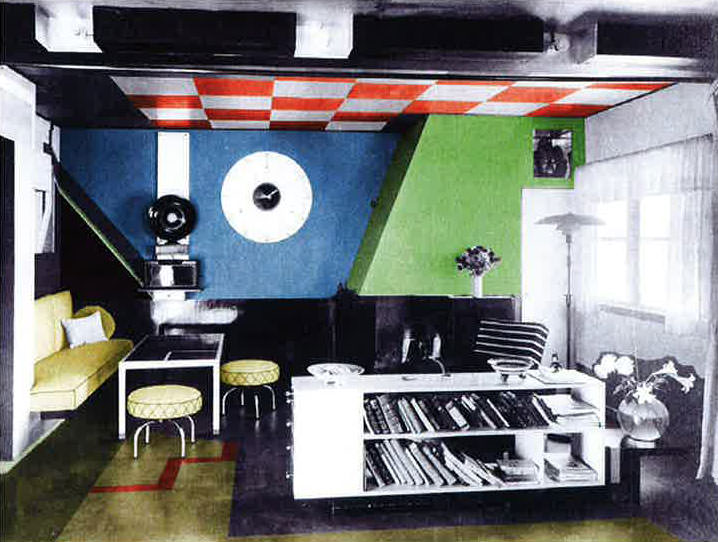

Villa Dammann departs from the cliché notion of monochromatic International Style architecture: with its stucco exteriors painted cerulean blue and terra cotta, it gives the lie to the canard that the Modern movement forbade color along with pattern and ornament. Though several early modernists—particularly Bruno Taut and, to some extent, Le Corbusier—used color on and inside their buildings, that fact has been largely forgotten because their projects were almost always photographed in black-and-white.

Korsmo’s Villa Stenersen of 1937–1938, commissioned by an art-collecting stockbroker who was Edvard Munch’s last great patron, sits on a hillside with breathtaking views of the Oslo Fjord. Open to the public, this four-story slab is faced with translucent glass brick and incorporates several ideas first advanced by Corbusier, including a supporting structure of reinforced-concrete pilotis and a curving drive-through garage tucked beneath the living quarters (ideas he employed at his Villa Savoye of 1929–1931 in France).

Advertisement

But Korsmo’s most influential contribution was his development of a detached-housing prototype that can still be seen all over Norway in countless adaptations of the original versions he built from 1929 onward (including one for himself adjacent to the University of Oslo campus). Based on traditional Nordic domestic architecture, these two-story, two-family houses are square in plan, with the ground floor faced in light-painted stucco and the second clad in horizontal wood siding beneath a gently pitched, slightly overhanging pyramidal roof.

Built on small garden plots, with each family occupying a full story, these neat, compact houses are free of extraneous detailing but feel neither aggressively modern nor retrogressively conservative. Rationally conceived, sensibly proportioned, and expertly crafted, Korsmo’s sturdy but graceful dwellings exude a low-key charm that seems to embody the Norwegian national ethos. When construction resumed after the liberation of Norway in 1945, the Functionalist idiom was taken for granted as the lingua franca of the nation’s architecture, but with no dominant figure on a par with the big-name designers of mid-century Denmark and Finland, Norwegian Modernism has only lately been rediscovered.

What Oslo needs now is a comprehensive English-language guidebook to its estimable Functionalist heritage. Such a publication would doubtless spur cultural tourism among the international brigade of design enthusiasts one encounters at Modernist landmarks all over the world. At the forefront of such a compendium would correctly be Eyvind Mostue and Ole Lind Schistad’s Ingierstrand beach resort of 1931–1934, two miles southeast of the city, on the shores of Oslo Fjord.

When the waters close to the city’s inner harbor became too polluted for swimming, the local government—attuned to new notions of physical fitness as a key to public health and well-being—sponsored this day resort for the masses at safe remove from the capital, but still near enough to be reached by bicycle. Comprising a sleekly low-slung, flat-roofed restaurant pavilion with a circular outdoor dance floor raised atop a concrete mushroom column, the resort overlooks the water and features a dynamically cantilevered thirty-foot-high concrete diving platform. This delightful ensemble, sensitively situated on the rockbound coast, was strongly influenced by Asplund’s Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, which expressed a structural lightness and decorative playfulness that came to typify progressive Scandinavian design.

By the 1970s Ingierstrand had fallen into disrepair, but happily this neglected masterwork is now undergoing a painstaking restoration and will reopen to the public next spring—a triumph of Modernist preservation on a par with the recent rescue of Jan Duiker and Bernard Bijvoet’s Zonnestraal Sanatorium of 1926–1931 in Holland. Though diametrically different in function, both schemes show the extent to which enlightened social democracies saw Modernism not merely as a matter of style but as a way to build a better world. Along with the revelatory “OsloFunkis,” the impending return of Ingierstrand to its rightful place among the gems of European Modernism is certain to ratify Norway’s own vital part in this enterprise.

“OsloFunkis” is on view at the Oslo Museum, Oslo, Norway from November 13, 2012 until October 20, 2013.