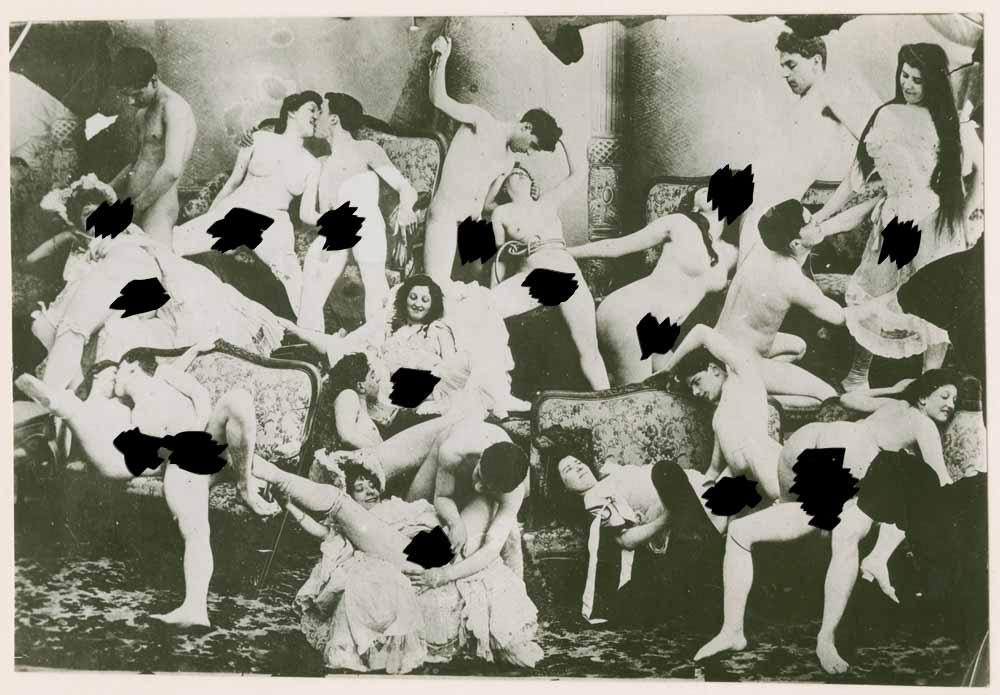

The Kinsey Institute A photograph from the Kinsey Institute archives (censored by the Review editors), 1895–1900

In 2000, an Indiana politician attacked his opponent, John Frenz, by assailing the Kinsey Institute, founded more than fifty years earlier within Indiana University. “The Kinsey Institute is the largest library of pornography of its kind in the world,” his attack ad proclaimed, elaborating that its “library contains sex-related art, studies on bestiality, obscene photographs of children,” and that the institute supported “homosexuality as an accepted lifestyle.” This politician, a strong-values conservative named Eric Holcomb, is now the governor of Indiana. What terrible infraction had Holcomb’s opponent committed? He’d voted for a state budget, of which a tiny portion funded the Kinsey Institute.

Alfred Kinsey began his career as a biologist, with a focus on entomology and an expertise on the gall wasp. He didn’t switch to studying sex until he taught a course on “Marriage and Family” at Indiana University, and found that there was a dearth of scientific literature on sex. He began collecting information about the sexual histories of students in his courses, and amassed a large quantity of them. When the University’s president, Herman Wells, made Kinsey decide between continuing his sex research and teaching the course, he chose the former. In 1947, with the help of a lawyer, Kinsey founded the Institute of Sex Research “to continue research on human sexual behavior,” as well as to secure a library for his growing collection of books and artifacts, according to James Capshew’s Herman B. Wells: The Promise of the American University. The institute was created as a “separate entity that could be firewalled from local, political, and institutional mandates,” Judith Allen and her co-authors write in the recently published The Kinsey Institute: The First Seventy Years.

Since 1947, the institute’s core mission has been to study subjects that no other academic institution would touch: sex in all its permutations. According to its official history, it was founded to encourage “the right to study sex and to proclaim that study openly.” Kinsey published two essential works on human sexuality based on his surveys—Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953)—that both became New York Times bestsellers and scandalized polite society with their revelations. Kinsey discovered that over a third of men had had sexual experiences with other men, a shocking discovery at a time when same-sex sexual activity was illegal and widely considered immoral. He also found that women were more likely to have orgasms from masturbation than from heterosexual intercourse, and that half of the female population had had sex before marriage. Over 50 percent of the people he surveyed reported having an erotic response to biting. Kinsey’s groundbreaking work legitimized sex research and paved the way for Masters and Johnson’s studies in the mid-1960s, which proved, through laboratory research on copulating and masturbating subjects, that women could have multiple orgasms, and that orgasms during masturbation were typically more pleasurable than those during intercourse.

During the decades after Kinsey’s death in 1956, the institute expanded his agenda—opening a sex clinic, hiring an art curator, starting public tours, and releasing a sex-reporting app. But over the past three years, it has quietly become a shell of its former self. As its new director Sue Carter told the Indianapolis Star in 2016, “Where once research into sex, gender and reproduction formed the backbone of the institute’s work, now love, sexuality and well-being will take center stage.” Its name has been shortened to “The Kinsey Institute.”

In many ways, Carter was an unusual choice to lead the institute. Although she is the first biologist to head up the institute since Kinsey himself, her career has focused on rodents—in particular, on the prairie vole, one of the few mammals that pair-bonds and is monogamous. Carter previously built a research lab at the University of Illinois-Chicago where she discovered that oxytocin—the so-called love hormone—played an essential part in promoting pair-bonding in prairie voles. Almost none of Carter’s hundreds of published scientific papers relate to human sexuality, and few of her articles have appeared in sex-research journals. This has baffled sex researchers at many other institutions. “The overarching kind of focus behind the institute was to look at sex research, not at research on love and not at research on intimacy,” said Cynthia Graham, a professor in sexual and reproductive health at the University of Southampton, who is also a Kinsey Institute fellow and editor of The Journal of Sex Research.

Perhaps tellingly, Carter’s own research on vole monogamy has been cited by pro-abstinence and anti-pornography organizations to justify their positions. Physicians for Life, a pro-life association based in Alabama that also advocates for abstinence, uses Carter’s research to argue that monogamy is natural and built into our biology. They claim that sex out of wedlock will lead to a release of oxytocin that produces an expectation of commitment which is then disappointed, leading to “depression, dissatisfaction, and the disruption of future bonding potential.” Meanwhile, a website called Your Brain On Porn uses Carter’s oxytocin research to argue that strong pair bonds make us less likely to pursue addictive behaviors like porn-watching. Another anti-porn advocate uses Carter’s research to make a diametrically opposed argument: that oxytocin “bonds” men to porn and away from human partners.

Advertisement

Since Carter took up her position at the institute, she has hired five former students or colleagues from her lab at the University of Illinois-Chicago; none of them do sex research. She’s also hired her husband, the psychologist Stephen Porges, as a “distinguished university scientist.” Porges had never written an article on sex research when he was hired, aside from one that he co-authored with his wife on sexual receptivity in hamsters. According to the Kinsey Institute’s website, over the three years that Carter has been the director, only about 40 percent of the publications coming out of the Kinsey institute have been related to human sexuality, compared to about 88 percent under the last two directors. Many of the reports produced under Carter’s leadership seem to be focused on the effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on everything from “aggression in domestic dogs” to schizophrenia in middle-aged women. Other studies are concerned with non-sex related psychological disorders like depression and anxiety.

Perhaps the most visible change at the institute under Carter has been to its art collection, which had, since the 1990s, been displayed in the affiliated gallery. The collections are extensive and include such rare pieces as Ian Hornak’s painting of nudes adorned with animal heads, Herb Ritts’s photographs of male nudes, and erotic works by Marc Chagall and Picasso. Public shows at the gallery ended in 2015. In addition to shuttering the gallery, Carter terminated the institute’s popular Juried Erotic Art Show, which had run for a decade. This event not only attracted large crowds, but also provided more artwork to the institute, as many of the pieces were donated.

All of the changes at Kinsey have occurred at a time when the political climate in Indiana has become increasingly proscriptive toward any form of sexual expression other than heterosexual sex within marriage. When Carter was hired, the governor of Indiana was Mike Pence (now vice president of the United States), who signed one of the most extreme anti-abortion state laws in US history and cut funding to Planned Parenthood. And about six months before she was hired, conservative critics of Kinsey had been particularly outspoken after the institute sought, and was granted, consultative status as a nongovernmental organization with the United Nations. In May 2014, Kinsey’s greatest nemesis, conservative activist Judith Reisman, founded an organization called Stop the Kinsey Institute, encouraging people to sign a petition that would revoke the institute’s newly won UN accreditation. Since the 1980s, Reisman had been arguing that Kinsey’s research was inaccurate, involved the sexual abuse of children, and was responsible for the “moral decay of millions of people.”

In the years since Carter was hired, the Kinsey Institute has become increasingly dependent on the support of the university and, as a consequence, the conservative state government. Kinsey initially set up the institute as an independent nonprofit organization associated with Indiana University, in an attempt to protect it from political pressure; thanks to its nonprofit status, the management of the institute was answerable only to an independent board of directors. But in December 2016, the institute merged with Indiana University, and now answers only to the university’s administration.

Many of the people I interviewed believe that the university saw the institute as a political liability, with the potential to compromise the university’s own access to state funding, and so, instead of getting rid of the institute, they made its focus less controversial. The fear of defunding has only become more grounded since Eric Holcomb—whose attack ad in 2000 said that “tax-payers should NOT be forced to support Kinsey”—replaced Pence as governor last year. Holcomb now signs off on the budget that supports the institute.

“There is a reason that I was selected and not someone from the more traditional sex-research field,” Carter told me, somewhat cryptically, after I asked her if she thought the organization of the institute had changed. She didn’t elaborate on what she meant, but instead went on to say that “Kinsey has to have some kinds of priorities to survive in the future. We cannot focus simply on things like sexual pleasure. We can’t because there’s no funding for it.”

Advertisement

Why did the institute merge with the university? Nearly everyone involved to whom I spoke cited a different reason. According to Amy Applegate, the chair of Kinsey’s board at the time, the merger extended protections of academic freedom to Kinsey while also giving the institute access to all the university’s resources. For her part, Carter said that the institute needed more financial support. Fred Cate, Indiana University’s vice president of research, cited both finances and integration with the library. Rick Van Kooten, the vice provost of research, said that institute could now enjoy stronger protections against legal challenges like the one in the 1950s, when the US Customs Office intercepted a box of erotic goods from overseas bound for Kinsey on the grounds that it was obscene. But even though the institute was an independent nonprofit at the time, it still managed to acquire the university’s help and prevail in its ensuing legal battle against the Customs Office. Jorge José, a former university administrator, said the merger was intended to give the university’s administration more “oversight over the whole operation of the Kinsey Institute.”

Whatever the actual reasons behind it—political, practical, or otherwise—the institute’s incorporation with the university has only compounded the effects of Sue Carter’s tenure, in making the institute less public, and less about sex. Perhaps the saddest part of the Kinsey Institute’s change in focus is that our country needs it now more than ever. The Kinsey Institute should be participating in the national conversation on sexual assault and harassment. The institute should be leading the way with discussions on the importance of female sexual pleasure, the “orgasm gap” between men and women, and the fact that so many women experience pain during sex. In the words of Edward Laumann, who has researched human sexuality at the University of Chicago for over forty years, the institute “is about human sexuality, so why the hell are we talking about voles, however interesting that may be?”