Is a translator effectively the co-author of a text and if so should he or she be paid a royalty as authors are?

After presenting a book of mine, or rather, its German translation, in Berlin, I found myself in a bar discussing this question with two experienced translators, Ulrike Becker and Ruth Keen. Rather than the nature of a translator’s co-authorship itself, our discussion was kicked off by the fact that very few translators actually receive major benefits from royalties—even in Germany, where publishers are obliged to grant them. Over a long career, Ruth just once received a handsome €10,000-plus when a book about Napoleon’s march on Moscow unexpectedly took off. Ulrike once received a couple of thousand when a literary novel made it onto the bestseller list. Otherwise, it’s peanuts.

Why is this?

As in most countries, German literary translators are paid for their work on the basis of its length; something that, in this case, is calculated at a rate of around $20-25 a page. Not a lot. In the US or England, far fewer literary works are translated and rates vary a great deal. But if a royalty is granted at all (and I for one was never given a royalty in the US), the initial payment based on length is usually considered an advance against it. Hence, if a translator has been paid, say, $8,000 for a book and granted a royalty of 1 percent on a cover price of $20, the book would need to sell 40,000 copies before the royalty brought in any additional money. And 40,000 copies is an unusually big sale.

However, as Ruth explains to me, German law has been generous to translators and a recent court ruling ordered that the initial payment must not be offset against royalties. What the ruling didn’t do, however, was prevent the publishers from establishing a threshold below which royalties would not be paid, usually set at 5,000 or 8,000 copies, while the royalty will be as low as 0.8 percent, or even 0.6 percent. Since in Germany few books sell more than 5,000 copies, the result is that few translators see any money from these arrangements.

All the same, the occasional jackpot is surely better than none at all. So you would think. Ulrike tells me the story of Karin Krieger, who became a translator’s hero when, in 1999, she took the publisher Piper to court over a royalty question. Krieger had translated three novels by the Italian writer Alessandro Baricco. When these began to sell well she tried to get the publishers to honor a rather vague contractual clause granting her “a fair share of the profits” (royalties were not mandatory at that time). The publisher responded, unexpectedly and quite unusually, by having the books retranslated by another translator with a contract more favorable to the publisher.

After five years’ litigation, Krieger eventually won her case and the money she was owed, but the sequence of events suggests the essential difference between translators and authors: Piper could never have tried to deprive Baricco of his royalties, since without him there would have been no books and no sales. He was not replaceable. But however fine Krieger’s translations, the publisher felt that the same commercial result could be achieved with another translator. It’s not that translation work is ever easy; on the contrary. Simply that it rarely requires a unique talent. Krieger wasn’t essential. She could be replaced.

At this point it’s worth remembering why royalties were introduced in the first place. Before the eighteenth century writers would sell a work to a printer for a lump sum and the printer would make little or much depending on how many copies they managed to sell. Writers, seeing printers grow rich (or some printers), wanted a share of the wealth they felt that they more than anyone else had created; hence in the early eighteenth century the first move, in Britain, to concede that writers owned what later came to be called “intellectual property”—their writing—and hence had a right to a percentage of the income for every copy sold.

It could be argued that while this was “fair” as an arrangement between printers and authors, it hardly meant that a writer’s income would reflect the quality of their writing and the work put into it—would, that is, be fair in some absolute sense. Today a blockbuster that sells globally—Dan Brown, Stephenie Meyer—will make its author many millions, while a fine work of poetry might bring in just a few hundred dollars. If anything, one could say that royalties were an invitation to writers to aim their work at the largest possible audience able to afford a mass-market paperback.

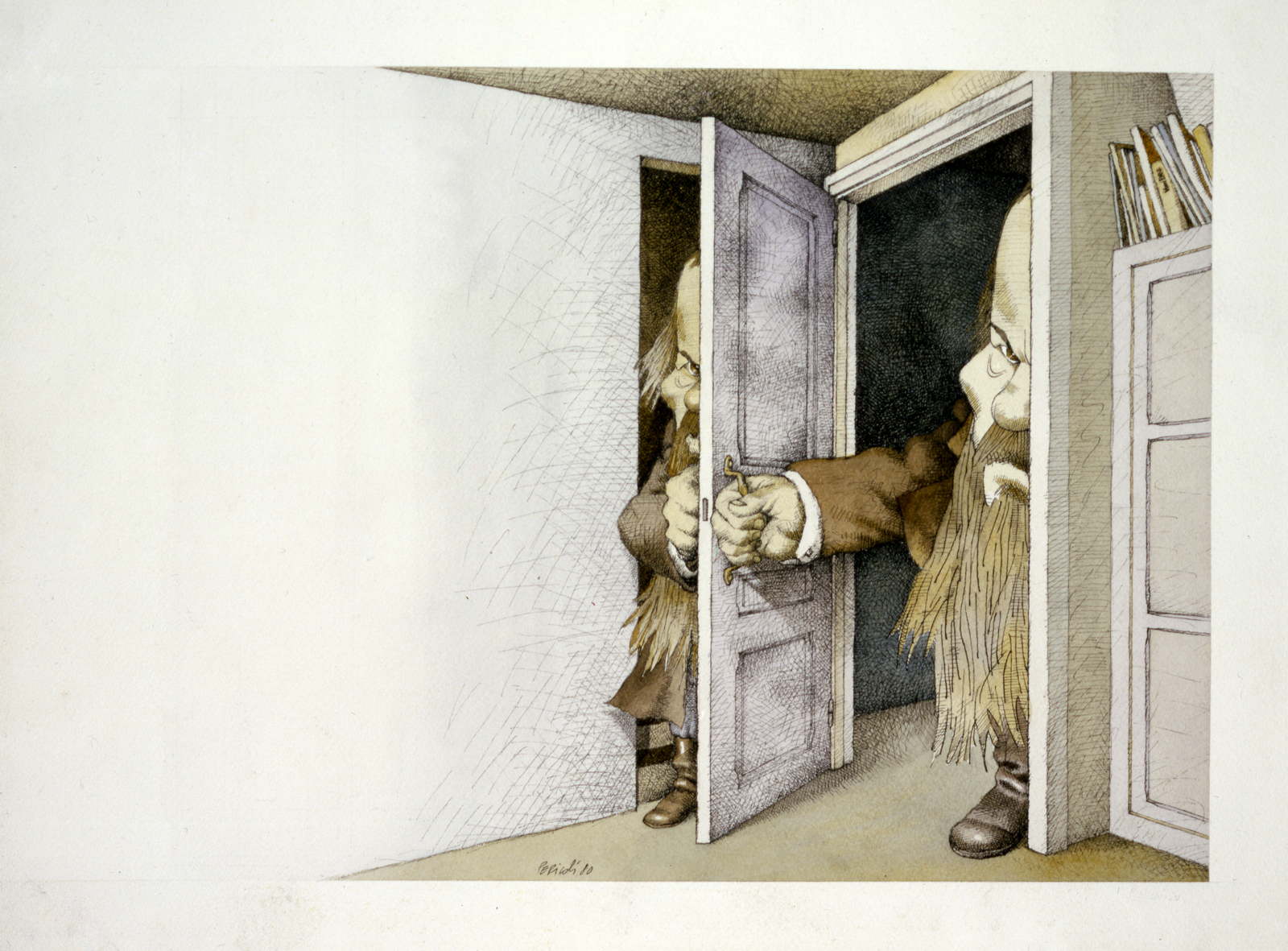

That said, whatever is in that paperback really is the author’s creation. He or she will have had to sit down and write a substantial piece of work, not knowing how it will come out, not knowing for sure whether a publisher will buy it or whether, having bought it, they will be able to sell it. In short, the author has to fill an empty space, to create something where there was nothing. The translator, on the other hand, is in most cases commissioned to do a job. It could be the blockbuster, it could be the poetry. Sentence by sentence, the work is already there. However difficult it may be bringing it into another language, translators do not have to start from scratch, and they rarely have much choice, at least at the beginning of their careers, as to what kind of work they are translating. Certainly, in my own experience, nothing could be more different than settling down to a day’s writing as opposed to a day’s translating.

Advertisement

Two ideas drive the now decades-old campaign to extend royalty payments to translators. The first is practical: since publishers have tended to resist paying rates that would constitute a decent income for translators, one that corresponds to the professional skill and long hours involved, introducing a royalty clause into the contract ensures that at least in cases where a translated book makes serious money the translator will get some share of it. The second is conceptual: every translation is different, every translation requires a degree of creativity, hence the translation is “intellectual property” and as such should be considered authorship and receive the same treatment authors receive.

The problem with the first of these ideas is that, in so far as a translator’s income is royalty-based, it will depend entirely on how publishers distribute the translations they commission. If, for example, we imagine two German translators with the same qualities and one is commissioned to translate Fifty Shades Part V and the other a book of short stories by a first-time New Zealand writer, one will make a fortune and the other very likely a pittance. Of course, the same is true, as we said, for the authors. If both receive 10 percent per copy, E.L. James will grow fabulously rich and the New Zealand short-story writer, however brilliant, would be well advised not to leave his regular job. Yet royalties are not a divisive issue among writers for the simple reason that whatever one thinks of the qualities of a work like Fifty Shades, no one disputes that E.L. James was the person who had the idea for the book and took the risk of writing it. It is her work, it reflects her mind. Let her have her 10 percent.

The same is not true for the translator, for whom translating Fifty Shades with a royalty is simply a huge windfall for a task that may even be easier than translating far less remunerative books. What’s more, one can safely disclaim all responsibility for the embarrassing content! At this point the institution of royalties threatens to divide translators. An Italian translator told me how all Dan Brown’s translators had been brought together in Europe to receive the novel Inferno and be briefed on various translation issues. The French translator was in an excellent mood since France, like Germany, now compels publishers to grant royalties. Others were bound to reflect that they would be receiving only a few thousand dollars for the whole six hundred pages, no matter how well their translation of the book sold.

The second, conceptual argument is more interesting, but no less problematic. That translation requires creativity is indisputable. As a translator myself, I have no desire to undermine the dignity of the craft. But is this creativity of a kind that constitutes “authorship”? Here are four versions of the opening lines of Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground:

I am a sick man…. I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased. However, I know nothing at all about my disease, and do not know for certain what ails me. I don’t consult a doctor for it, and never have, though I have a respect for medicine and doctors. Besides, I am extremely superstitious, sufficiently so to respect medicine, anyway (I am well-educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious). No, I refuse to consult a doctor from spite. That you probably will not understand. Well, I understand it, though.

—Constance Garnett, 1918

I am a sick man…. I am an angry man. I am an unattractive man. I think there is something wrong with my liver. But I don’t understand the least thing about my illness, and I don’t know for certain what part of me is affected. I am not having any treatment for it, and never have had, although I have a great respect for medicine and for doctors. I am besides extremely superstitious, if only in having such respect for medicine. (I am well educated enough not to be superstitious, but superstitious I am.) No, I refuse treatment out of spite. That is something you will probably not understand. Well, I understand it.

—Jessie Coulson, 1972

I am a sick man…I’m a spiteful man. I’m an unattractive man. I think there is something wrong with my liver. But I cannot make head or tail of my illness and I’m not absolutely certain which part of me is sick. I’m not receiving any treatment, nor have I ever done, although I do respect medicine and doctors. Besides, I’m still extremely superstitious, if only in that I respect medicine. (I’m sufficiently well educated not to be superstitious, but I am.) No, it’s out of spite that I don’t want to be cured. You’ll probably not see fit to understand this. But I do understand it.

—Jane Kentish, 1991

I am a sick man…I am a wicked man. An unattractive man. I think my liver hurts. However, I don’t know a fig about my sickness, and am not sure what it is that hurts me. I am not being treated and never have been, though I respect medicine and doctors. What’s more, I am also superstitious in the extreme; well, at least enough to respect medicine. (I’m sufficiently educated not to be superstitious, but I am.) No, sir, I refuse to be treated out of wickedness. Now, you will certainly not be so good as to understand this. Well, sir, but I understand it.

—Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky 1993

One can make all kinds of distinctions between these translations. “Spiteful,” “angry,” and “wicked,” in the opening line, suggest three rather different qualities; which is right, or at least closer to the original? Why do three of the translations cite this same quality—“spite,” “wickedness”—later as the reason why the narrator has not sought a treatment for his illness, while one, the translation that uses “anger,” does not? We can only assume that the original uses the same word twice but one translator has chosen not to respect that repetition. Two of the translations have a generic “know nothing at all” or “the least thing” about the narrator’s illness, while one has “cannot make head or tail,” introducing an image that risks getting confused with the anatomy, while the most recent translation oddly gives the most old-fashioned idiom, “don’t know a fig.”

Advertisement

Where two translations have a “Besides,” and one a “What’s more,” the other has nothing. One translation introduces a “sir”—“No, sir,” “Well, sir”—while the others do not; is it possible that all the other three translators would eliminate this “sir” if it were there? And why do two translators offer interesting nuances in this sentence: “you’ll probably not see fit to understand this,” “you will certainly not be so good as to understand this,” as if understanding were a matter of disposition rather than intellect, while the other two just give “you probably will not understand”?

There is simply no end to drawing fine distinctions between translations, discussing them in relation to the original and the cultural setting of the language of arrival, or their own internal consistency. Yet, all four of these translations are recognizably the same text. And Dostoevsky’s main stylistic strategies emerge powerfully in all of them, above all the narrator’s pleasure in parading his own perversity, his habit of qualifying everything he says in unexpected ways, of undermining received ideas (is it really superstitious to respect doctors?), of engaging, challenging and mocking the reader, and so on. Indeed, the more translations we have, the more we appreciate how overwhelmingly the text depends on Dostoevsky’s unique authorship. Does it make sense, then, to talk of the translator’s “co-authorship”? Why does translation have to be likened to something it is not? One might argue, of course, that Dostoevsky being long dead and his work out of copyright, the publishers could afford to pay a royalty since they are not paying one to the author. But that is a practical rather than a conceptual issue. Four translations of almost any text, ancient or contemporary, would yield the same results.

Some days after our meeting in Berlin, Ruth Keen emailed me the results of a questionnaire on earnings conducted by the German Translators Union. Five hundred ninety-eight people had responded and there were plenty of intriguing statistics: that almost 60 percent of books translated had come from English, for example; that though around 80 percent of translators were women, men tended to earn about $1.10 more per page; that work considered difficult was paid only marginally more per page than work considered easy (this despite the fact that the extra time taken over a difficult text might amount to a multiple of two or three, or even ten). But most of all, having presented a battery of statistics on royalties, the report lamented that low sales and high thresholds before royalties kicked in meant that it was extremely unusual for translators to benefit from them.

Where do these reflections leave us when it comes to pay and recognition for the wonderful work translators do? My own feeling is that the problem is less difficult than everyone pretends; that it surely would not be impossible to bring together editor, translator, and, say, an expert in translation from this or that language to establish how demanding a text is, how much time will be involved in translating it, and what would be a reasonable payment for doing so. Perhaps it is time for translators and translators’ associations to focus on putting such arrangements in place, without getting bogged down in the vexed question of authorship and royalties.