Years after the event, the American survivors of the battle of Balangiga would recall the church bells ringing. The soldiers of the 9th Infantry Regiment said the bells tolled during a surprise attack by rebels in the port town of Balangiga in the Philippines. The year was 1901, and the United States was tackling an insurgency in its newly acquired territory. The Philippine-American war, though soon forgotten, cost the lives of some 4,374 Americans. Forty-eight US soldiers died at Balangiga, America’s worst military defeat since the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876.

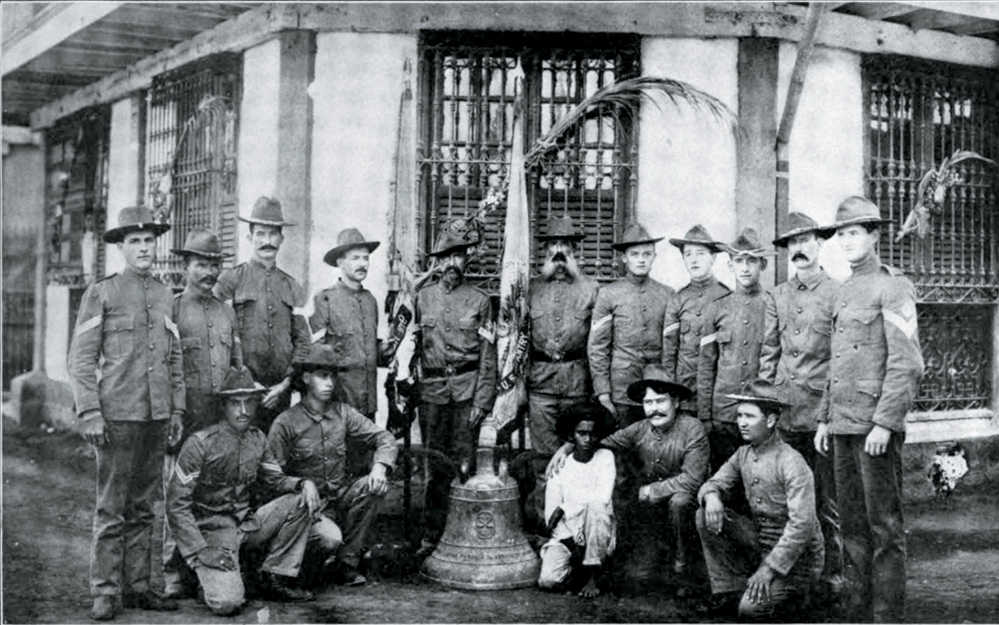

To commemorate their lost men—or perhaps to avenge them—American troops brought the three bells of Balangiga home with them. Over the next century, the bells passed through various military bases. Two are now in Wyoming, and one is on an army base in South Korea, displayed to memorialize the battle.

When President Donald Trump travels to Asia this November, he will meet with the president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, who recently called for the return of the bells. Veterans’ groups and some lawmakers, notably from Wyoming, argue strongly against such a concession. For G. Michael Schlee, the chairman of the American Legion’s National Security Commission, the memorial honors “the ultimate sacrifice paid by the soldiers who died in battle.” Others question the US military’s ownership right. Stephen Sheppard, dean of St. Mary’s University School of Law, wondered, “Do we have the right to take their private religious property to honor the troops who died before we stole the bells?”

At the heart of the dispute is the question of how we ought to remember a little-known, inglorious war in which American and Filipino troops alike committed acts of valor and war crimes. “One of the fascinating and vexing characteristics of symbols like these monuments is that people want them to have a single meaning,” said W. Fitzhugh Brundage, a history professor at UNC-Chapel Hill. “The problem is the more important the symbol, the more likely there will be competing interpretations of that symbol.”

The conflict in the Philippines followed the Spanish-American War. Allied with Filipino revolutionaries, the US had defeated the colonial Spanish troops on the islands. But then, instead of granting the Philippines their independence, as the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo insisted had been promised, the US bought the islands from Spain for $20 million. The revolutionary forces rebelled but were soon defeated by US troops, and Aguinaldo was captured in 1901.

Like Iraq and Afghanistan a century later, however, a quick military victory led to a long, painful insurgency. The war officially ended in 1902, but fighting continued in the southern islands for the next decade. Estimates of the death toll in the conflict vary from 200,000 to 600,000.

The soldiers of the 9th Infantry, Company C, arrived at Balangiga on August 11, 1901. At first, they fraternized with the locals. Officers played chess with town leaders, and soldiers left their rifles to go to meals and church. About a month after arriving, though, the unit’s commander, Captain Thomas E. Connell, ordered his troops to arrest every able-bodied male and detain them in work camps. In a town that for years had suffered raids by slavers, Connell’s order was the “nail in Company C’s coffin,” wrote historian Bob Couttie in his account of the battle.

Filipino rebels streamed into the town. Hidden in women’s clothing, men carried coffins filled with bolos—Filipino machetes—into the church. On the morning of September 28, when the men of Company C racked their rifles in the barracks and left to eat corn beef hash at the mess hall, about five hundred men armed with bolos swarmed the town. US troops heard bells and the wail of conch shells, which was either the rebels’ signal to attack or a call for reinforcements.

Few soldiers could reach their weapons. Connell was caught jumping from a second-story window and was killed in the streets below. The attack, sometimes called a massacre, was over in twenty minutes. Of the seventy-eight men of Company C, forty-eight died and only three escaped without wounds; the survivors made off by boat up the coast.

After regrouping, US troops returned to Balangiga in force. They bombarded the town with cannons, and set it ablaze. The three bells remained in the ruins of the church. But the retribution did not end there. General Jacob Smith told his troops he wanted a “howling wilderness” and ordered any male over the age of ten killed. “I want no prisoners,” he said. “I wish you to kill and burn; the more you kill and burn the better it will please me.” Theodore Roosevelt, who was responsible for the conduct of the war in the Philippines for part of 1902, had earlier reflected on the justification for such harsh tactics. “In a fight with savages, where the savages themselves perform deeds of hideous cruelty, a certain proportion of whites are sure to do the same thing,” he said. In the reprisals for Balangiga, US troops are said to have killed as many as 50,000 Filipinos.

Advertisement

Not surprisingly, therefore, Filipino advocates regard the bells as a symbol of their country’s struggle against foreign invaders, and of the suffering that Filipino people endured. What happened to the bells, and how they wound up in Wyoming and South Korea, would be a mystery for decades, until efforts by Couttie, his fellow researcher Rolando Borrinaga, and a woman named Jean Wall. Growing up in the 1930s, Wall heard the story of Balangiga from her father, Adolph Gamlin, one of the survivors of the battle. She used to brush her father’s hair, and as she did, she could see on his head and running down his back the scars from where he was clubbed by rebels.

Couttie’s team traced the two larger bells to Wyoming, where soldiers of the 11th Infantry Regiment had taken them in 1904. The third, smaller bell followed the 9th Infantry first to Fort Sam Houston in Texas, in 1907, then to Fort Lewis in Washington, and finally to Camp Red Cloud in South Korea. There it hangs in a regimental museum with the words: “The people of Balangiga donated the bell to the regiment when it sailed for home on 9 April 1902.”

Today, that “donation” is disputed. On September 28, on the anniversary of the Balangiga attack, President Duterte said: “I hope that Congress of America will give President Trump the authority to return the bells to us.” He is expected to raise the issue with Trump on his trip.

In the Philippines, the war—and the atrocities—have not been forgotten. They have inspired movies, books, and a musical. The town of Balangiga even built a tower to house the bells. “When we talk to Filipinos in the Philippines and you mention the bells of Balangiga, you get a visceral reaction: ‘We want the bells back,’” said Sonny Busa, a Filipino-American graduate of West Point. “You’re going to talk about forty-eight American soldiers; what about 50,000 Filipinos?”

That doesn’t sit well with American veterans of the 9th Infantry, who see the Balangiga bell as a cherished relic. Returning the bells, they say, would be an affront to veterans and amount to an “apology” or “reward.” “Men fought and died in the Filipino campaigns,” said Dennis Smith, a 9th Infantry veteran from Upper Sandusky, Ohio. “They give us those lives back, then maybe we would consider it, but until then the bells can stay where they are.” After a plea from Wyoming vets at a national convention last year, the American Legion also moved to oppose any attempt by Congress to return the bells.

Yet there is recent precedent for returning similar war relics. The US Naval Academy and the Virginia Military Institute have both repatriated bells to Japan, and the military academy at West Point last year returned another bell taken from the Philippines. For Brundage, a history professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, military memorials—bells, flags, or monuments—often embody unresolved historical conflicts. Near his office is a statue of a Confederate soldier. It had been designed with one meaning in mind, Brundage noted, but as time went on, other perspectives entered the conversation.

“Bells that were taken from a site of a massacre that then prompted a retaliatory campaign… may be interesting or educational,” said Brundage, “but it’s not likely to leave someone uplifted or filled with patriotism.” In his view, a full and nuanced perspective on the bells requires acknowledging that they represent different things for different people—colonialism and war crimes for Filipinos, valor and sacrifice for American veterans. The Balangiga survivor’s daughter, Jean Wall, said that she was once against returning the bells. Today, her position has changed: she now believes the 9th Infantry should keep one bell, Wyoming should keep another, and the third should be returned to the church in Balangiga.

Will Trump and Duterte manage to match their perspectives on the bells of Balangiga in such a spirit of compromise? For both presidents, it would be a novel departure.