Although America long ago had a Virginia architect as president—Thomas Jefferson—never until this year had someone reached its highest office from the considerably less elevated realms of New York real-estate development, Atlantic City casinos, and TV reality shows. Grotesque though the rise of Donald Trump has seemed to many, his political ascendance has struck those of us who love architecture as a particularly personal affront, given our familiarity with his forty-year record as the foremost architectural schlockmeister and urban design vulgarian of his generation. Trump’s insistence, wholly at odds with the built and economic evidence, that he saved the faltering New York City of the 1970s through his characteristically glitzy but inevitably cheesy projects was but one in a series of big lies that culminated in his pronouncement, at the Republican National Convention this past summer, that he alone could solve America’s problems.

Nonetheless, Trump’s brand of alternative reality clearly has a strong popular appeal, based as it is on wild claims and raw emotion, and it oddly reminded me of one of my earliest critical assignments. Forty years ago, Architectural Record asked me to review the granddaddy of all “what if?” books on the building art, Alison Sky and Michelle Stone’s Unbuilt America: Forgotten Architecture in the United States from Thomas Jefferson to the Space Age (1976), which I hailed as “one of the most thought-provoking architecture books in recent years.”

Unbuilt America appeared just as orthodox modernism was giving way to postmodernism, and it perfectly complemented the more expansive view of architectural history then emerging (which also paralleled the growing inclusiveness in our society at large from the 1960s onward). The book’s rare appeal to a general readership owed much to a widespread fascination with “what might have been,” and it inspired a host of similar volumes, including the recently published Never Built New York by Greg Goldin and Sam Lubell, co-authors of Never Built Los Angeles (which accompanied an eponymous exhibition held at LA’s Architecture and Design Museum in 2013.)

Though Never Built New York contains some well-known proposals that never made it past the design stage—among them Frank Lloyd Wright’s St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie Residence Towers (1927) and R. Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao’s Dome Over Manhattan (1960)—much else will be revelatory even to specialists. For example, I’d never known about Cass Gilbert’s 1931 attempt to conceal the steel latticework towers of Othmar Ammann’s George Washington Bridge beneath a stripped classical slipcover of pink granite. Likewise I’d been unaware of Philip Johnson’s monster quartet of Brutalist apartment slabs for Chelsea (1967), not far from where the High Line has lately become a magnet for high-style condo architecture.

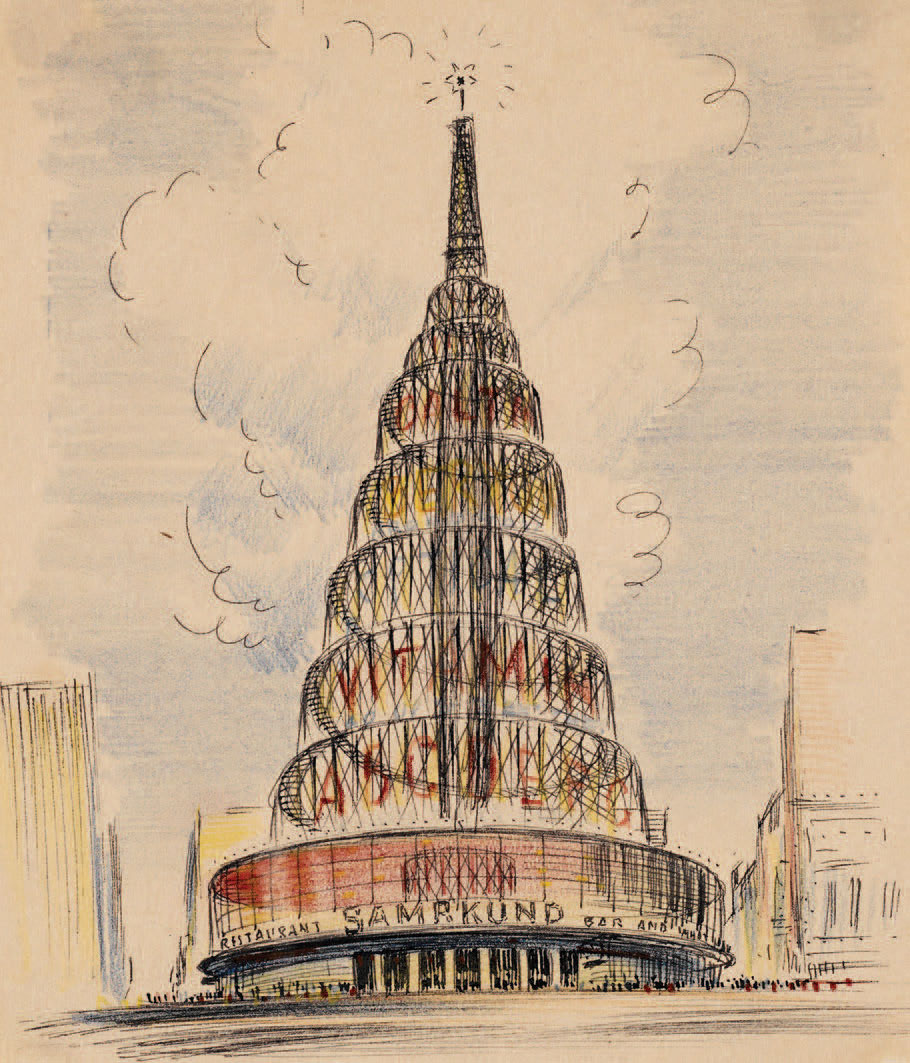

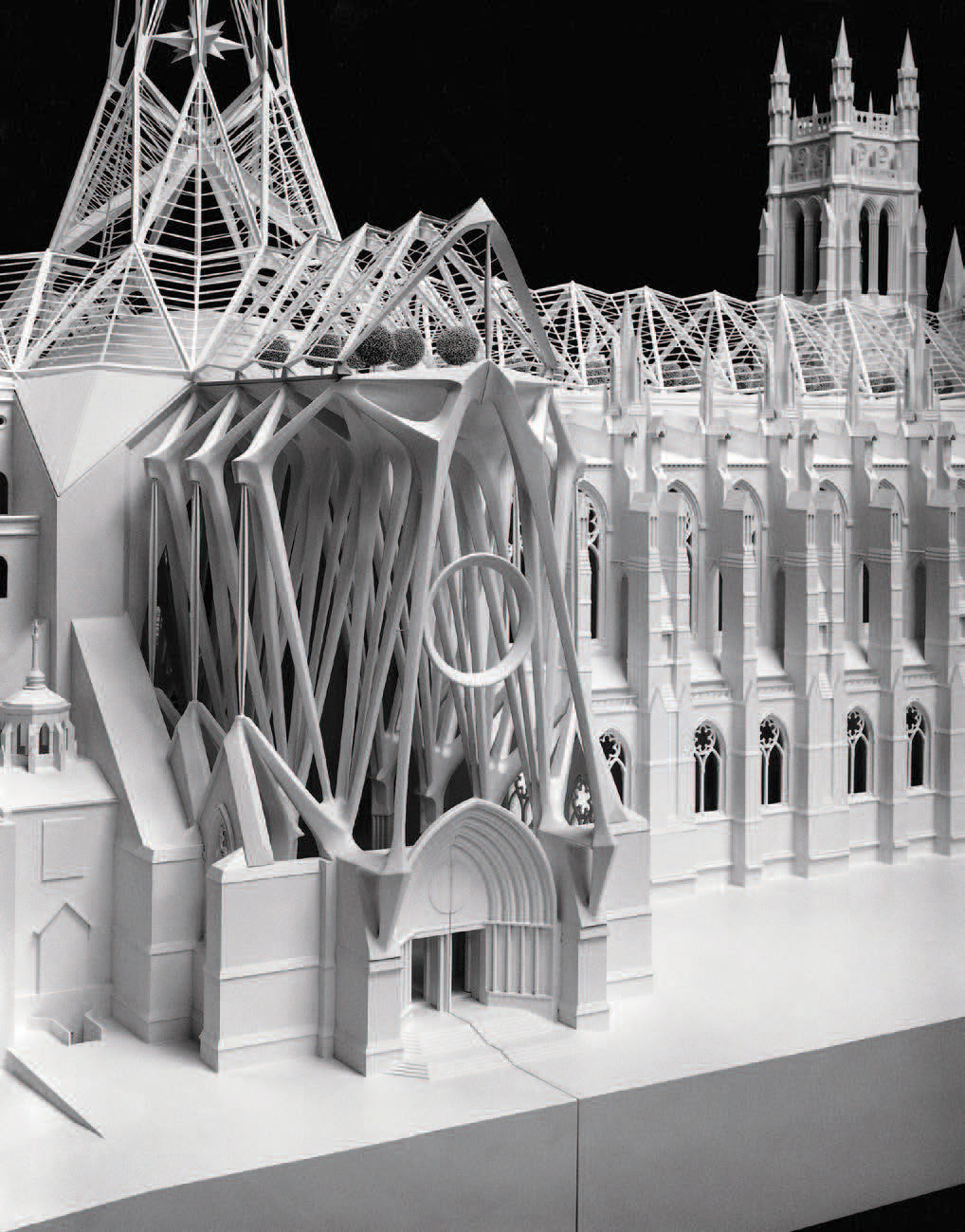

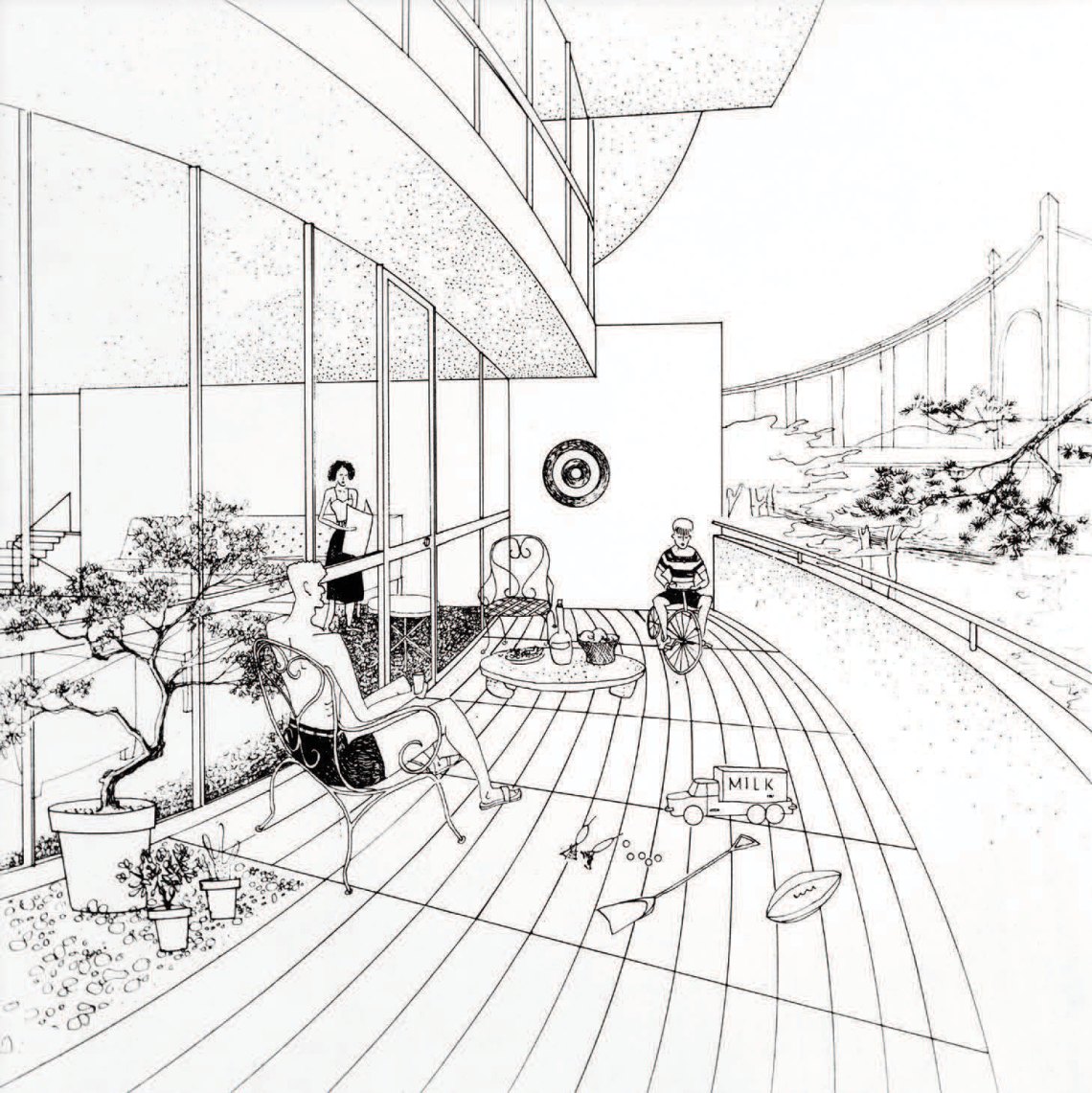

Echoing Unbuilt America’s original mix, the new survey encompasses ideas that were fortunately rejected (Santiago Calatrava’s eerily skeletal 1992 proposal for completing the Cathedral of St. John the Divine) and regrettably thwarted (Joseph Urban’s boffo 1927 Broadway theater for the experimental impresario Max Reinhardt, which would have been as much of a spectacle as anything on its stage). Many were thoroughly impractical (John A. Harris’s demented 1924 call for draining the East River to create more land, and Norman Sher’s equally crazy 1934 plan to dam the Hudson River and join Manhattan’s West Side with New Jersey), while others were ingeniously inventive (I.M. Pei’s Helix of 1957, a cylindrical tower with pie-shaped apartments that could be expanded or contracted as residents’ need for space changed.)

Architectural competitions provide a mother-lode of material for such roundups, and Never Built New York also includes hilarious duds such as an entry in the 1858 contest to design Central Park submitted by one John Rink resembling a green Suzani embroidery from Central Asia. Considering this dreadful alternative, it is not surprising that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s sinuously flowing and veritably breathing proposal jumped out at the jurors and won their approval.

Tellingly, the outsized scale of Manhattan’s manmade environment—its legendary skyscrapers, unrelenting right-angled street plan, and dramatic landscape centerpiece—dwarfs even the most grandiose visions for single buildings. Thus, the individual structures in Never Built New York tend to be overshadowed by the vast infrastructure needed to service a tightly contained metropolis of millions.

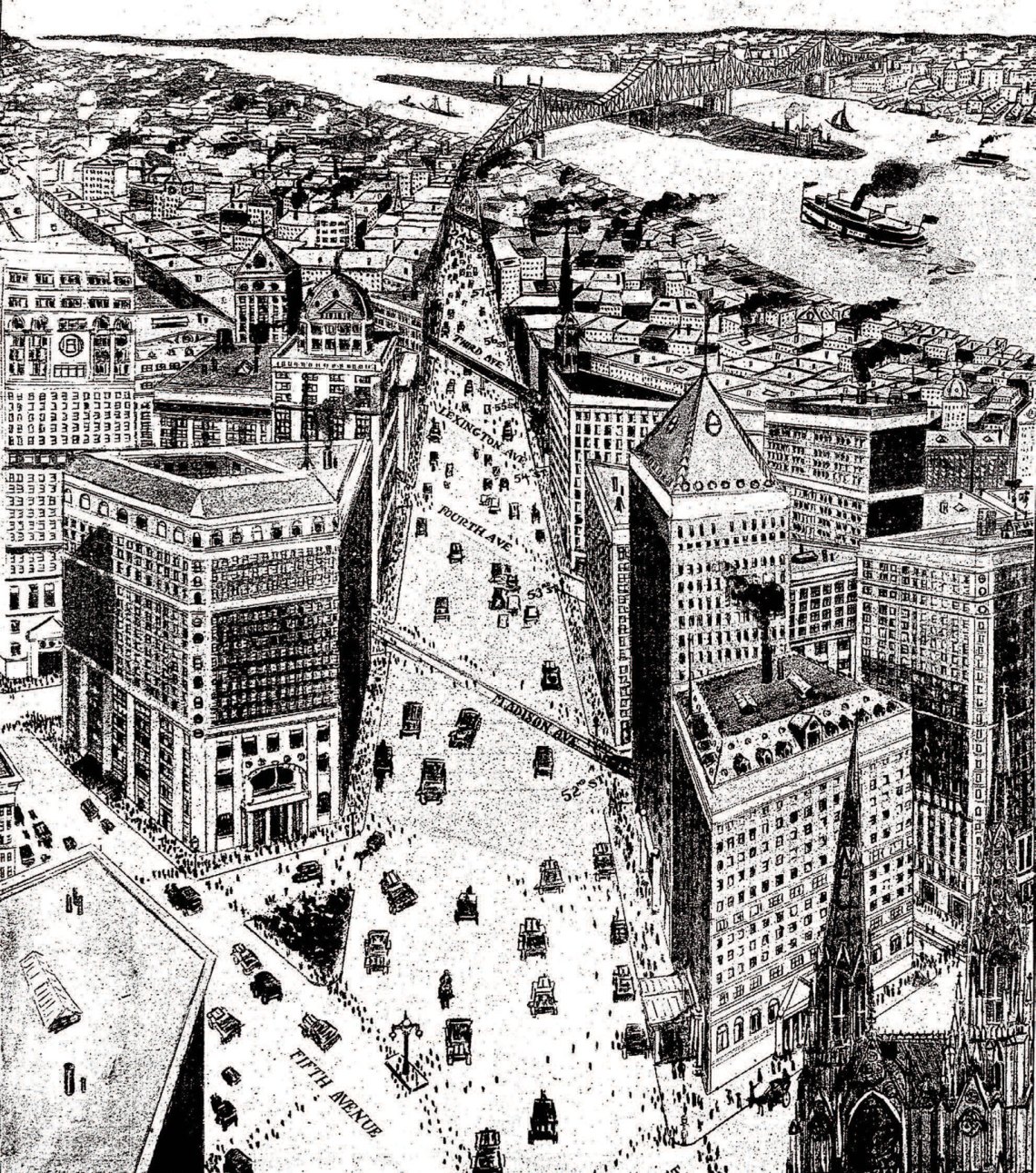

Several projects in the book address the extreme transportation congestion that already plagued Manhattan by the mid-nineteenth century and prompted solutions like Egbert Ludovicus Viele’s Arcade Under-Ground Railway of 1866, a fictive forerunner of the subway system. This pipedream eschewed deep digging, since steam trains would need to run above ground, while vehicular and pedestrian traffic were to be hoisted up to an elevated roadway fifteen feet above existing sidewalks. (The initiative was killed by a gubernatorial veto after objections from ground-floor merchants along the right-of-way.) And then there are the manias to improve street traffic that have sporadically gripped urban planners, especially Beaux-Arts-era campaigns for diagonal, grid-slicing thoroughfares in imitation of Baron Haussmann’s radial Parisian boulevards.

Advertisement

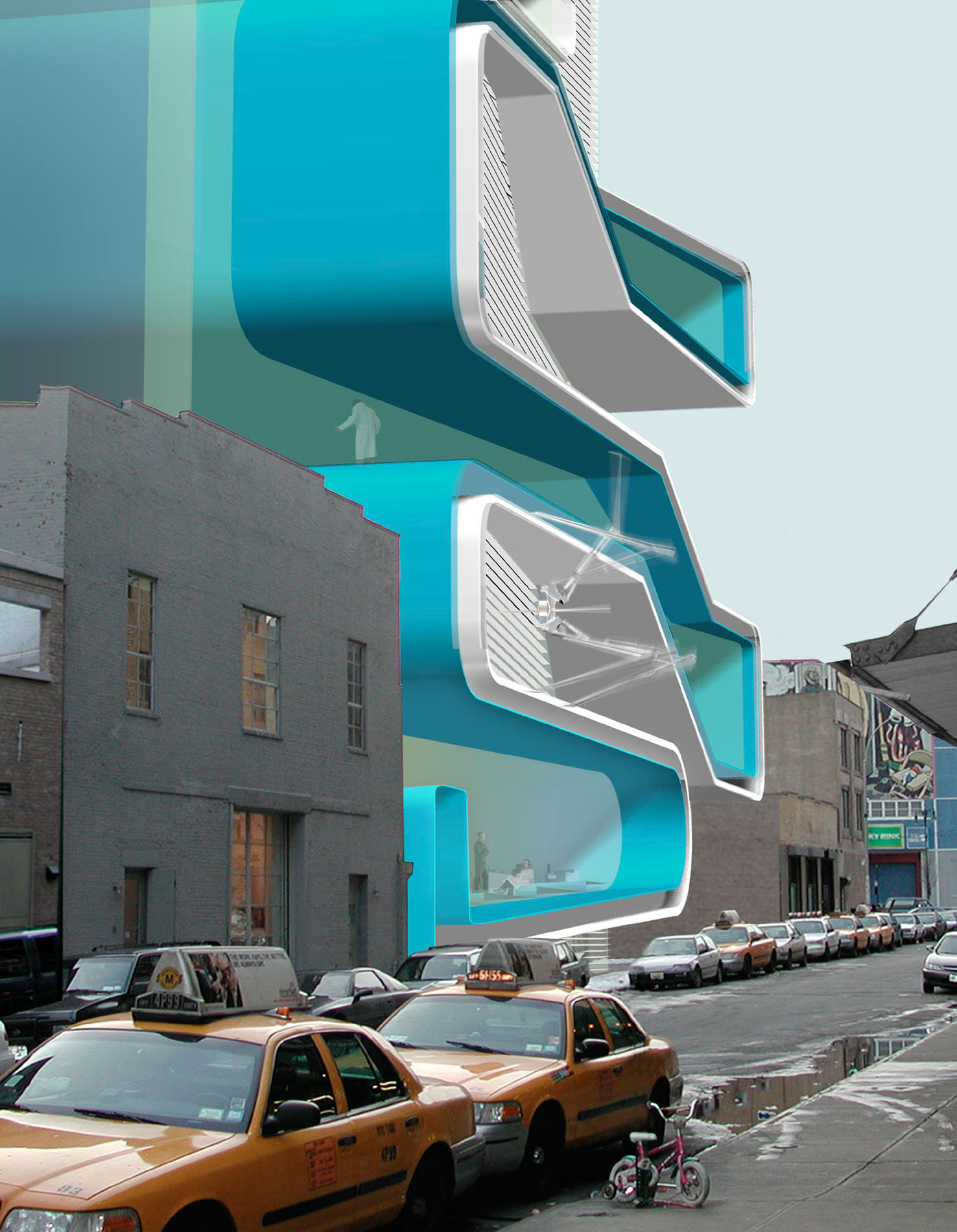

What sets Never Built New York apart from its predecessors are the numerous schemes depicted through computer-generated imagery, which can now attain such verisimilitude that it’s hard to tell if you’re looking at a completed project or a mere predictive apparition. This blurring of reality can be of immense commercial benefit (no need to tell that to Trump), and it is widely assumed that the more lifelike an illustration, the more a client will believe that what it shows can be realized.

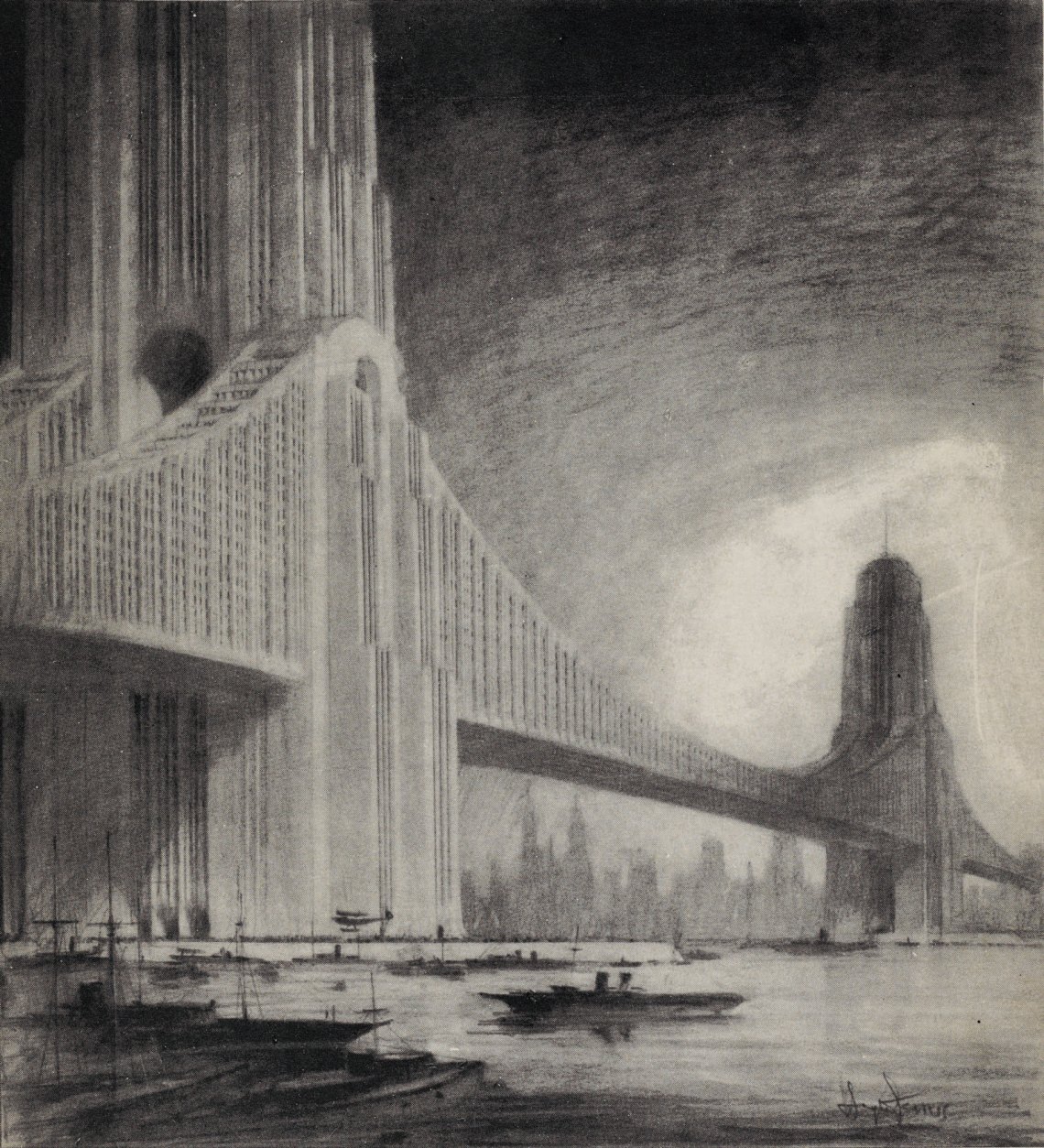

However, Never Built New York repeatedly demonstrates that the psychological charge conveyed by a powerful drawing outstrips even the most realistic digital simulacrum. The celebrated architectural draftsman Hugh Ferriss, who flourished in the Twenties and Thirties, is represented by his charcoal sketches of boldly imaginative cityscapes, which seem plausible because of their appeal to the period’s deep belief in progress as the basis for modern civilization.

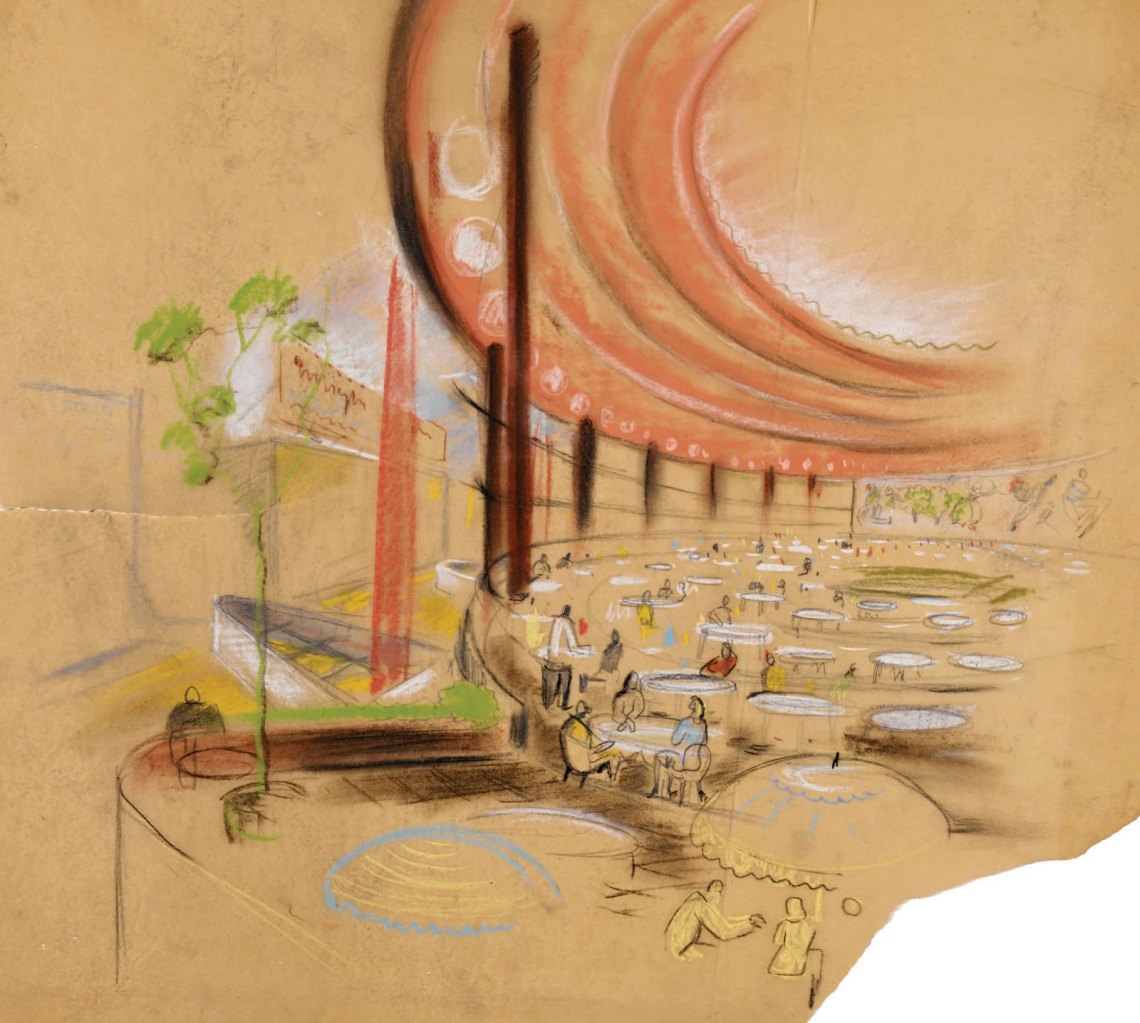

Similarly, its hard to resist the arrestingly colored renderings of Ely Jacques Kahn, the hugely successful New York-born Beaux-Arts-trained architect whose lively Art Deco commercial buildings continue to adorn the city. Kahn’s drawings, on yellow tracing paper, of his proposed Dowling Theater of 1945 on Times Square convey the same mood of postwar confidence and nocturnal glamour evoked in Martin Scorsese’s cinematic love letter to that time and place, New York, New York (1977). If the character of every great cosmopolis depends to a large extent on conspiratorial belief in a shared myth, then these compelling dream images of a bygone Gotham still work their magic today.

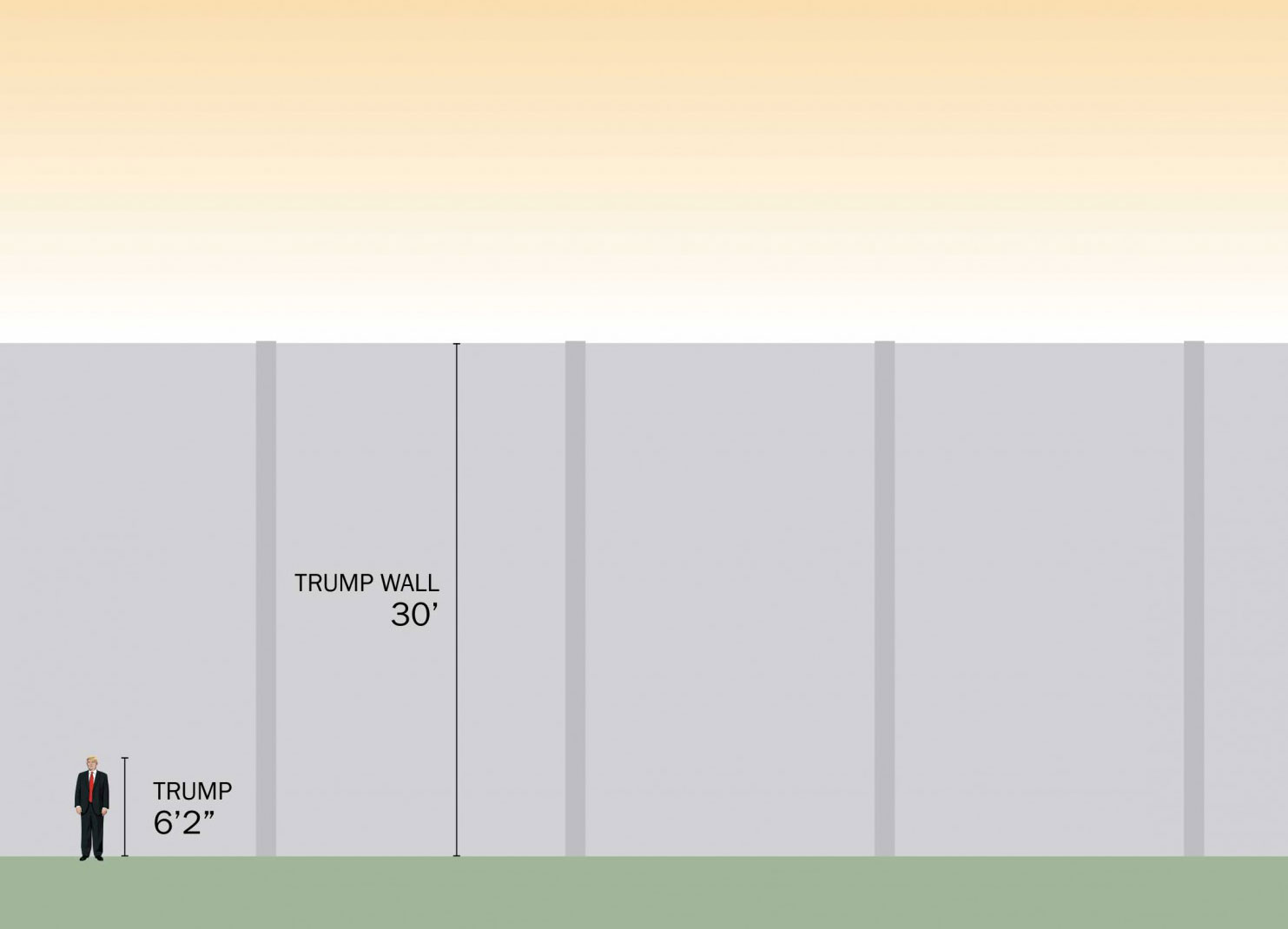

One of course cannot help but wonder what Trump will impose architecturally on our national landscape, especially since he has promised to create vast infrastructure projects, most notoriously his “big, beautiful, powerful wall” along the 1,989-mile expanse of our border with Mexico. Though he has vowed to make Mexico pay for that barrier, he is far more vague about how his other mega-construction schemes would be financed.

Trump has announced that he will put his business operations into a “blind trust” controlled by his three oldest children, but how truly disinterested can a famously controlling parent and his financially enmeshed offspring be under such circumstances? This cozy familial set-up raises the specter of wholesale conflict-of-interest—“Nobody builds walls better than me, believe me,” he has assured us—to say nothing of outright corruption if he oversees such a massive undertaking.

Time and again I have written that one of the surest reflections of a society’s values can be found in what it builds. Despite uncertainties about exactly what travails the Trump presidency will bring us, I am convinced that the architectural imprint he has already imposed—extrapolated to a national scale—tells us all we need to know.

Never Built New York is published by Metropolis Books and distributed by Artbook DAP.