How to explain that the centenary of the man who was arguably Mexico’s greatest writer passed last year with barely a notice in the United States?

Juan Rulfo (1917–1986), rightly revered in Mexico and outside, is regarded as one of the most influential Latin American writers of all time. In the United States, too, he has been hailed, in The New York Times Book Review, as one of the “immortals,” and acclaimed by Susan Sontag as a “master storyteller” responsible for “one of the masterpieces of twentieth-century world literature.”

One reason for the surprising neglect of Rulfo today may be that his reputation rested on a slender harvest of work, essentially on two books that appeared in the 1950s. Yet it is no exaggeration to say that with the magnificent short stories of El Llano en Llamas (1953) and, above all, with his 1955 novel Pedro Páramo, set in the fictional town of Comala, Rulfo changed the course of Latin American fiction. Though his entire published work did not amount to much more than three hundred pages, “those are almost as many, and I believe as durable,” Gabriel García Márquez said, “as the pages that have come down to us from Sophocles.” Without Rulfo’s groundbreaking work, which blended the regional realism and social critique then in vogue with high-modernist experimentation, it is hard to imagine that Márquez could have composed One Hundred Years of Solitude. Nor, probably, would we possess the marvels created by Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, Rosario Castellanos, José María Arguedas, Elena Poniatowska, Juan Carlos Onetti, Sergio Ramírez, Antonio di Benedetto, or younger writers such as Roberto Bolaño, Carmen Boullosa, Juan Villoro, or Juan Gabriel Vásquez, among others.

What beguiled all these authors was Rulfo’s uncanny ability to give a lyrical majesty and distinct rhythm to the terse colloquial speech of the poorest Mexican peasants. That achievement may also explain why Rulfo is less esteemed in North America today, for it led to a literary style that was, alas, difficult to translate; the English versions of his work rarely preserve the magic of the Spanish original.

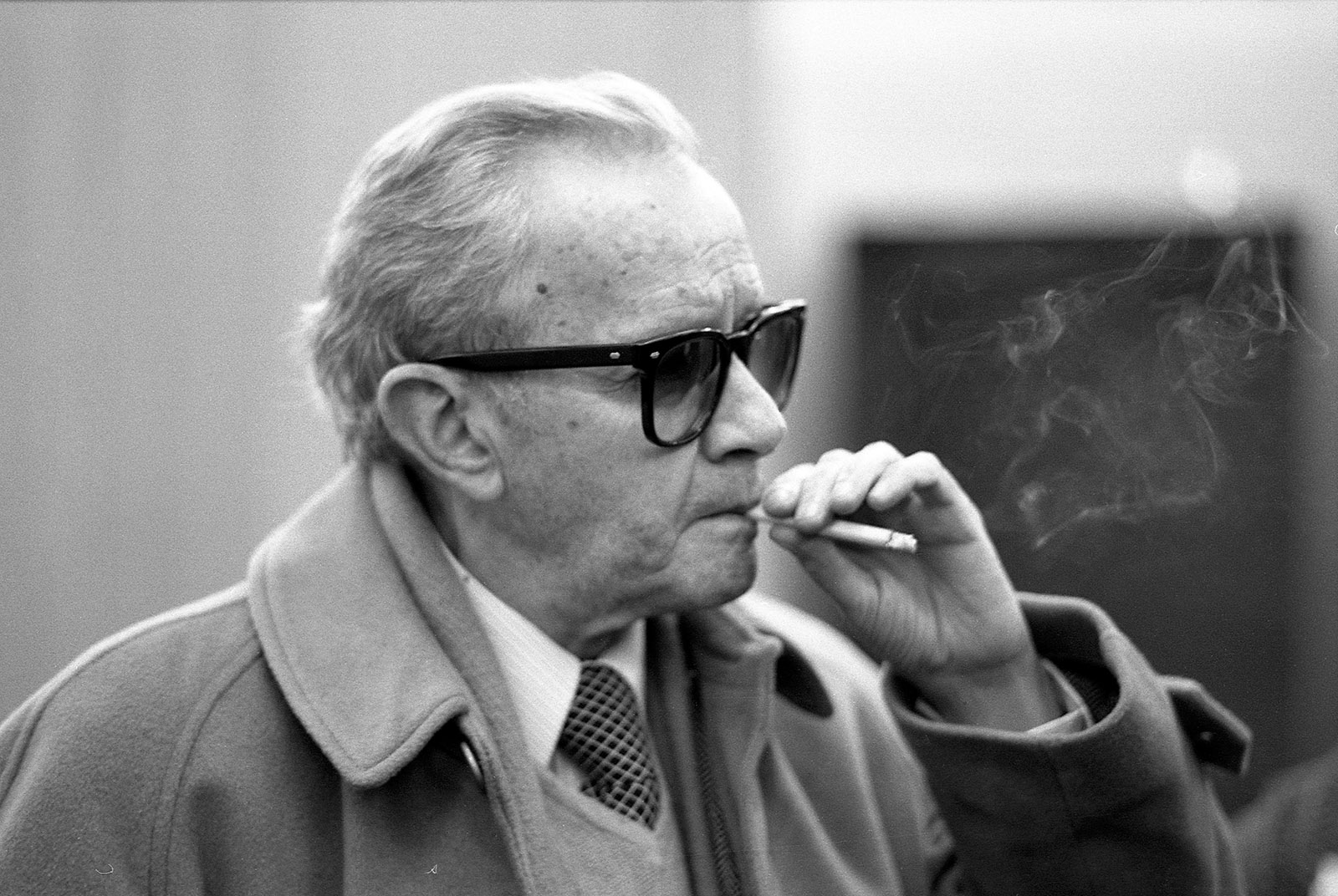

Another reason for Rulfo’s being overlooked may have been his own reticence and publicity-shyness, a refusal to play the celebrity game. Rulfo cultivated silence to a degree that became legendary. My friend Antonio Skármeta, the renowned author of Il Postino, told me that when he was about to be interviewed for a TV show one day in Buenos Aires, he saw Jorge Luis Borges and Rulfo coming out of the studio. “How did it go, maestro?” Skármeta asked Borges. “Very well indeed,” Borges replied. “I talked and talked and once in a while Rulfo intervened with a moment of silence.” Rulfo himself simply nodded at this account of his conduct, confirming the discomfort he felt at putting himself on display.

In the few interviews he gave, Rulfo attributed his reluctance to speak to the customs and reserve of the inhabitants of Jalisco, where he grew up—though other factors, such as the unresolved traumas of the author’s childhood, cannot be discounted. Jalisco, a vast region in western Mexico, has been the scene of an almost endless series of clashes and uprisings. Rulfo would carry with him all his life images of the carnage that followed the start of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Between 1926 and 1929, the young Juan witnessed the abiding fratricidal violence of his country, specifically of La Cristíada, the Cristero War. That popular revolt, an insurrection of the rural masses that was aided by the Catholic Church, began after the revolutionary government decided to secularize the country and persecute priests. (Readers may recall these events as the setting for Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory.) Jalisco was at the very center of the conflict, and the frequent military raids, volleys of shots, and screams kept the young Rulfo shut inside his family’s house for days at a time. Outside, men without shoes were dragged before firing squads, prisoners were strung up and hanged, neighbors were abducted, and the smell of burning ranches singed the air.

The terror was compounded when Rulfo’s own father, like the father of Pedro in Pedro Páramo, was murdered over a land dispute. A grandfather, several uncles, and distant relatives were also killed. Then Rulfo’s mother died, supposedly of a broken heart. In the midst of this mayhem, the future author found solace in books. When the local priest went off to join the Cristero rebels, he left his library—full of books the Catholic Index had forbidden—with the Rulfo family, paradoxically providing a vocation for a boy who would grow up to write about characters who felt abandoned by God, whose faith had been betrayed. Rulfo must have understood, somehow, during those years of dread, that reading—and perhaps, someday, writing—could be a form of salvation. Inspired by the ways that Knut Hamsun, Selma Lagerlöf, Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz, and William Faulkner had given expression to the people of the marginalized backwaters of their homelands, he found the means to describe the terror he had endured in the stories collected in El Llano en Llamas.

Advertisement

In these gems of fiction that English-language readers can enjoy in a recent, vivid translation by Ilan Stavans with Harold Augenbraum, Rulfo immortalized the derelict campesinos whom the Mexican revolution had promised to liberate but whose lives remained dismally unchanged. The men and women he described have been wedged into my memory for decades. Who could forget that group of peasants trekking through the desert to a useless plot of land the government had granted them? Or that bragging, drunken, fornicating functionary whose visit bankrupts an already starving pueblo? Or the idiot Macario, who kills frogs in order to eat them? Or the father who carries his dying son on his back, all the while reproaching him for the crimes by which the son has dishonored his lineage?

Crimes haunt most of these characters. A bandolero is tracked down for hour after hour along a dry riverbed by unknown pursuers. A prisoner pleads for his life, unaware that the colonel who commands the firing squad is the son of a man whom the prisoner killed forty years earlier. An old curandero (or healer) is corralled by a coven of women in black, bent on forcing him to confess to his many sexual transgressions against them. But, as always in Rulfo, the greatest crime of all is the destruction of hope, the orphaning of communities like the forsaken town of Luvina:

People in Luvina say dreams rise out of those ravines; but the only thing I ever saw rise up from there was the wind, whirling, as if it had been imprisoned down below in reed pipes. A wind that doesn’t even let the bittersweet grow: those sad little plants can barely live, holding on for all they’re worth to the side of the cliffs in those hills, as if they were smeared onto the earth. Only at times, where there’s a little shade, hidden among the rocks, can the chicalote bloom with its white poppies. But the chicalote soon withers. Then one hears it scratching the air with its thorny branches, making a noise like a knife on a whetstone.

This description not only gives us a distant taste of Rulfo’s style, but is also a metaphor for how he envisions his invented creatures: smears on the earth, hidden among the rocks, scratching the air in the hope that they will be heard—though it is only a remote, timid writer who listens and affords them the brief dignity of expression before they vanish forever. The bleak world depicted in Rulfo’s stories was on the verge of disappearing in the mid-1950s, with the migration of peasants to the cities and, from there, on to El Norte—victims and protagonists in a global trend that John Berger, for one, so movingly explored in his novels and essays. To read Rulfo in our times, when so many refugees pour out of Central America fleeing violence and thousands of lives are lost in Mexico’s ongoing drug wars, is to become painfully aware of the kind of conditions from which those people are escaping. Migrants who leave their own infernal Comala behind still carry inside its memories and dreams, its whispers and rancors, as they cross borders and settle into new streets. Rulfo’s fiction reminds us of why El Día de los Muertos, Mexico’s Day of the Dead, is more important today than ever as a link to the ancestors who keep demanding a scrap of voicehood among the living.

My own immersion in the hallucinatory world of Pedro Páramo and its evocation of the realm of the dead may illustrate how strongly Rulfo’s fiction affected Latin Americans and, particularly, the continent’s intellectuals. I first read Rulfo’s novel Pedro Páramo in 1961, when I was nineteen and studying comparative literature at the University of Chile; I was so mesmerized by it that, as soon as I finished, I started to read it over again. Years later, during a lunch with García Márquez at his house in Barcelona, he related that his encounter with Rulfo had been similar to mine. He had devoured Pedro Páramo, reading it twice during one long, enraptured night in Mexico City.

From its opening lines, the novel takes the reader on a mythical quest: its narrator, Juan Preciado, has promised his dying mother that he will travel to his birthplace, Comala, and find his father, “a man named Pedro Páramo,” who had sent the mother and her newborn child away and must now be made to pay for that betrayal. That journey, related in concise, poetic fragments, turns out to be even more disquieting than expected. Abundio, the muleteer who guides Juan down into the valley of Comala, acts strangely, suggesting that nobody has visited this place in a long time and that he, too, is a son of Pedro Páramo. The town itself, far from being the lush paradise of greenery that “smells like spilled honey” evoked by Juan’s mother, is miserable and mostly deserted. The only resident is an old woman, who gives the traveler lodging. Although nobody else appears in those parched streets, Juan hears voices that ebb and flow in the oppressive heat of a tormented night, phantom murmurs so stifling that they kill him.

Advertisement

As Juan descends into an eternal realm populated with the ghosts that suffocated him, the reader pieces together the parallel story of his father: how Pedro Páramo rose from the dust of a disadvantaged, backward childhood to become a caudillo whose toxic power destroys his own offspring and the woman he loves, finally turning the town he dominates into a burial ground swarming with vengeful specters. Juan himself, we gradually realize, has been dead from the start of his narration of these events. He is telling his tale from a coffin he shares with the woman who used to be his nanny and wanted to be his mother; we are struck with the petrifying knowledge that they will lie there forever in that morbid embrace, alongside the corpses of others whose lives have been snuffed out by this demonic caudillo.

Pedro Páramo realized as a child, after his own father was murdered, that you are either “somebody” in that valley, or it is as though you have never existed. If he was to thrive in turbulent times, he had to deny breath and joy to everyone else. We meet his victims: the many women he bedded and abandoned, the sons he scattered like stones in the desert, the priest he corrupted, the rivals he killed and whose land he stole, the revolutionaries and bandits he bought off and manipulated. Of particular significance are a couple, a brother and sister living in incestuous sin, their inability to conceive a child symbolizing the sterility to which Pedro Páramo has condemned Comala. Unlike Telemachus in The Odyssey, Juan is never reunited with his father, only finding the inferno that his father, like a fiendish demiurge, has created and ruined, a world made with such cruelty and mercilessness that there is only room for one person to thrive.

Behind Pedro’s ascendancy there is more than merely greed and a will to power. He has accumulated money and land and henchmen so that he may, like a Satanic Gatsby, some day possess Susana San Juan, the girl he dreamed of when he was a boy with no prospects. But Susana, now a grown woman, has gone mad, and her erotic delusions have carried her beyond Pedro’s reach. The reader, along with the ghosts of the town, have access to her voice, but not the husband who has sold his soul to make her his bride. Nor can Pedro control the destiny of the only other human being he loves: Juan’s half-brother, Miguel Páramo, the spitting image of his progenitor, callous toward men and abusive of women, who is thrown from his horse while jumping over the walls his father erected to protect his land from poachers. Instead of inheriting Pedro’s domains, Miguel joins the souls who wander the earth in search of an absolution that never arrives. Pedro himself is killed by his illegitimate child, Abundio. The novel ends with the death of the despot, who “collapses like a pile of rocks.”

Pedro Páramo is a cautionary tale, one that should resonate in our own era of brutal strongmen and rapacious billionaires. According to the wishful fantasies in Rulfo’s imagination, all the power and wealth that the predators of his day have accumulated cannot save them from the plagues of loneliness and sorrow. Many Latin American authors later emulated Rulfo’s vision of the domineering macho figure who terrorizes and corrupts nations. Faced with the seeming impossibility of changing the destiny of their unfortunate countries, writers at least could vicariously punish the tormentors of their people in what became known as “novels of the dictator.”

What made Rulfo exceptional, a fountainhead for so much literature that was to follow, was his realization that to tell this tale of chaos, devastation, and solitude, traditional narrative forms were insufficient, that it was necessary to shake the foundations of story-telling itself. Though modernity was denied to his characters, isolated from progress by the tyrant of his tale, Rulfo expressed the plight through an aesthetic shaped by the avant-garde art of the first half of the twentieth century. This twisting of categories and structure was indispensable for him to express how a Comala that dreamed of beauty and justice, a place pregnant with hope, could be transformed into a bitter, confusing graveyard. What other way was there to portray the disorder of death? Linear, chronological time does not exist in death, nor in the deranged psyches of those who live as if they had already died. From the perspective of the afterlife, everything is simultaneous, everything has already happened, everything will happen perpetually in the restless minds of the ghosts. Rulfo’s technique of scrambling time and place, this and that voice, his characters’ inner and outer landscapes, imposes on the reader a feeling of helpless anxiety akin to the anomie the specters themselves suffer.

Today, we live in a world where the version of an encounter with the dead that confronts us occurs in a very different form than the one that Rulfo described in his work. Last year’s hit Pixar movie, Coco, celebrated the cultural heritage of the Mexican tradition of El Día de los Muertos with humor and a heartwarming message. In Pedro Páramo, the young man who ventures into the Land of the Dead in search of his origins does not return, as Miguel Rivera does in the Disney film, with a song of optimism and redemption. The purveyors of mass entertainment are certainly aware that most audiences would rather not be fed tales of anguish and despondency. Who can blame moviegoers for preferring happy endings instead of terrifying ghosts murmuring from their tombs that there is no hope?

But life is not a movie, and life always ends in death. Rulfo posed vital questions about the dead and how we can grasp their departure without succumbing to despair. When Latin Americans first read the novel, they were enthralled by it. While each wisp of a scene is presented with the minute implacability of matter-of-fact realism, like a series of images captured by a camera, the cumulative effect is to give a tortured, transcendent, trance-like allegory of a country, of a continent, of the human condition. Such an extraordinary feat of the imagination would be impossible had it not been for Rulfo’s remarkable prose, incantatory yet restrained. Against the grain of the baroque, overwrought style that had seemed to define Latin American literature, each word emerges as if extracted from the soil, leaving readers to apprehend what is held back, to divine the vast unspoken world of extinction, the final silence that awaits us all. Juan Rulfo spoke so eloquently not just for the dead, but for those among us who never really had the chance to live.