In 1938, Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke to an encampment of grizzled Civil War veterans who had returned to Gettysburg for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the battle. “It seldom helps to wonder how a statesman of one generation would surmount the crisis of another,” he warned. But then he did just that, using Lincoln’s language to inspire a new generation of Americans “to preserve under the changing conditions of each generation a people’s government for the people’s good.”

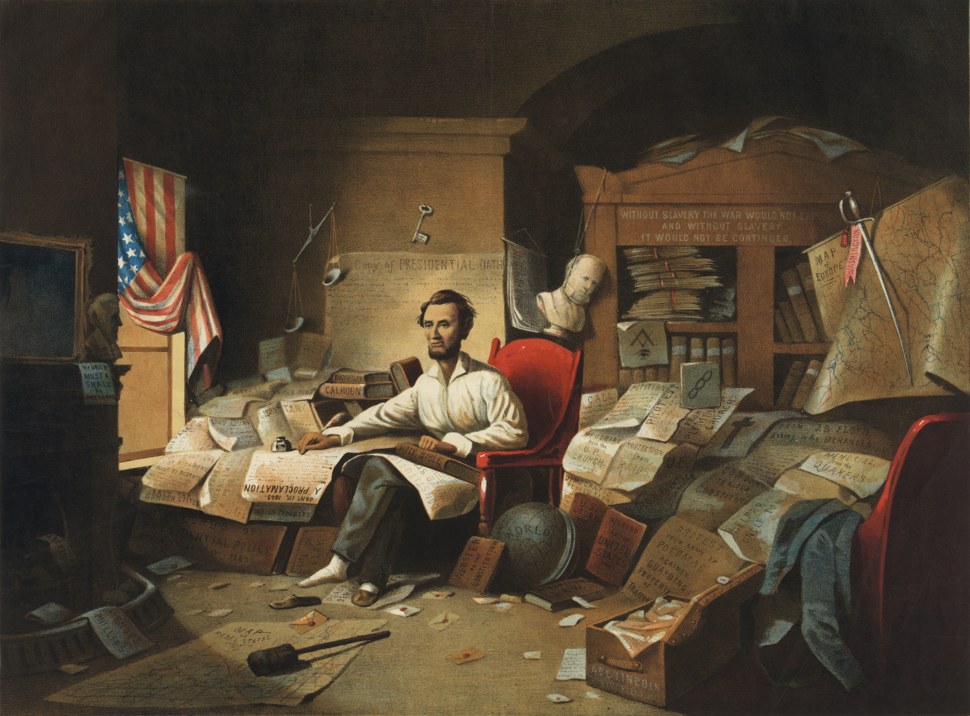

We can’t help ourselves from returning over and over again to the words of a president who towers above the others—or even purchasing his manuscripts outright, as if to keep them out of harm’s way. J.P. Morgan placed his Lincoln materials in a vault, deep below his Renaissance palazzo on Madison Avenue. More recently, the financiers Richard Gilder and Lewis E. Lehrman have acquired a substantial trove of Lincolniana, impressive for its scope, and for the fact that such a collection could be assembled at all, so late in the game. The best parts of these private holdings—along with choice additions from several museums and libraries— have now been put on display in Lincoln Speaks: Words That Transformed a Nation at the Morgan Library and Museum.

It is clear that writing was a form of self-therapy for Lincoln, and before he could save the nation, he needed to find the right words, to save himself. His stepmother remembered that as a child, Lincoln would laboriously write out the words he had heard adults use, and grow frustrated when he did not understand them. His comprehension grew quickly, in part because of the books he was able to find on a frontier that was not as remote as his later myth-makers would have us believe. In the exhibition, a very fine 1807 edition of Shakespeare, Lincoln’s own copy, sits open to his favorite play (Macbeth).

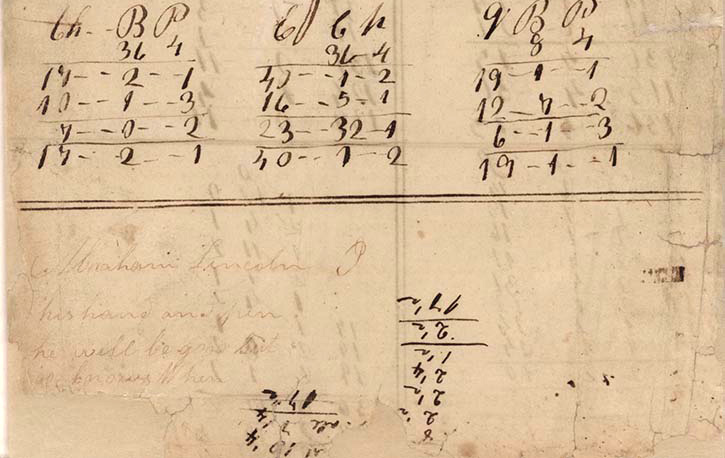

But Lincoln was hardly Shakespearean at first—except perhaps in his own kind of low comedy. The show opens with the only document borrowed from the vast Lincoln collection at the Library of Congress, an item from his childhood, showing him practicing his handwriting, and mischievously scrawling doggerel: “Abraham Lincoln, his hand and pen, he will be good, but God knows when.” Later in his youth, a tortured letter he wrote to a romantic prospect reveals him asking her to marry him, but then recommending that she say no. It is agonizing to read, as it surely was to write (the ink smudges are telling). That same letter suggests Lincoln’s wildness in other ways, as well, bragging that “I’ve never been to church yet, and probably shall not be soon.” It is the work of a young man who had some growing up to do.

Once he mastered himself, he discovered he could bring along others. Another document in the show, J.P. Morgan’s copy of a note Lincoln wrote to himself during the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, reveals that he considered the art of persuasion crucial to his political career: “In this age, and this country, public sentiment is everything—With it, nothing can fail, against it, nothing can succeed.” By that pivotal year, well represented here, he had found his voice, and a national audience.

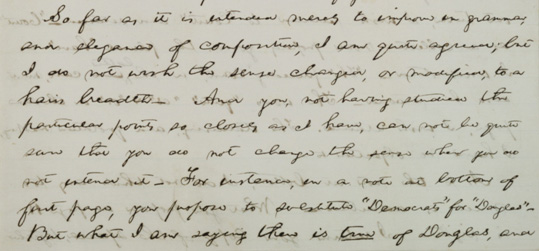

Maintaining it required a steely discipline, and some testy exchanges with the editors he needed to get his writing to a national audience. Lincoln is often remembered for his modesty, but it is refreshing to see the letter he wrote to a New York editor who had presumed to alter a few of Lincoln’s sentences (from his Cooper Union Address) for publication. Lincoln responded tersely that he would not permit any changes to “a hair’s breadth,” because he knew much more than the editor did about the subject.

After his election, very different kinds of writing were needed, from the placating words of the first inaugural to the military commands essential for the defense of Washington after his entreaties had failed. There is a shrill order to a general in the spring of 1861, when it was unclear that Washington could be saved, admitting that “I am alarmed” and demanding that five regiments be sent quickly to Washington. This is displayed effectively alongside a calm telegram to Ulysses Grant in 1864, when the impact of Grant’s strategy of total war had become clear: “Have just read your despatch of 1 p.m. yesterday. I begin to see it. You will succeed. God bless you all.” That terseness may have been a measure of fiscal discipline—telegrams charged by the word—but it also emanates the power Lincoln had discovered, to say more with less.

Advertisement

At other times, Lincoln’s voice was not restrained at all. He refuses to extend clemency to a slave-trader facing execution, urging him to “refer himself alone to the mercy of the Common God and Father of all men,” having relinquished “all expectation of pardon by Human Authority.” He describes, with exhilaration, the effect on the Confederates of seeing a mighty armed force of African-Americans: “The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once.” In a dispatch to Andrew Johnson, then the military commander of Tennessee, Lincoln writes, “it cannot be known who is next to occupy the position I now hold, or what he will do.” That successor, of course, would be Johnson himself.

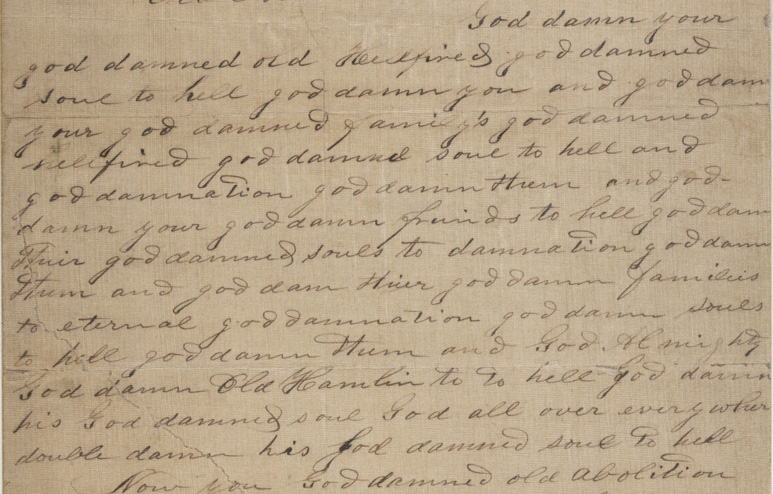

Some of the most moving documents are his letters to and from constituents. One of them is frightening—an enraged letter to “Old Abe Lincoln” from Pete Muggins, of Fillmore, Louisiana, that should give pause to anyone crazy enough to run for president. It begins “God damn your god damned old Hellfired god damned soul to hell god damn you,” and continues through about a dozen more “god damns” before finding the noun it was looking for, “son of a bitch.” For his part, Lincoln wrote letters of exquisite tenderness—one to a young man who had been rejected from Harvard, another to a woman whose father had been killed and who was suffering from acute depression. Lincoln was familiar with that topic, as he revealed for a split second, when he let down his mask to console her and admitted that he understood what she was going through (“I have had experience enough to know what I say”). Unlike so many efforts to politicize suffering, this feels authentic.

It might seem that Lincoln’s long argument to impose order through language failed—a speech not included here, his final one, announced plans to give the vote to black soldiers, and sent John Wilkes Booth over the brink. It would take precisely a century before voting rights would be secure for all Americans, as the film Selma reminds us. It is not entirely clear that Lincoln could have accelerated that glacial pace, even if he had lived. There are few African-American voices in the exhibition, but they are powerful, and put everything else into perspective.

In 1909, Booker T. Washington was asked to speak on the centennial of Lincoln’s birth. He began with a simple statement so eloquent that it stayed with me long after I left the Morgan and went back out into the twenty-first century, on the same night that President Obama was delivering his sixth State of the Union. A former slave, Washington addressed his mostly white auditors, and said, “You ask that which he found a piece of property and turned into a free American citizen to speak to you tonight on Abraham Lincoln.” Not “you asked him,” but “you asked that ….” It is the kind of precise writing Lincoln strove for, up to the final punctuation mark.

Lincoln Speaks: Words That Transformed a Nation is at the Morgan Library through June 7, 2015.