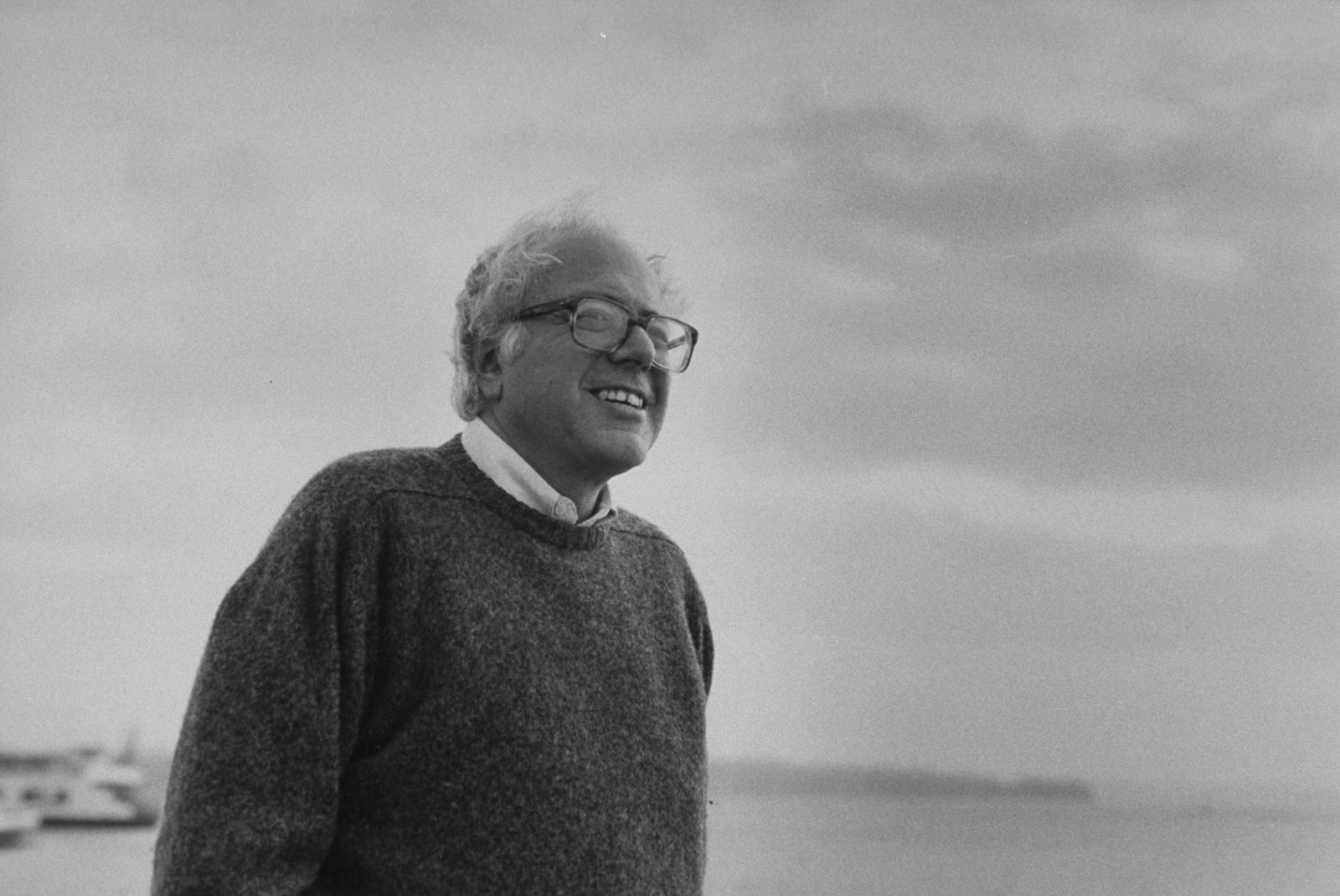

In 2003 I wrote in my The New Ruthless Economy that one of the great imponderables of the twenty-first century was how long it would take for the deteriorating economic circumstances of most Americans to become a dominant political issue. It has taken over ten years but it is now happening, and its most dramatic manifestation to date is the rise of Bernie Sanders. While many political commentators seem to have concluded that Hillary Clinton is the presumptive Democratic nominee, polls taken as recently as the third week of December show Sanders to be ahead by more than ten points in New Hampshire and within single-figure striking distance of her in Iowa, the other early primary state.

Though he continues to receive far less attention in the national media than Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump, Sanders is posing a powerful challenge not only to the Democratic establishment aligned with Hillary Clinton, but also the school of thought that assumes that the Democrats need an establishment candidate like Clinton to run a viable campaign for president. Why this should be happening right now is a mystery for historians to unravel. It could be the delayed effect of the Great Recession of 2007-2008, or of economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez’s unmasking of the vast concentration of wealth among the top 1 percent and the 0.1 percent of Americans, or just the cumulative effect of years of disappointment for many American workers.

Such mass progressive awakenings have happened before. I remember taking part in antiwar demonstrations on the East and West coasts in the Fall and Winter of 1967–1968. I noticed that significant numbers of solid middle-class citizens were joining in, sometimes with strollers, children, and dogs in tow. I felt at the time that this was the writing on the wall for Lyndon Johnson, as indeed it turned out to be. We may yet see such a shift away from Hillary Clinton, despite her strong performance in the recent debates and her recent recovery in the polls.

If it happens, it will owe in large part to Sanders’s unusual, if not unique, political identity. Consider the mix of political labels being attached to him, some by Sanders himself: liberal, left-liberal, progressive, pragmatist, radical, independent, socialist, and democratic socialist. Sanders’s straight talk about the growing inequalities of income and wealth in America has been much written about, notably in a long profile of him in The New Yorker in October. But most of this writing has been of the campaign trail genre, and has not gotten very far in sorting out the strands of radicalism that have come together in Sanders’s run for the presidency and that have attracted large numbers of Americans dissatisfied with their deteriorating economic circumstances and with the politics that has helped create them.

Sanders is unusual because he brings together three kinds of radicalism, each with very different roots. First is Sanders’s commitment to bringing the progressive ideas of Scandinavian social democracy to the United States, including free and universal health care, free higher education at state colleges and universities, mandatory maternity and sick leave benefits, and higher taxes on higher incomes. In American political history you have to go back to Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society or even to the early New Deal to find anything comparable.

The second strand of Sanders’s radicalism is his excoriating account of contemporary American capitalism, and with this he neither looks nor sounds like a consensus-minded Scandinavian social democrat. Here Sanders is willing to name and denounce the new economic royalists—what he calls collectively the “billionaire class”—in a way that Hillary Clinton, who has relied heavily on their financial backing, has not. These include the leading Wall Street banks and their lobbyists; the energy, health care, pharmaceutical, and defense industries; and the actual billionaires deploying their wealth on behalf of the far right, foremost among them the Koch brothers, the Walton family of Walmart, and the real estate tycoon Sheldon Adelson.

From these great concentrations of wealth and power, Sanders argues, derive multiple injustices: the corrupting of electoral and legislative politics with the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling; the steady erosion of the American middle class, which has suffered stagnating income and declining benefits, even as corporations return to profitability and enjoy historically low interest rates; and the emergence of an American workplace where most employees are putting in longer hours, earning less, and suffering from less job security than ever before.

Sanders can support these claims with substantial bodies of empirical data and research. There are the monthly figures put out by the government’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which show a steady decline in real hourly and weekly earnings of most working Americans since the 1970s. There is the work of the French economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez documenting a growing and overwhelming concentration of income and wealth in the US in the hands of the top 1 percent—and especially the top 0.1 percent—of taxpayers. There is also the research of Jacob Hacker of Yale, showing how the disposable income of middle-income Americans has been further eroded by health care and pension costs dumped on them by their corporate employers, what Hacker calls the Great Risk Shift.

Advertisement

But the challenge for Sanders is not the arguments themselves, which are widely acknowledged (Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century was a runaway bestseller last year). The challenge is how to organize those who have suffered in the harsh new economy into a viable political force. In the 1930s and the succeeding decades many of those facing hardship could benefit from the support and solidarity of big labor unions and the Democrats’ big-city political machines. In our own times these networks are largely gone. Those being laid off, downsized, reengineered, or outsourced today are, in comparison with their grandparents and great-grandparents, far more likely to find themselves isolated and alone, especially those from middle-income families, who may be facing a drastic and very visible loss of class identity.

It is here that the third and perhaps least understood strand of Sanders’s radicalism comes into play: his ability to organize a previously unrecognized constituency—one that embraces the shrinking middle class, both white- and blue-collar, the working and non-working poor, as well as young, first-time voters with large student-loan debts. One thing that comes over strongly in interviews of those attending Sanders rallies is their sense that they are no longer alone, that they’re joining with thousands who are in much the same predicament as they are, and that together they can change things for the better.

Sanders’s success in bringing these people together comes from his grounding, as a student at the University of Chicago in the early 1960s, in the grass-roots politics of Saul Alinsky (1909–1972), the founder of modern American community organizing. Alinsky’s crucial insight was that people at the bottom of the system could fight for local political and economic power by forming alliances with sympathetic community groups sharing many of their interests. From the late 1930s through the 1960s, Alinsky focused on the black ghettoes and white working-class districts of Chicago, Rochester, Buffalo, Oakland, and many other cities. His greatest success—and one of the best examples of his methods at work—was his 1939 campaign to unionize the Armour Company’s Back of the Yards meat packing plant in Chicago.

In the late 1930s, working conditions at the Armour plant still evoked the world of Upton Sinclair: an immigrant workforce toiled long hours for poverty wages, in unsanitary and unsafe conditions. With Chicago run by a corrupt political machine, Alinsky took the lead in mobilizing every constituency he could in the local community against Armour—including the churches and especially the Catholic Church, labor unions, neighborhood groups, athletic clubs, and small businesses.

He brought in John L. Lewis of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) to advise him, and after a huge mass demonstration in July 1939, Armour agreed to recognize the union. In a 1999 PBS documentary, Ed Chambers, who was Alinsky’s successor as Director of the Industrial Areas Foundation, described the tactics that had proven so successful—and that would be repeated in many of Alinsky’s postwar campaigns: “All change comes about as a result of pressure or threats. But you can’t get social change or social justice without confronting it. Because if you are a ‘have not,’ ‘the haves’ never give you anything that’s real.”

Alinksy is no longer a reference point in contemporary American politics, although his work and influence features in the CVs of both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. In a 2007 New Republic profile, Ryan Lizza describes the young Obama’s training as an Alinskian community organizer in 1980s Chicago, though Lizza noted that Obama as a presidential candidate-in-the-making was already distancing himself from this past, omitting all mention of Alinsky in his campaign biography, The Audacity of Hope. For her part, Clinton titled her 1969 BA thesis at Wellesley College “There is Only the Fight…”: An Analysis of the Alinsky Model, something she has not cared to mention in recent campaigning.

But it is Sanders who has gone on to put Alinskian methods into practice as both a politician in Vermont and a candidate for president. In a November interview with NPR, Sanders described how his work as a community organizer as a student at the University of Chicago “did a lot to influence the politics I now have.” In fact, Sanders was chair of CORE’s (Congress on Racial Equality) social action committee at the university at a time when the organization, advised by Alinsky, was leading the campaign against segregation in Chicago schools and housing. CORE and its student supporters were fighting the university itself, which upheld segregation through a policy of purchasing vacant homes in its neighborhood to prevent them from being purchased by African Americans. In 1962, Sanders organized a sit-in at the president’s office to protest the university housing policies; the following year, he was arrested while demonstrating against segregation in the Chicago schools.

Advertisement

Two decades later, Sanders’s remarkable campaign for Mayor of Burlington, Vermont as an independent was another illuminating case history of successful Alinskian campaigning at the grassroots, adapted from its Chicago origins to the more tranquil setting of Vermont. Sanders followed Alinsky’s cardinal rule of taking on the city’s dominant business interests and their allies in City Hall with a program that was, for Burlington, radical and progressive: curbing real estate development at the city center and providing ample public space there, especially on the waterfront of Lake Champlain; building affordable housing; keeping out the mega-retailers and creating neighborhood associations as participants in city planning decisions. To achieve this Sanders put together an all-embracing, Alinskian coalition of women’s groups, unions, neighborhood activists, environmentalists, even the police patrolman’s association, all of whom saw him as someone who could deliver on his pledge to make Burlington a more affordable and civilized place to live.

There are big differences between Burlington, with a population of 42,000, and the United States, with a population of nearly 320 million. Alinsky himself never tried to reproduce his approach on a national scale. But in Alinsky’s time there were no social media, whose potential Sanders, like the Obama campaigns in 2008 and 2012, has deftly exploited. And unlike the president, Sanders has also used social media to rally people behind a truly radical message. Not only has he formed alliances with sympathetic community groups like labor unions, environmental organizations, immigrant advocacy groups, and public sector workers; he has also been able to rely on these groups’ own considerable presence on social media to reach voters.

These efforts may be less attention-getting than Trump’s, but they have proven highly effective in building a strong base of supporters. The Sanders campaign has now drawn more than 2.2 million individual donations in 2015, surpassing even Obama’s record for the number of donations to a presidential candidate in a single year. In the third quarter, he raised four times as much money as Clinton from donors contributing $200 or less.

The columnist Mark Shields has pointed out on PBS’s Newshour that it was no mean feat for Sanders to attract an audience of 27,500 in Los Angeles in August, a city where, in Shields’s words, the typical campaign event is a party at Steven Spielberg’s house hosted by George Clooney. This was an event at which Sanders said, to thunderous applause,

There is something profoundly wrong when one family, the owners of Walmart, own more wealth than the bottom 40 percent of the American people. This is an economy which is rigged, which is designed to benefit the people on top, and we are going to create an economy which works for all people.

Sanders has significant weaknesses. His poll numbers have been much lower in the south, where he is far less known. They show Hillary Clinton enjoying strong support among African Americans, who favor her over Sanders by 5–1 or more. But it is surely patronizing to African-Americans to portray them as locked in an unending embrace with the Clintons, impervious to Hillary Clinton’s reliance on big corporate donors, her weaknesses as a candidate, which are still considerable, and the shifting winds of the campaign as it unfolds. Until now, Sanders has largely avoided direct criticism of Clinton. The big question is whether he will extend his critique of the billionaire class and their corrupting political power to what I’ll call the Clinton system. That system will be the subject of a second article.