The eighty-four-year-old sculptor Arthur Kern owes his sudden mini-celebrity to the New Orleans infectious disease doctor Brobson Lutz. The two men are, by all appearances, opposites. Dr. Lutz, who lives in Tennessee Williams’s old mansion in the French Quarter, is well-known around town for his sartorial dash and trademark eyeglasses—Lifesavers from Morgenthal Frederics in Manhattan, oval frames with a jaunty peaked bridge—of which he owns more than a dozen pairs, each a different electric color. Kern, according to the title of his new show at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art—“Arthur Kern: The Surreal World of a Reclusive Sculptor”—is a recluse, though this claim is not entirely persuasive.

Between 1967 and 1996 Kern taught art classes at the University of Southwest Louisiana and Tulane. He has been married for sixty years and has three daughters. Recently he even invited a reporter from The New York Times into his New Orleans home to discuss his aversion to discussing himself. But he socializes so rarely that his former students long believed he was dead. They assumed he fell victim to the decades of exposure to industrial fumes in his studio. He sculpts with polyester resin, which is most commonly used in the manufacture of boat hulls.

With the exception of a minor show in Lafayette, Louisiana, more than a decade ago, Kern has not before now publicly displayed or sold his sculpture. He might never have were it not for Dr. Lutz, who happens to know Kern’s cousin. Lutz noticed a few photographs of Kern’s work lying on the cousin’s coffee table. He shared the photographs with another friend, the writer and part-time New Orleans resident John Berendt who, judging by Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, has a keen radar for eccentrics and misanthropes. The result is a mesmerizing show at the Ogden that is at the same time a debut and a retrospective. The museum’s emphasis on Kern’s unusual personal story, as appealing as it is, seems misplaced when one is confronted with his work, which is strange enough to survive any creation myth.

The sculptures, created between 1968 and 2008, are unsettling, haunting, grotesque, sublime. They fall into three categories, each occupying one of the exhibition spaces on the Ogden’s top floor. The smaller room contains a series of nudes and busts. In these sculptures the polyester resin assumes the fine, bone-white quality of ceramic. Beautiful female figures are splayed open like the mermaid figureheads on the bows of galleons, though they are rarely spared some physical deformity. In Elegy, a woman’s chest is bisected by scar tissue; a bird flies out of her forehead. Persona is a visitation from hell: a bald woman draped in a mourning shroud, her face covered by a lifelike mask. The mask’s eyelids droop like melting wax. The eye sockets are empty and through the apertures you can just tell that the face concealed beneath the mask is heavily disfigured.

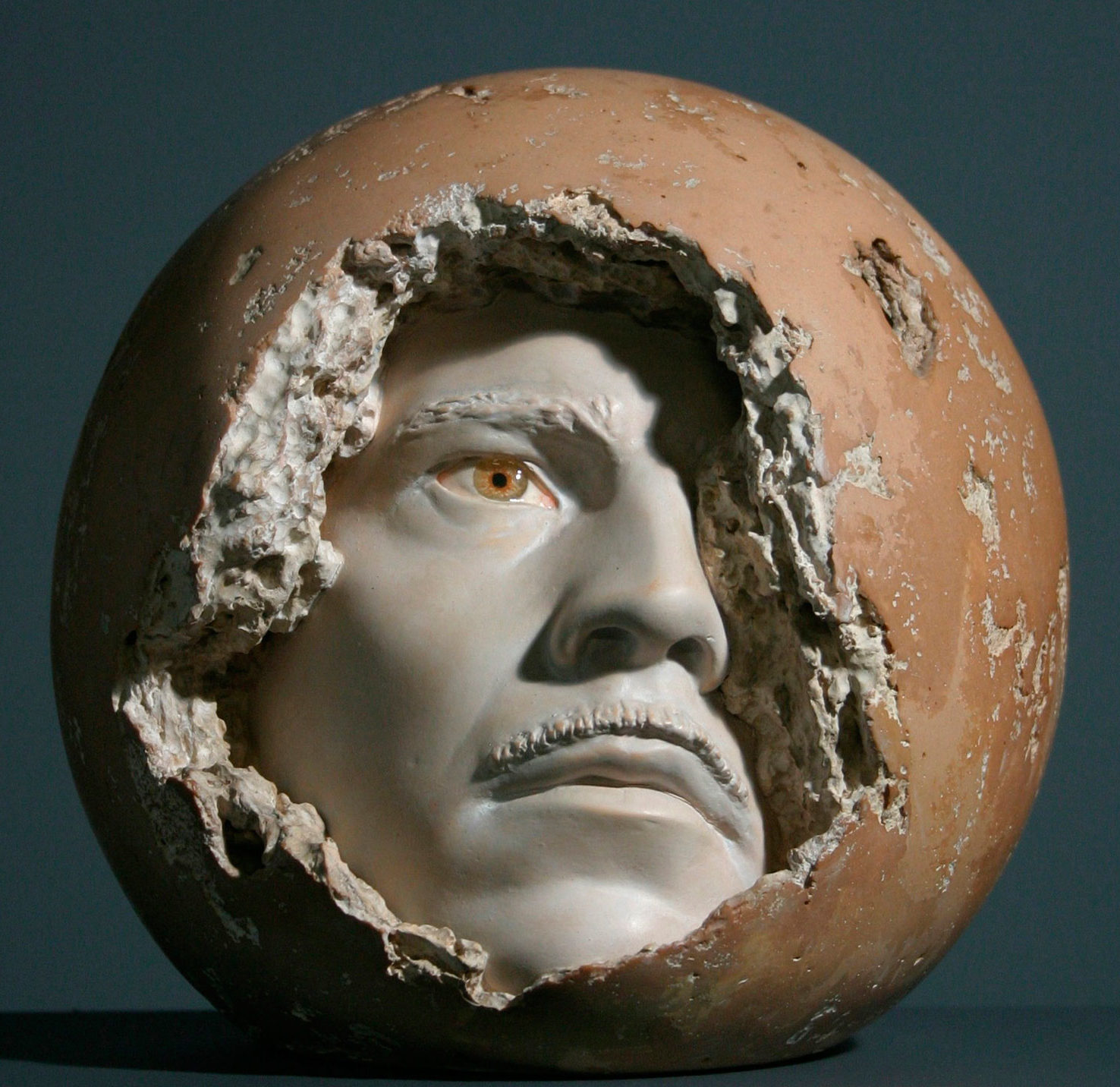

There is often in Kern’s sculpture this sense of layering, of shells covering a damaged inner being, of forms being chipped away by time, revealing inner truths. The busts, such as Globe and Imago, are orbs and boxes split open, as if by an axe blow. From within the fissures of each one, a forlorn human head stares out. One of the staring heads (Self-Portrait) is Kern’s.

The faces of Kern’s figures tend to have the same expression. The mouth is rigidly set. The eyes, when not missing, are open, but closed to the world. These are faces that have seen into the abyss and do not want to see anymore. The faces recur in all of the sculptures that run the length of the hallway that serves as the second exhibition space. From afar these sculptures resemble spotlight floor lamps, the kind you find scattered around a film set. But on closer inspection you can see trapped within each glass bulb a human face, or several faces merging into each other. The mood of these pieces, which have titles like Stop Soon, Heirloom, and Too Late, is of vast, eternal regret. They bring to mind twins fighting for space within the womb, disembodied heads frozen in cryogenic pods, an astronaut separated from his mission, doomed to float forever through outer space.

The third and largest exhibition space is filled with horses. Kern began to sculpt horses when, he told the Times, “one day I decided now I’m going to make a horse.” This tends to be the level of Kern’s introspection, at least in his public statements. As it turned out Kern made many horses, of various sizes, though all are reproduced from the same original model. Miniature figurines march around the perimeter of the room. Though they are also made of polyester resin, the material is here somehow made to resemble, variously, bronze, clay, alabaster, tin, terracotta, jade. (The exhibition does not disclose Kern’s methods, though one display case shows the rusting tools he uses in his studio: cheese graters, slotted spoons, a whittled-down kitchen knife, dental instruments, tailor shears.)

Advertisement

The horses have a lighter spirit than the confined deformed heads, but they retain Kern’s sardonic gruesome humor. The horse in Holy One is perforated by gaping holes. In Remember Papa’s Accident a naked man wearing a carnival mask stands jauntily astride the back of a horse, but one of his arms has been severed near the shoulder joint. A ballerina dances on the bloated belly of a dead horse in Dance on Trigger.

At the center of the room stand four life-size horses, in various states of distress—Kern’s four horses of the apocalypse. These sculptures have a regal, divine bearing and not only because of their size. Only one, Circus I, retains the element of the grotesque that otherwise dominates his work: a slender, disembodied arm strokes the neck of a fallen horse lying on its side, its stomach distended, its limbs amputated. Two of the other life-size horses represent the show’s conflicting moods. A winged goddess, wearing nothing but a birdlike aerodynamic mask, rides, and melts into, a white horse in Silent Myth. It is the exhibition’s one unambiguously triumphant piece. In opposition stands Silent Myth II, a headless woman in a death shawl riding a black horse. She is a messenger of death, or Death herself. The dull blackness of the form, the power of the horse’s legs, the void where the head should be, give the monolith an implacable spookiness. The sculpture is at once heavy and empty—a black hole.

The credit panels on the wall persistently remind the visitor that the dozens of sculptures on display are, with only a handful of exceptions, on loan from the artist. Kern has lived amidst this charming cabinet of horrors for decades; one can only imagine what it must be like to walk through his studio at night. What he must feel upon seeing his mythic visions, his inner demons, exposed for the world—or at least New Orleans—to see, we can only guess.

“I can never get into somebody else’s brain,” he told the Times. “We are all isolated in that sense in our own worlds.” I don’t think he is entirely correct about that. Once his work entered my brain I could not get it out. We call a work “haunting” not when it’s frightening or creepy but when it exposes something within us that we would prefer to remain hidden. I found Kern’s figures startling not because I had never seen anything like them before—but the opposite. The sense of recognition was immediate and visceral. I was certain I had seen these images before, in some other time, somewhere very far away from here.

“Arthur Kern: The Surreal Life of a Reclusive Sculptor” is on view at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art through July 17.