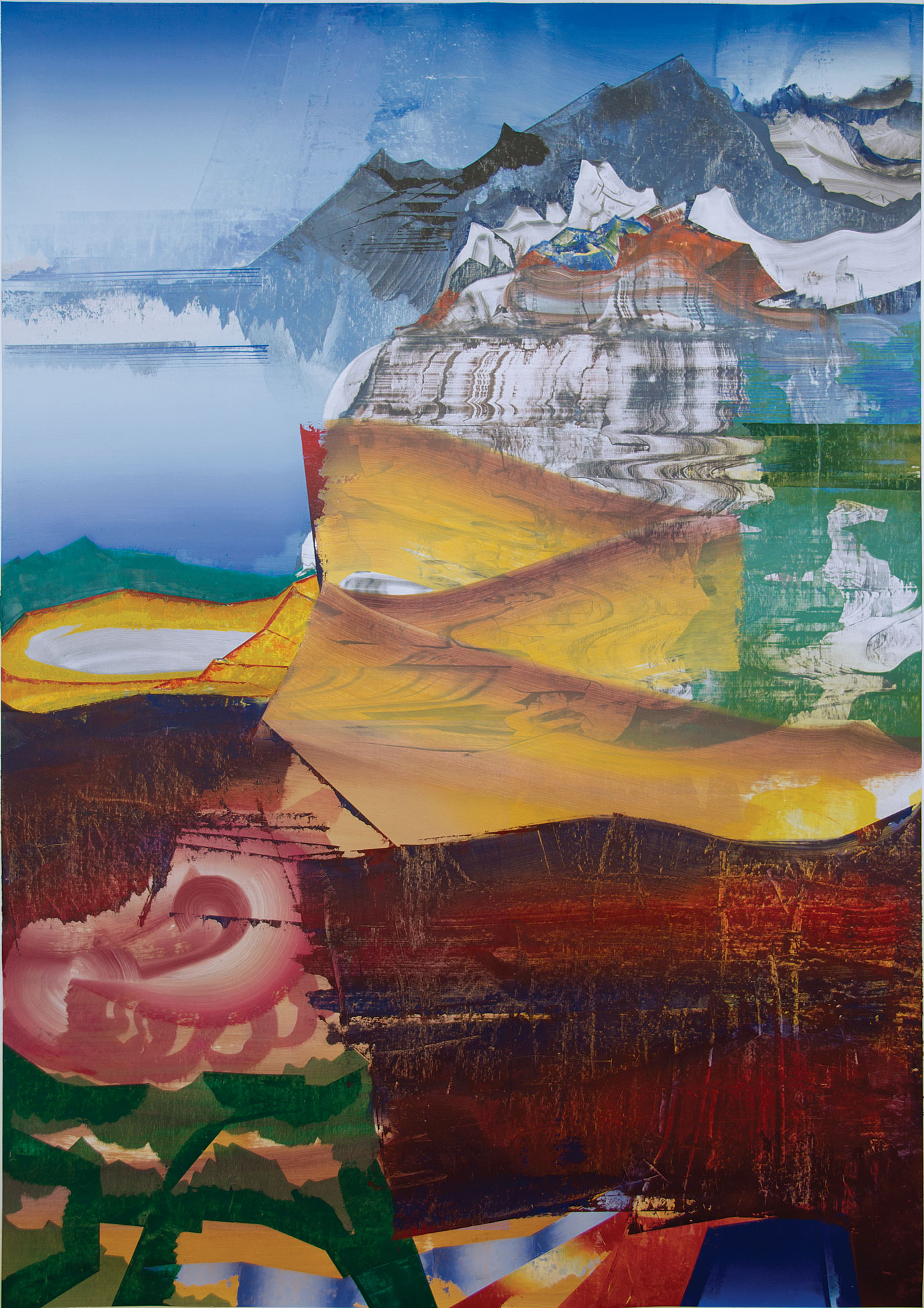

Elliott Green’s paintings appear to be in continuous motion, the way animals, plants, and ultimately rocks and mountains are in continuous motion, even when our human vision fails to apprehend it. Placing great thick gestures of paint amid minute intricacies and vice versa, his compositions demonstrate the movement of the universe on both the macro and the micro scales. They might seem analogous to the huge, all-but-abstract photographs of Andreas Gursky or Edward Burtynsky (whose high-resolution digital work similarly presents the eye with sights it can’t otherwise see), but Green’s paintings are first and last human documents, their rhythms legible to the pulse and not above trying to accelerate it.

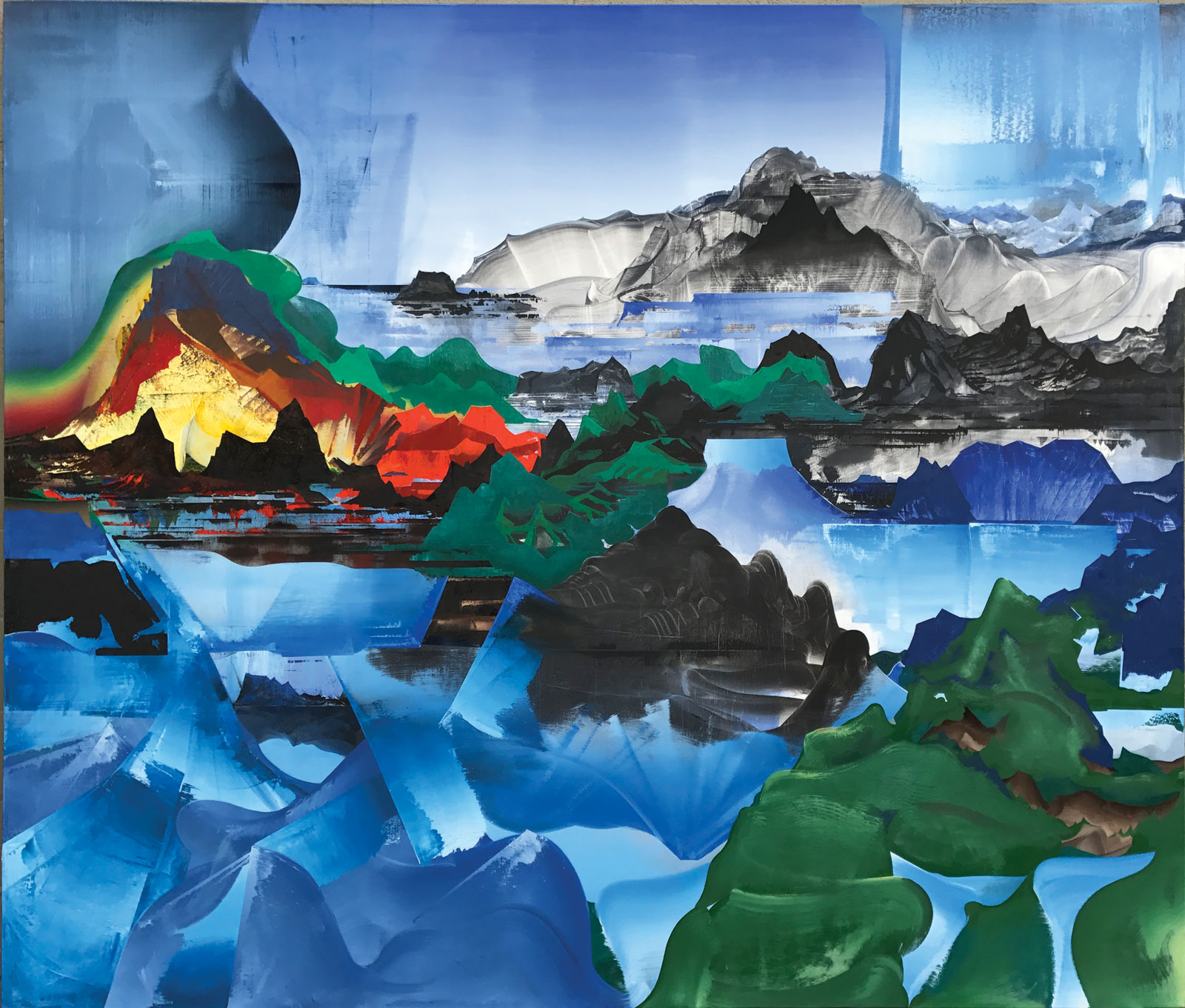

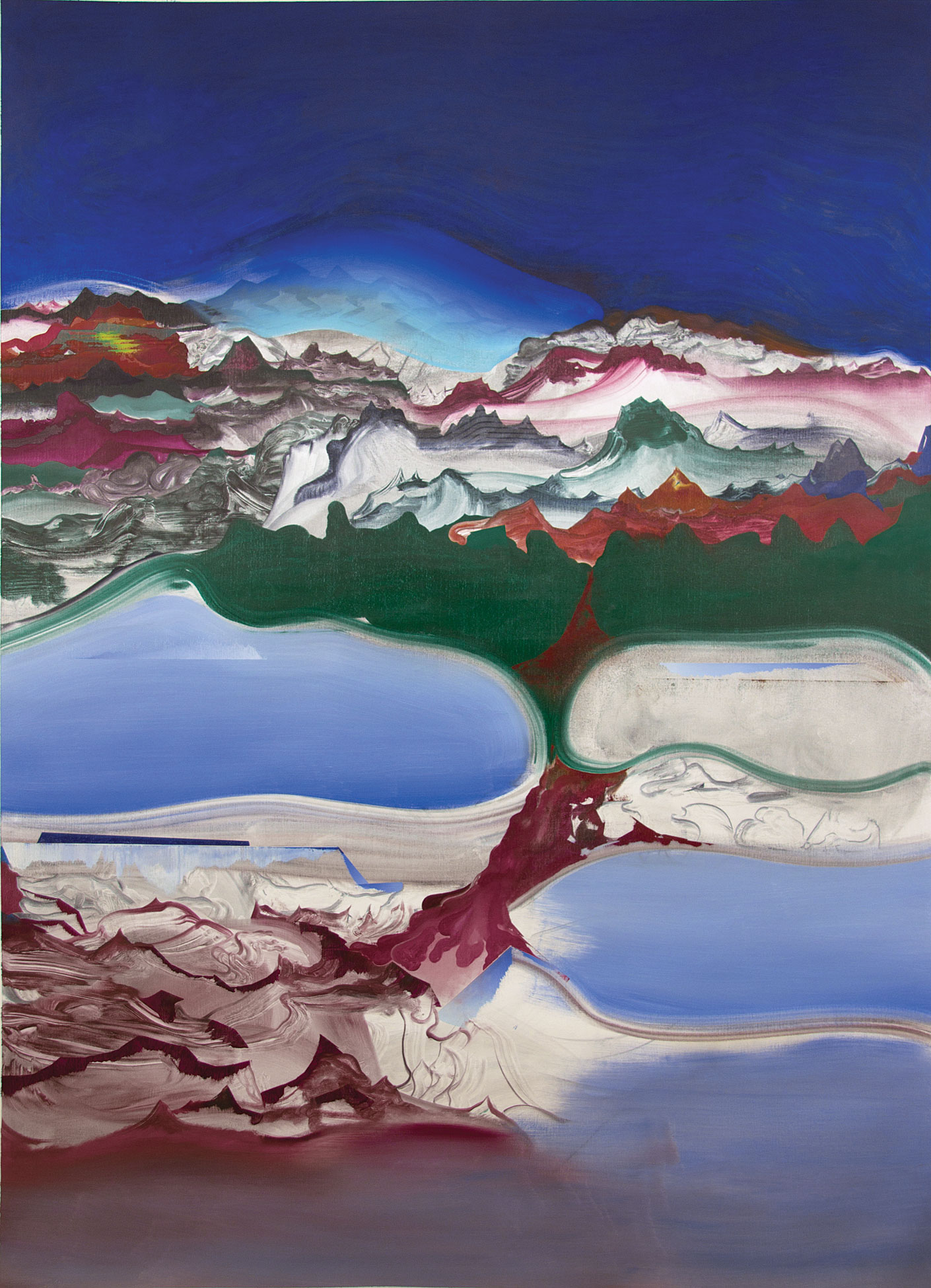

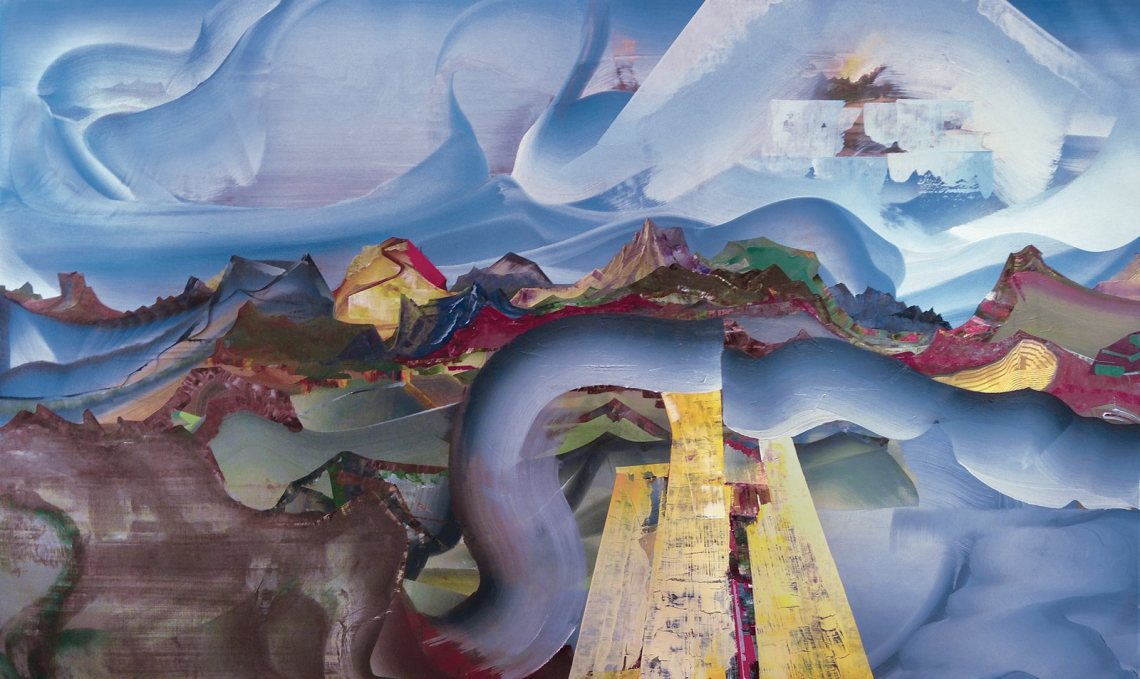

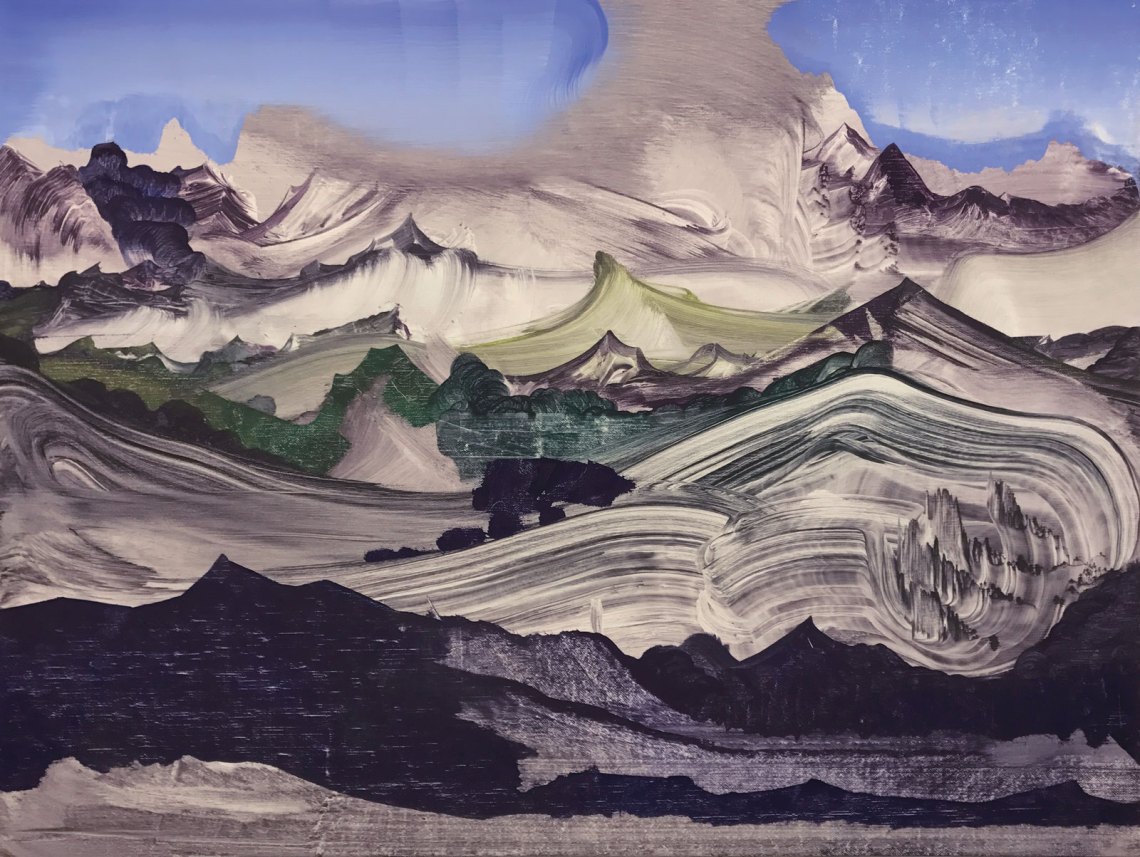

That being so, the paintings on view through March 26 at the Pierogi Gallery in New York City can’t help invoking intellectual movement as well: they set the viewer’s mind tumbling toward successive interpretations. The idioms of landscape painting have been set loose on Green’s canvases, and we’re invited to see top-shelf vistas everywhere—with all that we expect of them: peaks, shores, skies, and the great luxury of distance itself, which signifies time. But when a swath of blue-to-silver or green-to-gray makes contact with another swatch of color, the suggestion of mountain or lake is revoked and we’re made to see the flatness of the canvas again, the pigment as pigment alone.

Green has said that he works by accretion, layering each canvas with shapes and colors, the result being that substantial histories of composition are hidden under each completed work. Improvisation is central to this method. His lines travel with such elegance that each one exudes an almost physical coolness—you feel Green’s assurance with line and volume leaning on the flux of improvisation—and this tension between restraint and randomness forms something like a habitable climate in almost every painting (in a few the climate feels deliberately hostile to life).

Layering seems the subject of Green’s Fist and Shadow (2014), where most of the canvas is textured with a translucent wash of grayish brown. Sharp, bright shapes are swimming half-visibly beneath it—a rare sight, since Green usually covers earlier actions with opacity. You can hardly help reading the oval on the right as the eponymous fist—its plump contours maybe referencing Green’s earlier work, which was often composed around cartoonish humanoids gestured in exquisitely playful lines.

At once the potential for movement is awoken: Will there be impact between this fist and shadow, and what happens to a shadow when it’s punched? Rather than being knocked out, it seems likely to disperse and banish light from the land. As is often the case in Green’s work, the darkest questions flow from a comic style. Note the shapes that ask to be read as puffs of chimney smoke near the top of Bone Dust Beach (2013): they look storybook-harmless, and then they billow into something like a deadly pale zygote tethered in the sky. But perpetrating such acts of narrative on Green’s canvases must fill the viewer with ambivalence: you’re teased into seeing things that aren’t really present. It’s almost as if this systole-diastole between interpretation and unprejudiced seeing were the aim of each painting.

The aptly titled Polyvalence (2013) is a procession of summits, rocky and/or aqueous, each “ridge” filled with layers of color older than its contours. And these aren’t the Berkshires: they’re sublime horizons, a Hokusai idea of what it is to be at one with nature. Yet a crucial polyvalence here and in Green’s other canvases is that many of these lines or ruptures look distinctly inorganic. The wide pipes of color that often snake through his paintings remind me of ducts in the dystopian masterpiece Brazil. Green’s shapes look nothing like ducts and aren’t intended to look like ducts. But in the context of his abstract compositions they look nearly representational. And then one of them—in the kind of instant, unlabored allusion that’s at home in his work—forms a near half-circle near the middle of The Photon Skirt (2015), echoing the concentric rings of the known universe in Giovanni di Paolo’s compact Quattrocento epic The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise.

Green’s work is often brought into focus by his titles; the images coalesce like iron filings under the magnetic pull of their names. It may be, for example, that the poppy red near the corner of Shark Mouth is neither hostile nor benign, just a morally neutral concentration of carmine; but the title invests the painting’s tight rhythm of curves and angles with the jaunty malignity of a killer that can afford to toy with its prey. We tend to think of the natural world as an ascetic, not just indifferent to us but favoring utility over loveliness and efficiency over pleasure. Yet the splendor of Green’s paintings reminds us that nature can be baroque, its organisms organized to the point of rococo. The threadbare opposition of nature and art—often miscast in aesthetic terms as authenticity versus theatricality—is beautifully scrambled on Green’s canvases. And to appreciate nature’s formality of purpose is to arrive at a fresh vision of our fundamentally human hunger for form.

Advertisement

Hunger is important to mention because we so often imagine formal questions to be antiseptic or apolitical, living as we do in a time when consumers are eager for memoir, personal confession, the who not the how of a thing. Yet a painting like Green’s Expander (2016)—which seems to me a bold series of formal departures, suggesting the unceasing incursions of time’s fourth dimension into what we know as the first three and thereby hinting at an identity’s struggle for coherence, while refusing such readings in just the way that, say, Emily Dickinson’s “My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun -” resists paraphrase—a painting like Expander operates like an expander on the mind, inserting thoughts (see my foregoing em dashes) while earlier thoughts are still forming.

Adapted from Jana Prikryl’s essay in the catalog for Elliott Green’s “Human Nature,” which is on view at the Pierogi Gallery through March 26.