A month or so after the German-American artist Josef Albers died in March 1976, his wife, Anni, handed me a cracked leather case bulging with keys that belonged to him. She said we must drive to New Haven, about fifteen minutes from where the Alberses lived, to see if one of the keys would unlock a storage room used by Josef.

We went together, in the dark green Mercedes that was the couple’s only significant material luxury, from their modest ranch house to a building near the Yale University Art Gallery that, when Josef was working on Interaction of Color, had headquartered Yale University Press. “I think Kerr gave Juppi space in the basement,” Anni explained, referring to Chester Kerr, who had been editor-in-chief of Yale University Press, and using the name reserved only for intimates of Josef, one which Anni, when feeling particularly affectionate, transformed into “Juvel”—“jewel” in German. Although Kerr and her husband had fallen out, she said, Josef had retained use of the space rent-free.

Anni explained that she had never been in the room; the steps down to the basement were too steep for her, and it was Josef’s private domain. But very often they would park out front, and while she waited in the car, Josef would go in carrying a painting and come out with nothing or, conversely, go in empty-handed and return with this or that under his arm.

There were about half a dozen steel doors in the basement, all locked. I tried each of the twenty or so keys in five of the doors, without luck. Then one key opened the sixth. I groped for a light switch. As if with a flash of lightning, I was in a treasure trove. The first thing I saw was an illustrated letter from Paul Klee to Anni and Josef. Then I recognized glass constructions from the Bauhaus. The room was airless and stifling, though, and Anni was waiting outside, so I turned off the light, locked up, and went back upstairs.

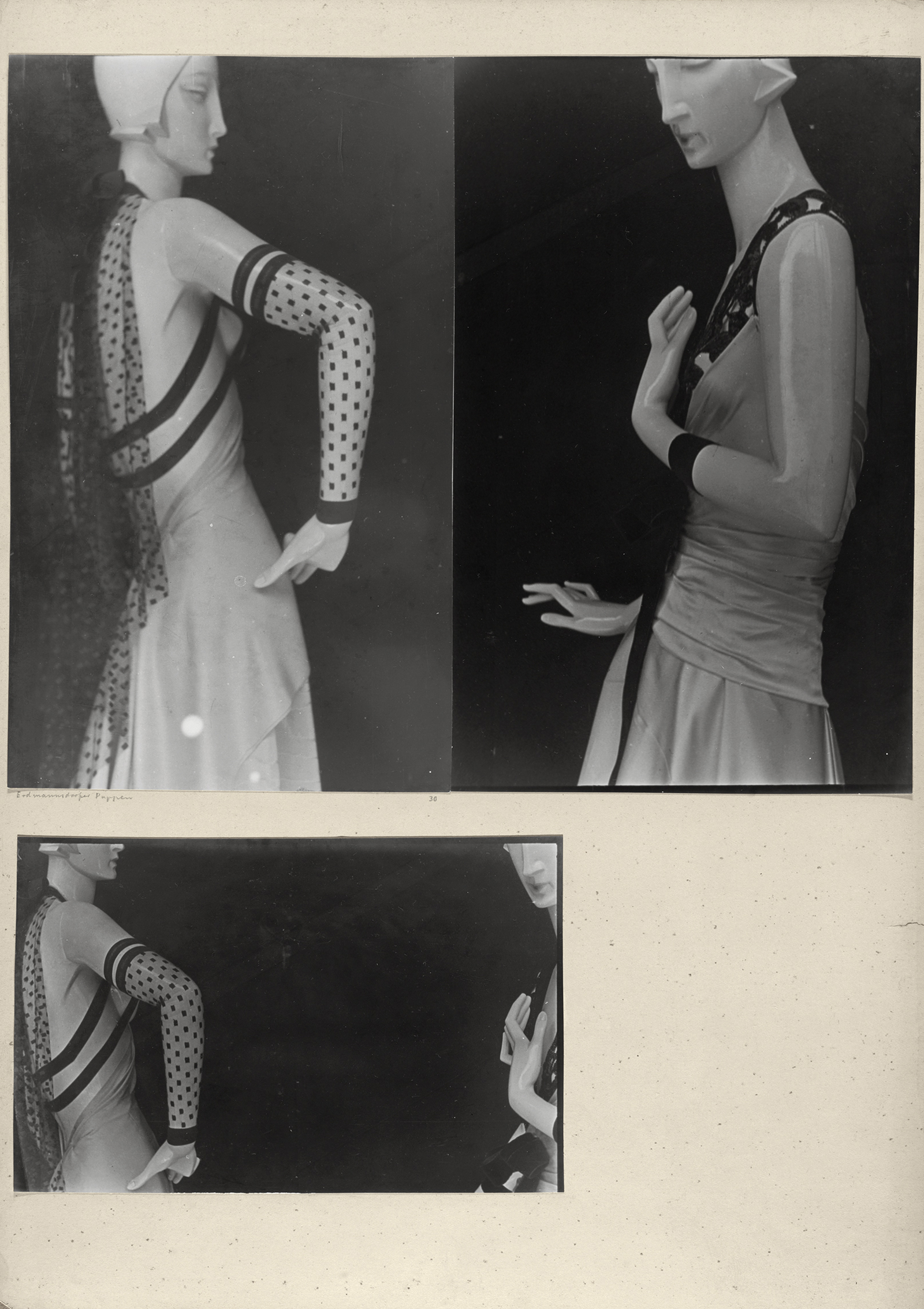

In the weeks that followed, I found piles of photo-collages, individual photographs, cans of film, and contact sheets. My wife, Katharine, carefully reorganized them and began the process of preservation. I knew Josef loved photography—he had spoken to me about visits from Henri Cartier-Bresson, Arnold Newman, Lord Snowdon, and Yousuf Karsh, and about his chance encounter with Irving Penn in the offices of Vogue—but he had never mentioned his own camera work, although he exalted his and Anni’s new Polaroid SX-70 as “a masterpiece of design, and so much better than bad painting.”

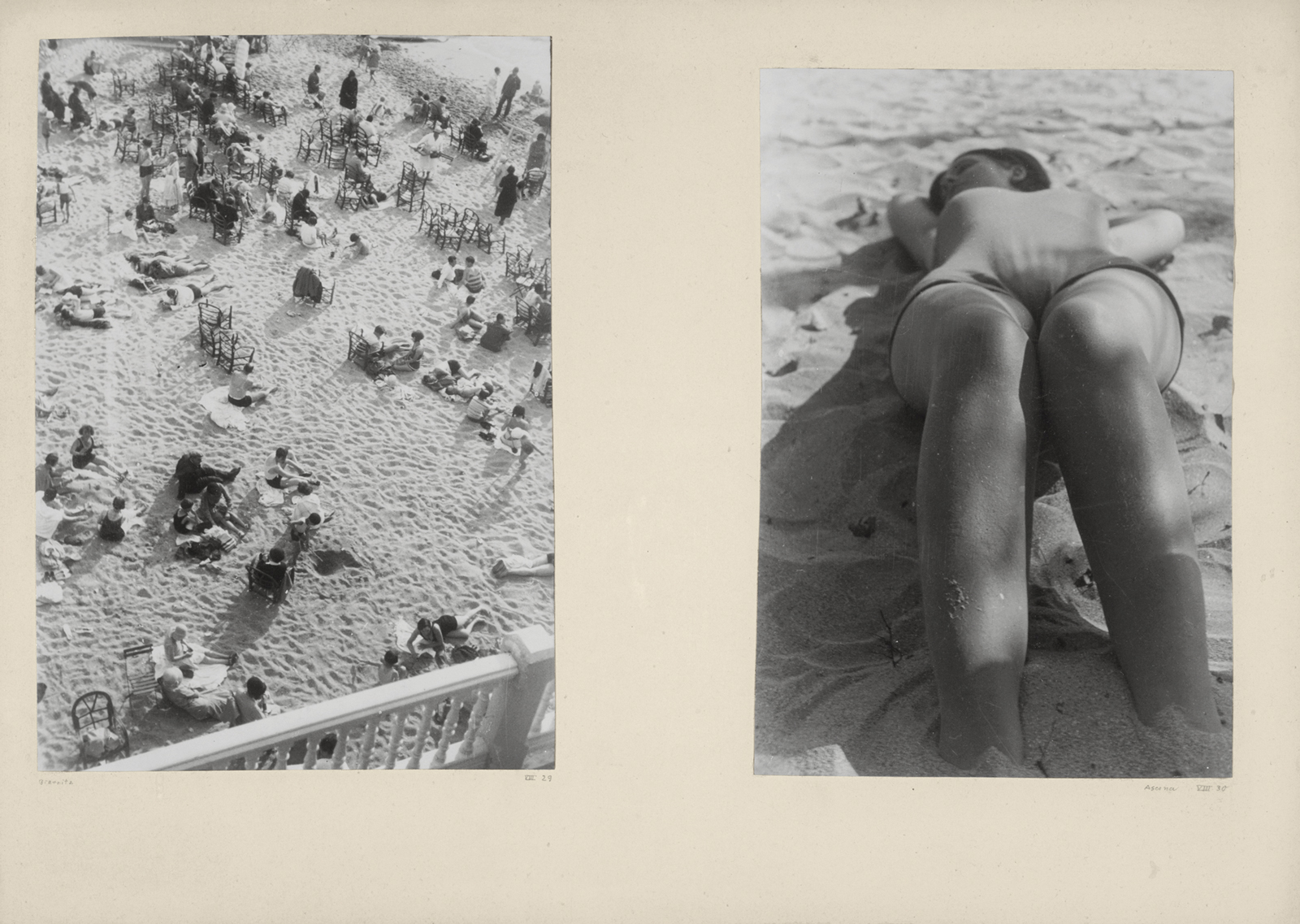

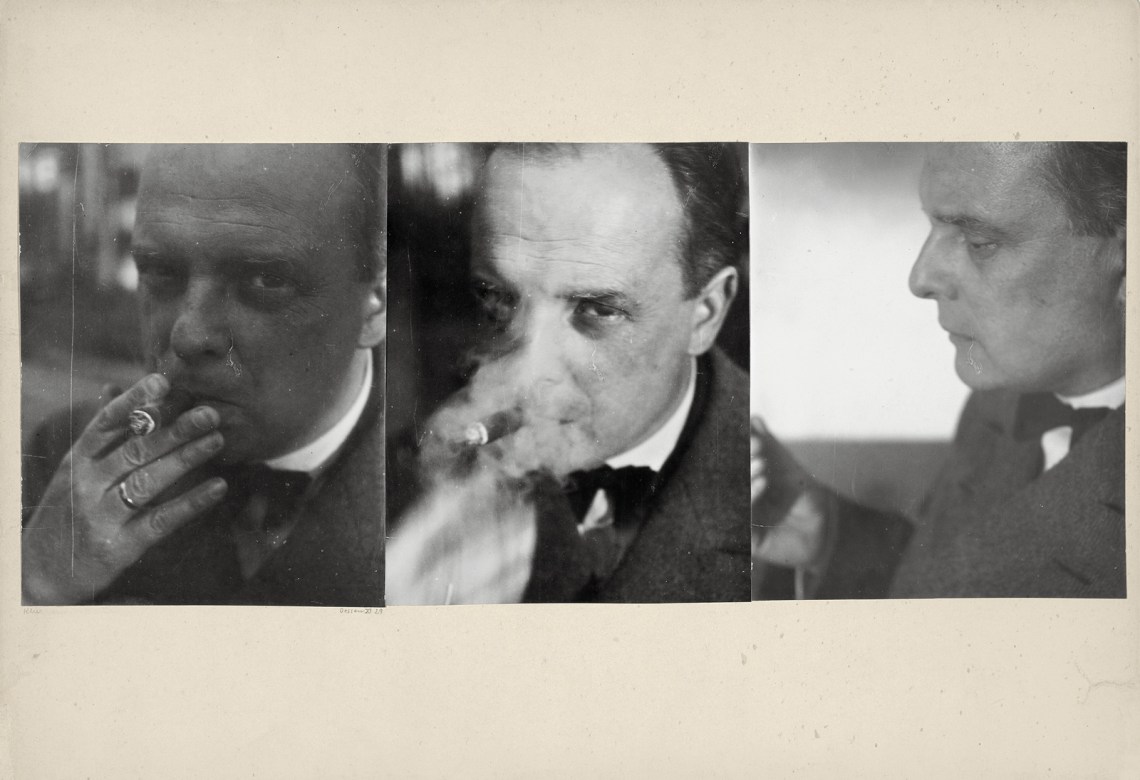

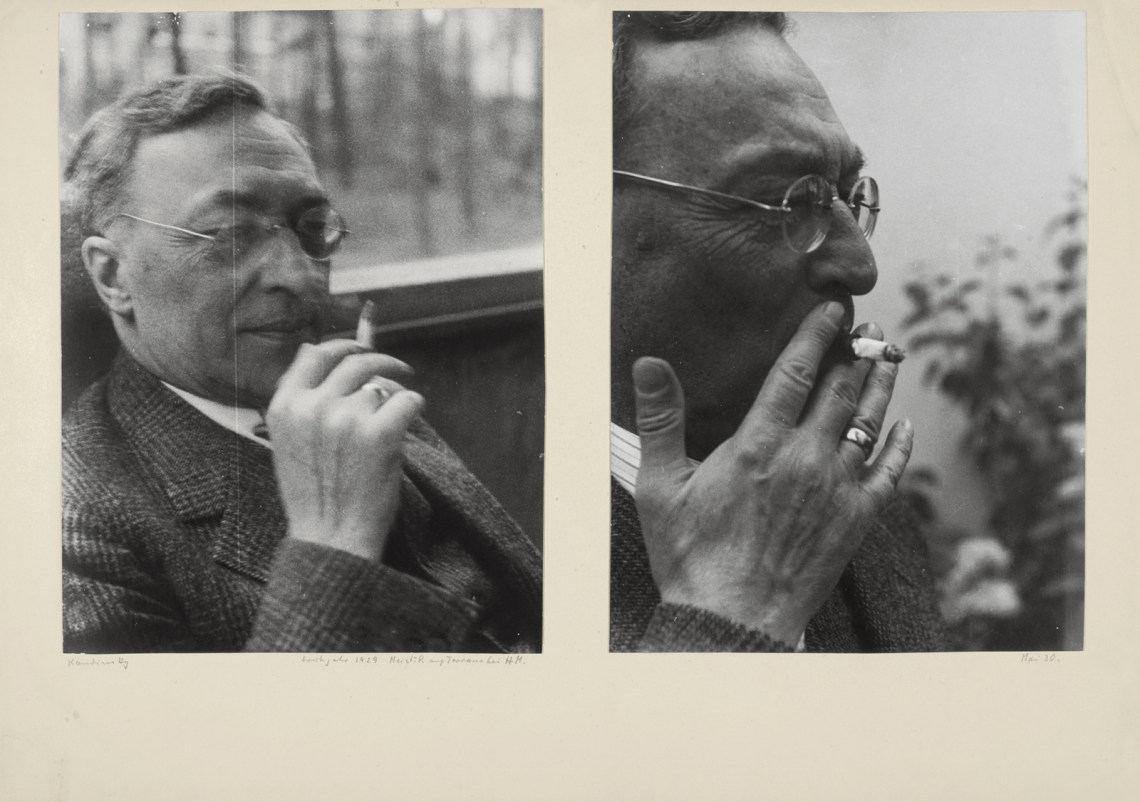

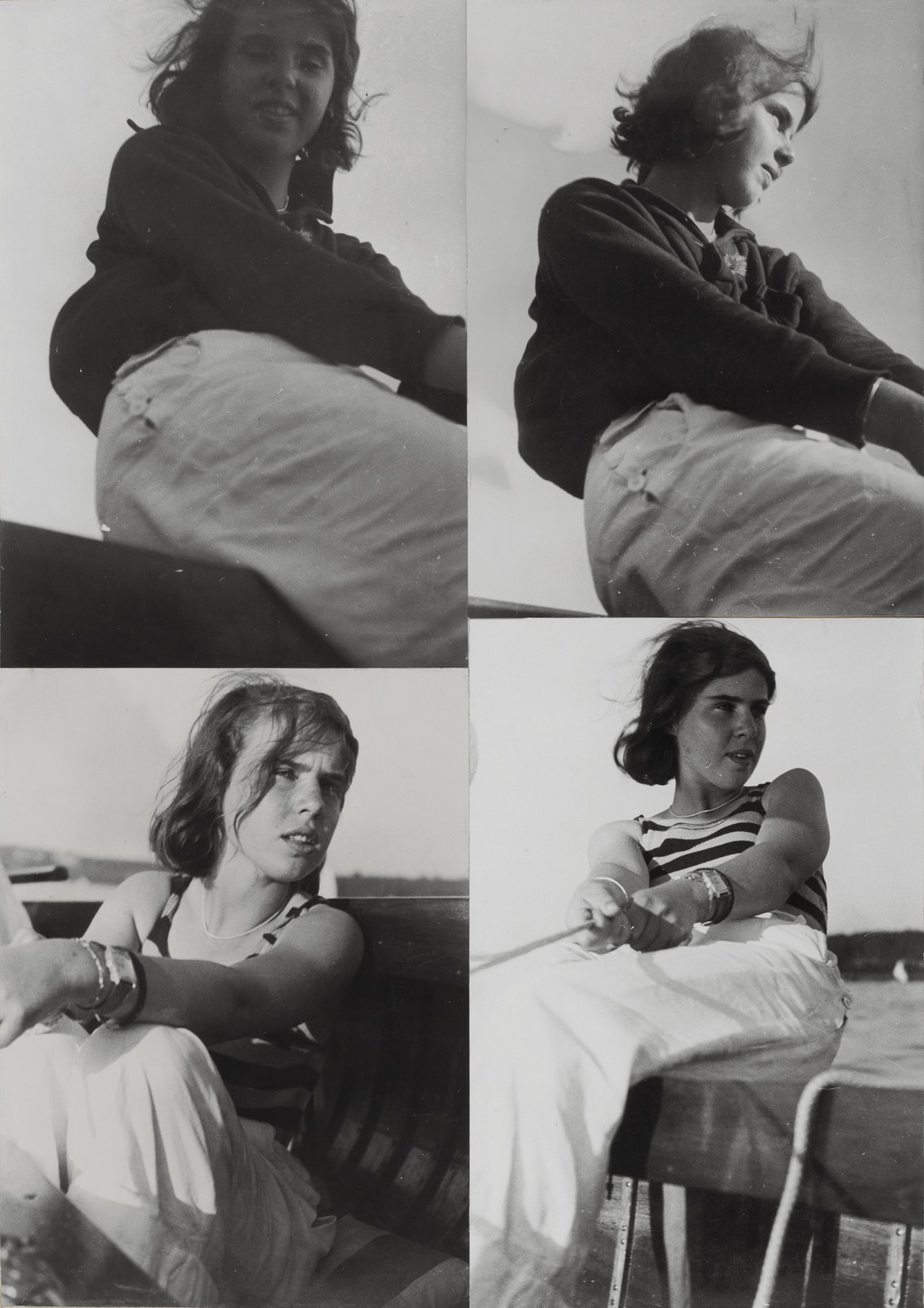

It was surprising not only that Josef was such a prolific photographer but that he had managed to save all this work. He and Anni fled Nazi Germany in November 1933 with few possessions. The following year, Anni’s father, a successful Berlin furniture manufacturer, had shipped some boxes to Black Mountain College, where Josef was teaching, but one can hardly imagine where and how Josef stored their teeming contents or got them to New Haven in 1950 when he became head of the art school at Yale. Amid the trove of photographic work were also more than a hundred earlier figurative drawings, including one of a naked couple dancing in frenzied ecstasy. Like the photographs of Bauhäusler cavorting on the beach, that drawing is intensely sensual, joyfully celebrating life’s pleasures.

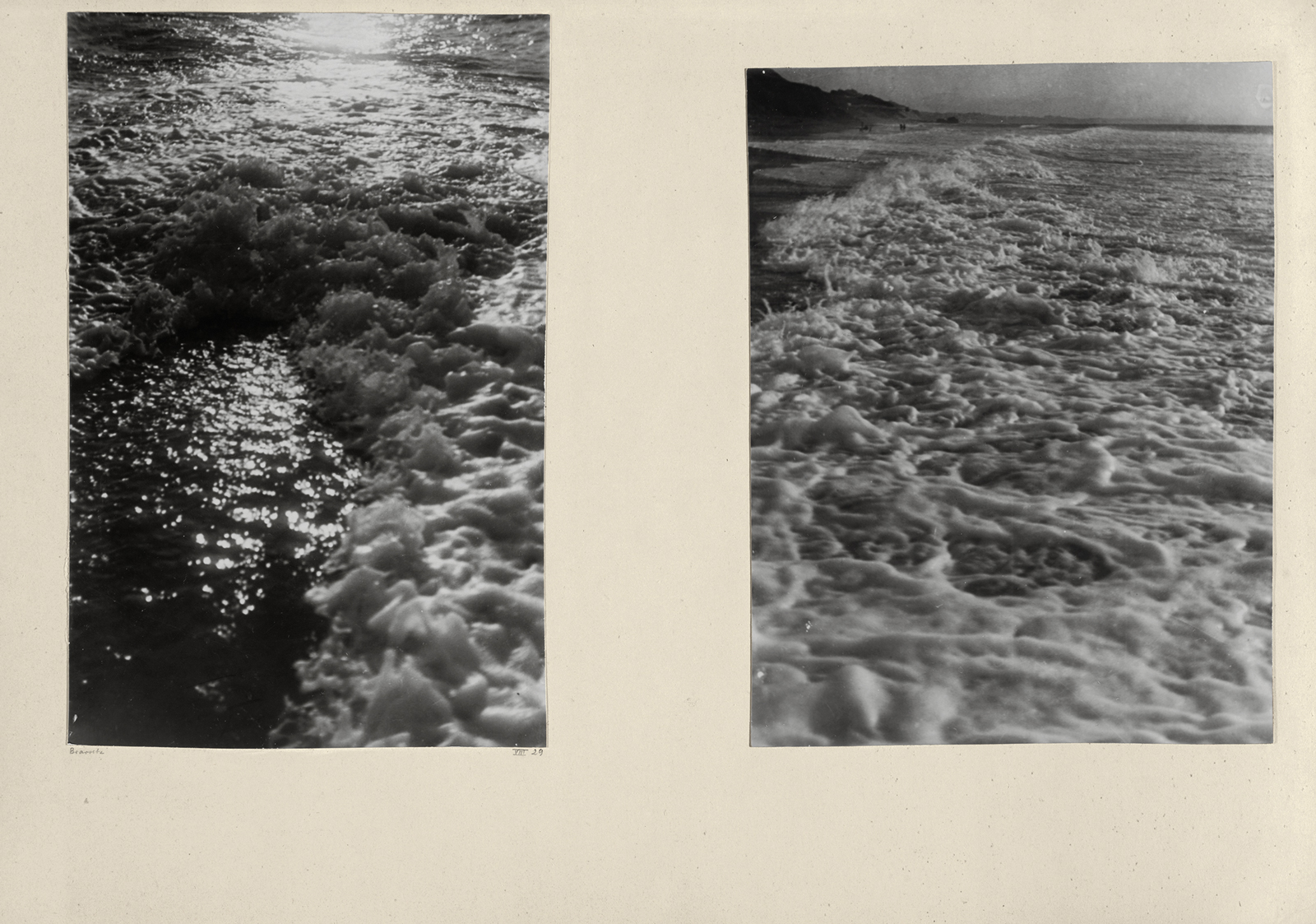

Josef was charming, as playful as he was certain of his beliefs, but I still felt as if I had found a Victorian grandfather’s erotica. And then I realized that the sheer love of living and seeing, an intoxication with the bounty of nature, overtly manifest in his photographs, is what permeates all of Josef’s work, including the more seemingly austere Homages to the Square for which he is best known.

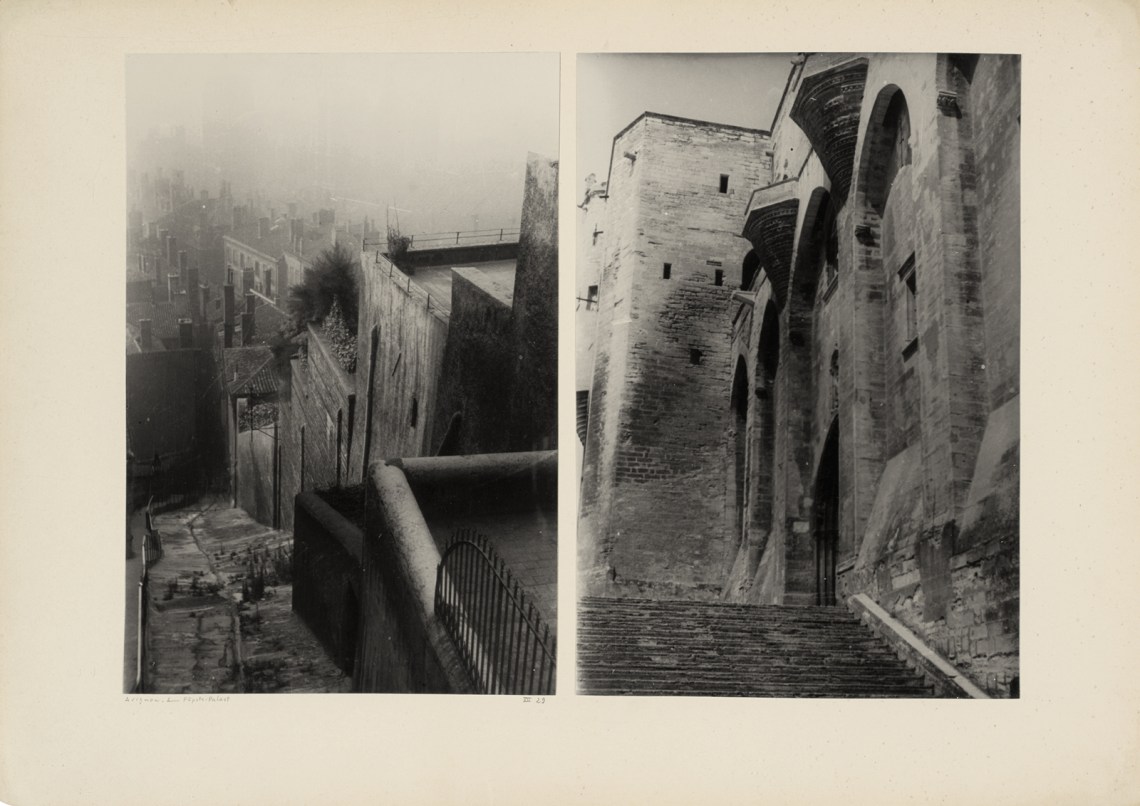

Josef assembled these photo-collages in the years when he was also constructing furniture, sandblasting glass, and teaching the nature of form and materials at the Bauhaus. Some of us will fasten onto the personalities that come alive in these photographs, and details like Paul Klee’s impeccable choice in the white cotton knit sweater he wore at a beach resort; others of us will see the lines left in the sand when the ocean recedes at low tide as evidence that the natural world was the greatest geometric abstractionist of all times. Josef’s camera work, and the intuitive yet precise way in which he juxtaposed photos large and small, reflect the desire that was his lifeblood: “to open eyes.”

Advertisement

“One and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through April 2. Adapted from the preface of One and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers, published by MoMA.