In March 1938, the Egyptian poet and critic Georges Henein and a small group of friends disrupted a lecture in Cairo given by the Alexandria-born Italian Futurist F.T. Marinetti, who was an outspoken supporter of Mussolini. Six months later, Henein, along with the Egyptian writer Anwar Kamel, the Italian anarchist painter Angelo de Riz, and thirty-four other artists, writers, journalists, and lawyers, signed the manifesto “Vive l’Art Dégénéré!” (“Long Live Degenerate Art!”) that would inaugurate Art et Liberté, a short-lived but influential artists’ collective based in Egypt that is the focus of an illuminating exhibition currently at the Tate Liverpool, in Britain, covering the years 1938–1948. Printed in Arabic and French, with a facsimile of Guernica on its reverse, the declaration was a direct challenge to the previous year’s Nazi-organized exhibition “Entartete ‘Kunst’” (“Degenerate ‘Art’”), which presented art by Chagall, Kandinsky and other modern artists, largely Jewish, that the Nazi Party deemed decadent, morally reprehensible or otherwise harmful to the German people.

Internationalist in orientation and opposed as much to fascist-endorsed art as to the Egyptian academy’s own nationalist-minded aesthetics that resurrected ancient symbols in the name of “Egyptianness,” the group declared that it was “mere idiocy and folly to reduce modern art… to a fanaticism for any particular religion, race, or nation.” Surrealism—in its rejection of tyranny in any form and by championing uninhibited freedom of expression—was a fitting counterpoint that the group believed could also be harnessed to bring about social change.

Though Art et Liberté was universalist in its philosophical convictions, the writing and visual art produced for the group’s five exhibitions and multiple publications—of which more than a hundred works and a similar number of archival materials are on display at the Tate—responded to specific Egyptian concerns. The Egyptian group’s work was no mere imitation of that of André Breton and his associates in the Parisian Surrealist scene, which tends to be regarded by critics as the movement’s one and true home. Rather, Egypt had its own distinct history and a style of Surrealism that, some argued, stretched into its ancient past. Painter, writer, and founding member of Art et Liberté Kamel el-Telmisany responded to public criticism of the group that it was contaminating Egyptian culture with European perversions: “Many of the Pharaonic sculptures… are surrealist… Much Coptic art is surrealist. Far from aping a foreign artist movement, we are creating art that has its origins in the brown soil of our country and which has run through our blood ever since we have lived in freedom and up until now.”

He and the painter and writer Ramses Younan criticized Dalí and Magritte as too premeditated, and the practitioners of automatic writing and drawing as insufficiently socially-engaged. They instead advocated for what they called Free Art, or Subjective Realism—an active mining of the unconscious fused with local imagery that would be familiar to Egyptians, but not fetishistic or nationalistic (a crime that Henein leveled against the Contemporary Art Group that succeeded Art et Liberté). The results were eclectic, as often Expressionist in style as overtly Surrealist, and occasionally humorous, such as Étienne Sved and Abduh Khalil’s irreverent parodies of Pharaonic symbols, which included transforming a pyramid into a chaise lounge.

Egypt in the late 1930s was a nation already deeply divided, with fascism’s growing appeal and Britain hindering any opportunity of national autonomy. As war approached, its economy stalled and poverty increased sharply as thousands of troops from across the Commonwealth descended on the country. The disturbed times found expression in images such as the bloodshot eye embedded within a mass of bulbous tentacles in Laurent Marcel Salinas’s Naissance (1944); the hirsute tree in Samir Rafi’s Nudes (1945) standing before faceless men and women either dead or running from an unidentifiable threat; and the naked girl, lost both to a pool of flames and a menacing giant, in Inji Efflatoun’s Girl and Monster (1941).

The presence of 140,000 soldiers in 1941 in Cairo alone caused a surge in prostitution in the capital, which was replicated in other major cities like Alexandria. This prompted a number of the artists shown here to depict emaciated and fragmented female bodies in paintings devoid of either eroticism or moralism. In Anwar Kamel’s untitled nudes, the women’s organs and bones appear visible through their skin as the earth seems prepared to swallow them. El-Telmisany’s Untitled (Wounds) (1940) is even more devastating: two figures, a naked woman and a clothed androgynous person, are bound together by each having a bloodied hand nailed to a tree, which may be a symbolic reference to the coarse violence of a transactional sexual encounter or the effects of sexually transmitted diseases. Others, such as Rateb Seddik’s haunting Liliane Brok et son orchestre aveugle (1940) and El-Telmisany’s Nude with Arm (1940) suggest raw corporeality in the paint itself, which, as in many Egon Schiele portraits, often appears, close up, like thinly-smeared feces or congealed blood.

Advertisement

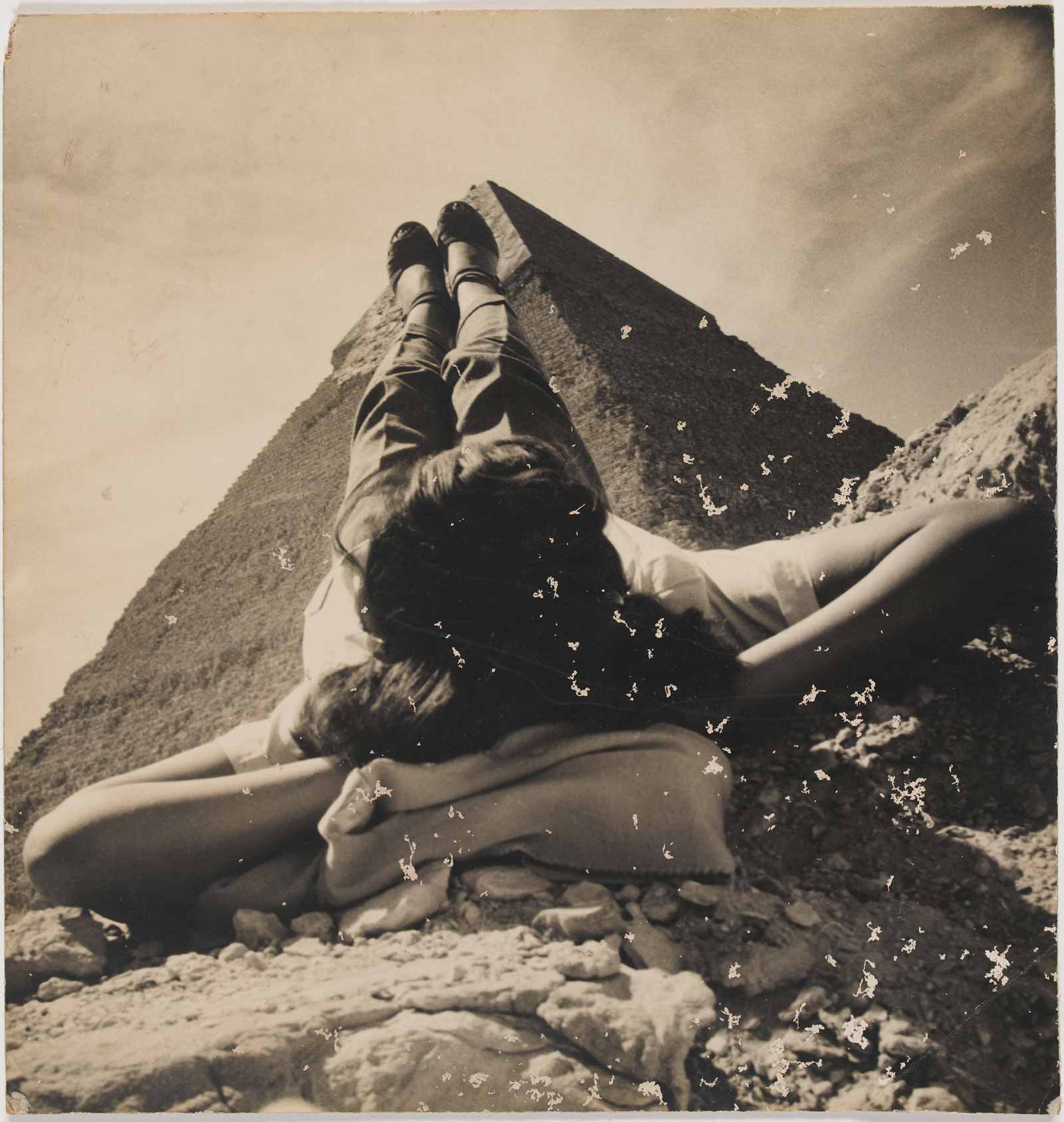

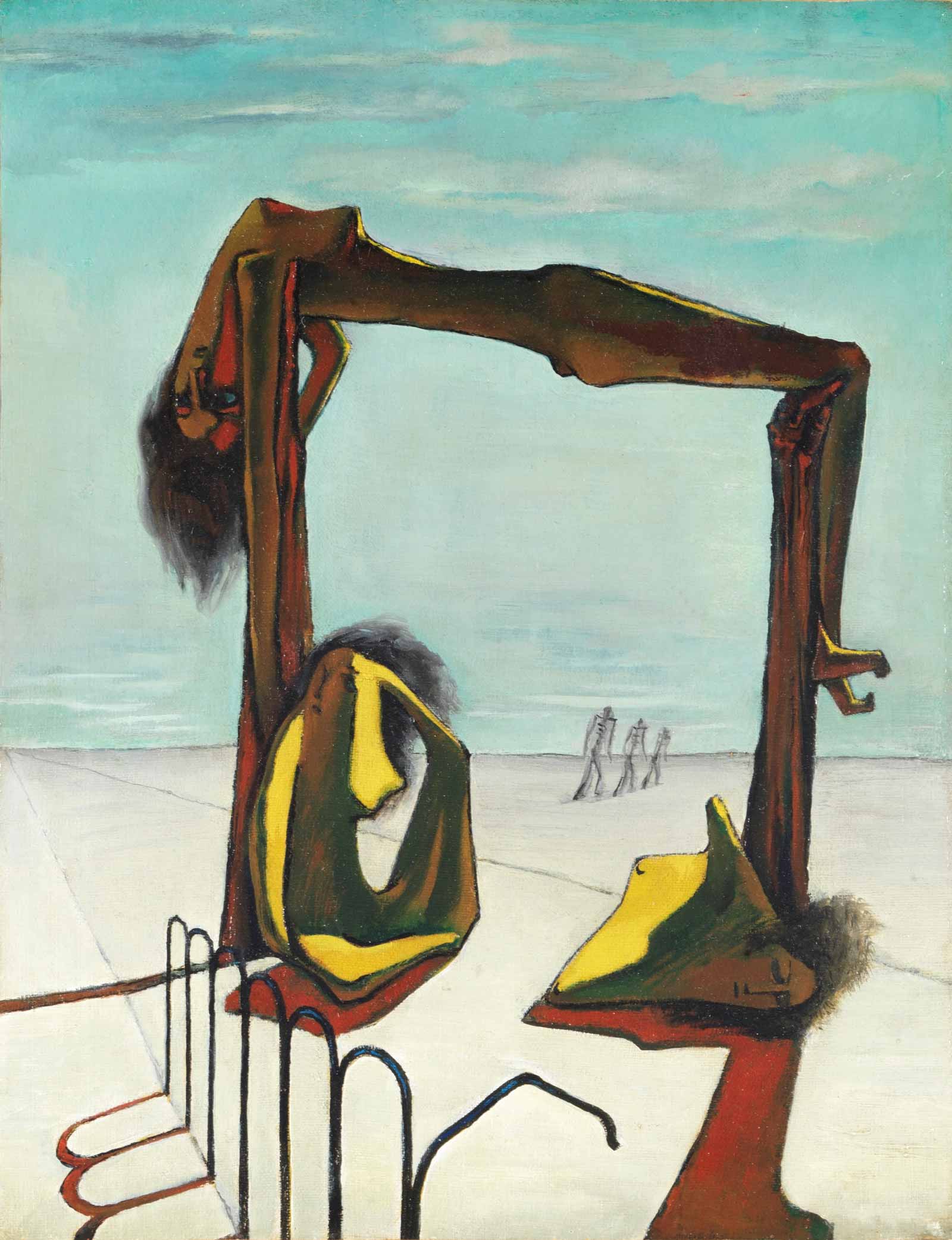

Younan’s 1939 untitled painting evoking Nut, the goddess of the sky, exemplifies Art et Liberté’s unique interpretation of Surrealism and subtle use of Egyptian cultural symbols. Though typically covered in stars and bent onto her hands with the world contained inside her arched body, Younan’s female figure looks contorted by physical abuse—perhaps at the hands of one of the figures walking into the distance of the De Chirico-esque empty, arid landscape. Younan’s figure lacks any trace of Orientalist exoticism and nativist myth-making, unlike British Surrealist Roland Penrose’s 1938 drawing Lee as Nut (modeled nude by Lee Miller, the American photographer, friend of Art et Liberté, and Penrose’s lover) and his follow-up Egypt (1939), in which Nut envelopes a dreamy and inviting desert scene—both of which hang nearby. Despite Penrose’s relationship with the group, these works convey the difference between those entranced, even unconsciously, by Egypt’s imagery and those, like Younan, who had no interest in romanticizing his country.

As curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath emphasize in their captions throughout the exhibition, Art et Liberté exemplified Surrealism’s global cosmopolitan character—after all, Dalí, Ernst, and many other prominent participants were not French. The group disrupted rigidity and calcification of any sort—whether of the Egyptian academy or of their fellow artists, such as those who, in 1946, founded the Contemporary Arts Group that Henein soon denounced as bolstering what he considered the tyranny of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalism. As Henein said of Nasser, “new Fascists in uniform” had taken control once again.

The anti-authoritarian ethos of the Art et Liberté group has lived on: the contemporary Egyptian graffiti-artist and muralist Ammar Abo Bakr, a critical voice during the 2011 revolution, paraphrased a quote from Henein in a recent piece in Berlin honoring the activist Shaimaa al-Sabbagh who, in 2015, was shot by police during a peaceful protest: “Revolution without despair nor hope.”

“Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938–1948)” is at the Tate Liverpool through March 18, 2018.