Recently, the British pianist Stephen Hough reported on his blog that he had made “The most exciting musical discovery of [his] life: Tchaikovsky’s wrong note finally corrected.” The article questioned a note in Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, a large-scale, virtuosic piece that makes striking use of Russian folk themes. At the start of the concerto’s slow movement, the flute plays a phrase that consists of the notes A-flat, E-flat, F, A-flat.

In his article, Hough admits that the F has always bothered him, because when the piano restates the melody a moment later, the theme has a B-flat instead of an F (A-flat, E-flat, B-flat, A-flat).

The B-flat gives the melody phrase an entirely different shape and this shape persists in nearly every other appearance of the theme. What if the F at the start of the movement was a mistake, and B-flat had been intended?

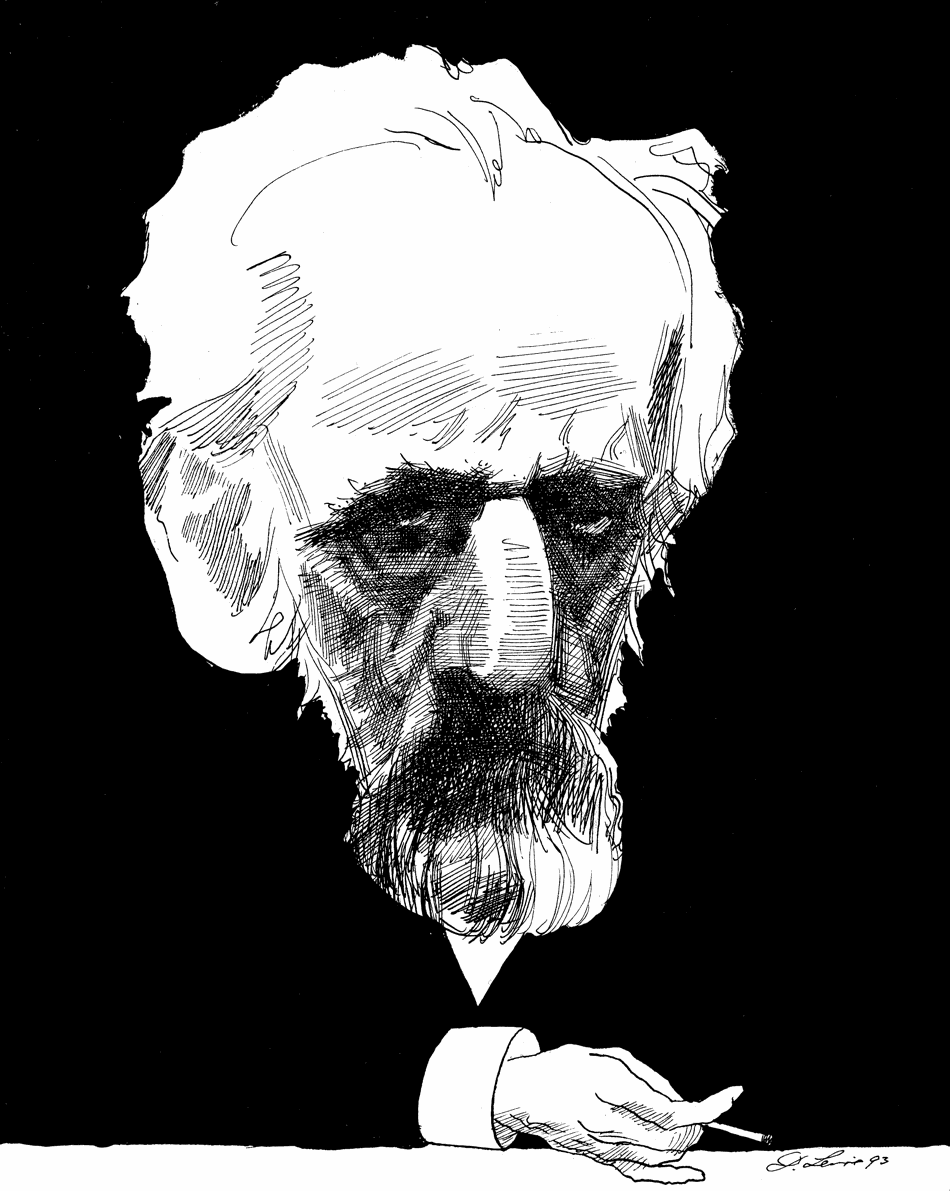

As I read Hough’s piece I became anxious. I think this F is a charming anomaly, an instance of inexplicable compositional inspiration and lovely asymmetry that greatness often displays. I feel moved when I hear this alternation between the tender innocence of the F and the heightened expressivity of the following B-flat. Still, Hough had evidence to support his hunch: he had come across a manuscript of the work held in a library in Berlin. In that score, this potentially troublesome note is crossed out in blue pencil, and corrected, in script that seemed to resemble Tchaikovsky’s, to a B-flat.

The manuscript of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto consulted by Hough, housed in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. The F, changed in blue pencil to a B-flat, appears in the fifth bar of the Flute part.

In a subsequent post, “Stop press: a different mistake but a more convincing solution in Tchaikovsky’s concerto,” Hough wrote that it had come to light that none of the manuscript was in Tchaikovsky’s hand. It is not clear who changed the note. But we do know that a copyist produced the score for Hans von Bülow, the great pianist and conductor, who premiered Tchaikovsky’s piano concerto in Boston in 1875. Hough then proposed that the F natural was a copyist’s error, later corrected by von Bülow, and believes that von Bülow would not have made such a correction without consulting Tchaikovsky.

Reading this, I thought that Tchaikovsky’s autograph scores of the concerto and the score that he used when conducting, all housed in Russia, might have the definitive answer. I contacted the Tchaikovsky expert Polina Vaydman, the senior researcher at the Tchaikovsky State Museum in Klin. She has written several books on the subject of Tchaikovsky’s compositions and manuscripts, and is currently involved in the preparation of a critical edition of the first piano concerto.

In an exchange, she confirmed that a copyist in Moscow prepared the score now housed in Berlin for von Bülow in the summer of 1875. “We think,” she said, “that Tchaikovsky did not see this particular copy, as this score contains no markings in his hand whatsoever.”

In Vaydman’s opinion, the idea that this F would be wrong is typical of a European view that repetitions of a theme should match—an idea that is, strictly speaking, in accordance with the elementary laws of music theory. But here Tchaikovsky is not following this principle of repetition. Instead, he chooses to present two micro-variants of the melody, a bit like a forked path that later rejoins. This variability of recurring thematic material is typical of Russian vocal folklore. Tchaikovsky often used this method as a compositional strategy both for expressive and structural purposes, enabling him to give the repetitions a sense of development, thus keeping listeners’ interest from flagging.

So there is no reason to think that the B-flat correction on the Berlin manuscript is Tchaikovsky’s rather than von Bülow’s. Indeed, Vaydman later sent me an excerpt from a letter that von Bülow wrote in 1879 to Karl Klindworth, the German pianist, composer and music publisher, and a fellow pupil of Liszt. Von Bülow asks him, “Is the flute in bar 5, sixth eighth-note F (instead of B-flat, which I would like to have) in the second movement…not a mistake?” The F, in other words, seems to have irritated von Bülow, but there’s no evidence that Tchaikovsky was bothered by it.

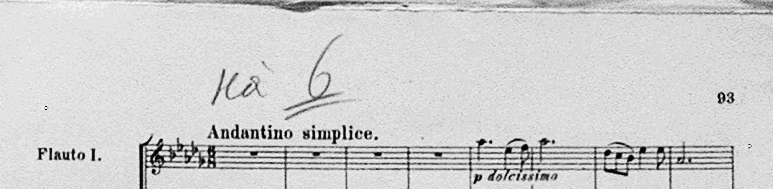

Tchaikovsky’s personal conducting score of the First Piano Concerto, which he used during his last public concert in 1893. Note his own pencil marking “На 6” (in 6) at the top left of the page. The F in the flute part is unchanged. According to the Tchaikovsky expert Polina Vaydman, all known manuscript sources contain this F.

Performers concerned with how to interpret a piece often pore over manuscripts and early editions, trying to to sweep away the cobwebs of later editorial interventions and gain a better understanding of a composition. This is one of the ways we try to better inform our own performances. A great satisfaction can be derived from this process, wondering how a particular note came to be, what earlier form it might have taken, what the composer may have intended it to evoke.

Advertisement

To me, the lovely, asymmetrical F is redolent of the unpaved country roads of Tchaikovsky’s Russia. The symmetrical repetition of the B-flat, on the other hand, suggests the cultivated cities of von Bülow’s Europe.

In future performances, I await this F with renewed expectations: a whole additional set of associations, discussions, and emotions.

Historic Performances of the First Piano Concerto