The first time I saw Hugh Edwards, he was entering Ida Noyes Hall at the University of Chicago in May 1962. It was pouring outside and he bounded up the short steps to the exhibition hall propelled by two wooden crutches, a conger hat sprightly tilted on his head. Inside was a small exhibition of photographs, part of the annual University of Chicago Festival of the Arts. Edwards was there to judge the pictures. Mine was a black-and-white print I had made myself, probably in the basement darkroom of the same building, a large space under a wide, sweeping staircase maintained by The Chicago Maroon, the school’s student newspaper.

I had heard of Edwards, who had recently been installed as curator for the large photography collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. A photographer friend, Brian Peterson, who had already shown his work to Edwards, had whispered to me, “He can give you a show at the Art Institute.” By the spring of 1962, Edwards had been responsible for more than twenty exhibitions, including a selection by Edward Weston and a survey of Alexander Gardner’s Civil War pictures. On a visit to the museum after we had met, he said to me, “Go downstairs and see that show.” It was Robert Frank’s first solo exhibit. People had complained about dust on the prints. “With pictures like that, who cares about the prints?” was his comment.

The picture I was showing that day had been made the previous winter in the desert in California near Yuma, Arizona. I had been hitchhiking outside Los Angeles and trying to get back to Chicago. When one of his six tires had a flat, the truck driver I was riding with pulled over in the Mojave desert. I needed to take a leak. Too shy to piss right there by the truck, I walked far off, up the side of a sand dune. When I turned around, the truck was before me and the sand dunes of the Mojave stretched beyond. That was the picture I made, and Hugh Edwards gave it the first prize.

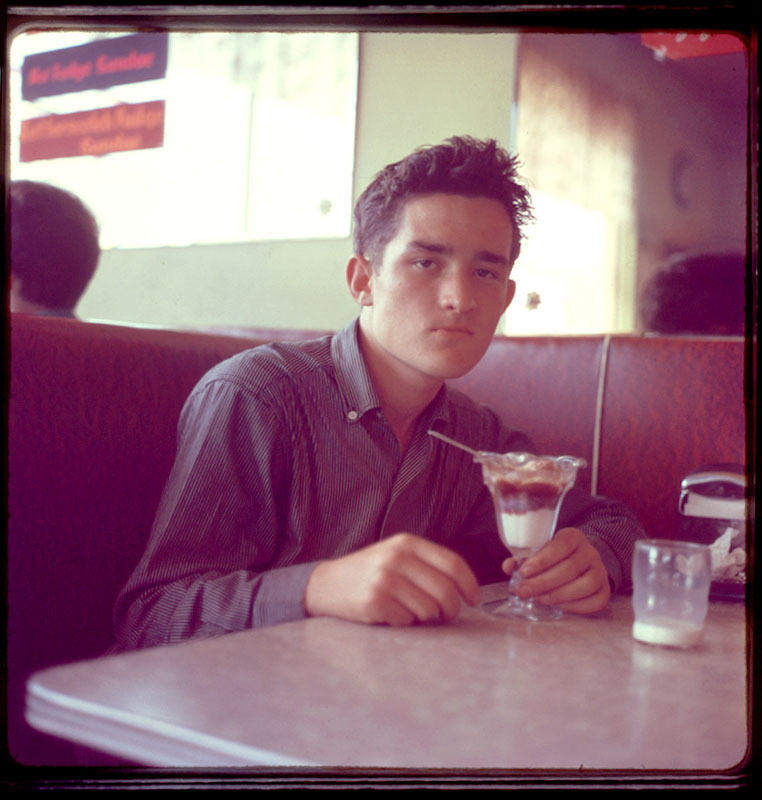

I would know Edwards for the next twenty-five years. That March I had just turned twenty. The winter before, my classmate Bernie Sanders had led a sit-in—the first carried out in the North—inside the University of Chicago’s administration building. By then, I was the campus photographer, making pictures for the yearbook and selling copies to the alumni magazine. I recall taking pictures at the sit-in and thinking that it wasn’t the real thing. The real action was in the South.

A few months after meeting Edwards, I hitchhiked to Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River flows into the Mississippi. There I met John Lewis, who had come up from Atlanta as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and had come to Cairo to help organize demonstrations. That summer in Cairo I became caught up in the movement, went further south, ended up in jail with Dr. King, and came back to publish my pictures in the Maroon. During the rest of 1962 and 1963, I regularly rode my Triumph down to the Art Institute, where I had the privilege of parking my motorcycle inside the loading dock at the north side of the museum and walking in through a side entrance. I was going to see Edwards and show him my pictures.

*

Hugh Edwards was born in Paducah, Kentucky, in 1905. His father was an engineer on the railroad. When Hugh was an infant, he was stricken with a bone disease that left him unable to walk. He spent part of his childhood being wheeled around in a cart. When he was in grade school, there was a lynching in Paducah, something that horrified most of the community, he told me. The next morning, when Hugh lifted the wooden top of his school desk and reached inside, he felt something wet. It was a portion of the victim’s skull, placed there by students as a joke. Once, as I showed Edwards the pictures I was making for SNCC of the movement in the South, he said, “What are they trying to do? Start the Civil War over again?”

I do remember almost everything Edwards told me but I wish I remembered more. His great uncle fought in the battle of Shiloh and took the family slave with him. They walked from Paducah, Kentucky, to western Tennessee, where the battle took place, and Hugh’s uncle was hit in the head with a musket ball. He survived, and as a child Hugh was able to lay his little finger inside the crease in his uncle’s skull. That story is probably as close as I will ever get to the Civil War despite all the books I’ve read about it, including the three volumes of Shelby Foote that Hugh Edwards told me to read.

Advertisement

In the 1930s, during the Depression, his parents enrolled him as a music student at the Art Institute. He would be associated with that building until he died. When we met, he was associate curator of prints and drawings. His predecessor, Peter Pollack, had begun a photography collection there, partly based on a large donation of prints by Georgia O’Keefe of Alfred Stieglitz’s work. (The other half of Stieglitz’s collection went to the Met.)

To me, a child of immigrants, Edwards seemed so American. He wore a tweed jacket and had a Southern accent and an almost maniacal way of laughing, usually at his own jokes. And he seemed almost exclusively interested in America, even though he was self-taught in a number of languages. Once, when I asked where he got his ideas, he said, “From French literature.”

My father, Ernst Lyon, had come to America from Germany about the time that Hugh reached Chicago from Kentucky. His ophthalmology office was high above Lexington Avenue and his client list included Stieglitz. The various apartments Stieglitz and O’Keefe lived in were close to the office, and he would arrive there on a bicycle wearing a black cape, my father said, “pretending to be poor.” A copy of Stieglitz’s photograph The Steerage hung in his office, a gift from Stieglitz to Norma Swernof, my father’s secretary. My father was also an amateur photographer and filmmaker and, in 1959, knowing that I was making a trip to Europe, he told me which camera to buy: a single lens reflex made in East Germany called an Exa. I bought it in Munich, and after taking the trolley to a suburb, made some of my earliest pictures inside Germany’s first concentration camp, Dachau.

As a student photographer, I quickly outgrew the Exa. I was using a Nikon F when I photographed Bernie at the sit-in. That was the camera I used when I hitched with the truck driver and made the picture that brought Hugh and me together. I had it with me in Cairo. Many of the early pictures I took in the South when I was twenty were made using a 105 mm lens on that Nikon F Reflex, something professionals call “a cheater,” because instead of walking across the street to fill up the frame with a 50 or 35 mm lens, you can take the same subject from a distance.

By the time I left the Civil Rights movement, I had vowed never to use the “cheater” again. I would work in my darkroom, usually set up in a bathroom, and print my pictures, mostly eight by ten inches, on Agfa #2 paper. When I had enough prints, I would put them in a box, get on my motorcycle, and ride to the museum to show them to Edwards. I would do that one way or another from when I met him until the day he died. When he did, I wondered whom I could show the pictures to. No one would ever replace him. Hugh Edwards was the greatest curatorial figure in late twentieth-century photography. Meeting him on that rainy day in Ida Noyes Hall would change my life forever.

*

They didn’t know it in New York, because New Yorkers like to write about New York, but Edwards ushered in what is known as the Golden Age of Chicago Photography. He expressed himself mostly in conversation and through the photographers he chose to exhibit. Despite saying that he hated to write, that it was a torture for him (he left almost no published writing), he did leave a trove of letters, often to photographers, and he kept carbon copies of many of them. He talked a lot, much more than I do, and I would sit late into the night listening to him pontificate in his small Hyde Park apartment. One time I took out a joint and started to smoke it. We looked at each other, the young stoner and Edwards, who, never at a loss for words, said, “The only thing about it is, it’s not natural.”

I longed to ask him, but never did, how he knew what was good. How had this man discovered Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson, and so many other photographers? Why did he refuse to recommend Diane Arbus for a Guggenheim, telling her that she already had enough supporters? In one of his letters, not written to Frank or Walker Evans but to a photographer named Bill Endres, he wrote, “I am very self-centered, I suppose, and what I like—no matter what—is anything that makes me feel right and glad that I am alive.”

Advertisement

He loved my pictures of motorcycles, and one afternoon in May 1963, after I visited him at the museum, he wrote me a letter. He said that for the first time I had stepped out from between the subject and the camera, and so “the pictures revealed more about you than anything else you had ever done.” I had no idea what this contradiction meant and spent about five years trying to figure it out. At the end of the letter, he threw in, perhaps in a reference to my budding interest in the Civil Rights movement, “Thank God for no social messages.”

Three years after he wrote that letter, I got on the back of a motorcycle driven by a member of the Louisville Outlaws. Across from us another Outlaw with long dark hair was mounting his Harley. I asked him to leave off his helmet, which he strapped on the handlebars of his panhead. We were going to make pictures as we rode across one of the many bridges that separated Louisville from southern Indiana. This time, the Nikon F, my workhorse, had a 35mm lens. As we approached the bridge, me seated and turned sideways behind another Outlaw and watching the pavement streak past beneath us, I remember deciding to leave some space in front of him—that was where he was going—and then making a single exposure.

Edwards wanted me to do a book, and it was the pictures of bike riders that I kept bringing him. At one point, I took the pictures to Aaron Asher, an editor at Viking. “This isn’t a book,” he told me. “It’s a box of photographs.” I decided to make a text with a tape recorder. At the time, I thought of the camera as a machine “of presentation,” as Hugh had written, and the recorder was a similar machine. I decided that I could simply record what the bike-riders had to say and edit it slightly. I thought of myself as a “realist”—meaning that I was making my art directly from reality—but when I mentioned this to Hugh later, he told me I didn’t know what I was talking about. There was something called Realism in the arts, and it was not what I was doing.

One day I asked Hugh how I would know if I was done with my project. I had gone to every meeting and every motorcycle rally for over a year and drunk so much beer it was coming out my ears. “I suppose when you have photographed every aspect of it,” he said. When I brought him the text all neatly typed and edited, he declined to read it, saying, “I’d rather read it when it’s published.”

By the time I saw the first copy of The Bikeriders, I had left Chicago for New York and then for Texas, where I’d started taking pictures in the Texas Department of Corrections. I had dedicated the book to Hugh Logan Edwards. In the first copy I received in the mail, seven pictures were out of register and many didn’t have much ink on them. I was distraught and wrote a long complaint to my editor. Then I mailed the book to Hugh. “I will always associate you with this book,” I wrote him.

The photography you introduced me to has enveloped me and my life in a way I never could have imagined. And with it I have grown into all my joy and pain. Certainly this book is not the one you suggested. I am hoping if a second edition is printed that some of its grosser errors will be corrected. I hope that they do not disturb you so much as to nullify my intent. You not only encouraged my photography but seemed to awaken a vision in me from which I will never recover.

In 1976 I returned to the Art Institute to judge a student art show. Standing in the hall with Hugh, we were approached by Archie Allen, then the head of the school. “You know what you are?” Allen asked me. I shook my head. “You are a stone documentarian.” Perhaps he was right. In 1973 I had returned to Chicago with a tape recorder, determined to make a hundred tapes of Hugh speaking about his life. He didn’t want me to make any recordings, saying that he preferred not to be “etched in concrete.” Later, when I mentioned his objections, Hugh said, “That’s ridiculous. There is no such thing as ‘etched in concrete.’” And for the next three days, I came over and sat with him; and as he spoke, the tape recorder sat between us on his coffee table.

*

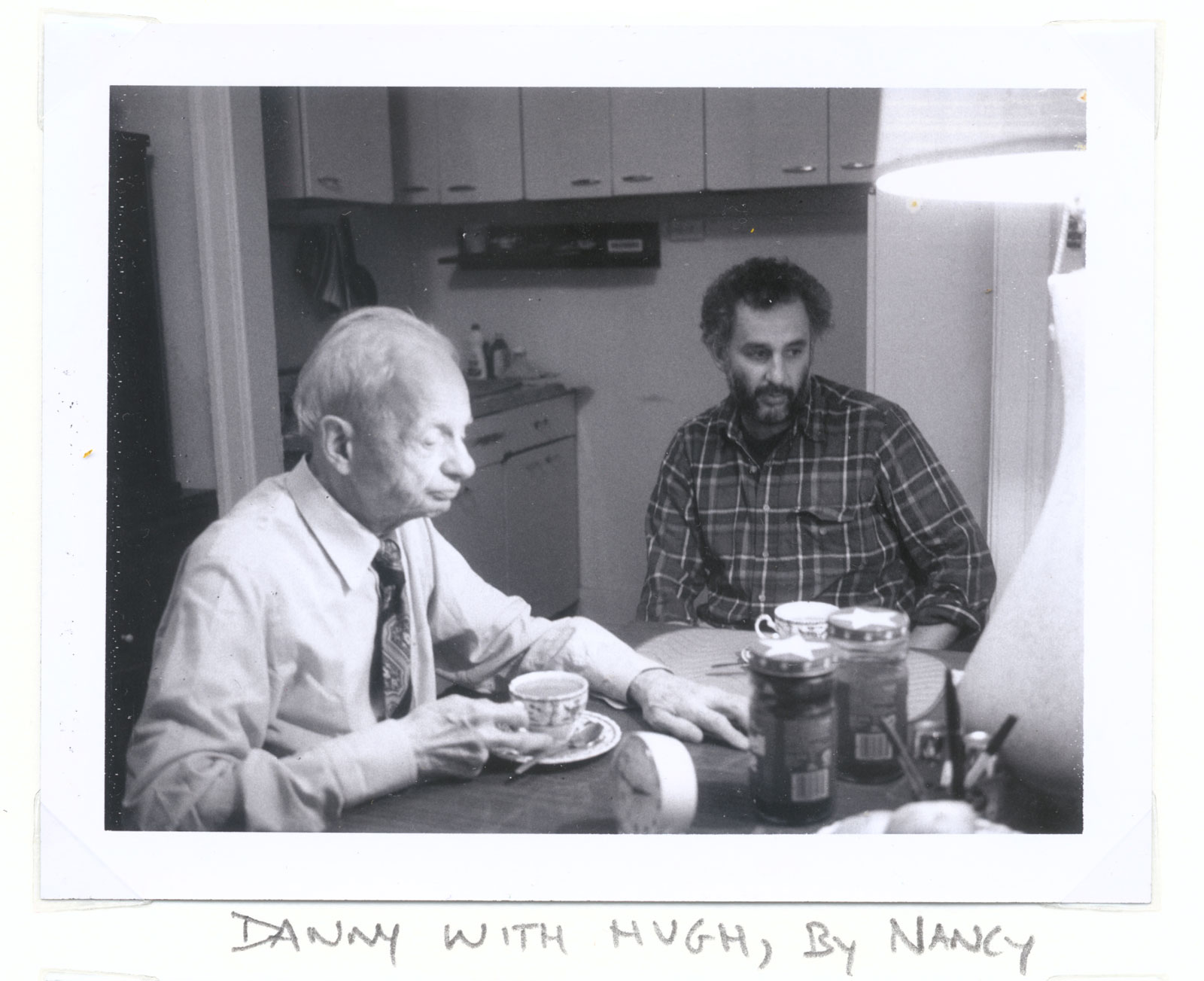

My last visit to Hugh was about ten years later, and in his new studio apartment overlooking the lake, he tried to return my photographs. I had been sending him prints for years, ever since I knew him. When he asked if I wanted them back, I knew what that meant. I wanted him alive, and so I said no. We made pictures with my Polaroid and my wife Nancy made a picture of Hugh and me together, the only one that was ever made. Then Nancy and I returned to our lives on a small house on the Peconic Bay, and I would speak with Hugh by phone. One time, my daughter Gabrielle played the flute for him.

In the summer of 1986, we were heading to Canada with the four children in the back of a station wagon when I tried to reach him. His phone had been disconnected. I was horrified. When we reached the fishing camp in Quebec, I tried to reach him again from a pay phone in the office. Hugh had been moved out of his apartment. No one had told me. Eventually I managed to track him down to a nursing home on the north side. He was there but unable to come to the phone. I tried calling Hugh every day, and each time I was told he couldn’t talk. Finally a woman—a nurse or a caretaker—came to the phone. I could tell from her voice that she was a black woman from the South. “Was he a friend of yours?” she asked. “I am so sorry to have to tell you this.” Hugh Edwards was dead.

When the curator David Travis cleaned out Hugh’s apartment, he had the good sense to make a black-and-white photograph of each wall, in every room. He sent me a set of the prints and I have put them in my albums. When I put his letters on my website, I also put out a dozen of Hugh’s best photographs, copied from the original chromes that David loaned me after his death, color pictures made with his Rolliflex in the Harvey roller rink in the early 1950s. Hugh told me he stopped making pictures after he saw the photographs of Robert Frank.

Recently David told me that he had discovered large-format black-and-white negatives that Hugh had made before he stopped. Shouldn’t those be here in the Art Institute? Shouldn’t any pictures, any letters Hugh left, shouldn’t everything that still exists of Hugh’s and might tell us something about this great man, be archived and made available, preserved for the future? Years ago, I learned that someone at Esquire had once wanted to write about Hugh. Apparently, the journalist asked him why he didn’t take photographs himself. “Why should I?” Hugh answered. “Other people take them for me.”

Adapted from a lecture delivered at the Art Institute of Chicago on October 27, 2017. For more information about Hugh Edwards’s life and career, visit media.artic.edu. For a complete set of Edwards’s pictures and more of Danny Lyon’s writings, photographs, and films, visit bleakbeauty.com.