It happened that on the day the great saxophonist and composer Ornette Coleman died I was watching a preview of a recently salvaged film by Sydney Pollack of the making of Aretha Franklin’s Amazing Grace. The album was recorded live at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles, the city where, in the late 1950s, Ornette and his collaborators, Charlie Haden (bass), Don Cherry (trumpet), and Ed Blackwell or Billy Higgins (drums) had formed the quartet that would soon declare the shape of jazz to come. The idea for Amazing Grace was that Aretha would record an album of the gospel music she’d grown up hearing and singing in her father’s church in Detroit. This was in 1972. John Coltrane had died in 1967, Albert Ayler—the tenor saxophonist who, along with Ornette, had played at Coltrane’s funeral—in 1970. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been dead for four years. The unifying grace of the civil rights era had given way to the fractured militancy of Black Power and revolutionary struggle.

The Southern California Community Choir march into the church with the quasi-military precision associated with the Panthers or the Nation of Islam. They’re dressed in the kind of silver, intergalactic costumes that locate the promised land in an Afro-futurist vision of outer space. But once the singing starts they reach far back into history, to the foundational elements of black American music: spirituals and gospel.

Tomorrow is the question, Ornette declared. But his answers contained big chunks of yesterday. His most famous composition, “Lonely Woman,” is a dirge so mournful it seems to lament its own existence—in a succession of increasingly exuberant proclamations. If there is melancholy in the titular question “When Will the Blues Leave?” the answer is a joyously hopeful “Never!” In Visions of Jazz Gary Giddins quotes drummer Shelly Manne saying in 1959 that Coleman’s sound was “like a person crying…or a person laughing.” That contradiction—the contradiction that is not a contradiction—lies at the heart of so much African-American music.

One of the things that the most extreme first-generation of free players such as Ayler and Pharoah Sanders shared with Ornette was the experience of playing R&B in their journeyman years. The open-throated, gutbucket sound came as readily to them as breathing. This was every bit as important—and as present in their playing—as the tradition-shattering qualities that provoked such fierce hostility or reverence. Their musical apprenticeship earthed them and explains why free jazz was able to take root. Which makes it extraordinary that Charles Mingus—to say nothing of Roy Eldridge and Miles Davis—refused to hear what seems now to be a defining aspect of Ornette’s sound. Surely Mingus, of all people, should have responded to the honk and holler, the cry and call. Miles’s hostility was probably due, in some measure, to his highly developed sense of rivalry or threat. Unblemished by any such feelings, Coltrane was an immediate convert and an eager pupil.

Another irony about the way R&B underpinned such radical experimentation is that R&B has since become the blandest musical pap on the planet. Listening to contemporary R&B is about as challenging as listening to the Eagles. Ornette’s early recordings for Atlantic (collected in the indispensable box set Beauty Is a Rare Thing), on the other hand, still sound far-out—and as drenched in blues and roots as a Mingus album.

Ah, but how old it’s become, this still new-sounding music! In March I went to see Oliver Lake (seventy-two), Andrew Cyrille (seventy-five), and Reggie Workman (seventy-seven) at the Village Vanguard in New York—a legendary venue that has not been at the vanguard of anything for at least thirty years. With the best will in the world you couldn’t say it was a great gig, though it’s wonderful, of course, that Workman (who played with Coltrane) is still a working man. But you can’t play their kind of music without taking the roof off the place. That’s what Ornette’s quartet did when they came east, to New York, in 1959. They didn’t just take the roof off the 5 Spot; they took the roof off the idea of the roof and, as a result, left jazz exposed to the elements. In the following decade jazz became torrential.

As with so many revolutionary happenings this one began with a small cabal of initiates bonding together while the soon-to-be-shaken world looked and listened elsewhere. I find it incredibly moving to think of Cherry, Haden, and Blackwell (or Higgins) gathering at Ornette’s place in Los Angeles to immerse themselves in his musical philosophy, playing a new kind of music in which the song’s form could be dictated by collectively improvised melodic lines, rather than harmonic progressions. They’re all dead now. Ornette outlived everyone in Old and New Dreams, the band of his alumni (including Dewey Redman on tenor) devoted to exploring his music, its legacy and potential.

Advertisement

It hardly needs emphasizing that the desire for freedom in jazz is bound up with the larger dreams of freedom itself. This, obviously, is a vast topic, one that cries out for treatment in a full-scale documentary film (especially since the relevant episode from Ken Burns’s otherwise magnificent series was so cursory). To simplify things let’s stick to a few obvious examples.

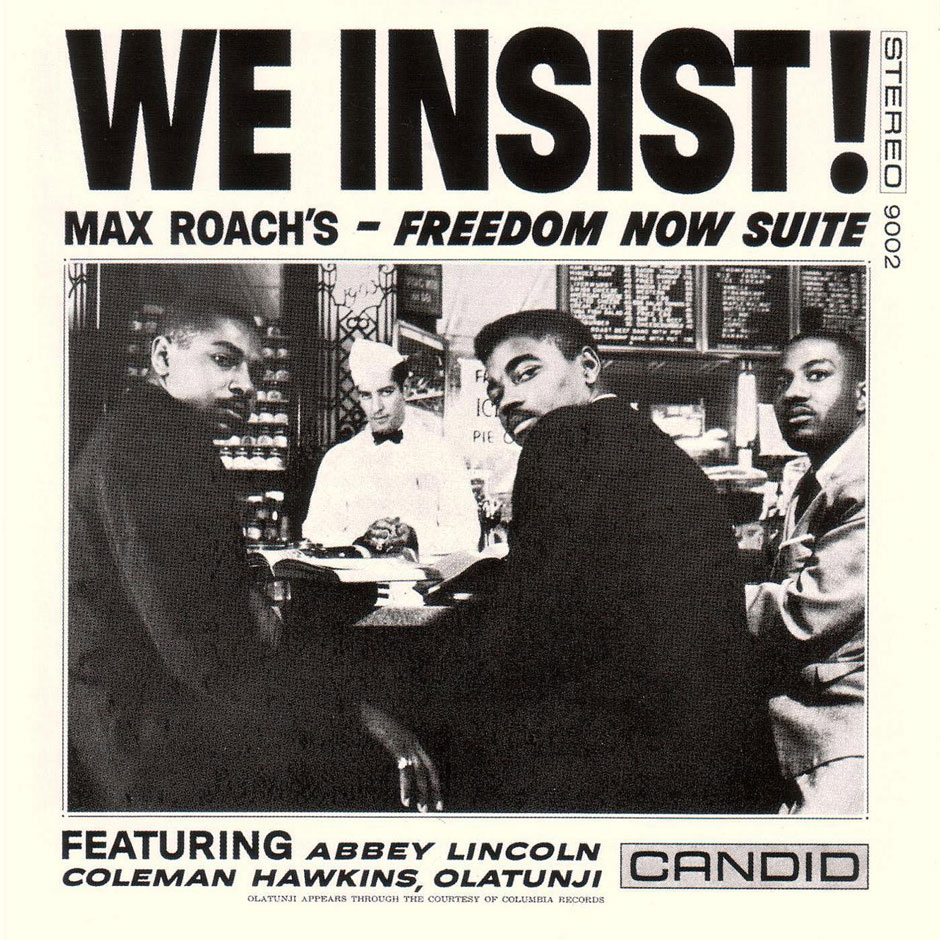

Sonny Rollins’s Freedom Suite (1958) was a pre-Coleman declaration of musical and political liberation—but there was no explicit statement of this conflation on the album. And the music on offer was still sufficiently conservative for a cover version of a Noel Coward tune to sit happily alongside the ambitious title piece. Recorded two years later, We Insist! Freedom Now Suite by Max Roach (who played drums on the Rollins album) was explicitly interventionist, with its cover featuring a news photograph of a lunch counter sit-in. Even after the smaller-scale detonations of Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959) and Change of the Century (1960), his album Free Jazz (1961) was a musically incendiary event, but Ornette tended to play down the connection between his musical project and the larger social turbulence of which it might have seemed a product and expression. Hereafter, however, “free” playing became so ideologically freighted that the struggle to gain acceptance for this music—the purpose and attraction of which lay, to a considerable degree, in the way that it was audibly unacceptable to a significant portion of the population—became part of a larger struggle.

The alliance of revolutionary politics and music reached a rhetorical extreme with Archie Shepp’s famous claim, in 1968, that his saxophone was “like a machine gun in the hands of the Viet Cong.” Theoretically it may have been possible for musicians to record an album fully pledged to the idiom of free jazz without committing to the politics of Black identity—but not in America. Only after a sabbatical in Europe—symbolically if belatedly represented by those Nice Guys from the Art Ensemble of Chicago, sitting outside a Paris café on the cover of the eponymous album—could free jazz become a kind of equal-opportunity employer in reverse, whereupon it was re-imported to the US, minus the ideological trappings that were also part of its foundation.

So when Pharoah Sanders cries out “You’ve Got To Have Freedom” on any number of recorded versions of that song he’s both celebrating what the music has liberated itself from and what African Americans have struggled—and continue to struggle—for. But he’s also declaring his freedom to keep working, to keep performing “You’ve Got To Have Freedom” wherever and whenever he can get a gig.

Enlarging the question about free playing: When did it begin, this longing for freedom of which Ornette’s music is the undying expression? You could say that it began with the founding fathers as long as you factor in that the American project of freedom and equality for all was in its original intent predicated on a percentage of the population being denied any freedom. Right from the start there was a cage in which the dream of freedom would begin its long incubation.

It’s strange how listening to early Ornette—as I’m listening to him now—is to surrender to the closing claim of that great chronicle of the so-called jazz age: to be borne back ceaselessly into the past. Specifically, I find myself being drawn back to 1843, to a lecture by James McCune Smith entitled “The Destiny of the People of Color,” part of which is quoted by David Brion Davis in The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Emancipation. As Davis puts it, McCune Smith’s lecture concludes “with a prophecy that the African Americans’ struggle for liberty would lead to a revolutionary contribution to American culture”:

We have already, even from the depths of slavery, furnished the only music which the country has yet produced. We are also destined to write the poetry of the nation; for as real poetry gushes forth from minds embued with a lofty perception of the truth, so our faculties, enlarged in the intellectual struggle for liberty, will necessarily become fired with glimpses at the glorious and the true, and will weave their inspiration into song.