Dominique Nabokov—whose images appear regularly in The New York Review—has photographed numerous writers and artists since she began her career in the early 1980s. But in addition to portraiture and reportage, Nabokov has also captured cultural figures by photographing not the people themselves, but their living rooms. Last year, she completed a series of interiors with her most recent book, Berlin Living Rooms (2017), the final installment in a trilogy that began with New York Living Rooms (1998) and continued with Paris Living Rooms (2002). “I approach the living rooms as I approach the people I photograph,” Nabokov has said. “A portrait as close to the reality as possible.”

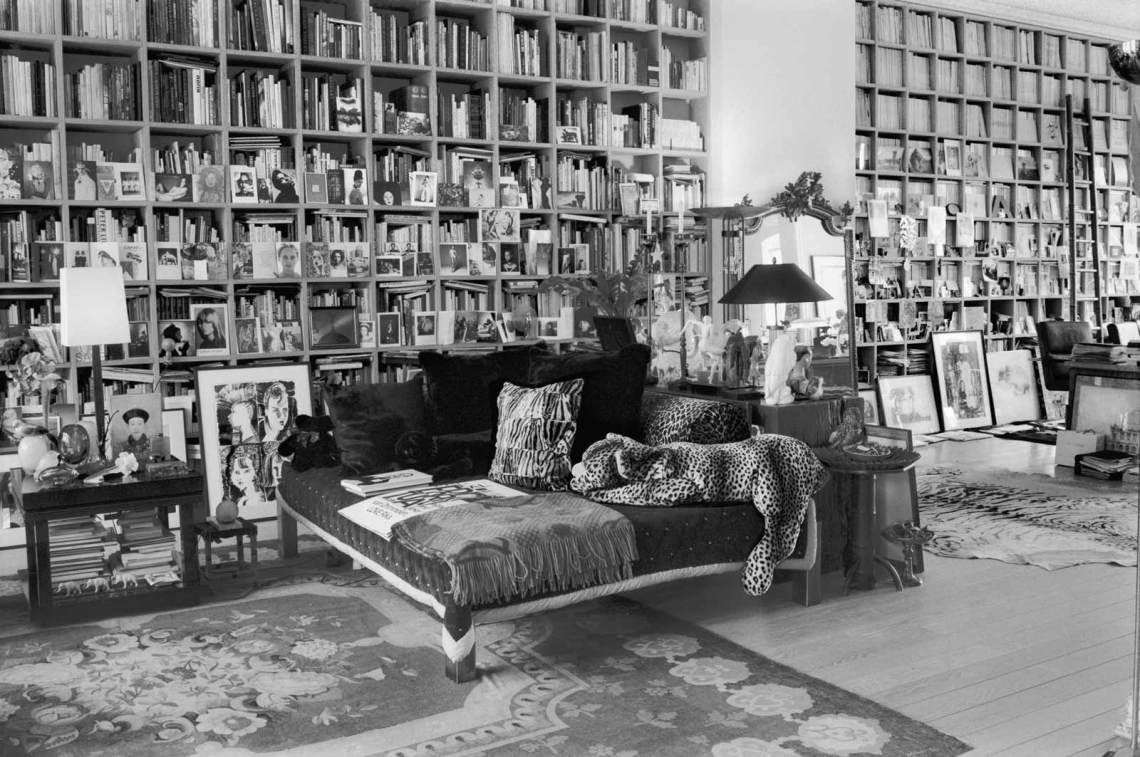

The photographs in Berlin Living Rooms are a delight for those wondering how others—mostly the other half, it seems, but not entirely—live. The light streaking in from the floor-to-ceiling, wall-to-wall windows in Gwen Callec and photographer Michael Shäfer’s Prenzlauer Berg apartment is enviable. Torsten Schröder and Dietmar Schwarz, director of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, have more chairs in their Charlottenburg home than I’ve ever seen in a single living space. Artist Patricia Waller’s balancing penguins, standing next to what looks like an oversized Venus fly trap (could it be real?), are eccentric and stylish. Leopard prints, impressive libraries, and open spaces abound.

Nabokov and I spoke in the conference area of the New York Review office—one might call it the living room of the NYRB, with a comfy couch and Barbara Epstein’s collection of books displayed near large windows that look out onto the West Village. What follows is a condensed and edited version of that conversation.

—Lucy McKeon

Lucy McKeon: Your first Living Rooms project was published in 1998. What initially gave you the idea to photograph people’s living spaces?

Dominique Nabokov: It was a commission from The New Yorker. Originally, it was to do a photo-essay on the writer’s room. And as you know, I’ve been photographing writers for thirty years. I was bored, in a way, with the idea. So I said I would prefer to photograph another space. And maybe I said, “I would prefer to do the bedroom—and not only of writers but of people from different parts of the cultural world.” Crary Pullen, the photo editor at The New Yorker, and David Kuhn, then creative director, were the originators of the project and told Tina Brown, who agreed. Apparently, she said, “Why the bedroom? They’re not going to let you come in!” So we settled on the living room.

You write in your introduction to Berlin Living Rooms that you see photographs of living rooms as portraits of people’s interiors—both literally and as visual representations of who they are.

Yes, the living room is ultimately the vitrine, your vitrine, to the world. It’s where you want to show yourself to the world, consciously or unconsciously. And even if you use an interior decorator, it still will betray who you are. So, in a way, it’s like your clothes. It betrays who you are—not 100 percent, of course, but 75 percent.

And are there artistic antecedents, either painters or photographers of domestic scenes that you had in mind who have inspired your approach?

Oh, no. I tell you, it is very banal. When I was very young, around ten or eleven years old, I went to the movies often. I mostly saw American movies. I was a fan of the movie stars of the time, and I bought every magazine I could. I collected magazines, even American magazines—in Paris, you could find Modern Screen, Photoplay, Motion Picture, Screen Play, but also Life magazine, Look, Paris Match, etc.—and you could see how the movie stars lived, and I really liked that. I liked to see how it was in Hollywood, the living room, the garden, the swimming pool. I guess I was already a voyeur! So that started, in a way, my idea of becoming a photographer. It was a way to enter a world that I couldn’t enter because I lived in a provincial town in France [in Compiègne, north of Paris].

Even in the magazines at the end of the Fifties and the Sixties, they show you a spread of their life, you enter their life, and they were very gorgeous photos, too. I had a collection of about maybe two, three thousand magazines. And my aunt (I was brought up in the country by my aunt and uncle), one day she had enough. They took up too much room—I was gone, I had my own life—so she threw them all away. And I adored her, but never forgave her for that.

Darryl Pinckney says in his essay that appears in Berlin Living Rooms, “The living room is the most public of spaces in a private home. It retains its atmosphere of formal reception.”

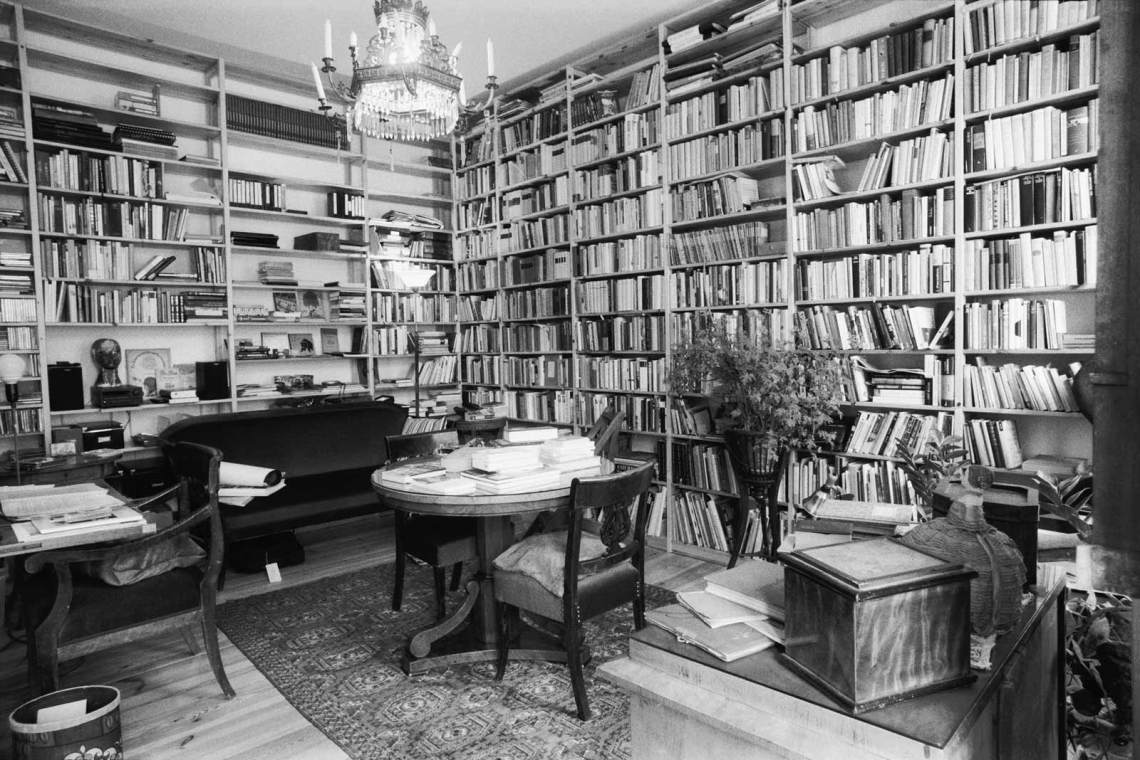

On the higher level of society in America, you could see that. In New York Living Rooms, some of [the people whose living rooms I photographed] have a lot of art. The rest, on the interiors of musicians, writers, poets, like Joseph Brodsky, Jerome Robbins, Barbara Epstein, Elizabeth Hardwick, Allen Ginsberg, Susan Sontag—are more modest. In France, the bourgeoisie are conventional in a certain way: but they’re also a bit nervous to show their art in photographs because it is a small country and they’re afraid of the tax people.

In Berlin, you don’t necessarily have the feeling that these people are living in their places. There are a few personal living rooms, like the one of Jenny Erpenbeck. She comes from an East Berlin family, and she told me that the furniture in her living room was her grandmother’s. Basically, Berlin is full of foreigners and transplants. It’s a city that is being rebuilt, because it was partly destroyed during World War II. So you have a lot of artists, young people, intellectuals, coming from all over the world. So, maybe, I think their personal environment is a bit impersonal, and I think that the Germans of today are very cautious about the way they’re seen by the outside world. What is your feeling?

I thought, compared to the other books, the images in Berlin Living Rooms felt spacious—and this was confirmed by both Darryl’s essay and the afterword by ZEITmagazin editor Christoph Amend. They both remark upon the open spaces.

Yes, which is true! What is left of Berlin is no longer an industrial or business place, it’s basically a political capital and a place where artists lived. And it’s a place in-between. The rents were cheap, and although they are increasing, they are still very cheap comparatively to New York, London, or Paris. There you see some people who are living quite modestly—even famous artists, who have moved there because they can set up their studios in factories.

Very different from New York.

Yes, in New York, a kitchen is a closet.

So how did you choose your subjects? Did you have any particular aim for variety in mind?

Now, for New York Living Rooms, among the first eighteen published in The New Yorker, I had arranged a few, like Joseph Brodsky, Susan Sontag—I did because I knew them. But maybe they also accepted in part because it was The New Yorker, you see? I knew a lot of people in New York really, so you could say that 75 percent of the book was my taste. But I didn’t get everybody I wanted.

Who didn’t you get?

Well, I’ll tell you: the three people I didn’t get and I wanted to have, they are linked to the publishing world… Tina Brown: she said no. Anna Wintour said no. And photographers Annie Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, and Irving Penn said no.

Ah, that makes sense.

Voilà. Well, but no, it doesn’t make sense! You know, it’s unfair. They are part of the publishing world, so I think they don’t respect the rules of the game.

How unfair.

But we must respect it. I never pushed when people said no. I didn’t want somebody who really didn’t want to do it. Because it’s true that photography is an intrusion into your life.

Actually, that’s a perfect segue. With portraits of people, photographers often have to work to put their sitters at ease or to win their cooperation. But I was wondering, with these “portraits without people,” what do you have to do with the people who live in these spaces? What are your interactions with them, what instructions do you give them, and what concerns or anxieties do you encounter?

Well, there were no instructions. The only thing I said to reassure them—and also because that’s the way I work—I said, “I come with a tripod, a camera, I don’t bring any lighting material.” I didn’t want to annoy people, arriving with enormous equipment, which I never use. I use the light of their apartment, and I’m very quick. I know that photography, in a certain way, is an imposition. The maximum it would take to photograph the living room would be two hours. Very often when I came, they were not there. If they were well-off, they had a maid or butler. In New York, Julian Schnabel was there and he was extremely nice to me. And the Clementes, too, I forgot they were there they were so unobtrusive. Louise Bourgeois was sitting at her table watching over me like a bird of prey. Many of the artists were there, but they were cool, and rather happy to have me.

Advertisement

In Paris, that was the same. In Paris, I also knew a lot of people. Some gave me instructions. Pierre Bergé, in New York, and Yves Saint Laurent, let me photograph their apartment at the Pierre Hotel. They did not care that much, it was the New York vitrine so I could do what I wanted. In Paris, on the other hand, Pierre Bergé made me photograph the corner of his living room where he has that famous painting of Ensor, and which became the cover of the book. Yves Saint Laurent let me photograph his living room full of masterpieces while he wasn’t there. And otherwise, people let me do what I wanted. Also, if by chance they were there, you know, with the Polaroid, you have a result right away.

What Polaroid were you using?

For New York and Paris, I used a very special Polaroid that doesn’t exist anymore: Polaroid Colorgraph type 691 film. We could see the result right away. Now, for Berlin, I could not use it because it does not exist anymore, and I saw Berlin mostly in black-and-white anyway.

Yes, I wanted to ask about that. You used Ilford black-and-white film for Berlin?

Yes, because this time I used my reflex camera, an Olympus OM-1. I have four of them and I’ve done all my career work with them, except sometimes I use a Leica M3. But for this project, I only used my Olympuses.

Can you describe a bit more how you see Berlin in black-and-white?

I lived in Berlin a lot of the Seventies and the Eighties at the time of the Wall, and Berlin was linked to the news, to the history, to documentary. It was not a dark city but it was a—how should I say?—a city that you couldn’t see in color. I saw it through a lot of the films that I loved of the Thirties and Forties, Billy Wilder or [G.W.] Pabst, [Josef von] Sternberg, and all these people, the Expressionist period, and also the photographer Erich Salomon. I still see Berlin this way. I’ve done some color pictures of Berlin, but the colors of Berlin are greenish, yellowish, quite special, but I was not inspired by them.

And how did you choose your subjects for Berlin?

The same way. But of course, Berlin had changed, so most of the people I knew were dead or gone. At the time [that I lived there], my husband was the director of the Berlin Music Festival; there were a lot of musicians, writers, painters, curators, and heads of museums who are not there anymore. But I chose people in the same worlds. I had a fellowship from the American Academy of Berlin. They helped me a lot. I’d say that 50 percent of the book was done when I was at the Academy in 2014. I met by chance the granddaughter of a friend of Nicolas’s [my husband] and mine, Josephine Hubalek. She has a beautiful apartment in Charlottenburg next to the Kempinski Hotel. She said, “When you come back to Berlin you should stay with me.” So when I came back in 2016 and 2017, I stayed with her.

She knew a world that I didn’t. A lot of aristocrats had moved back to Berlin to buy apartments. And each person sent me to other people, you see. I wanted a sort of a balance. I live in the world of the arts. I’m also interested in politics, of course. I got Mayor Koch of New York, but I couldn’t get the Mayor of Paris. He refused. I would have loved to have had Mrs. Merkel, but I knew nobody who knew her. She may have agreed, actually. I should have pushed, but I didn’t.

Do you have a favorite living room, in the book?

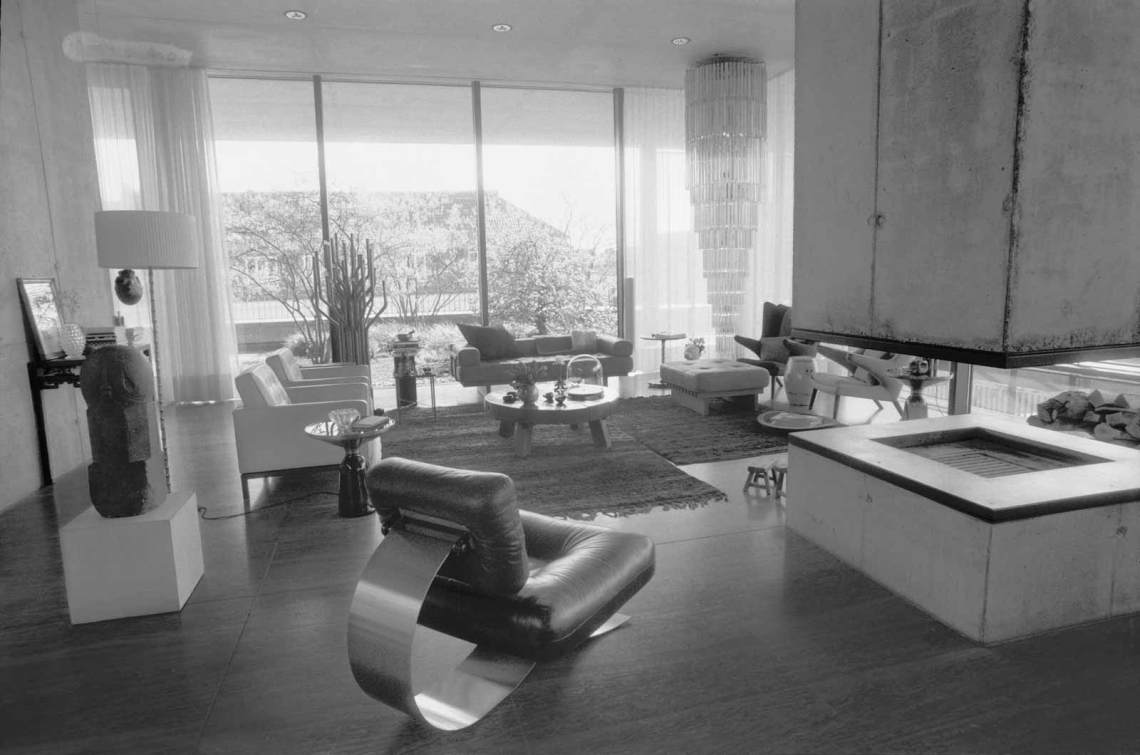

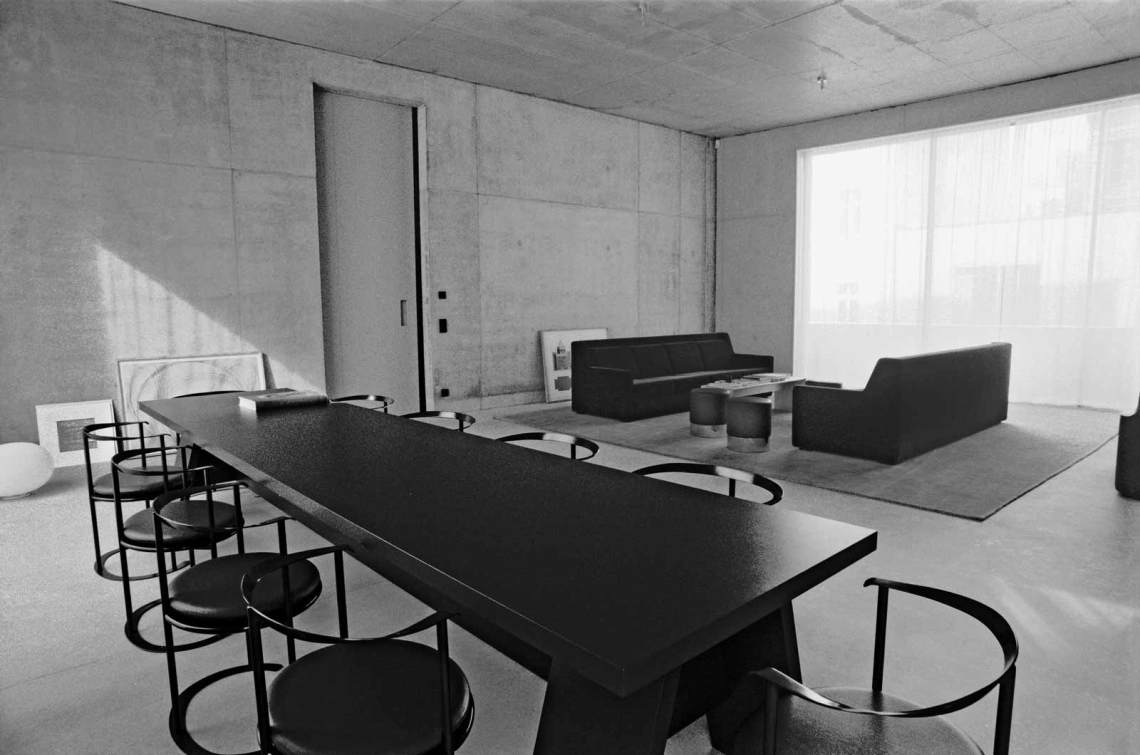

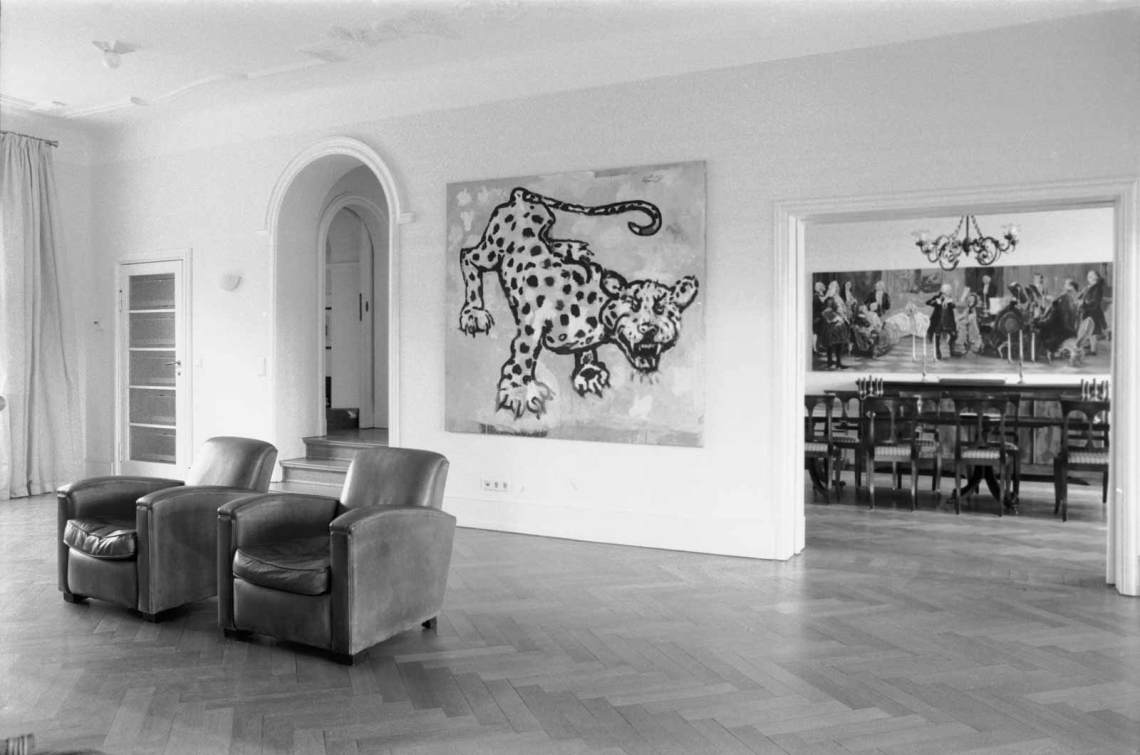

Well, as a picture, I like this one [Dr. Evelyn Stern and Sir David Chipperfield, architect, Mitte]. But I don’t know if I would like to live there. Let me see if I have a favorite one… this one [Karen Lohmann, art historian, and Christian Boros, art collector, German advertising maestro, Mitte] is quite extraordinary because it is the top of a bunker that the Nazis built in the middle of Berlin. They have a huge, huge art collection. But I don’t know if I would like to live there, either.

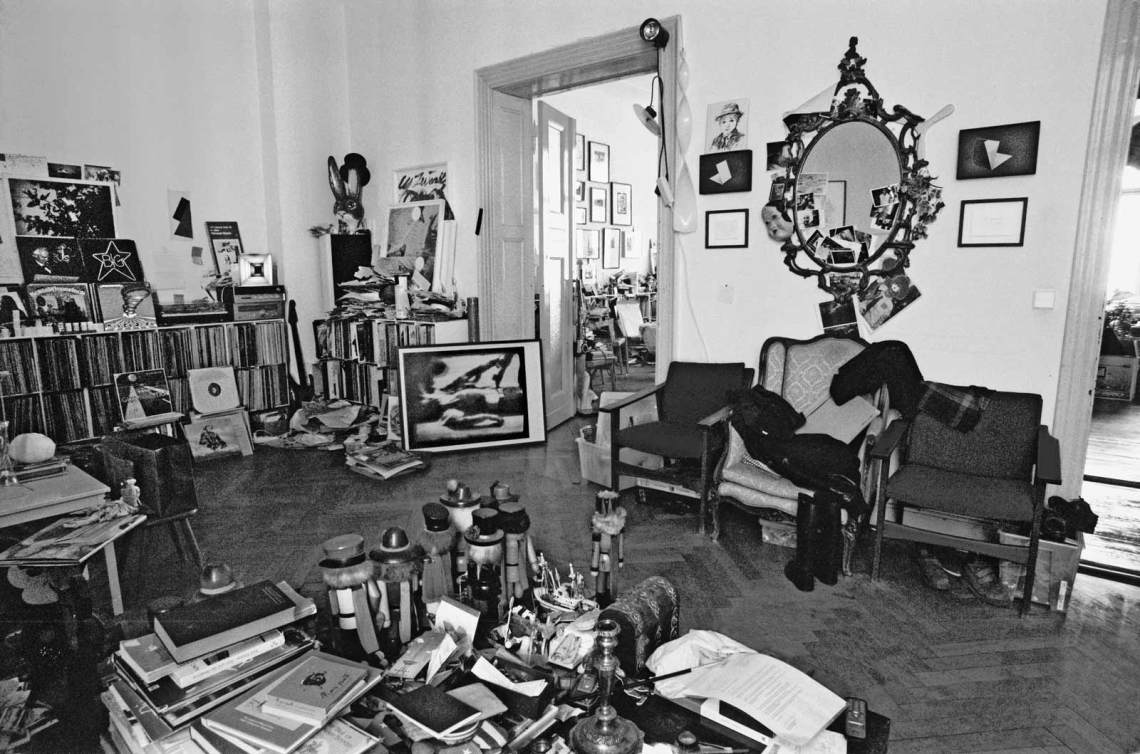

This is the studio of the famous model, Veruschka [von Lehndorff], you know, from the movie Blow-Up? She comes from a Prussian family that has an estate not far from Berlin, and she moved back there from New York. And now she’s very different—she’s an artist and she lives in a popular neighborhood [in Friedrichshain].

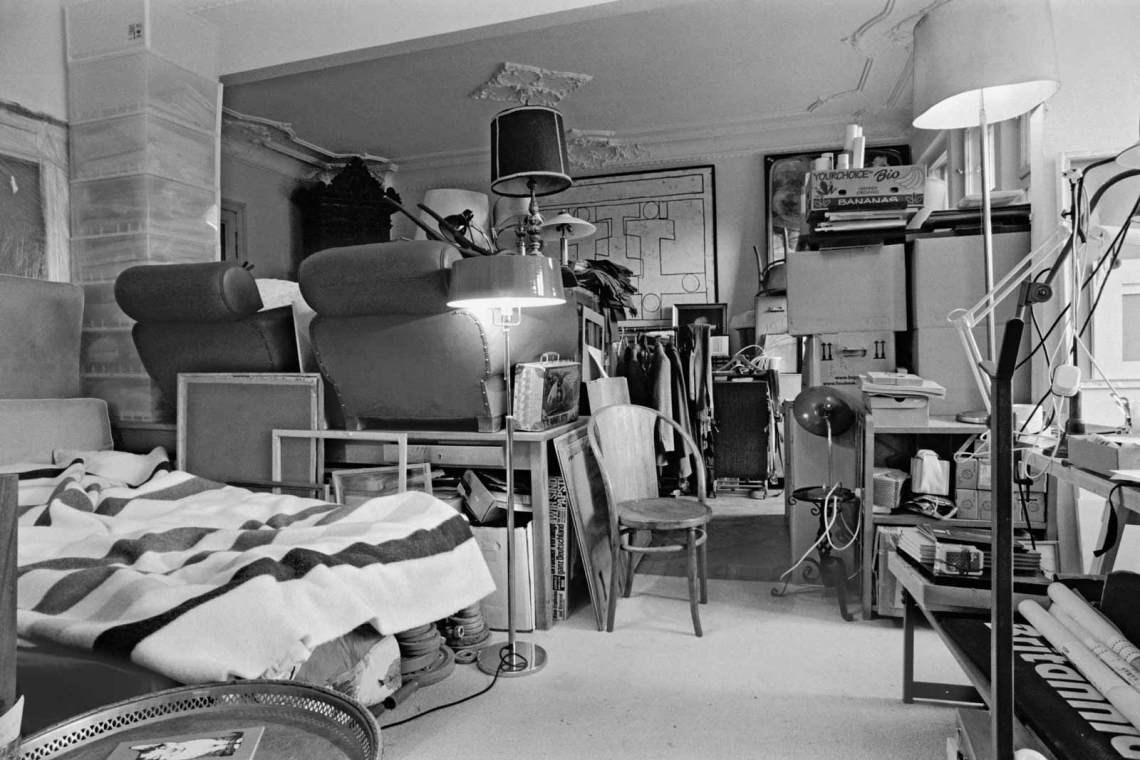

Then there is the apartment of my friend Josephine Hubalek. I adore that apartment. She is an artist, it’s a huge apartment, up there is a kitchen, but in the back there is another room with a huge studio, huge garden, and on the top, a bedroom where I used to stay. It’s a perfect location, in Charlottenburg.

The last image in the book is your own room, the studio that you had at the Academy.

I include my apartment in all the books. Because I thought if I go into people’s houses, and they open their door, why shouldn’t I open my door, too? I respect the rules of the game.

Berlin Living Rooms is published by Apartamento. Saturday, March 3, Dominique Nabokov will be discussing the book at Albertine in New York City.